Globe Crests of Early Navigators

Auguste Vachon, Outaouais Herald Emeritus

A number of early European navigators were granted crests (the part above the shield and helmet) which included a terrestrial globe. Given that Juan Sebastián Elcano, Francis Drake, and Olivier Van Noort all circumnavigated the earth, it seems natural that they should have chosen a globe to include in their achievement of arms. But the entitlement to a terrestrial sphere may also have been viewed as a sort of badge specific to the early circumnavigators. As for Christopher Columbus, he probably had nothing to do with the introduction of a globe in his crest. For both Columbus and Drake, the exact coat of arms they were entitled to is not clear because several versions were created.

Christopher Columbus (1451-1506): reached the New World in 1492

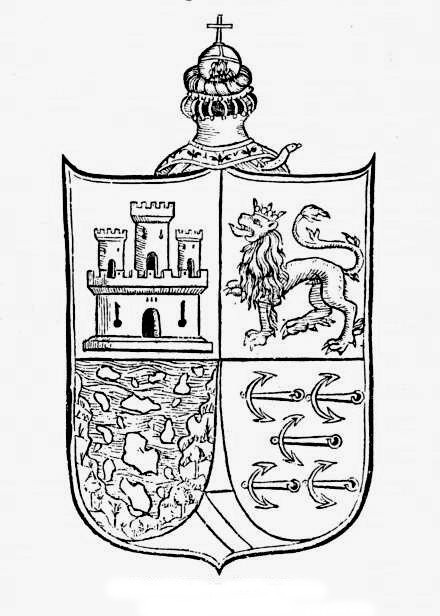

Many works describe a terrestrial globe topped by a cross as the crest of Christopher Columbus’ achievement of arms (fig. 1-2). There was no such crest in the arms granted him on 20 May 1493 by the Catholic Monarchs, Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon. In 1502 Columbus modified his arms for his two sons Diego and Fernando, but there was still no mention of a crest. The 1502 arms are featured with Columbus’ 1502 Book of Privileges which records the privileges he received from the Spanish crown, with a view to ensuring his welfare and succession. The text of the original grant of arms is reproduced with subsequent modifications to the arms on the site: http://www.cristobal-colon.com/sobre-armas-ineditas-del-escudo-de-cristobal-colon/. The arms of 1493 and 1502 are also illustrated in Wikipedia: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crist%C3%B3bal_Col%C3%B3n or https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cristoforo_Colombo. It is likely that the Admiral of the Ocean Sea, as Columbus was titled, never added a helmet and crest to his arms and never saw such appendages. It seems that someone, somewhere along the line, could not resist giving him a globe with a cross to convey the idea that he had Christianized the New World.

Many works describe a terrestrial globe topped by a cross as the crest of Christopher Columbus’ achievement of arms (fig. 1-2). There was no such crest in the arms granted him on 20 May 1493 by the Catholic Monarchs, Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon. In 1502 Columbus modified his arms for his two sons Diego and Fernando, but there was still no mention of a crest. The 1502 arms are featured with Columbus’ 1502 Book of Privileges which records the privileges he received from the Spanish crown, with a view to ensuring his welfare and succession. The text of the original grant of arms is reproduced with subsequent modifications to the arms on the site: http://www.cristobal-colon.com/sobre-armas-ineditas-del-escudo-de-cristobal-colon/. The arms of 1493 and 1502 are also illustrated in Wikipedia: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crist%C3%B3bal_Col%C3%B3n or https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cristoforo_Colombo. It is likely that the Admiral of the Ocean Sea, as Columbus was titled, never added a helmet and crest to his arms and never saw such appendages. It seems that someone, somewhere along the line, could not resist giving him a globe with a cross to convey the idea that he had Christianized the New World.

Fig. 1. The arms of Christopher Columbus having a terrestrial globe with a cross as crest, first represented by Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés in La historia general y natural de las Indias, 1535. The motto on the bordure is Por Castilla y por León nuevo mundo halló Colón (For Castile and León, Columbus discovered a new world). From José Amador de los Ríos, Historia general y natural de las Indias, islas y tierra firme del mar Océano de Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo (Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia, 1851), p. 633.

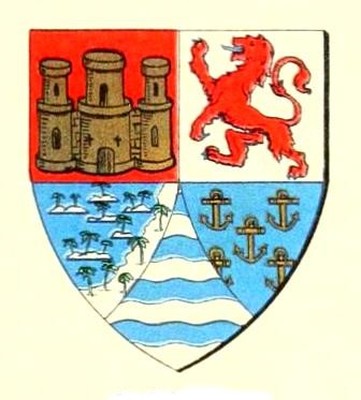

Fig. 2. Here, as in figure 1, the arms of Columbus are basically the same as reproduced in his 1502 Book of Privileges with a helmet and crest added. The triangle division in the point of the shield is called enty in point from the French (enté en pointe). Its top part is red and its lower part gold with a blue bend (see a colour illustration from the Book of Privileges: https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/1492/columbus.html). Reproduced from Oviedo’s Cronica of 1547 in Justin Winsor, Christopher Columbus and How He Received and Imparted the Spirit of Discovery (Boston, New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1892), p. 250. An illustrated edition of the Book of Privileges, translated and edited by Helen Nader, was published by University of California Press, c. 1996.

There are a number of arms attributed to Columbus such as a little-known rendering reproduced at the end of the article “Sobre armas inéditas del escudo de Cristobal Colón” which can be viewed on this site: http://www.cristobal-colon.com/sobre-armas-ineditas-del-escudo-de-cristobal-colon/. The drawing is from a manuscript entitled Colección de armas y blasones de Indias compiled from various authors by Fernando Martínez de Huete (1767) and kept in the National Library of Spain in Madrid. The bordure of the arms is inscribed with a variation on the rhyme associated with Columbus “A Castilla, y a León nuebo [sic] mundo dió Colón” (Columbus gave the New World to Castile and León). The third quarter features three bars (horizontal bands) as do the arms of the Sotomayors. This gives some vague credence to a theory advanced by Alfonso Philippot Abeledo in his work La identidad de Cristobal Colón (5th ed., 1994) wherein he claims that Pedro Álvarez de Sotomayor [Soutomaior] Count of Caminha, also called Pedro Madruga, is the true identity of Christopher Columbus, see: http://newworlddiscovery.blogspot.ca/2007/07/identity-of-columbus-part-i_26.html.

Claude-François Ménestrier gives Columbus a shield with Castile impaling León and a blue and white sea with five gold islands on a triangle in base (enty in point). He further adds a helmet with mantling and an orb with a cross as a crest. With the crest are the verses “A Castilla y a León / Mundo Nuevo dió Colón.” Ménestrier further informs us that these arms were borne this way by the descendant of Columbus, the Duke of Veragua, Admiral of the Indies and Marquis of Xamayca (Xaymaca or Jamaica). An illustration of the Columbus arms can be seen in his work: Claude-François Ménestrier, Le véritable art du blason, et l’origine des armoiries, Lyon, Thomas Amaulry, 1675, pp. 242-243: https://books.google.ca/books?id=DBw2syJJuzIC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

The arms attributed to Columbus in many works today are as in figure 3. This version may have been a misinterpretation, a modification by descendants, or simply an effort to embellish the arms of 1502. As we have seen, the arms of 1493 and 1502 (four years before Columbus died) are well documented and, unless some compelling discovery should come to light to supersede this information, we should leave it at that.

Claude-François Ménestrier gives Columbus a shield with Castile impaling León and a blue and white sea with five gold islands on a triangle in base (enty in point). He further adds a helmet with mantling and an orb with a cross as a crest. With the crest are the verses “A Castilla y a León / Mundo Nuevo dió Colón.” Ménestrier further informs us that these arms were borne this way by the descendant of Columbus, the Duke of Veragua, Admiral of the Indies and Marquis of Xamayca (Xaymaca or Jamaica). An illustration of the Columbus arms can be seen in his work: Claude-François Ménestrier, Le véritable art du blason, et l’origine des armoiries, Lyon, Thomas Amaulry, 1675, pp. 242-243: https://books.google.ca/books?id=DBw2syJJuzIC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

The arms attributed to Columbus in many works today are as in figure 3. This version may have been a misinterpretation, a modification by descendants, or simply an effort to embellish the arms of 1502. As we have seen, the arms of 1493 and 1502 (four years before Columbus died) are well documented and, unless some compelling discovery should come to light to supersede this information, we should leave it at that.

Fig. 3. Arms attributed to Christopher Columbus. From John Woodward, A Treatise on Heraldry British and Foreign (1896), vol. 2, plate VI, after p. 84.

Juan Sebastián Elcano (1476–1526): circumnavigation 1519–1522

Since the inclusion of Columbus’ globe was likely posthumous, Juan Sebastián Elcano was probably the first explorer to receive a terrestrial globe crest after he completed the first voyage around the world, an expedition begun by Ferdinand Magellan who was killed in 1521. In the arms granted Elcano in 1523 by Charles V (Charles I of Spain), the motto on a globe reads Primus Circumdedisti Me (You were the first to circumnavigate me). Although this is technically correct, the assertion seems a little pretentious given the major role that Magellan also played in the circumnavigation. His achievement of arms is well documented on these sites: https://heraldicaargentina.blogspot.ca/2012/10/escudo-de-juan-sebastian-elcano.html and https://www.reddit.com/r/heraldry/comments/3coz7a/coat_of_arms_of_juan_sebasti%C3%A1n_elcano/.

L.G. Pine’s A Dictionary of Mottoes (1983) informs us that Manuel I the Fortunate (Manuel O Afortunado), King of Portugal and the Algarves, used the same motto as Elcano. The entry reads:

“PRIMUS CIRCUMDEDISTI ME—You are the first to encompass me. Manuel I the Fortunate (also called the Great) 1495-1521; King of Portugal, under whom Portuguese discoverers made great voyages round Africa and in the Indian Ocean; the king’s badge was a globe, to which of course the words applied.”

We know that King Manuel’s badge was an armillary globe, but did he ever use the motto attributed to him by Pine? According to the work Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration edited by Jay A. Levenson (Yale University Press, 1991, p. 146), Manuel the Fortunate’s motto was Spera in Deo et Fac Bonitatem (Hope in God and Do Good) from Psalm 136. In Portuguese, the word spera can be taken to mean hope or, homophonically, a sphere (esfera) which was the badge of Manuel I. The king also displayed this symbol on his royal banner which is divided per saltire red and white with a gold armillary sphere over all. The same type of sphere is today seen on Portugal’s flag behind the shield of arms.

Since the inclusion of Columbus’ globe was likely posthumous, Juan Sebastián Elcano was probably the first explorer to receive a terrestrial globe crest after he completed the first voyage around the world, an expedition begun by Ferdinand Magellan who was killed in 1521. In the arms granted Elcano in 1523 by Charles V (Charles I of Spain), the motto on a globe reads Primus Circumdedisti Me (You were the first to circumnavigate me). Although this is technically correct, the assertion seems a little pretentious given the major role that Magellan also played in the circumnavigation. His achievement of arms is well documented on these sites: https://heraldicaargentina.blogspot.ca/2012/10/escudo-de-juan-sebastian-elcano.html and https://www.reddit.com/r/heraldry/comments/3coz7a/coat_of_arms_of_juan_sebasti%C3%A1n_elcano/.

L.G. Pine’s A Dictionary of Mottoes (1983) informs us that Manuel I the Fortunate (Manuel O Afortunado), King of Portugal and the Algarves, used the same motto as Elcano. The entry reads:

“PRIMUS CIRCUMDEDISTI ME—You are the first to encompass me. Manuel I the Fortunate (also called the Great) 1495-1521; King of Portugal, under whom Portuguese discoverers made great voyages round Africa and in the Indian Ocean; the king’s badge was a globe, to which of course the words applied.”

We know that King Manuel’s badge was an armillary globe, but did he ever use the motto attributed to him by Pine? According to the work Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration edited by Jay A. Levenson (Yale University Press, 1991, p. 146), Manuel the Fortunate’s motto was Spera in Deo et Fac Bonitatem (Hope in God and Do Good) from Psalm 136. In Portuguese, the word spera can be taken to mean hope or, homophonically, a sphere (esfera) which was the badge of Manuel I. The king also displayed this symbol on his royal banner which is divided per saltire red and white with a gold armillary sphere over all. The same type of sphere is today seen on Portugal’s flag behind the shield of arms.

Sir Francis Drake (c. 1540-1596): circumnavigation 1577-1580

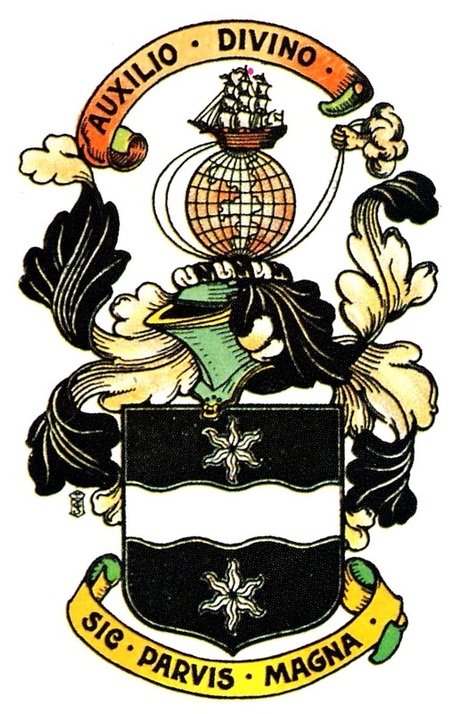

Perhaps the best known crest to feature a globe is that of Sir Francis Drake which was granted him on 20 June 1581 by Robert Cooke, Clarenceux King of Arms. The full achievement of arms is described in Sir Bernard Burke’s General Armory (1884) as: Arms―''Sable a fess wavy between two pole stars argent; Crest—A ship under reef [sails reefed] drawn round a terrestrial globe with a cable by a hand out of the clouds all proper; Mottoes―Over the crest: Auxilio divino [With divine aid]; under the arms: Sic parvis magna [Thus great things arise from small].'' This description corresponds closely with figure 4. The motto at the top thoroughly reflects the imagery of the crest which illustrates that Drake was guided and protected by the hand of God during his circumnavigation of the globe. The motto below is open to several interpretations; possibly that he accomplished great things in spite of his humble origins or that the consequences of his circumnavigation would prove much greater than the exploit itself.

In figure 4, the divine hand holding the cable is on the right and pulls the ship to the left which means that Drake’s ship began its journey by heading west as was the case in reality. In many depictions (fig. 5), the cable is pulling the ship to the right of the onlooker which means an easterly direction on a globe. Thus the image is in contradiction with the direction of the journey, namely from the western hemisphere to the eastern hemisphere and back, always heading westward. Drake’s crest with a ship pulled around the earth by a cable is a sort of bulky combination with a conspicuous mechanical component. The armorial portrait (fig. 5) is inscribed at the bottom with a Latin epigram in which the earth, the pole stars and the sun take an interest in the explorer’s peregrinations: “Drake whom the encompassed earth so fully knew, / And whom at once both poles of heaven did view: / Should men forget thee, the sun could not forbear / To chronicle his fellow traveller.” Like Drake, the sun’s journey is around the world.

Perhaps the best known crest to feature a globe is that of Sir Francis Drake which was granted him on 20 June 1581 by Robert Cooke, Clarenceux King of Arms. The full achievement of arms is described in Sir Bernard Burke’s General Armory (1884) as: Arms―''Sable a fess wavy between two pole stars argent; Crest—A ship under reef [sails reefed] drawn round a terrestrial globe with a cable by a hand out of the clouds all proper; Mottoes―Over the crest: Auxilio divino [With divine aid]; under the arms: Sic parvis magna [Thus great things arise from small].'' This description corresponds closely with figure 4. The motto at the top thoroughly reflects the imagery of the crest which illustrates that Drake was guided and protected by the hand of God during his circumnavigation of the globe. The motto below is open to several interpretations; possibly that he accomplished great things in spite of his humble origins or that the consequences of his circumnavigation would prove much greater than the exploit itself.

In figure 4, the divine hand holding the cable is on the right and pulls the ship to the left which means that Drake’s ship began its journey by heading west as was the case in reality. In many depictions (fig. 5), the cable is pulling the ship to the right of the onlooker which means an easterly direction on a globe. Thus the image is in contradiction with the direction of the journey, namely from the western hemisphere to the eastern hemisphere and back, always heading westward. Drake’s crest with a ship pulled around the earth by a cable is a sort of bulky combination with a conspicuous mechanical component. The armorial portrait (fig. 5) is inscribed at the bottom with a Latin epigram in which the earth, the pole stars and the sun take an interest in the explorer’s peregrinations: “Drake whom the encompassed earth so fully knew, / And whom at once both poles of heaven did view: / Should men forget thee, the sun could not forbear / To chronicle his fellow traveller.” Like Drake, the sun’s journey is around the world.

Fig. 4. Achievement of arms of Sir Francis Drake from Arthur Charles Fox-Davies, A Complete Guide to Heraldry (1909), plate VI.

Fig. 5. Armorial portrait of Francis Drake from Francis Fletcher, The World Encompassed by Sir Francis Drake (London: Nicolas Bourne 1628), frontispiece. Found in the Hans and Hanni Kraus Sir Francis Drake Collection, Library of Congress. See original: https://www.wdl.org/en/item/624/view/1/6/

In some descriptions and depictions, a red dragon or wyvern with elevated wings is included on the ship (C. W. Scott-Giles, Some Historic Coats of Arms, part 2, p. 17 and idem, The Romance of Heraldry (1965), pp. 166-69). The wyvern harps back to a quarrel, which apparently included some physical encounter, between Sir Francis and Sir Bernard Drake. When Sir Francis was knighted, he assumed the arms of the Devon Drakes, a wyvern on a white shield (fig. 6), an appropriation which Sir Bernard claimed to be a usurpation of his armorial property. The addition of a wyvern on the ship seems to have been aimed at establishing a link between Sir Francis and the more pedigreed Drakes of Devon, the county where, in fact, the navigator was born. The actual granting patent reads: “a field of sable, a fess wavy between two stars Argent. The helm adorned with a globe terrestrial, upon the height whereof is a ship under sail trained [pulled] about the same [the earth] with golden hawsers [thick ropes or cables] by the direction of a hand appearing out of the clouds, all in proper colour, with these words Auxilio divino [spelling modernized].” A red wyvern on a ship would be an important feature in a crest; something that must be included in the heraldic description. Since the grant of 1581 does not mention such a creature, it seems apparent that Sir Francis Drake was never granted the red monster even if one appears in an early draft and some subsequent depictions of his arms. Therefore, figure 4, with no dragon on the ship, seems the correct depiction of his armorial achievement which corresponds to the description in Burke’s General Armory. A fascinating analysis of the subject by Arthur J. Jewers, F.S.A., “The Arms of Sir Francis Drake” is found here: http://ukga.org/WesternAntiquary/Drakearms.html.

Fig. 6. The traditional red wyvern of the Drakes of Devon. From John Woodward, A Treatise on Heraldry British and Foreign (1896), vol. 1, plate XXX, after p. 304.

Olivier Van Noort (1558-1627): circumnavigation 1598–1601

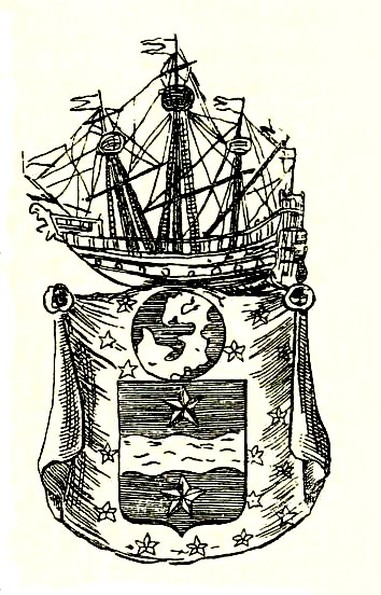

Another interesting addendum to the Drake arms is that the explorer Olivier Van Noort adopted a very similar device, namely: Azure a fess wavy rippled proper between two stars Or, as a crest a sailing ship on a terrestrial globe, behind the globe and shield a blue mantle strewn with gold stars (fig. 7). The Jesuit heraldist Ménestrier gives the description and depiction of Van Noort’s armorial design as he saw it on his tomb in the choir of St. Bartholomew’s Church at Schoonhoven in the Netherlands (Claude-François Ménestrier, Le véritable art du blason, et l’origine des armoiries, Lyon, Thomas Amaulry, 1675, pp. 242-243 : https://books.google.ca/books?id=DBw2syJJuzIC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false).

Noort is often accused of plagiarism for adopting arms so closely resembling Drake’s. This is technically true, but since Drake was the first English seaman to sail around the world (1577–80) and Van Noort the first Dutchman to accomplish the same exploit (1598-1601), it is possible that Van Noort opted for similar arms out of admiration for Drake or out of a sense of fraternity with him.

Another interesting addendum to the Drake arms is that the explorer Olivier Van Noort adopted a very similar device, namely: Azure a fess wavy rippled proper between two stars Or, as a crest a sailing ship on a terrestrial globe, behind the globe and shield a blue mantle strewn with gold stars (fig. 7). The Jesuit heraldist Ménestrier gives the description and depiction of Van Noort’s armorial design as he saw it on his tomb in the choir of St. Bartholomew’s Church at Schoonhoven in the Netherlands (Claude-François Ménestrier, Le véritable art du blason, et l’origine des armoiries, Lyon, Thomas Amaulry, 1675, pp. 242-243 : https://books.google.ca/books?id=DBw2syJJuzIC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false).

Noort is often accused of plagiarism for adopting arms so closely resembling Drake’s. This is technically true, but since Drake was the first English seaman to sail around the world (1577–80) and Van Noort the first Dutchman to accomplish the same exploit (1598-1601), it is possible that Van Noort opted for similar arms out of admiration for Drake or out of a sense of fraternity with him.

Fig. 7. Arms of Olivier Van Noort from John Woodward, A Treatise on Heraldry British and Foreign (1896), vol. 2, p. 251. Compare with figure 4

Terrestrial Globes on the Shield

Several other navigators were granted a terrestrial globe placed directly on their shield, namely Captain James Cook and Sir John Ross. Hyacinthe-Yves-Philippe-Potentien de Bougainville added a globe to the family shield to highlight his explorations and those of his father Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, a famous navigator who was aide-de-camp to General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm during the Seven Year’s War and distinguished himself during the American Revolutionary War against Britain. Illustrations of their coats of arms are easily found on the web.

The blazon (heraldic description) of the chief (upper portion) of Sir John Ross’ shield is ridiculously convoluted. Arms--''gules, three estoiles in chevron between as many lions rampant argent; Chief--and for an honourable augmentation a chief or, thereon a portion of the terrestrial globe proper, the true meridian described thereon by a line passing from north to south sable, with the Arctic Circle azure within the place of the Magnetic Pole in latitude 70o 5’ 17” and longitude 96o 46’ 45” west designated by an inescutcheon gules charged with a lion passant guardant of the first [or]; the magnetic meridian shown by a line of the fourth [azure] passing through the inescutcheon with a corresponding circle also gules to denote more particularly the said place of the magnetic pole; the words following inscribed on the chief viz. Arctæos numine fines'' (By the will of God, the North Pole).

It is impossible from normally sized imagery of Sir John’s chief (fig. 8) to distinguish what is on the small shield within the circle marking the North Pole. Needless to say that this is very poor heraldic design. I had doubts about the spelling of the word arctæos found in the inscription on the globe. A check in several works such as Burke’s General Armory revealed the same spelling in all cases, but I was unable to find a Latin declension corresponding to arctæos. Arctos is a feminine noun which can mean the North Pole, and Artictus and arctous are adjectives that refer to the north or the arctic, but none of these words have the declension arctæos. Is it a mistake? Perhaps a Latin expert reading this would have the answer.

Several other navigators were granted a terrestrial globe placed directly on their shield, namely Captain James Cook and Sir John Ross. Hyacinthe-Yves-Philippe-Potentien de Bougainville added a globe to the family shield to highlight his explorations and those of his father Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, a famous navigator who was aide-de-camp to General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm during the Seven Year’s War and distinguished himself during the American Revolutionary War against Britain. Illustrations of their coats of arms are easily found on the web.

The blazon (heraldic description) of the chief (upper portion) of Sir John Ross’ shield is ridiculously convoluted. Arms--''gules, three estoiles in chevron between as many lions rampant argent; Chief--and for an honourable augmentation a chief or, thereon a portion of the terrestrial globe proper, the true meridian described thereon by a line passing from north to south sable, with the Arctic Circle azure within the place of the Magnetic Pole in latitude 70o 5’ 17” and longitude 96o 46’ 45” west designated by an inescutcheon gules charged with a lion passant guardant of the first [or]; the magnetic meridian shown by a line of the fourth [azure] passing through the inescutcheon with a corresponding circle also gules to denote more particularly the said place of the magnetic pole; the words following inscribed on the chief viz. Arctæos numine fines'' (By the will of God, the North Pole).

It is impossible from normally sized imagery of Sir John’s chief (fig. 8) to distinguish what is on the small shield within the circle marking the North Pole. Needless to say that this is very poor heraldic design. I had doubts about the spelling of the word arctæos found in the inscription on the globe. A check in several works such as Burke’s General Armory revealed the same spelling in all cases, but I was unable to find a Latin declension corresponding to arctæos. Arctos is a feminine noun which can mean the North Pole, and Artictus and arctous are adjectives that refer to the north or the arctic, but none of these words have the declension arctæos. Is it a mistake? Perhaps a Latin expert reading this would have the answer.

Fig. 8. The arms of Sir John Ross. From Arthur Charles Fox-Davies, The Art of Heraldry (1904), p. 394. Fox-Davies blazons the full achievement of arms as does Sir Bernard Burke`s General Armory. Both works are available on the internet.

***

The fact that several early navigators adopted similar globe crests points to a certain degree of emulation as if they viewed their exploits as being on a similar footing and worthy of a like symbol. Another point demonstrated here is that people with similar achievements or organizations with similar goals tend to adopt similar symbols. This is apparent today by the individuals and corporate bodies with world activities that have included a globe in the emblems they were granted by the Canadian Heraldic Authority. At this point of writing (4/12/2016), I have found 19 such globes in the emblems of the Public Register of Arms, Flags and Badges of Canada. Another aspect brought to light in this article is that people, collectively or individually, are inclined to change their armorial bearings even after they are granted and without necessarily recording these changes with the granting authority. This practice tends, as we have seen, to create a great deal of confusion as to the exact composition of the emblems by which some armigers are identified.

N.B. All the web sites in this article were accessed on 9 December 2016.

N.B. All the web sites in this article were accessed on 9 December 2016.