Don’t Tamper With Symbols! / Ne faussez pas les symboles!

Don’t Tamper With Symbols!

In 1969 I did the research and wrote the catalogue for an exhibition of 153 items entitled Heraldry in Canada/ L’art héraldique au Canada and mounted by the Public Archives of Canada. It was opened during the annual general meeting of the Heraldry Society of Canada. The event having been reported in all the local newspapers, I received a call from Colonel Archer Fortescue Duguid, a historian who had made several important contributions to Canadian Heraldry (see his biography in The “Who was who” of Canadian Heraldry on this site: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/d.html). When he appeared before the flag committees in 1945 and 1964, he was able to sum up complex questions in the clear concise manner of a person with a long experience in the field. On the other hand, he could become quite curt if misunderstood or not taken seriously (see Matheson, Canada’s Flag, p. 107).

He had telephoned because he was highly annoyed with an account by Sheila McCook entitled “Heraldic art depicts historic tale” which appeared in The Ottawa Citizen on November 10. The author had confused a horse with a unicorn (basically a horse with appendices from four other animals, see: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/the-unicorn-in-canada.html). Duguid also objected to several other minor things. I have reread the article, and apart from the horse-unicorn confusion, it was well done for the general public (the intended audience), though an expert could quibble some generalizations. During the conversation (mostly one way), I got the impression that Mr. Duguid was trying to impress upon me that he was the master of the field, and that I had no business meddling with something I knew nothing about. Actually he had no business blaming me for what someone else had written. I simply had to tell him to complain to the newspaper itself, but being young and inexperienced in such matters, I did not defend myself very well. This was probably a good thing because the matter did not seem to go any further, and it is not a good idea for a public servant to invite outside criticism whether warranted or not.

The second bout of criticism came as a result of another exhibition mounted by the Canadian Museum of Civilization for the 25th anniversary of Canada’s flag in 1990, a project Ralph Spence, Alistair Fraser and I worked on with the staff of the museum, myself as a guest curator on loan from the National Archives of Canada.

Publicity in The Ottawa Citizen announced that one of the aims of the exhibition was to “relive the post-Confederation struggle for independence.” This phrase was very badly chosen. After Confederation, Canada had gained its independence in a gradual manner, without any strong opposition from England. Although the help of British troops was sought during the Red River and North-West Rebellions, these two uprisings were not primarily directed against England, but against Canada who had purchased the territory (Rupert's Land) from the Hudson’s Bay Company on 20 March 1869.

Eugene Forsey, a former senator and renowned constitutional expert, pounced on the statement as being an effort to Americanize Canadian history and vented his indignation in a letter to The Ottawa Citizen dated January 3 (doc. 1). His sarcasms were powerful, although completely irrelevant to the actual content of the exhibition. I responded to Mr. Forsey in a letter to The Ottawa Citizen dated January 10 in which I retorted that the exhibition related largely to European heritage and had nothing to do with the United States (doc. 2). On 11 February 1990, he wrote me saying that he has no doubt been misled by the advertisement but could not understand how there could be “vintage photographs, rare documents and an overwhelming selection of flags” on display as the original advertisement had claimed. He inquired “How many flags have we had?” He was also mystified as to what “The Maple Leaf Forever New” could possibly mean.

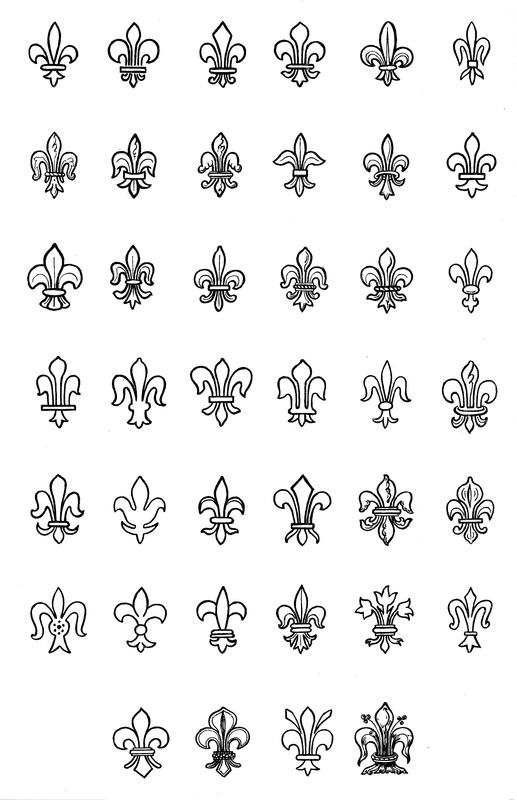

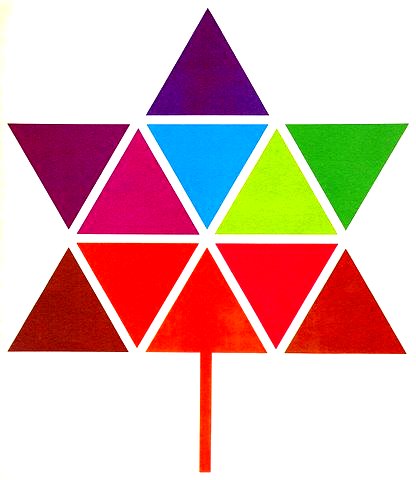

Actually the attempts to give Canada a distinctive flag had begun within a few years after Confederation. Over the years, there were thousands of proposals for a Canadian flag and, for close to a century, the Union Flag (Jack) rivaled with many Canadian versions of the Red Ensign as the national flag of the country (see: http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/flag-of-canada/, and fig. 1). The National Archives of Canada holds metres of documentation relating to these flags. As for the title, The Maple Leaf Forever New / Vive la feuille d’érable, it was inspired by Alexander Muir’s “The Maple Leaf Forever” with “new” added because strong symbols keep renewing themselves in design and often in meaning. This is true of the fleur-de-lis (fig. 2) and it is likewise true of the maple leaf. The leaf as it appeared on the Canadian flag in 1965 had never been seen before. Two years later, a revised depiction of the maple leaf was adopted for Canada’s Centennial (fig. 3). Air Canada has used two different styles of leaves since 1968, and dozens of interesting variances in design can be found on the internet. By adding “new” to the title, I also wanted to convey a message that was a little enigmatic, that aroused curiosity.

It is easy to forget the extent to which the flag of Canada is rooted in history. To become the main element on the national flag, the maple leaf, which was accepted as a symbol of Canada early in the nineteenth century, had to triumph over its rival the beaver which was a symbol of the country from the seventeenth century (see: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/chapter-2-the-beaver-and-maple-leaf.html). It had to supplant colonial symbols such as the fleurs-de-lis, the lions of England and the Union Jack which had also been in North America for centuries.

Mr. Forsey accepted my explanations, but it is ironic that, in both of the cases described here, the criticisms did not relate to the content of the exhibition. The complaints reacted to information in the press, and the complainers were unable to visit the exhibition they complained about.

In 1969 I did the research and wrote the catalogue for an exhibition of 153 items entitled Heraldry in Canada/ L’art héraldique au Canada and mounted by the Public Archives of Canada. It was opened during the annual general meeting of the Heraldry Society of Canada. The event having been reported in all the local newspapers, I received a call from Colonel Archer Fortescue Duguid, a historian who had made several important contributions to Canadian Heraldry (see his biography in The “Who was who” of Canadian Heraldry on this site: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/d.html). When he appeared before the flag committees in 1945 and 1964, he was able to sum up complex questions in the clear concise manner of a person with a long experience in the field. On the other hand, he could become quite curt if misunderstood or not taken seriously (see Matheson, Canada’s Flag, p. 107).

He had telephoned because he was highly annoyed with an account by Sheila McCook entitled “Heraldic art depicts historic tale” which appeared in The Ottawa Citizen on November 10. The author had confused a horse with a unicorn (basically a horse with appendices from four other animals, see: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/the-unicorn-in-canada.html). Duguid also objected to several other minor things. I have reread the article, and apart from the horse-unicorn confusion, it was well done for the general public (the intended audience), though an expert could quibble some generalizations. During the conversation (mostly one way), I got the impression that Mr. Duguid was trying to impress upon me that he was the master of the field, and that I had no business meddling with something I knew nothing about. Actually he had no business blaming me for what someone else had written. I simply had to tell him to complain to the newspaper itself, but being young and inexperienced in such matters, I did not defend myself very well. This was probably a good thing because the matter did not seem to go any further, and it is not a good idea for a public servant to invite outside criticism whether warranted or not.

The second bout of criticism came as a result of another exhibition mounted by the Canadian Museum of Civilization for the 25th anniversary of Canada’s flag in 1990, a project Ralph Spence, Alistair Fraser and I worked on with the staff of the museum, myself as a guest curator on loan from the National Archives of Canada.

Publicity in The Ottawa Citizen announced that one of the aims of the exhibition was to “relive the post-Confederation struggle for independence.” This phrase was very badly chosen. After Confederation, Canada had gained its independence in a gradual manner, without any strong opposition from England. Although the help of British troops was sought during the Red River and North-West Rebellions, these two uprisings were not primarily directed against England, but against Canada who had purchased the territory (Rupert's Land) from the Hudson’s Bay Company on 20 March 1869.

Eugene Forsey, a former senator and renowned constitutional expert, pounced on the statement as being an effort to Americanize Canadian history and vented his indignation in a letter to The Ottawa Citizen dated January 3 (doc. 1). His sarcasms were powerful, although completely irrelevant to the actual content of the exhibition. I responded to Mr. Forsey in a letter to The Ottawa Citizen dated January 10 in which I retorted that the exhibition related largely to European heritage and had nothing to do with the United States (doc. 2). On 11 February 1990, he wrote me saying that he has no doubt been misled by the advertisement but could not understand how there could be “vintage photographs, rare documents and an overwhelming selection of flags” on display as the original advertisement had claimed. He inquired “How many flags have we had?” He was also mystified as to what “The Maple Leaf Forever New” could possibly mean.

Actually the attempts to give Canada a distinctive flag had begun within a few years after Confederation. Over the years, there were thousands of proposals for a Canadian flag and, for close to a century, the Union Flag (Jack) rivaled with many Canadian versions of the Red Ensign as the national flag of the country (see: http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/flag-of-canada/, and fig. 1). The National Archives of Canada holds metres of documentation relating to these flags. As for the title, The Maple Leaf Forever New / Vive la feuille d’érable, it was inspired by Alexander Muir’s “The Maple Leaf Forever” with “new” added because strong symbols keep renewing themselves in design and often in meaning. This is true of the fleur-de-lis (fig. 2) and it is likewise true of the maple leaf. The leaf as it appeared on the Canadian flag in 1965 had never been seen before. Two years later, a revised depiction of the maple leaf was adopted for Canada’s Centennial (fig. 3). Air Canada has used two different styles of leaves since 1968, and dozens of interesting variances in design can be found on the internet. By adding “new” to the title, I also wanted to convey a message that was a little enigmatic, that aroused curiosity.

It is easy to forget the extent to which the flag of Canada is rooted in history. To become the main element on the national flag, the maple leaf, which was accepted as a symbol of Canada early in the nineteenth century, had to triumph over its rival the beaver which was a symbol of the country from the seventeenth century (see: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/chapter-2-the-beaver-and-maple-leaf.html). It had to supplant colonial symbols such as the fleurs-de-lis, the lions of England and the Union Jack which had also been in North America for centuries.

Mr. Forsey accepted my explanations, but it is ironic that, in both of the cases described here, the criticisms did not relate to the content of the exhibition. The complaints reacted to information in the press, and the complainers were unable to visit the exhibition they complained about.

Doc. 1. Letter from Eugene Forsey to The Ottawa Citizen, 3 January 1990.

Doc. 1. Lettre d’Eugene Forsey à The Ottawa Citizen, 3 janvier 1990.

Doc. 2. Letter from Auguste Vachon to The Ottawa Citizen, 10 January 1990.

Doc. 2. Lettre d’Auguste Vachon à The Ottawa Citizen, 10 janvier 1990.

Fig. 1. For close to a century after Confederation, the Canadian Red Ensign rivaled with the Union Jack as the national emblem of Canada. The hand on the left is of a lady, possibly that of Queen Victoria. Postcard no. 456 of the “National Series,” c. 1900. From the Auguste and Paula Vachon heraldic postcard collection.

Fig. 1. Pendant près d’un siècle après la Confédération, le Red Ensign canadien rivalisait avec le Union Jack (drapeau de l’Union) comme emblème national du Canada. La main à gauche est d’une dame, peut-être de la reine Victoria. Carte postale no 456 de la « National Series », vers 1900. Provient de la collection de cartes postales héraldiques d’Auguste et Paula Vachon.

Fig. 2. Thirty-nine different ways of representing the fleur-de-lis. From Arthur Charles Fox-Davies, The Art of Heraldry, 1904, p. 202.

Fig. 2. Trente-neuf façons de représenter la fleur de lis. Planche tirée d’Arthur Charles Fox-Davies, The Art of Heraldry, 1904, p. 202.

Fig. 3. The Centennial symbol of 1967, a stylised maple leaf made up of 11 triangles, ten representing the provinces and the top one alluding to the great Canadian North.

Fig. 3. L’emblème du centenaire de la Confédération, une feuille d’érable stylisée dont dix triangles représentent les provinces et celui au sommet le Grand Nord canadien.

Ne faussez pas les symboles!

En 1969, j’avais effectué les recherches et rédigé le catalogue d’une exposition intitulée Heraldry in Canada/L’art héraldique au Canada, réunissant 153 pièces, montée par les Archives publiques du Canada et ouverte lors de la réunion annuelle de la Société héraldique du Canada. Tous les journaux de la région avaient rapporté l’événement. L’un des comptes rendus, généralement bien fait, confondait la licorne mythique avec un cheval et contenait quelques imprécisions qui pouvaient déranger ceux qui cherchent la petite bête. Je reçus à cet effet, un appel téléphonique du colonel Archer Fortescue Duguid, un historien qui avait conçu quelques insignes et drapeaux militaires et avait contribué à donner au drapeau du Canada les émaux blanc et rouge en insistant que celles-ci étaient les couleurs nationales telles que consignées dans les armoiries du Canada.

Sans avoir vu l’exposition, Duguid me reprochait toutes les erreurs qu’il avait cru repérer dans le journal. Il me faisait sentir qu’il était l’expert incontesté en la matière et qu’un blanc-bec comme moi était mal venu d’envahir sa chasse gardée. Étant jeune et inaccoutumé à ce genre de critiques, je me défendis très mal. Mais ceci était sans doute salutaire, car il avait vidé son sac et il ne semble pas avoir poussé plus avant son opprobre.

Une deuxième volée de critiques concernait une exposition intitulée The Maple Leaf Forever New / Vive la feuille d’érable, montée en 1990 par le Musée canadiens des civilisations pour célébrer le 25e anniversaire de l’unifolié. Une annonce publicitaire parue dans The Ottawa Citizen donnait à l’exposition le thème de « lutte pour l’indépendance après la Confédération ». Ces mots pouvaient choquer, car si le Canada avait connu quelques rébellions, il avait acquis son indépendance progressivement sans recours aux armes.

Cette vision des choses fit bondir Eugene Forsey, ancien sénateur et éminent constitutionnaliste. Il fit parvenir au journal une puissante diatribe à l’effet que l’exposition, qu’il n’avait pas vue, faussait l’histoire du pays et révélait une tendance marquée vers l’américanisation en véhiculant la notion que le Canada, comme les États-Unis, avait dû se battre pour accéder à l’indépendance (doc. 1). Je lui répondis que l’exposition n’avait rien à voir avec les États-Unis et reflétait avant tout notre héritage européen. Qu’elle racontait un volet de l’histoire d’un pays dans sa marche vers une plus grande maturité (doc. 2). M. Forsey me fit alors parvenir une lettre exprimant la crainte d'avoir été induit en erreur par la publicité du journal, mais il ne comprenait toujours pas comment l’exposition pouvait montrer une foule de drapeaux et de documents écrits ou figurés. « Combien de drapeaux le Canada a-t-il eu ? » demandait-il. Le titre anglais de l’exposition, The Maple Leaf Forever New, le mystifiait totalement.

En effet, la quête d’un drapeau national canadien avait débuté quelques années après la Confédération. Pendant près d’un siècle, les Canadiens avaient soumis au gouvernement des milliers de propositions pour un drapeau national. De plus, plusieurs Red Ensign canadiens avaient rivalisé avec l’Union Jack pour occuper la place d’emblème du pays (voir : http://www.encyclopediecanadienne.ca/fr/article/le-drapeau-national-du-canada/ et fig. 1). ). Les Archives nationales du Canada conservent des mètres de documentation relatifs à ces drapeaux. Quant au titre anglais, il s’inspire du chant patriotique “The Maple Leaf Forever” d’Alexander Muir auquel “new” est ajouté pour souligner que les symboles par leur nature se renouvellent constamment dans leur représentation et parfois dans leur sens. Ceci est vrai, aussi bien pour la fleur de lis (fig. 2) que pour la feuille d’érable. En 1965, la feuille stylisée au centre du drapeau canadien revêtait une forme jamais vue auparavant. Deux ans plus tard, une nouvelle feuille triangulée servait d’emblème pour le centenaire de la Confédération canadienne (fig. 3). Depuis 1968, deux types de feuilles d’érable sont apparus au centre du logo d’Air Canada et de nombreuses variantes de la feuille se retrouvent sur Internet. En ajoutant new, je voulais conférer au titre une auréole de mystère qui piquerait la curiosité du public.

On oublie facilement que le drapeau du Canada a des origines lointaines. Pour devenir la figure centrale du drapeau national, la feuille d’érable, acceptée comme emblème du Canada au début du XIXe siècle, a dû voler la vedette au castor, symbole du pays depuis le XVIIe siècle (voir : http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/les-origines-du-castor-et-de-la-feuille-drsquoeacuterable-comme-emblegravemes-canadiens.html). Elle a eu à supplanter les symboles coloniaux comme les fleurs de lis, les léopards d’Angleterre et l’Union Jack qu’on arborait en Amérique du Nord depuis des siècles.

M. Forsey s’accommoda de mes clarifications, mais il n’en demeure pas moins surprenant que ses reproches comme ceux de Duguid réagissaient à des affirmations douteuses parues dans la presse et non au contenu d’expositions que ni l’un ni l’autre n’avaient visitées.

En 1969, j’avais effectué les recherches et rédigé le catalogue d’une exposition intitulée Heraldry in Canada/L’art héraldique au Canada, réunissant 153 pièces, montée par les Archives publiques du Canada et ouverte lors de la réunion annuelle de la Société héraldique du Canada. Tous les journaux de la région avaient rapporté l’événement. L’un des comptes rendus, généralement bien fait, confondait la licorne mythique avec un cheval et contenait quelques imprécisions qui pouvaient déranger ceux qui cherchent la petite bête. Je reçus à cet effet, un appel téléphonique du colonel Archer Fortescue Duguid, un historien qui avait conçu quelques insignes et drapeaux militaires et avait contribué à donner au drapeau du Canada les émaux blanc et rouge en insistant que celles-ci étaient les couleurs nationales telles que consignées dans les armoiries du Canada.

Sans avoir vu l’exposition, Duguid me reprochait toutes les erreurs qu’il avait cru repérer dans le journal. Il me faisait sentir qu’il était l’expert incontesté en la matière et qu’un blanc-bec comme moi était mal venu d’envahir sa chasse gardée. Étant jeune et inaccoutumé à ce genre de critiques, je me défendis très mal. Mais ceci était sans doute salutaire, car il avait vidé son sac et il ne semble pas avoir poussé plus avant son opprobre.

Une deuxième volée de critiques concernait une exposition intitulée The Maple Leaf Forever New / Vive la feuille d’érable, montée en 1990 par le Musée canadiens des civilisations pour célébrer le 25e anniversaire de l’unifolié. Une annonce publicitaire parue dans The Ottawa Citizen donnait à l’exposition le thème de « lutte pour l’indépendance après la Confédération ». Ces mots pouvaient choquer, car si le Canada avait connu quelques rébellions, il avait acquis son indépendance progressivement sans recours aux armes.

Cette vision des choses fit bondir Eugene Forsey, ancien sénateur et éminent constitutionnaliste. Il fit parvenir au journal une puissante diatribe à l’effet que l’exposition, qu’il n’avait pas vue, faussait l’histoire du pays et révélait une tendance marquée vers l’américanisation en véhiculant la notion que le Canada, comme les États-Unis, avait dû se battre pour accéder à l’indépendance (doc. 1). Je lui répondis que l’exposition n’avait rien à voir avec les États-Unis et reflétait avant tout notre héritage européen. Qu’elle racontait un volet de l’histoire d’un pays dans sa marche vers une plus grande maturité (doc. 2). M. Forsey me fit alors parvenir une lettre exprimant la crainte d'avoir été induit en erreur par la publicité du journal, mais il ne comprenait toujours pas comment l’exposition pouvait montrer une foule de drapeaux et de documents écrits ou figurés. « Combien de drapeaux le Canada a-t-il eu ? » demandait-il. Le titre anglais de l’exposition, The Maple Leaf Forever New, le mystifiait totalement.

En effet, la quête d’un drapeau national canadien avait débuté quelques années après la Confédération. Pendant près d’un siècle, les Canadiens avaient soumis au gouvernement des milliers de propositions pour un drapeau national. De plus, plusieurs Red Ensign canadiens avaient rivalisé avec l’Union Jack pour occuper la place d’emblème du pays (voir : http://www.encyclopediecanadienne.ca/fr/article/le-drapeau-national-du-canada/ et fig. 1). ). Les Archives nationales du Canada conservent des mètres de documentation relatifs à ces drapeaux. Quant au titre anglais, il s’inspire du chant patriotique “The Maple Leaf Forever” d’Alexander Muir auquel “new” est ajouté pour souligner que les symboles par leur nature se renouvellent constamment dans leur représentation et parfois dans leur sens. Ceci est vrai, aussi bien pour la fleur de lis (fig. 2) que pour la feuille d’érable. En 1965, la feuille stylisée au centre du drapeau canadien revêtait une forme jamais vue auparavant. Deux ans plus tard, une nouvelle feuille triangulée servait d’emblème pour le centenaire de la Confédération canadienne (fig. 3). Depuis 1968, deux types de feuilles d’érable sont apparus au centre du logo d’Air Canada et de nombreuses variantes de la feuille se retrouvent sur Internet. En ajoutant new, je voulais conférer au titre une auréole de mystère qui piquerait la curiosité du public.

On oublie facilement que le drapeau du Canada a des origines lointaines. Pour devenir la figure centrale du drapeau national, la feuille d’érable, acceptée comme emblème du Canada au début du XIXe siècle, a dû voler la vedette au castor, symbole du pays depuis le XVIIe siècle (voir : http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/les-origines-du-castor-et-de-la-feuille-drsquoeacuterable-comme-emblegravemes-canadiens.html). Elle a eu à supplanter les symboles coloniaux comme les fleurs de lis, les léopards d’Angleterre et l’Union Jack qu’on arborait en Amérique du Nord depuis des siècles.

M. Forsey s’accommoda de mes clarifications, mais il n’en demeure pas moins surprenant que ses reproches comme ceux de Duguid réagissaient à des affirmations douteuses parues dans la presse et non au contenu d’expositions que ni l’un ni l’autre n’avaient visitées.