Chapter 3

The Dominion Shield

From Confederation to the time it was granted arms in 1921, Canada used a quartered shield which included emblems representing Canada’s provinces and territories. A shield with the arms of the first four provinces to join Confederation was granted to be used as a Great Seal for Canada in 1868. As new provinces joined Confederation, their devices, taken from provincial seals or designed by heraldic amateurs, were placed on the shield. The whole was made even busier by the addition of a crown above the shield, branches of maple or oak around it, and a beaver below, frequently on a log. It was widely believed by Canadian and British authorities that the 1868 shield constituted the official emblem of Canada, but that it should include only the four original arms. They thought that if the additional quarters and other elements external to the shield were removed, Canada’s heraldic house would be in order. When the government realized that the quartered shield with the arms of four provinces had been granted for use as a Great Seal, and not as arms for the country, Canadian officials saw a golden opportunity to get rid of the much-criticized multi-province shield and to give the country an entirely new emblem.

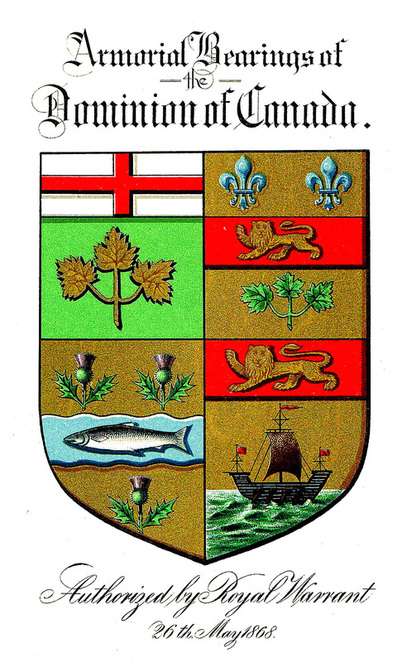

The royal warrant of Her Majesty Queen Victoria granting individual arms to each of the four original provinces forming Confederation was dated 26 May 1868. The content of these new arms seems to have been proposed by the Canadian delegates who had gone to England in November 1866 and had stayed there until the spring of 1867 to negotiate the final terms of union between the Canada East, Canada West, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. An undated memorandum contains the original proposals. It suggested for Ontario the Union Jack with its three crosses to emphasize the almost equal blend of English, Scots and Irish colonists within the province, and a sprig of three maple leaves, which was the “distinctive provincial badge in both Upper and Lower Canada.” For the arms of New Brunswick, the proposal was a ship as found in the arms today with the curious addition of a horse to designate “the House of Brunswick (although properly representative of the House of Hanover only).” “The ship refers to the shipping which is the principal employment and occupation of the Province.’ The components proposed for the other provinces would eventually be retained in the actual grant. The memorandum also proposed a nationals emblem: “The Arms of the Dominion to be quarterly, comprising the Coats of Arms of the four provinces in their order of Precedence” [1]

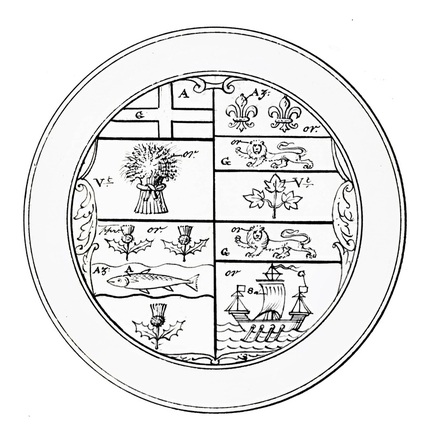

On 8 April 1868, Sir Charles George Young, Garter King of Arms, sent drawings of the proposed arms to the Colonial Office for the approval of the Duke of Buckingham and Chandos, secretary of state for the colonies. The drawings had departed from the original proposal by giving Ontario a cross of St. George instead of a Union Jack and a gold wheat sheaf instead of a sprig of maple. In the New Brunswick arms, the horse which, as we have seen, was the emblem of Hanover was replaced by a gold lion on red derived from the arms of the House of Brunswick. The Duke informed Garter through Sir Frederick Rogers, under secretary for the colonies, that in “communications.... with the Delegates from the North American Provinces, a desire was expressed for the adoption of the Maple Leaf in the Arms of Ontario”. He was therefore proposing, “if it could properly be retained,” that the original sprig of maple leaves be substituted to the wheat sheaf proposed by Garter (fig. 1). [2]

The royal warrant of Her Majesty Queen Victoria granting individual arms to each of the four original provinces forming Confederation was dated 26 May 1868. The content of these new arms seems to have been proposed by the Canadian delegates who had gone to England in November 1866 and had stayed there until the spring of 1867 to negotiate the final terms of union between the Canada East, Canada West, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. An undated memorandum contains the original proposals. It suggested for Ontario the Union Jack with its three crosses to emphasize the almost equal blend of English, Scots and Irish colonists within the province, and a sprig of three maple leaves, which was the “distinctive provincial badge in both Upper and Lower Canada.” For the arms of New Brunswick, the proposal was a ship as found in the arms today with the curious addition of a horse to designate “the House of Brunswick (although properly representative of the House of Hanover only).” “The ship refers to the shipping which is the principal employment and occupation of the Province.’ The components proposed for the other provinces would eventually be retained in the actual grant. The memorandum also proposed a nationals emblem: “The Arms of the Dominion to be quarterly, comprising the Coats of Arms of the four provinces in their order of Precedence” [1]

On 8 April 1868, Sir Charles George Young, Garter King of Arms, sent drawings of the proposed arms to the Colonial Office for the approval of the Duke of Buckingham and Chandos, secretary of state for the colonies. The drawings had departed from the original proposal by giving Ontario a cross of St. George instead of a Union Jack and a gold wheat sheaf instead of a sprig of maple. In the New Brunswick arms, the horse which, as we have seen, was the emblem of Hanover was replaced by a gold lion on red derived from the arms of the House of Brunswick. The Duke informed Garter through Sir Frederick Rogers, under secretary for the colonies, that in “communications.... with the Delegates from the North American Provinces, a desire was expressed for the adoption of the Maple Leaf in the Arms of Ontario”. He was therefore proposing, “if it could properly be retained,” that the original sprig of maple leaves be substituted to the wheat sheaf proposed by Garter (fig. 1). [2]

Fig. 1 Drawing inscribed “Great Seal for Canada,” 1868. Ontario still has a wheat sheaf, but the horse in the arms of New Brunswick has been exchanged for a lion as in the granted arms. Library and Archives Canada, photo C-33849.

In the case of the province of Quebec, fleurs-de-lis were introduced into the upper portion (the chief) to acknowledge the French origins of the inhabitants of the province. The three fleurs-de-lis of Royal France had been reduced to two and the colours reversed to blue on gold rather than gold on blue. This modification of the original royal arms was no doubt deemed necessary to avoid suggesting the revival of the old English claim to the throne of France which had been expressed by the presence of fleurs-de-lis in the arms of the United Kingdom up to 1801. The changes thus became a courteous gesture meant to recognize French heritage without the offending connotation that three gold fleurs-de-lis on blue could have had. The original memorandum had stated that for the Province of Quebec, besides the sprig of maple leaf, “...two Fleurs de Lys are adopted to indicate the French origin of the greater portion of the population of this Province; and a Lion of England to indicate its connection with this Country”. [3] Since the delegates were consulted, it is probable that the Canada East (Quebec) delegates, George-Étienne Cartier and Hector-Louis Langevin had requested the fleurs-de-lis and, given the situation, had accepted only two fleurs-de-lis and the reversal of colours. With the 1868 grant, it was the first time since 1763, that the fleurs-de-lis representing royalist French heritage had received official status within the province.

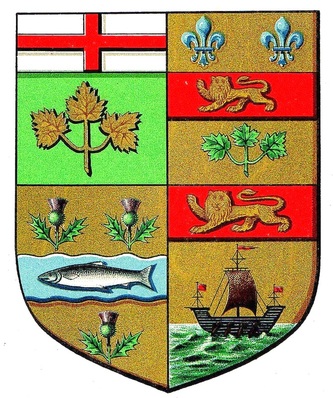

Besides granting arms to the four provinces, Queen Victoria's warrant specified:

“And We are further pleased to declare that the said United Provinces of Canada being one Dominion under the name of Canada shall upon all occasions that may be required use as a Common Seal to be called the Great Seal of Canada which said Seal shall be composed of the Arms of the said Four Provinces Quarterly All which Armorial Bearings are set forth in this Our Royal Warrant.” [4] (fig. 2)

Besides granting arms to the four provinces, Queen Victoria's warrant specified:

“And We are further pleased to declare that the said United Provinces of Canada being one Dominion under the name of Canada shall upon all occasions that may be required use as a Common Seal to be called the Great Seal of Canada which said Seal shall be composed of the Arms of the said Four Provinces Quarterly All which Armorial Bearings are set forth in this Our Royal Warrant.” [4] (fig. 2)

Fig. 2 Arms of four provinces on one shield granted to Canada for a Great Seal in 1868.

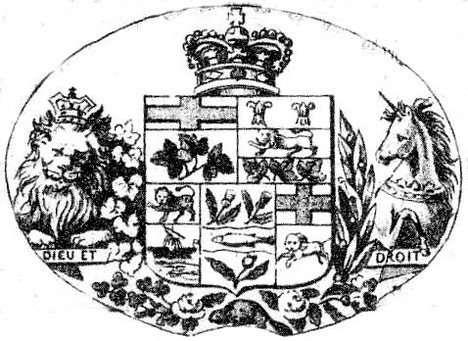

The warrant was illustrated with the arms of the four provinces and with the quartered arms. However, when the actual Great Seal of Canada, engraved by the J. S. and A. B. Wyon, arrived in Canada in early 1870, it was found to contain Queen Victoria seated on the throne as the central figure, holding sceptre and orb, with the royal arms displayed below the throne and above it the motto Dieu et mon droit. The shields of the provinces were there, but instead of being presented quarterly, were attached individually to oak trees, two on either side of the throne (fig.3). The Wyon Brothers, Alfred Benjamin and Joseph Shepherd, had designed and executed the seal “by Her Majesty's command” and had consulted an architect:

“In working out the architectural details, Messrs. Wyon have availed themselves of the able assistance of Mr. T. H. Watson, of Nottingham place, an architect who, a few years since, carried off all the honours open to students in the Royal Academy, and in the Royal Institute of British Architects.” [5]

“In working out the architectural details, Messrs. Wyon have availed themselves of the able assistance of Mr. T. H. Watson, of Nottingham place, an architect who, a few years since, carried off all the honours open to students in the Royal Academy, and in the Royal Institute of British Architects.” [5]

Fig. 3 The first Great Seal of Canada designed by the Wyon Brothers. Library and Archives Canada, photo C-6792.

How the design of the new Great Seal came about remains a mystery, but a Great Seal of this type would normally have the effigy of the sovereign, something of which the Wyon Brothers would have been well aware, Alfred Benjamin being Chief Engraver to Her Majesty’s Seals. In any case, it was widely believed that, the royal warrant of 1868 had granted arms to Canada and, indeed, it could be argued that a form of grant was implied. The warrant stated that the quartered arms were for use as a Great Seal and, if a coat of arms appears on a country's Great Seal, such arms are normally the arms of the country. A national emblem consisting of the quartered arms had been specified in the original memorandum, and high ranking British officials believed that arms had been granted.

In transferring the 1868 warrant to the governor general, the secretary of state for the colonies referred to “Her Majesty's Warrant of Assignment of Armorial Bearings for the Dominion and Provinces of Canada”. The flag authorized for the governor general in 1870 displayed the quartered arms in centre of the Union flag and that same year Canadian government vessels were authorized to fly the Blue Ensign with the same arms in the fly giving them further credence as the emblem of the nation. The same shield was later authorized to be added in the fly of the Red Ensign and flown from merchant vessels registered in Canada by Admiralty warrant of 1892, creating what would be called the Canadian Red Ensign. The exact wording of the 1892 warrant was “with the Canadian Coat of Arms in the fly”. [6] The governor general used the same expression in his official correspondence with the Colonial Office. [7] Even the College of Arms seemed to endorse the idea. A copy of the quartered arms received from that venerable institution bore the inscription: “I hereby certify that the above are the arms of the Dominion of Canada as recorded in the College of Arms London. - College of Arms - 5 February 1903 - A. S. Scott-Gatty - York Herald - Acting Registrar”. [8] But neither the efforts of Joseph Pope, under-secretary of state for Canada, nor the Admiralty warrant could completely prevent other devices to be added to the shield as new provinces joined Confederation. These multiple arms shields were placed on the Red Ensign, on some prominent government and civic buildings, on the seals and letterheads of some government departments, on many types of souvenirs such as postcards, and on ceramic souvenirs and tableware, even complete table services. [9]

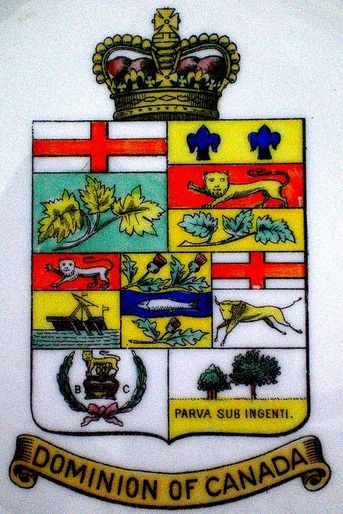

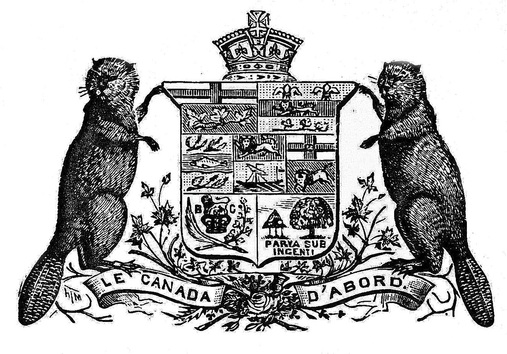

The 1868 quartered arms were almost immediately viewed by the general public as being the proper arms of the country and, by May 1871 and possibly earlier, were placed in the fly of the Red Ensign to spontaneously create a new flag for the country (fig. 4). [10] As new provinces joined Confederation, they were represented on the shield by both granted arms and other devices. Usually, the royal crown was placed on top of the shield and a beaver on a log underneath. The shield was often surrounded by maple leaves or branches of maple, or a combination of branches such as maple and oak (figs 4-5).

In transferring the 1868 warrant to the governor general, the secretary of state for the colonies referred to “Her Majesty's Warrant of Assignment of Armorial Bearings for the Dominion and Provinces of Canada”. The flag authorized for the governor general in 1870 displayed the quartered arms in centre of the Union flag and that same year Canadian government vessels were authorized to fly the Blue Ensign with the same arms in the fly giving them further credence as the emblem of the nation. The same shield was later authorized to be added in the fly of the Red Ensign and flown from merchant vessels registered in Canada by Admiralty warrant of 1892, creating what would be called the Canadian Red Ensign. The exact wording of the 1892 warrant was “with the Canadian Coat of Arms in the fly”. [6] The governor general used the same expression in his official correspondence with the Colonial Office. [7] Even the College of Arms seemed to endorse the idea. A copy of the quartered arms received from that venerable institution bore the inscription: “I hereby certify that the above are the arms of the Dominion of Canada as recorded in the College of Arms London. - College of Arms - 5 February 1903 - A. S. Scott-Gatty - York Herald - Acting Registrar”. [8] But neither the efforts of Joseph Pope, under-secretary of state for Canada, nor the Admiralty warrant could completely prevent other devices to be added to the shield as new provinces joined Confederation. These multiple arms shields were placed on the Red Ensign, on some prominent government and civic buildings, on the seals and letterheads of some government departments, on many types of souvenirs such as postcards, and on ceramic souvenirs and tableware, even complete table services. [9]

The 1868 quartered arms were almost immediately viewed by the general public as being the proper arms of the country and, by May 1871 and possibly earlier, were placed in the fly of the Red Ensign to spontaneously create a new flag for the country (fig. 4). [10] As new provinces joined Confederation, they were represented on the shield by both granted arms and other devices. Usually, the royal crown was placed on top of the shield and a beaver on a log underneath. The shield was often surrounded by maple leaves or branches of maple, or a combination of branches such as maple and oak (figs 4-5).

Fig. 4 Early “Canadianized” Red Ensign with the four-province shield in the fly and the addition of a crown, a beaver and maple leaves, c. 1868-73. The shield and ornaments became faded with use and difficult to recognize at a distance such as on the sea.

Fig. 5 The type of shield, with additions, that appeared in the fly of the first “Canadianized” Red Ensigns.

All the provinces used seals before being granted arms and whatever was depicted on these seals came to be viewed as arms after Confederation. This misconception between arms and seals has often been attributed to the ignorance of Canadians in matters of heraldry, but mistaking the imagery on seals for coats of arms seems almost natural, since granted arms are frequently used on seals. In fact, another powerful influence was at play. On 16 December 1865, the secretary of state for the colonies advised the governor general that pursuant section 3 of the Colonial Naval Defence Act, Act. 28, Vict., Cap. XIV, vessels owned or in the service of the colony were to fly the Blue Ensign with the badge or seal of the colony in the fly. He further asked to be supplied, for the Lords of the Admiralty, with “a correct drawing of the Seal or Badge which is to form the distinguishing mark of Canadian Vessels.” [11] The next year, the secretary of state for the colonies specifically asked to be supplied with a complete drawing of the ensigns flown by Canadian government vessels. [12] These requests were taking place prior to Confederation when only Nova Scotia and Newfoundland had properly granted arms.

Three years later, an order in council dated 7 August 1869, authorized the governors or administrators of British colonies to use the Union Jack with the badge of the colony in the centre. This brought about still another circular despatch, dated September 14, asking the Colonies to supply a depiction of the badges they used: “Under any circumstances, it will be desirable that I should be furnished with a Drawing of the Badge with which it is proposed to distinguish the Flag of the colony under your Government.” [13] From 1870, the governor general of Canada was authorized to fly from boats and other vessels on which he was embarked, the Union Flag with the four-province shield in centre on a white roundel and within a wreath of maple leaves topped by the royal crown. The same year, the lieutenant governors were authorized to fly from boats and other vessels on which they were embarked the Union Flag bearing in centre the provincial arms or badge on a white roundel within a wreath of maple leaves. [14]

A further circular despatch issued on August 23, 1875, clearly placed the imagery of seals and arms on the same footing:

“In those colonies in which no device has been fixed upon, coloured drawings of the distinctive device on the Seal of the Colony, exclusive of the Royal Arms, as that will be the Badge which will hereafter be adopted in all cases, and the publication in the Admiralty Flag Book of these devices will cause the Flags of the different colonies to be more widely known.” [15]

Another letter from the Colonial Office in 1878 perpetuates the same confusion. Although it does point out that only a four-province shield is granted to Canada, and advocates that steps might be taken to have the “entire Arms of the Dominion” made regular, it goes on to convey the view of the Lords of the Admiralty that the arms of the Dominion might be amended “...so as to include the badges (or a portion of them) of the additional provinces now included in the Dominion”. [16]

With these recurrent despatches from officials in high places, it is little wonder that the provinces began to view their seals as legitimate heraldic devices and, having invented colours for them to comply with the wishes of the secretary of state for the colonies, the coloured imagery of seals came to be included in the Dominion shield. The earliest known example of a five-province shield, the four original provinces and Manitoba (fig. 6), is found on the front page of L'Opinion publique of 2 January 1873. The Order in Council of 2 August 1870, authorizing the seal of Manitoba, had contained a rather awkward heraldic description of the seal which seemed to be confused with arms. [17]

The colony of British Columbia decided to adopt its own device inspired by the crest of the Royal Arms of England, namely a lion standing on the royal crown and similarly crowned. As seen on figures 7 and 8, the crown itself is flanked with the letters B.C., and the whole is placed between branches of laurel (sometimes oak and laurel). The Dictionary of Canadian Biography attributes this design, which was approved by Admiralty on 9 July 1870, to Richard Clement Moody, a former lieutenant governor of the colony: http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/moody_richard_clement_11E.html.

Fig. 6 Five-province shield with the addition of the supporters and motto of the United Kingdom. From “Bird's eye view of the City of Ottawa… 1876” drawn by Herm. Brosius. Library and Archives Canada.

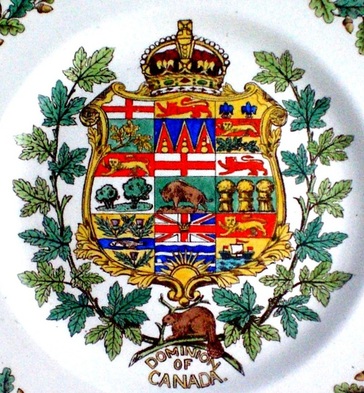

The first known seven-province Dominion shield is seen on the front page of the Canadian Illustrated News of 5 December 1874. It includes the depictions of the seals of Manitoba and Prince Edward Island, the device adopted by the colony of British Columbia in 1870 as well as the four arms granted to Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in 1868. The same shield, within a wreath of maple branches, with the royal crown on top and a beaver below adorns the medal of the Dominion of Canada at the Philadelphia exhibition of 1876. [18] While the Canadian Illustrated News of 9 June 1877 still displays the five-province shield on its front page, the issue June 30 of that year, which is dedicated to the tenth anniversary of Confederation, displays the seven-province one. This version remained in use until the early twentieth century (fig. 7-8). By 1914, the secretary of state for the colonies had himself become confused and was prompted to ask, after seeing both a seven and a nine-quarter shield in the Admiralty Flag Book: “I shall be glad to learn whether it is in contemplation to make any change in design of the flags for the Dominion which were approved in His Majesty's Privy Council for Canada on 28th February 1870.” [19] Joseph Pope, under-secretary of state for External Affairs from 1909, replied that no changes were contemplated, and that any shield with more than the original four provinces, as granted in 1868, was unauthorized. [20]

Fig. 7 The shield of the Dominion from 1874 to c. 1905. Added to the original four provinces is the imagery of the seals of Manitoba and Prince Edward Island, and the device adopted by British Columbia in 1870. Porcelain plate by Schmidt & Co., Altrohlau (Bohemia), Austria, Gemma mark, c. 1905. A. & P. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

Fig. 8 The arms of the Dominion, in use from 1874 to c. 1905, augmented with the usual crown, beavers as supporter and a motto. The floral badges of England, Scotland and Ireland, mixed with maple leaves, appear around the motto scroll, an idea which will be retained for the arms granted to Canada in 1921. Illustration from T. Martin Castorologia (Montreal: Wm. Drysdale & Co., 1892), p. 204.

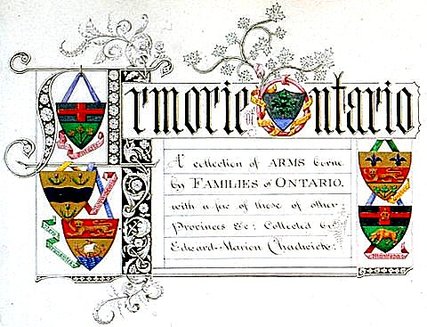

In 1903, the imagery of a new seal for British Columbia, designed in 1895 by Reverend Arthur John Beanlands, began to replace the former seal on the Dominion shield. [21] Other arms designed by Edward Marion Chadwick, a Toronto barrister, for Prince Edward Island, the Northwest Territories and the Yukon also arrived on the scene (fig. 9). [22] From 1905 to 1907, Manitoba, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Prince Edward Island, and Alberta were granted proper arms and, as a result, the unofficial creations of Beanlands and Chadwick gradually disappeared from the shield, including those of the Yukon and Northwest Territories. [23]

Fig. 9 The arrangement of the arms is as follows: 1st row from left to right, Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia; 2nd row New Brunswick (all four official), British Columbia (unofficial designed by Beanlands), Prince Edward Island; 3rd row Northwest Territories, Yukon (all three unofficial Chadwick creations) and Manitoba (unofficial from its seal). Unmarked plate made in Austria or Germany, c. 1903-05. A. & P. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

Though the seven-province shield was in wide use from 1876 to 1905, when dating artefacts displaying this combination, the collector should keep in mind that there is no cut-off date in such matters. In other words, one can find a particular shield some ten years after it should have gone out of use. The printing date of postcards is rarely indicated, and a postcard with the Dominion arms could still be on sale several years after the original printing. Likewise, a medal could be struck sometime before the actual presentation or be presented over many years.

Joseph Pope believed that the four-province shield, although granted for a seal, was the true arms of Canada to which no other devices should be added. [24] Wanting to put an end to the chaos of the multi-arms composition, he had an image of the four provinces only printed in 1904 by Mortimer and Co. with the inscription “Armorial Bearings of the Dominion of Canada. Authorized by Royal Warrant 26th May 1868.” (fig. 10) [25] Consequently a four-province shield does not necessarily date from after Confederation. It could date from around 1905, but is even more likely to date from after the First World War when the use of the four-province shield became more widespread especially in connection with more official items such as medals. [26] Somewhere between 1934 and 1950, Grimwades of England produced a large series of souvenirs and small table pieces under the name Royal Winton. Many of these were illustrated with the four-province shield, although it was more than a decade after Canada had been granted the present arms (fig. 11). Occasionally, merchants unwittingly offer such four-province souvenirs as being just after Confederation, although they date from much later: caveat emptor.

Joseph Pope believed that the four-province shield, although granted for a seal, was the true arms of Canada to which no other devices should be added. [24] Wanting to put an end to the chaos of the multi-arms composition, he had an image of the four provinces only printed in 1904 by Mortimer and Co. with the inscription “Armorial Bearings of the Dominion of Canada. Authorized by Royal Warrant 26th May 1868.” (fig. 10) [25] Consequently a four-province shield does not necessarily date from after Confederation. It could date from around 1905, but is even more likely to date from after the First World War when the use of the four-province shield became more widespread especially in connection with more official items such as medals. [26] Somewhere between 1934 and 1950, Grimwades of England produced a large series of souvenirs and small table pieces under the name Royal Winton. Many of these were illustrated with the four-province shield, although it was more than a decade after Canada had been granted the present arms (fig. 11). Occasionally, merchants unwittingly offer such four-province souvenirs as being just after Confederation, although they date from much later: caveat emptor.

Fig. 10 Four-province shield printed in 1904 by Mortimer and Co. at the request of Joseph Pope. Property of A. & P. Vachon.

Fig. 11 The 1868 shield appeared on souvenirs after Canada had been granted a proper coat of arms in 1921. On a plate by Grimwades (Royal Winton), England, dated 1934-50. A. & P. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

Pope would have gladly included the other provinces in the Dominion shield if their arms had been official. When asked by Major Frederick S. Maude, secretary to the governor general, why there were only four provinces on his print, he replied that he fully agreed that all the provinces should be represented, a goal he had been trying to achieve for seven years. [27] When he had finally obtained granted arms for all the provinces, Alberta being the last one to comply in May 1907, he wrote Ambrose Lee, York Herald at the College of Arms in England, asking for a drawing which would include all the provinces on one shield. [28] Lee sent him a drawing, but with the advice: “It seems to me that it might be well to have a Royal Warrant authoritatively settling the order in which the arms recently granted should be quartered with the four coats which were originally granted.” [29]

Unless the warrant had spelt out that such a shield was the official emblem of Canada, the absence of granted arms for the country would have been perpetuated. The idea that the four-province arms of Canada were not official came from Edward Marion Chadwick. [30] Early in 1907, he told Pope: “I am rather under the impression that the arms of Canada as recognized by Authority are actually founded on no authority at all, excepting the Great Seal.” [31] A bit later, Pope was able to tell Chadwick: “I think we are both agreed that it would be better to have a distinct emblem for Canada, rather than a combination of all the provincial arms. It is useless to try to get the ear of the Government for anything of the kind just now, but directly the session is over, I will see if anything can be done. I have it always in my mind.” [32]

Pope’s correspondence with Lee in September of that year clearly showed that he recognized the unsuitability of the quartered arms. [33] In 1909, he wrote:

“It is commonly supposed that the Arms of Canada must necessarily be an aggregation of the Arms of all the Provinces, but this is a mistake. However proper the idea might have seemed forty years ago, I think it would scarcely do to amend the Arms of the Dominion every time a Province took it into its head to amend its own. My idea is that the next change in the Arms of the Dominion should be to discard the original Arms altogether, and to adopt some emblem distinct from the Arms of any of the Provinces, something that would speak of our double ANCESTRY, by which I mean something distinctively British and monarchical, together with the Bourbon lilies, and possibly an Indian or two with a few maple leaves thrown in.” [34]

Except for the Amerindians which he would later reject, Pope was even then spelling out many of the elements which would eventually be included in Canada's coat of arms. In 1904, Pope had convinced the minister of Public Works that the proper flag to fly from the Parliament Tower was the Union Flag, or Union Jack, which was the only authorized flag to represent Canada on land, and that the Red Ensign with the multi-province shield in the fly should be removed. [35] He was very proud of this achievement: “In my private opinion there is not such thing as a distinctively Canadian flag on land, and I venture to hope there may never be one, for personally, the ‘Union Jack’, pure and simple is good enough for me.” [36]

Unless the warrant had spelt out that such a shield was the official emblem of Canada, the absence of granted arms for the country would have been perpetuated. The idea that the four-province arms of Canada were not official came from Edward Marion Chadwick. [30] Early in 1907, he told Pope: “I am rather under the impression that the arms of Canada as recognized by Authority are actually founded on no authority at all, excepting the Great Seal.” [31] A bit later, Pope was able to tell Chadwick: “I think we are both agreed that it would be better to have a distinct emblem for Canada, rather than a combination of all the provincial arms. It is useless to try to get the ear of the Government for anything of the kind just now, but directly the session is over, I will see if anything can be done. I have it always in my mind.” [32]

Pope’s correspondence with Lee in September of that year clearly showed that he recognized the unsuitability of the quartered arms. [33] In 1909, he wrote:

“It is commonly supposed that the Arms of Canada must necessarily be an aggregation of the Arms of all the Provinces, but this is a mistake. However proper the idea might have seemed forty years ago, I think it would scarcely do to amend the Arms of the Dominion every time a Province took it into its head to amend its own. My idea is that the next change in the Arms of the Dominion should be to discard the original Arms altogether, and to adopt some emblem distinct from the Arms of any of the Provinces, something that would speak of our double ANCESTRY, by which I mean something distinctively British and monarchical, together with the Bourbon lilies, and possibly an Indian or two with a few maple leaves thrown in.” [34]

Except for the Amerindians which he would later reject, Pope was even then spelling out many of the elements which would eventually be included in Canada's coat of arms. In 1904, Pope had convinced the minister of Public Works that the proper flag to fly from the Parliament Tower was the Union Flag, or Union Jack, which was the only authorized flag to represent Canada on land, and that the Red Ensign with the multi-province shield in the fly should be removed. [35] He was very proud of this achievement: “In my private opinion there is not such thing as a distinctively Canadian flag on land, and I venture to hope there may never be one, for personally, the ‘Union Jack’, pure and simple is good enough for me.” [36]

Union Jack flying from Bonaventure Railway Station, Montreal, c. 1908.

In other words, Pope wanted the Union Flag to be flown on land and the Red Ensign with the four-province shield in the fly to be flown by merchant ships registered in Canada. Following the same logic, one may ask why he did not impose the Royal Arms as appropriate for Canada? He had, in fact, started using the royal arms to identify the Department of the Secretary of State and had proposed that the Department of Militia and Defence follow suit. [37] But there remained his belief that Canada was granted arms in 1868.

Besides pointing out that the quartered arms probably had no official status as arms for Canada, Chadwick had been of genuine help to Pope from 1896 to 1907 as he struggled to bring Manitoba, Prince Edward Island, British Columbia, Saskatchewan and Alberta into the official heraldic fold. Chadwick's arms for Saskatchewan had been accepted by both the province and the College of Arms with minor adjustments in the colours. [38] He had also proposed arms for Alberta, but the province rather opted for a geographic or scenic depiction of its territory. [39] He designed the crest and supporters for Ontario and helped to ensure that proper procedures were followed in making them official. [40]

At one point, Pope and Chadwick almost came to words over the use of the Red Ensign, the flag of the governor general and those of the lieutenant-governors. Pope contended that these flags, having been authorized by the Admiralty, could only be used on vessels, while Chadwick maintained that their use on land was authorized and quoted examples to support his assertion. [41] When Chadwick insisted, Pope quoted from the Colonial Office list for 1904, chapter XX, p. 446:

“1) The Royal Standard shall be flown at Government House on the King's Birthday, and on the days of His Majesty's Accession and Coronation.

“2) The Union Flag, without the badge of the Colony, shall be flown at Government House from sunrise to sunset on other days.”

Pope repeated his view that the Admiralty had no jurisdiction on land, and summed up his variance of opinion with Chadwick as follows: “The whole difference between us, as I understand it, is that you seem to be under the impression that there is such a thing as a Canadian flag or a Canadian variation of the Union Jack.” [42]

No doubt sensing some irritation, Chadwick simply stated that they were both after answers and that Pope might consult some experts in Europe. [43] As it turned out, Chadwick's reasoning had merit. Some time later the Colonial Office would confirm that, although the Canadian Red Ensign had been authorized for Canadian vessels, the propriety of its use on land depended upon local law and usages. [44] Pope had been exposed to so much confusion regarding the emblems of Canada that he refused to consider anything which was not sanctioned by an official document. Chadwick, on the other hand, seemed to better realize that, beyond officialdom, emblems need to have a dynamic relationship with the group they represent, even if some usages and practices are not officially sanctioned.

For some time now, Chadwick had been up to some mischief of his own which went counter to Pope's efforts to make provincial arms official. During his studies, Chadwick had come upon a German shield, very likely that of the Kingdom of Prussia or that of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, which contained, on one shield, all the arms of the territories forming one union. This spread of colour which he called an écu complet had so caught his fancy that he decided to create such a shield for the British Empire. He designed a first shield which he sent to The Genealogical Magazine, a London publication in 1900, with the encouragement of the editor, Elliot Stock.

The strange feature of this écu complet was that it included, along with the original four official grants, the unofficial arms of Manitoba and Chadwick’s own fanciful creations for Bermuda, Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island, the Northwest Territories and British Columbia. [45] Later he prepared an “improved” version for Queen Victoria, which she accepted. In this new version, the unofficial arms of British Columbia, designed by the Reverend Arthur John Beanlands, were substituted to Chadwick’s earlier creation (fig. 9). The device had been adopted by a provincial Order-in-Council on 19 July 1895 to be displayed on the provincial Great Seal from 1896. Finally Chadwick sent a version of an écu complet for Canada to the Governor General. In this new creation, he stressed that symmetry was essential and to avoid seven quarters or even eight which was difficult to arrange, he had introduced one of his most recent creations for the Yukon. The expression écu complet is not current heraldic terminology. Chadwick had his own definition: “The term ‘Ecu complet’ signifies the quartering in one shield of the armorials of, or representing the countries, states, or territories under one Sovereign.”

In complete contradiction with Pope, Chadwick, at least at one time, believed that a province had the right to assume its own coat of arms since lieutenant-governors in council were empowered to alter the seals of the provinces:

“Every government, paramount or subordinate, must have a great seal, and therefore has an inherent right to compose, as it may please, the devices to be displayed on such seal. Such devices are heraldic, that is, pictorially symbolic. … whether skilfully and tastefully composed or otherwise, are generally, at least, if not quite always, in armorial form. Therefore every government has a generally recognized inherent right to devise arms for its own use. In the case of subordinate governments, such rights may be limited by the superior government, but by some express act and not merely by implication. In the absence of any such express act, the inherent right stands good.

“Colonial arms so assumed and borne are expressly recognized by the Admiralty, apart from the seal on which they are borne; bearing the arms, is, of course, recognized by all authorities.” [46]

By Chadwick’s own admission, his “écus complets” were spreading like wildfire simply from the fact that there was a thirst for a Canadian shield which included all the provinces. [47] This thirst was expressed by an increasingly more cluttered design to give all parts of Canada their place on the Dominion shield. Chadwick's écu complet appeared on a large number of postcards, on certificates, on medals, on hundreds of Red Ensigns and on hundreds of porcelain wares. [48]

As soon as Manitoba, Prince Edward Island, British Columbia and Saskatchewan were granted arms between May 10, 1905 and August 25, 1906 and prior to Alberta receiving its grant on May 30, 1907, a new écu complet appeared incorporating these new arms. In order to respect the écu complet's spirit which was symmetry, the old arms of the Northwest Territories were dropped from the shield to create a symmetrical design of three rows with three shields each (fig. 12). As soon as Alberta received a grant on May 30, 1907, the arms of the Yukon were removed from the Dominion shield in favour of the same principle (fig. 13). The present arms of the Yukon, granted in 1956, are partly based on Chadwick's creation. Alan Beddoe, their designer, once told me that Chadwick's bezants on piles (triangles) expressed very well the popular expression: “Thar's gold in them thar hills.”

Besides pointing out that the quartered arms probably had no official status as arms for Canada, Chadwick had been of genuine help to Pope from 1896 to 1907 as he struggled to bring Manitoba, Prince Edward Island, British Columbia, Saskatchewan and Alberta into the official heraldic fold. Chadwick's arms for Saskatchewan had been accepted by both the province and the College of Arms with minor adjustments in the colours. [38] He had also proposed arms for Alberta, but the province rather opted for a geographic or scenic depiction of its territory. [39] He designed the crest and supporters for Ontario and helped to ensure that proper procedures were followed in making them official. [40]

At one point, Pope and Chadwick almost came to words over the use of the Red Ensign, the flag of the governor general and those of the lieutenant-governors. Pope contended that these flags, having been authorized by the Admiralty, could only be used on vessels, while Chadwick maintained that their use on land was authorized and quoted examples to support his assertion. [41] When Chadwick insisted, Pope quoted from the Colonial Office list for 1904, chapter XX, p. 446:

“1) The Royal Standard shall be flown at Government House on the King's Birthday, and on the days of His Majesty's Accession and Coronation.

“2) The Union Flag, without the badge of the Colony, shall be flown at Government House from sunrise to sunset on other days.”

Pope repeated his view that the Admiralty had no jurisdiction on land, and summed up his variance of opinion with Chadwick as follows: “The whole difference between us, as I understand it, is that you seem to be under the impression that there is such a thing as a Canadian flag or a Canadian variation of the Union Jack.” [42]

No doubt sensing some irritation, Chadwick simply stated that they were both after answers and that Pope might consult some experts in Europe. [43] As it turned out, Chadwick's reasoning had merit. Some time later the Colonial Office would confirm that, although the Canadian Red Ensign had been authorized for Canadian vessels, the propriety of its use on land depended upon local law and usages. [44] Pope had been exposed to so much confusion regarding the emblems of Canada that he refused to consider anything which was not sanctioned by an official document. Chadwick, on the other hand, seemed to better realize that, beyond officialdom, emblems need to have a dynamic relationship with the group they represent, even if some usages and practices are not officially sanctioned.

For some time now, Chadwick had been up to some mischief of his own which went counter to Pope's efforts to make provincial arms official. During his studies, Chadwick had come upon a German shield, very likely that of the Kingdom of Prussia or that of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, which contained, on one shield, all the arms of the territories forming one union. This spread of colour which he called an écu complet had so caught his fancy that he decided to create such a shield for the British Empire. He designed a first shield which he sent to The Genealogical Magazine, a London publication in 1900, with the encouragement of the editor, Elliot Stock.

The strange feature of this écu complet was that it included, along with the original four official grants, the unofficial arms of Manitoba and Chadwick’s own fanciful creations for Bermuda, Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island, the Northwest Territories and British Columbia. [45] Later he prepared an “improved” version for Queen Victoria, which she accepted. In this new version, the unofficial arms of British Columbia, designed by the Reverend Arthur John Beanlands, were substituted to Chadwick’s earlier creation (fig. 9). The device had been adopted by a provincial Order-in-Council on 19 July 1895 to be displayed on the provincial Great Seal from 1896. Finally Chadwick sent a version of an écu complet for Canada to the Governor General. In this new creation, he stressed that symmetry was essential and to avoid seven quarters or even eight which was difficult to arrange, he had introduced one of his most recent creations for the Yukon. The expression écu complet is not current heraldic terminology. Chadwick had his own definition: “The term ‘Ecu complet’ signifies the quartering in one shield of the armorials of, or representing the countries, states, or territories under one Sovereign.”

In complete contradiction with Pope, Chadwick, at least at one time, believed that a province had the right to assume its own coat of arms since lieutenant-governors in council were empowered to alter the seals of the provinces:

“Every government, paramount or subordinate, must have a great seal, and therefore has an inherent right to compose, as it may please, the devices to be displayed on such seal. Such devices are heraldic, that is, pictorially symbolic. … whether skilfully and tastefully composed or otherwise, are generally, at least, if not quite always, in armorial form. Therefore every government has a generally recognized inherent right to devise arms for its own use. In the case of subordinate governments, such rights may be limited by the superior government, but by some express act and not merely by implication. In the absence of any such express act, the inherent right stands good.

“Colonial arms so assumed and borne are expressly recognized by the Admiralty, apart from the seal on which they are borne; bearing the arms, is, of course, recognized by all authorities.” [46]

By Chadwick’s own admission, his “écus complets” were spreading like wildfire simply from the fact that there was a thirst for a Canadian shield which included all the provinces. [47] This thirst was expressed by an increasingly more cluttered design to give all parts of Canada their place on the Dominion shield. Chadwick's écu complet appeared on a large number of postcards, on certificates, on medals, on hundreds of Red Ensigns and on hundreds of porcelain wares. [48]

As soon as Manitoba, Prince Edward Island, British Columbia and Saskatchewan were granted arms between May 10, 1905 and August 25, 1906 and prior to Alberta receiving its grant on May 30, 1907, a new écu complet appeared incorporating these new arms. In order to respect the écu complet's spirit which was symmetry, the old arms of the Northwest Territories were dropped from the shield to create a symmetrical design of three rows with three shields each (fig. 12). As soon as Alberta received a grant on May 30, 1907, the arms of the Yukon were removed from the Dominion shield in favour of the same principle (fig. 13). The present arms of the Yukon, granted in 1956, are partly based on Chadwick's creation. Alan Beddoe, their designer, once told me that Chadwick's bezants on piles (triangles) expressed very well the popular expression: “Thar's gold in them thar hills.”

Fig. 12 All the arms on this shield are granted except those of the Yukon in the middle upper row. Alberta, which was granted arms on 30 May 1907, is missing. Wedgwood plate 1908. A. & P. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

Fig. 13 Nine-province shield (all granted arms) held by the divinities Ceres and Mercury on the façade of the Dominion Express Building, built in 1912 on St-Jacques St., Montreal. Photo by Jonathan Good.

Later, Chadwick seems to have had second thoughts about his creations. At one point he told Pope: “An ‘Ecu complet’ is rather an academic production, and stands on a somewhat different basis from the authorized and recognized arms of one central government.” [49] If Chadwick helped Pope refine some of his thinking, there is clear evidence that Pope influenced Chadwick who began having his own misgivings about the composite Dominion shield. He proclaimed his opposition to the use of seals instead of heraldically constituted arms; he criticized the lack of symmetry in a number of compositions; he deplored the use of the Crown which was not authorized and also the use of the composite shield on the red ensign where only the four quartered arms should have been present. He further condemned the unauthorized additions to the shield such as the crown, beaver and wreath. While Chadwick created endless confusion with his own creations, he journeyed hand in hand with Pope towards the realization that Canada needed new arms of its own. [50]

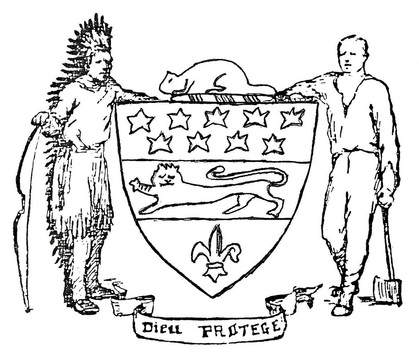

A serious public movement to have distinct arms granted to Canada began after the First World War. Canada's participation in that tragic event had produced at least one positive result: a growing sense that Canada was no longer a colony and that it was in its interest to manage its own affairs at home and abroad. A corollary of this fledging nationalism was that Canada should possess its own national emblem, and that this should happen in 1917 at the fiftieth anniversary of Confederation. In May, Victor Morin, a well known Montreal heraldist, sent a memorandum to the Royal Society of Canada outlining his proposal for distinct Canadian arms. The proposal consisted of a blue shield with a red horizontal band in the centre (a fess) displaying a gold lion walking and looking at the spectator (passant guardant) for England. In the upper shield (chief) were nine gold leaves for the provinces and in base a gold fleur-de-lis for France. The crest on top of the shield was a beaver lying down (couchant) in natural colours (proper). The motto was Dieu protège. The right supporter was a pioneer leaning on an axe and the left supporter an Amerindian leaning on a bow (fig. 14). Morin was confident that his design was highly appropriate and would readily be approved by the College of Arms. [51] However, his red band on a blue field broke one of the basic rules of heraldry which forbids the placing of a colour on a colour. Nine gold leaves in chief was less cumbersome than nine provinces, but it still made for a busy design that would become busier if new provinces were created. On the other hand, besides symbols of England and France, it was Canadian in content.

A serious public movement to have distinct arms granted to Canada began after the First World War. Canada's participation in that tragic event had produced at least one positive result: a growing sense that Canada was no longer a colony and that it was in its interest to manage its own affairs at home and abroad. A corollary of this fledging nationalism was that Canada should possess its own national emblem, and that this should happen in 1917 at the fiftieth anniversary of Confederation. In May, Victor Morin, a well known Montreal heraldist, sent a memorandum to the Royal Society of Canada outlining his proposal for distinct Canadian arms. The proposal consisted of a blue shield with a red horizontal band in the centre (a fess) displaying a gold lion walking and looking at the spectator (passant guardant) for England. In the upper shield (chief) were nine gold leaves for the provinces and in base a gold fleur-de-lis for France. The crest on top of the shield was a beaver lying down (couchant) in natural colours (proper). The motto was Dieu protège. The right supporter was a pioneer leaning on an axe and the left supporter an Amerindian leaning on a bow (fig. 14). Morin was confident that his design was highly appropriate and would readily be approved by the College of Arms. [51] However, his red band on a blue field broke one of the basic rules of heraldry which forbids the placing of a colour on a colour. Nine gold leaves in chief was less cumbersome than nine provinces, but it still made for a busy design that would become busier if new provinces were created. On the other hand, besides symbols of England and France, it was Canadian in content.

Fig. 14 Arms proposed for Canada by the heraldist Victor Morin in 1917.

After presenting his initial proposal to the Royal Society, Morin sent it to the members of the Antiquarian and Numismatic Society located in Château Ramezay in Montreal, to Édouard-Zotique Massicotte and Régis Roy and to others. [52] Morin's initiative gave rise to four alternate designs created by Chadwick, John Charles Alison Heriot, Herbert George Todd, and himself. These four new proposals in turn evolved into a compromise which consisted of a blue shield with a lion passant guardant between two maple leaves at the top and a fleur-de-lis below, all gold. The crest on top of the shield was a moose in natural colours and the supporters on both sides of the Shield two Amerindians, one eastern and one western, “habited in their national costume”. The motto proposed was Dieu protège le Roy, a French version of “God save the King” (fig. 15). [53]

Fig. 15 Arms proposed for Canada in 1919 by the Antiquarian and Numismatic Society of Montreal.

The compromise to reach a single design had been arduous. Morin had come to favour two maple leaves to represent French and English Canada rather than his original nine leaves to represent the provinces. He had also accepted to remove the red fess which he recognized as not being the best of heraldry. A moose had also replaced the beaver as a result of strong opposition from Chadwick. Morin's pioneer supporter was likewise abandoned for a second Indian because it was felt that this supporter should be reserved for the arms of Quebec. [54] Initially, Chadwick had been delighted with Morin's motto Dieu protège, but upon further reflection had concluded that it contained a disguised notion of republicanism and should rather be Dieu protège le Roy to express unequivocal loyalty to the Crown. [55]

In effect, much of what Morin had proposed initially was retained, but there seems to have been divergences of view within the Montreal group, at least according to Chadwick:

“The Scottish representative, the late Mr. Heriot of Montreal, wanted it to thoroughly preponderate as Scottish, which of course, was out of the question. Mr. Morin wanted it to be French. He is well versed in French Heraldry, but of the period preceding the French Revolution with all the imperfections of that period, which was one of debasement.” [56]

There were no doubt differences of opinion between Heriot and Morin, but there is also evidence of willingness to compromise. Naturally, Herriot wanted Scotland to be represented but not to the point of excluding others as we shall see in the next chapter. When it comes to Morin, Chadwick is completely off-base. There does not seem to be any recorded instance where a Canadian Francophone attempted to foist an emblem with a majority of French symbols upon the rest of Canada and this would hardly have been attempted by a man of the stature of Morin. [57]

To demonstrate this further, let us look at his actual proposal (fig. 14). The only French element is a modest fleur-de-lis in base of the shield. The much larger lion of England is featured above, and the rest of the composition is Canadian. The motto itself is French, but does not express an especially French idea. To what French period, debased or otherwise, does this design belong? Absolutely none!! Even the shape of the shield is that widely used by Chadwick himself (compare figs. 14 & 16). Of course, Morin’s creation would be greatly improved by a good rendering, and the inclusion of a helmet and mantling would make it much more attractive, but those are artistic considerations. Morin’s flexibility was demonstrated by the acceptance of a number of changes to his original design as we have seen.

In effect, much of what Morin had proposed initially was retained, but there seems to have been divergences of view within the Montreal group, at least according to Chadwick:

“The Scottish representative, the late Mr. Heriot of Montreal, wanted it to thoroughly preponderate as Scottish, which of course, was out of the question. Mr. Morin wanted it to be French. He is well versed in French Heraldry, but of the period preceding the French Revolution with all the imperfections of that period, which was one of debasement.” [56]

There were no doubt differences of opinion between Heriot and Morin, but there is also evidence of willingness to compromise. Naturally, Herriot wanted Scotland to be represented but not to the point of excluding others as we shall see in the next chapter. When it comes to Morin, Chadwick is completely off-base. There does not seem to be any recorded instance where a Canadian Francophone attempted to foist an emblem with a majority of French symbols upon the rest of Canada and this would hardly have been attempted by a man of the stature of Morin. [57]

To demonstrate this further, let us look at his actual proposal (fig. 14). The only French element is a modest fleur-de-lis in base of the shield. The much larger lion of England is featured above, and the rest of the composition is Canadian. The motto itself is French, but does not express an especially French idea. To what French period, debased or otherwise, does this design belong? Absolutely none!! Even the shape of the shield is that widely used by Chadwick himself (compare figs. 14 & 16). Of course, Morin’s creation would be greatly improved by a good rendering, and the inclusion of a helmet and mantling would make it much more attractive, but those are artistic considerations. Morin’s flexibility was demonstrated by the acceptance of a number of changes to his original design as we have seen.

Fig. 16 Title page of an unfinished album entitled “Armorie of Ontario” by Edward Marion Chadwick. Library and Archives Canada.

On September 28, 1917, F. Faithfull Begg, a retired stock broker living in England, wrote to Sir Robert Borden recommending that there should be “distinct recognition in the Royal Arms of overseas possessions”. He felt that the extension of the empire which had taken place in recent times should be “exemplified and emphasized” and that it was the proper moment to accomplish this with the advent of the House of Windsor. [58] Borden told Begg that it was “impossible at this time to give attention to such a matter”; [59] privately, however, both the prime minister and Joseph Pope viewed him as “a retired stock broker with plenty of leisure time on his hands”. Pope told Borden that “any such change is quite unnecessary since constitutional relations between Mother Country and Overseas Dominions and India have not changed”. [60]

On December 18, a memorandum with explanatory notes was sent to Governor General Devonshire by Chadwick and Todd and representatives of a number of patriotic societies in Toronto: such as the St. George's Society, the United Irish League, the St. Andrew's Society, the Sons of Scotland, the United Empire Loyalists and the Navy League of Canada. The memorandum, which included the compromise described above (fig. 15), stressed that the composite Dominion shield was inadequate, that full arms with crest supporters and motto were needed to express “the dignity of the Dominion” and that First Nation supporters were most suitable to represent Canada from East to West. It further emphasized that Amerindians predated discovery, had rendered important military services to the country including their contribution to the present war, and that they were the supporters of the arms of the Compagnie des Indes founded in 1664. It recommended that steps should be taken to make these arms official and mentioned that another memorandum would be coming from Montreal. [61]

The Antiquarian and Numismatic Society of Montreal wrote to the governor general on December 21sending the same proposal, which was conveyed by the Privy Council to the Prime Minister for the attention of Sir Joseph Pope. [62] A few days later, the proposal was also sent to the Secretary of State. [63] The Montreal proposal was the same as the Toronto one but presented in a more formal way, each paragraph being introduced by “Whereas”. [64]

In 1907, Pope had written several times to Ambrose Lee, York Herald of Arms, to discuss possible designs and had corresponded with him again on the same subject in 1915. [65] By that time, Pope had come to realize that Canada was not granted arms in 1868. In a long memorandum dated 8 June 1915 to Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden, he states this, but rather carefully: “No armorial bearings appear to have been formally granted by this Warrant [of 26 May 1868] to Canada, but the Dominion was authorized to use a Great Seal composed of the Arms of the above-mentioned four Provinces quarterly”. He saw this arrangement as “obviously a makeshift, intended merely to do duty until the question of armorial bearings for the Dominion was further thought out.” He goes on to describe the many problems he had in obtaining properly granted arms for all the provinces between 1897 and 1907. He could not escape the fact that the quartered arms were used on the blue and red ensigns and on the Union Jack as the flag of the governor general and by government departments, as well, sometimes with more than four arms. He describes the muddled situation as follows:

“The present position of the matter is this. Officially, though not so far as I can ascertain, by express warrant, the Arms of Canada to-day are those of the original four Provinces quarterly. Popularly, they consist of a Shield on which are crowded, in defiance of all heraldic proprieties, the Arms of as many Provinces as the Shield will hold. .... Whenever a Province joined the Dominion, its Arms always irregular, and sometimes grotesque from a heraldic point of view, were at once incorporated by the public (and I am sorry to say by some of the public departments as well) in the Dominion Shield. The consequence is that the Arms of Canada, as popularly understood, have become a veritable nightmare to those possessing any heraldic knowledge ... with the result that the Arms of the Dominion of Canada, as commonly employed, are a laughing stock to those acquainted with the rules of heraldry.

“Nor, assuming they were correctly quartered, do I consider, as a matter of principle, that the Arms of the Dominion should be a mere combination of those of the Provinces. ... I hold that people should be taught to look upon Canada as a separate entity, with an individuality of her own, distinct from the Provinces of which she is composed. ….

“I take the position that it is much more fitting, from the point of view of our national development, that Canada should have a distinctive device of its own, as Canada. What the device should be, I am not prepared to say, but once the principle I advocate is approved, there should not be much difficulty in carrying it into effect, Dr. Dawson's [Samuel Edward Dawson (1833-1916), King’s printer] [66] suggestions are on record in the Department of the Secretary of State of Canada, which is the Department to deal with the matter. There are also letters there from E. M. Chadwick of Toronto, and others with whom I corresponded on the subject. Dr. Doughty [Arthur Doughty, Dominion Archivist], I believe, possesses a fair knowledge of heraldry and a fine artistic sense. I would suggest that Mr. Mulvey (Thomas Mulvey, under-secretary of state for Canada) and he might confer in the matter, and I feel sure that if the subject were to be taken up with the Herald's College, between them they could evolve, not only appropriate Arms for Canada, but Crest Supporters and Motto as well. Any Arms which might be devised for Canada, it seems to me should bear some testimony to our British allegiance, and also some allusion to the late French regime, as well as, a recognition of the monarchical principle in the shape of a Crown or other regal emblem.

“The approaching jubilee of Confederation would be a fitting occasion to have this long delayed matter satisfactorily adjusted.” [67]

This document is important because it reveals the way of thinking of a key figure in the story of Canada's arms, at the very moment when this question was starting to be discussed. Many of these principles will eventually guide the future committee on Canada’s arms. Pope seems to want to reassure Borden that the new arms would emphasize allegiance to Britain and the monarchy along with recognition of French contribution to the country. He further wants to persuade him that the matter would be free of difficulty with the College of Arms, stemming from his experience as negotiator of five provincial arms between 1897 and 1907.

Curiously, in spite of his strong statement to that effect, Pope was not entirely sure that arms had not been granted to Canada in 1868. Two days after preparing his memorandum to Borden, he wrote Ambrose Lee to ask “if any armorial bearings have ever been assigned to the Dominion of Canada.” [68] If he received an answer to his question, it may not have been to his satisfaction since in 1917 he asked the opinion of George E. Foster, minister of trade and commerce: “I would ask you to read over the enclosed Royal Warrant which is always interpreted as assigning Arms to the Dominion of Canada as well as to the provinces. I think you will agree with me that it does nothing of the kind. It assigns Arms to the four provinces and a Great Seal to the Dominion, but a Great Seal is not Arms.”[69]

On December 31, Pope produced a second memorandum for Borden in response to Chadwick and the Toronto group. He was in general agreement with Chadwick who had abandoned his écu complet in favour of entirely new arms. Pope reminds the prime minister that he had sent him a memorandum on the matter in 1915, but could not get anyone in authority to act. Where Pope differed with Chadwick was in the degree of public involvement. He felt that this matter should not be handled by what was essentially a Toronto group with a few others from Montreal and Todd who resided in the States and in whose judgement he did “not attach much weight.” He wanted a wider consultation which would involve the historian Benjamin Sulte, Alfred Duclos DeCelles, author and librarian of the Library of Parliament, Martin Joseph Griffin, journalist and Parliamentary Librarian, and Arthur Doughty, Dominion Archivist.

Pope liked the shield proposed by both Montreal and Toronto, but refused to have it supported by Amerindians and did not see any necessity to include them anywhere. His objection to the beaver was unequivocal “the abortive looking animal proposed for the crest is out of place.” He thought the motto Dieu protège le roy was reminiscent of a “court legend of the days of the Bourbon Sovereigns.” The whole achievement of arms, in his opinion, emphasized far too much the “aboriginal and French periods.” He thought animals would be best as supporters and that the crest should emphasize monarchical rule. For motto, he favoured A mari usque ad mare, which Sir Leonard Tilley had found in the Bible. Pope also outlined the correct procedure to follow and stressed the importance of keeping the matter in government hands. He also felt that if the services of Chadwick were needed, he should be duly paid. [70]

On 4 February 1918, the deputy minister of the Department of Militia and Defence, Major-General Eugène Fiset, wrote to Thomas Mulvey, sending him his views on the question of Canadian arms. In preparing the memorandum, Fiset likely received help from a member of his staff, Major-General Sir Willoughby Garnons Gwatkin and Charles Frederick Hamilton, a journalist and author on the staff of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police who shared some of Fiset’s views. Be that as it may, the proposal was of a rare clarity. It set out three possibilities: 1) retaining the four-province arms and making them official; 2) using the Chadwick type of écu complet and making it official; 3) obtaining entirely new granted arms. Since the first solution was not representative and the second one was a patchwork in constant need of rearrangement, he favoured entirely new arms with crest, supporters and motto. The desired qualities of the new arms should be: instantly recognizable even at a distance, easily remembered, easily depicted, attractive, stressing unity rather than diversity, and reference to the mother country.

Fiset proposed: 1) a white field with a single large red maple leaf; 2) a white field with nine red maple leaves; 3) the addition to 1 or 2 of a bordure or double tressure (two parallel lines following the contour of the shield) on which to place of the badges of the founding nations, rose, thistle, shamrock, fleur-de-lis; 4) the addition to 1 or 2 of the Union device (union Jack) at the honour point (centre of upper shield). Of these he favoured the single red maple leaf “to denote men who had sacrificed their lives for the country and Empire” and white to represent snow and the phrase “our Lady of the Snows” which “has established itself in the language.” Proposals one and two would later be repeated by Hamilton, which means that he was likely involved in the original proposal. [71] For a crest, Fiset favoured a beaver because of its long association with Canada: “Despite the somewhat prosaic attributes of the animal, it has so long been identified with the country that it is regarded with a considerable measure of liking by the public and may be regarded as having historic claim.”

For supporters, he rejected beavers, moose, buffalo, and bear, which were all clumsy, and also the caribou which had been appropriated by Newfoundland and was difficult to draw. He much preferred lions for their universal appeal. He wanted a Latin motto to avert problems of bilingualism and proposed a few, such as Liber et tenax (free and tenacious) and Conjuncta in imperio (united in the empire).

Fiset's proposal of a red maple leaf on a white background was many years ahead of its time. Had it been adopted, the choice of a Canadian flag could have no doubt proved much easier. Strangely, after preaching simplicity to the extent that a school child could depict the arms on a slate and that one leaf spelt unity, he began to worry that a single leaf might be a little too simple and could be confused with a crest. [72] It seems obvious that his fears were unwarranted. The maple leaf would have been on a shield and not in the crest on top of the helmet, and having one single symbol that a majority of Canadians could agree to would have sent a message of unity, as well as being a highly desirable heraldic feature.

It is doubtful that Mulvey ever showed Fiset's proposal to Pope. There was no reason for him to do so at this early stage. Pope had always made it clear that he was not particularly open to suggestions that emphasized Canadian nationalism at the expense of strong ties with the United Kingdom. When Morin pressed Borden for an answer to the Numismatic and Antiquarian Society's proposal in the spring of 1918, Pope told Borden that the timing of the proposal was “inopportune.” [73] He added “I think the proposal to have two ragged looking Indians as supporters of the Dominion shield is highly inappropriate. The suggested crest and motto are also in my judgement unsuitable.” He further expressed his certainty that Chadwick was behind both suggestions. [74]

Pope surely recognized Chadwick's expertise in heraldic matters. In May 1918, he had written him asking what was the proper term for “those accessories to the Royal Arms which appear emanating from the helmet in the form of spreading branches” (mantling or lambrequins). He wondered if they were part of the royal arms. [75] Some differences between the views of Chadwick and Pope can be explained by their backgrounds. Pope was born at Charlottetown in 1854, the son of the honourable William Henry Pope, one of the Fathers of Confederation. Before becoming under-secretary of state for External Affairs he had been private secretary to Sir John A. Macdonald, and later under-secretary of state for Canada. While Pope considered himself first of all a Canadian, he resented anything which might suggest that Canadians were not British citizens in their own right. [76] He was ferociously opposed to any initiative which might weaken the cohesion of the empire. Pope looked to the British Empire for strength and salvation. [77] His remark concerning “ragged looking Indians” sounds highly racist, but this may have been partly a reaction to the way the Amerindians were depicted (see fig. 14). The essence of Pope’s opposition to such supporters was that they catered to growing nationalism rather than to the unity of the empire. Moreover, he felt he had tolerated enough interference with the Dominion arms, from Chadwick in particular. The nationalist bent of the suggested design seemed to have convinced Pope that sentiments, just after the war, were too intense and that any national emblem chosen at that time would emphasize nationalism rather than imperial unity.

Chadwick, a lawyer, was a great admirer of Indian culture. He had written on the subject and had been made honorary Chief of the Anowara (Turtle) clan of the Mohawk Nation and, on that occasion, had been given the name of Shagotyohgwisaks meaning “One who gathers the people into bands.” [78] He looked to the land for inspiration searching for what made it special and strong.

What forced the government to act was above all the unrelenting criticism from the public. Morin sarcastically notes that Canada's emblem is an agglomeration of provincial devices, some of them being sceneries rather than arms. He finds in the composition something to please everyone. Plenty of wild and fur-bearing animals to satisfy the hunter, an abundance of plants to please the botanist, all kinds of geographic features to delight a landscape painter: seascapes, prairies, mountains, perpetual snows and even sunsets. He sees there fish, cereal crops and ships, all arranged in an orgy of colours. His proposed blazon for this mess is “rainbow, (the field colours) a bouillabaisse of the same (colours)”. He pleads that, after 50 years of revamping this patchwork, the time has come for Canadians to seek armorial bearings worthy of the rank that their country will eventually occupy among the nations of the world. [79]

On 16 March 1918, Borden asked what course should be followed to obtain proper arms for Canada. [80] Considerable pressure also came from the Department of Militia and Defence. On February 8, 1919, the Deputy Minister, Major General Sir Eugène Fiset wrote to the undersecretary of state, Thomas Mulvey:

“I find the idea to be more prevalent than I had supposed, that a new coat of arms should be assigned to the Dominion; and that the termination of the war, in which Canada has taken so glorious a share, is a suitable time for applying for a grant. Therefore I venture to suggest that a Commission be appointed to advise, after consulting the College of Heralds, how hereafter the ‘Arms of the Dominion of Canada’ should be composed and blazoned.” [81]

Mulvey and the secretary of state, Martin Burrell, endorsed Fiset's idea and made proposals as to how the committee should be composed. [82] Support for the idea also came from Frederick Cook, assistant king's printer. He complained to Mulvey that he had been having trouble trying to prevent the Department of Militia and Defence from “inventing Royal Arms for themselves.” He also suggested his own slate of candidates for the committee. [83] In February 1919, Burrell informed the governor general that an ambiguous situation had developed following the 1868 “grant.” Although the warrant authorized only the quartered arms of the four original provinces, the arms of new provinces had been added to the shield as they joined Confederation. He proposed the creation of a committee “for the purpose of inquiring and reporting upon the advisability of requesting His Majesty the King, through the College of Heralds, for an amendment to the Armorial Bearings of Canada...” [84]

On December 18, a memorandum with explanatory notes was sent to Governor General Devonshire by Chadwick and Todd and representatives of a number of patriotic societies in Toronto: such as the St. George's Society, the United Irish League, the St. Andrew's Society, the Sons of Scotland, the United Empire Loyalists and the Navy League of Canada. The memorandum, which included the compromise described above (fig. 15), stressed that the composite Dominion shield was inadequate, that full arms with crest supporters and motto were needed to express “the dignity of the Dominion” and that First Nation supporters were most suitable to represent Canada from East to West. It further emphasized that Amerindians predated discovery, had rendered important military services to the country including their contribution to the present war, and that they were the supporters of the arms of the Compagnie des Indes founded in 1664. It recommended that steps should be taken to make these arms official and mentioned that another memorandum would be coming from Montreal. [61]

The Antiquarian and Numismatic Society of Montreal wrote to the governor general on December 21sending the same proposal, which was conveyed by the Privy Council to the Prime Minister for the attention of Sir Joseph Pope. [62] A few days later, the proposal was also sent to the Secretary of State. [63] The Montreal proposal was the same as the Toronto one but presented in a more formal way, each paragraph being introduced by “Whereas”. [64]

In 1907, Pope had written several times to Ambrose Lee, York Herald of Arms, to discuss possible designs and had corresponded with him again on the same subject in 1915. [65] By that time, Pope had come to realize that Canada was not granted arms in 1868. In a long memorandum dated 8 June 1915 to Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden, he states this, but rather carefully: “No armorial bearings appear to have been formally granted by this Warrant [of 26 May 1868] to Canada, but the Dominion was authorized to use a Great Seal composed of the Arms of the above-mentioned four Provinces quarterly”. He saw this arrangement as “obviously a makeshift, intended merely to do duty until the question of armorial bearings for the Dominion was further thought out.” He goes on to describe the many problems he had in obtaining properly granted arms for all the provinces between 1897 and 1907. He could not escape the fact that the quartered arms were used on the blue and red ensigns and on the Union Jack as the flag of the governor general and by government departments, as well, sometimes with more than four arms. He describes the muddled situation as follows: