The Mermaid in Canadian Heraldry and Lore

By Auguste Vachon, Outaouais Herald Emeritus

Originally published in Heraldry in Canada, 47, no. 3-4 (2013), p. 17-29.

Like the unicorn and dragon, the mermaid or siren is a universal symbol and is present in the folklore of all maritime countries. Canada is bordered by three oceans and the seal, which is the main animal credited for the mermaid legend, abounds on its coastlines. Although the recorded sightings of these legendary creatures in Canadian waters are not as numerous as might be expected, they nevertheless exist. Since the establishment of the Canadian Heraldic Authority in 1988, the mermaid has been given new life in the arms granted to individuals and corporate bodies.

Representations of mermaids probably came to Canada as figureheads perched on the bow of ships where they braved the raging seas. We know for instance that one of John Davis’ ships on his 1586 expedition to the Canadian Arctic was called the Mermayde. In the Thousand Islands (St. Lawrence River), Mermaid Island is named after a gunboat and not because a mermaid was seen there. Many other ships called mermaid or sirène are connected with the history of Canada, [1] but this mythical creature has been present in other spheres of life such as the series of essays on literary and other topics entitled “At the Mermaid Inn” published in the Globe (1892-93) by three Canadian poets, William Wilfred Campbell, Duncan Campbell Scott and Archibald Lapman.

The idea of combining fish and man can be traced back to antiquity. [2] Homer’s account of sirens (or mermaids) attempting to lure Odysseus (Ulysses) and his crew into the sea with their songs is well known. A Canadian painting in the early 1860s by Edward R. Jost depicts this theme, but the three sirens are normal naked women playing the harp without the traditional fishtail. [3] This cannot be viewed as an erroneous interpretation, since Homer does not describe the physical composition of his sirens.

The persistence of the mermaid legend to modern times seems explained by the resemblance of certain animals to humans when seen at a distance:

“... in the northern countries, are various seals, which formerly abounded upon the coasts of Western Europe, and still are to be seen in the less frequented spots. They have a way of lifting their round heads and shoulders from the water, with a queer human intelligent look upon their faces, and hugging their young to their bosoms with motherly affection.” [4]

The other sirenian sometimes quoted in the same way is the dugong whose habitat is the shallow coastal waters from the Red Sea and eastern Africa to the Philippines, New Guinea, and Northern Australia.

“Near at hand these uncouth monsters would never be mistaken for human beings; but seen at a distance, by fearful and wondering voyagers along the coast, such an error might easily happen, for they frequently stand upright among the weedy shallows of the coasts, perhaps draped with loosened vegetation like long hair, and holding to their breasts a young one who nurses from pectoral mammae much as a human baby would do.” [5]

Several species of the manatee, also mentioned as a source of the mermaid legend, are found on the Florida coast, on the northern and eastern coast of South America and on the western coast of Africa. Another species of sea cow (now extinct) was discovered by the German naturalist Georg Wilhelm Steller (Stöhler) in the coastal waters of the Komandorski Islands in the Bering Ocean off the Siberian peninsula of Kamchatka, when shipwrecked on Bering Island in 1741. Observing that the animals had an affectionate disposition and mated like humans, Steller remarked that it was these creatures that had long been taken for mermaids. [6] The fact that mermaids are viewed by sailors far away from home for long periods of time might explain their popularity in comparison with mermen.

The first sighting of mermaids in connection with the New World was reported in the Caribbean by Christopher Columbus on his first voyage:

“Yesterday [8 January 1493], when the Admiral [Columbus] went to the Rio del Oro [river of gold], he said that he saw three mermaids rising well above the sea, but were not so beautiful as they are portrayed, for their faces, in a way, resembled those of men. He said that he had seen others previously in Guinea on the Manegueta Coast [Pepper Coast].” [7]

Henry Hudson is well known in Canadian history for his quest for the Northwest Passage and he did record a mermaid sighting, but nowhere near Canada. In 1608, he set out from England in search of a Northeast Passage, a voyage that brought him to the Novaya Zemlya archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. On June 15, at North Cape on the northern tip of Norway, he reported that two of his sailors had seen a mermaid.” [8]

It seems that the first recorded Canadian sighting made by Captain Richard Whitbourne, the explorer William Hawkeridge and other crew members took place in 1610 in Saint John’s Harbour, Newfoundland, and was reported by Whitbourne:

“Now also I will not omit to relate something of a strange creature that I first saw there in the year 1610, in a morning early as I was standing by the water side, in the Harbour of Saint Johns, which I espied very swiftly to come swimming towards me, looking cheerfully, as it had been a woman, by the face, eyes, nose, mouth, chin, ears, neck and forehead. It seemed to be so beautiful, and in those parts so well proportioned, having round about upon the head, all blew streaks resembling hair, down to the neck (but certainly it was no hair) for I beheld it long, and another of my company also, yet living, that was not then far from me; and seeing the same coming so swiftly towards me, I stepped back, for it was come within the length of a long pike. Which when this strange creature saw that I went from it, it presently thereupon dived a little under water, and did swim towards the place where before I landed; whereby I beheld the shoulders and back down to the middle, to be as square, white and smooth as the back of a man, and from the middle to the hinder part, pointing in proportion like a broad hooked arrow; how it was proportioned in the forepart from the neck and shoulders, I know not; but the same came shortly after unto a boat, wherein one William Hawkeridge, then my servant, was … and the same creature did put both his hands upon the side of the boat, and did strive to come in to him and others then in the said boat: whereat they were afraid; and one of them struck it a full blow on the head; whereby it fell off from them; and afterwards it came to two other boats in the said harbour; the men in them, for fear, fled to land. This (I suppose) was a mermaid. Now because divers have written much of mermaids, I have presumed to relate what is most certain of such a strange creature … whether it were a mermaid or no, I know not; I leave it for others to judge…”[9]

This case is interesting because close proximity excludes optical illusion, but the loneliness may have played a role since the observer finds the creature well-proportioned, even beautiful. What these mariners, accustomed to sea life, really saw is cause for wonder.

Whitbourne’s account is repeated in a 1628 German edition of Theodore de Bry’s America, revamped by several other authors. In this connection, an illustration on page 5 shows three mermaids, one apparently conversing with European men on shore, another approaching the shore where people gesture at her to keep away, and another near a ship on which someone threatens her with a club. A related theme is found on a vignette of the title page where a mermaid is seen between two ships her arms stretched forward as if begging to come aboard. [10] De Bry depicted mermaids and many fabulous creatures in connection with the explorations of Christopher Columbus, Amerigo Vespucci and Ferdinand Magellan. [11]

Another creature combining a human torso with a fish tail on Canadian territory is found in an album of drawings, which was given the name of Codex Canadensis. The author, Louis Nicolas, was a Jesuit missionary who journeyed in Canada from 1664 to 1674. The drawings were meant to illustrate a manuscript by Nicolas entitled Histoire naturelle des Indes occidentales, which was never published as the missionary had hoped. Page 59 of the Codex shows a strange creature combining a fish tale with a human torso. The face appears rather feminine with long hair, but under the chin are appendages which are perhaps meant to be fins or possibly a beard. The torso and arms are scaly, the “hands” appear as smaller fishtails. The torso is separated from the large fishtail by a broad band or ridge. The French inscription translates:

“Marine monster killed by the French on the Richelieu River in New France.” The Histoire naturelle does not provide further information on this creature, but the illustration can be found on the the website of Library and Archives Canada: http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/026014/f1/4726.7.055-v5.jpg (consulted 13 Nov. 2013). [12] When exactly the monster was killed is not known, and what it was remains a mystery. It could well be that Nicolas worked from an oral description, since there is no indication that he was present at the event.

Another interesting sighting was made in 1886 by the fishermen of Gabarus, a community on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia:

“The fishermen of Gabarus, Cape Breton, have been excited over the appearances of a mermaid, seen in the waters by some fishermen a few days ago. While Mr. Bagnall, accompanied by several fishermen, was out in a boat, they observed floating on the surface of the water a few yards from the boat what they supposed to be a corpse. Approaching it for the purpose of taking it ashore, they observed it to move, when to their great surprise, it turned around in a sitting position and looked at them and disappeared. A few moments after [,] it appeared on the surface and again looked toward them, after which it disappeared altogether. The face, head, shoulders and arms resembled those of a human being, but the lower extremities had the appearance of a fish. The back of its head was covered with long, dark hair resembling a horse's mane. The arms were shaped like a human being's, except that the fingers of one hand were very long. The color of the skin was not unlike that of a human being. There is no doubt, that the mysterious stranger is what is known as a mermaid, and the first one ever seen in Cape Breton waters.” [12a]

Other Canadian sightings were reported, one near Victoria on Vancouver Island between 1870 and 1890 and another observed by ferry passengers in 1967 on a rock in Active Pass near Victoria. Accounts of the latter sighting in the Times Colonist reported that the mermaid had long blonde hair, the tail of a porpoise, and was eating a salmon at the time of the sighting. [13]

The mermaid is also connected with Canada in the myths and legends of the North American First Nations. This constitutes a fascinating area of investigation and is another witness to the universality of the mermaid phenomenon, a universality that is also reflected in the similarity of descriptions by Amerindians and Europeans, namely: a female upper body and some form of fishtail. [14] In Inuit art, which is flourishing today, the sea goddess Sedna frequently takes the shape of the traditional mermaid.

In the arms of the former Governor General Michaëlle Jean, the water spirits or Simbis supporters (Fig. 1) are very close in their outward appearance to mermaids, but have their own spiritual attributes, which are described as follows:

“Beside the shield are two Simbis, water spirits from Haitian culture who comfort souls, purify troubled waters and intervene with wisdom and foresight. Moreover, the Simbis' words are enlightening and soothing. These two feminine figures symbolize the vital role played by women in advancing social justice.” [15]

Fig. 1 Two Simbis supporting the arms of Michaëlle Jean, Governor General of Canada (2005-2010). Granted by the Chief Herald of Canada, September 20, 2005 (Vol. IV, p. 1). Reproduced by permission of the Canadian Heraldic Authority of Canada © Her Majesty in Right of Canada.

In heraldry, the human portion of the mermaid is depicted nude with well defined breasts and is usually shown combing her long hair while admiring herself in a mirror. The privy seal of Sir William O’Grady Haly, K.C.B., administrator of Canada (1874-75 and 1878), shows the mermaid in her traditional representation (Fig. 2). A map by Pierre Devaux (1613) shows two mermaids facing one another in the Atlantic Ocean below the Tropic of Cancer. The interest of these two creatures is that they are both looking in a mirror and combing their hair in the manner of the heraldic mermaid. [16] In Haitian voodoo the mermaid (Lasirèn) is a spirit (lwa) that takes possession of young women that are overly concerned with their looks and elegance. [17] This is surprisingly close to the self-admiration of the traditional heraldic mermaid with her comb and mirror. Again we are confronted with the universality of themes found in mythology.

Fig. 2 Matrix of the privy seal of Sir William O’Grady Haly, administrator of Canada. The motto Sapiens dominatur astris means “The wise man rules the stars.” Library and Archives Canada, photo C 33799.

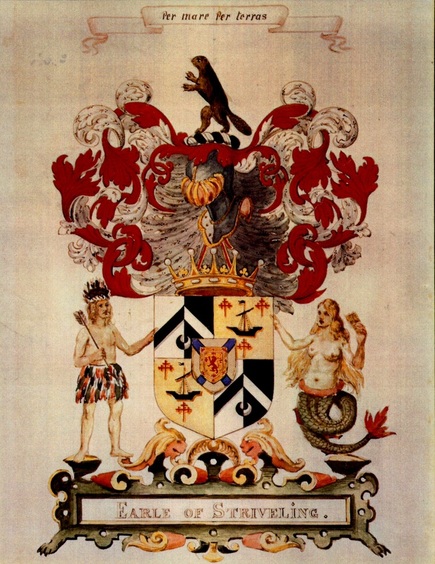

Fig. 3 The mermaid with a long convoluted tail and holding a comb is the right supporter of the arms of Sir William Alexander, Viscount of Stirling in 1630, Viscount of Canada and Earl of Stirling in 1633. Library and Archives Canada.

A number of other mermaids were granted by the Chief Herald of Canada and can be viewed with their blazons and symbolism in the Canadian Heraldic Authority’s Public Register of Arms, Flags and Badges of Canada online, by doing a search under Advanced Research; Index Armorum; Main charge: mermaid. [18]

***

Creatures combining human features and wings are frequent, because of man’s desire to fly. In the same way, ability to swim like a fish represents the conquest of the seas. It is interesting that these wishes have all been surpassed by modern technology. Surely the flame of ancient dragons is no match for the fire power of modern war machines.

Granting mermaids can give rise to situations of political correctness because of the exposed breasts. Such questions arise occasionally when arms are granted in Canada and no doubt elsewhere. Animals look too fierce and unfriendly, stick out their tongues impolitely or display their masculinity too prominently. It seems that heraldry is broadly viewed as formal and therefore prim and proper. One can argue that putting a damper on such features diminishes an art that strives to stylise by emphasizing salient physical features and to depict such traits of character as strength, courage, and the will to defend and protect. On the other hand, we live in a democratic society that should respect the wishes of the person or corporate body that will display the arms. Fortunately heraldry can usually accommodate such personal preferences. These choices rarely affect the blazon (heraldic description) so that arms can be stylized differently at a future date without contravening the original grant. What has ensured the survival of heraldry has been its flexibility. If it had not evolved rather quickly out of the framework of feudalism to embrace all types of institutions and all levels of society, chances are that it would no longer exist today.

***

Creatures combining human features and wings are frequent, because of man’s desire to fly. In the same way, ability to swim like a fish represents the conquest of the seas. It is interesting that these wishes have all been surpassed by modern technology. Surely the flame of ancient dragons is no match for the fire power of modern war machines.

Granting mermaids can give rise to situations of political correctness because of the exposed breasts. Such questions arise occasionally when arms are granted in Canada and no doubt elsewhere. Animals look too fierce and unfriendly, stick out their tongues impolitely or display their masculinity too prominently. It seems that heraldry is broadly viewed as formal and therefore prim and proper. One can argue that putting a damper on such features diminishes an art that strives to stylise by emphasizing salient physical features and to depict such traits of character as strength, courage, and the will to defend and protect. On the other hand, we live in a democratic society that should respect the wishes of the person or corporate body that will display the arms. Fortunately heraldry can usually accommodate such personal preferences. These choices rarely affect the blazon (heraldic description) so that arms can be stylized differently at a future date without contravening the original grant. What has ensured the survival of heraldry has been its flexibility. If it had not evolved rather quickly out of the framework of feudalism to embrace all types of institutions and all levels of society, chances are that it would no longer exist today.

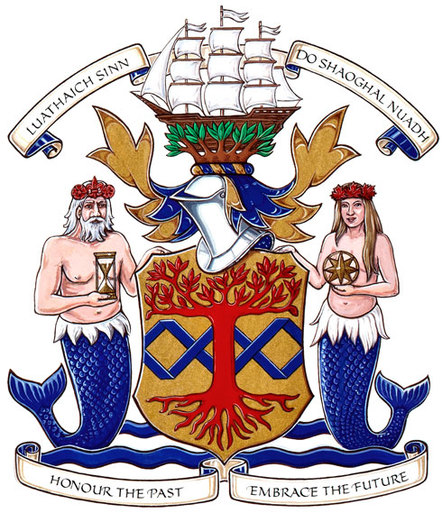

Fig. 4 Merman and mermaid in the arms of Gen-Find Research Associates, Inc., Nanaimo, British Columbia, granted by the Chief Herald of Canada, September 15, 2010, (Vol. V, p. 550). Reproduced by permission of the Canadian Heraldic Authority of Canada © Her Majesty in Right of Canada.

La sirène en héraldique et folklore canadiens (sommaire)

La légende de la sirène, qui remonte à l’Antiquité, s’est répandue dans le monde entier et se ressemble souvent d’une culture à l’autre, aussi bien dans sa représentation physique que psychique. L’article explore les siréniens, qui par leur apparence et comportement, semblent avoir nourri ce mythe: phoque, dugong (vache marine) et lamantin. Il examine l’emploi du mot sirène pour désigner des noms de lieux ou encore des bateaux qui sont liés à l’histoire du pays. La présence de créatures analogues dans les légendes amérindiennes et inuit est abordée brièvement. On y retrouve la description d’une sirène aperçue par Colomb dans le Nouveau-Monde et ensuite des témoignages sur le territoire canadien. L’un d’eux décrit avec beaucoup de détails une créature observée longuement par le capitaine Richard Whitbourne et plusieurs autres marins dans le havre de Saint John’s à Terre-Neuve en 1610. On s’étonne que des navigateurs accoutumés à observer la faune marine soient incapables d’identifier cet être qu’ils voient de près et associent à la légendaire sirène. Une figure étrange combinant un torse avec un visage humain et une queue de poisson se retrouve dans un recueil de dessins nommé Codex Canadensis (p. 59) réalisé pour illustrer l'Histoire naturelle des Indes occidentales du jésuite Louis Nicolas qui séjourna au Canada de 1664 à 1674. L’inscription se lit « Monstre marin tué par les Français sur la rivière de Richelieu en Nouvelle-France ». On peut voir cette curieuse créature sur le site : http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/026014/f1/4726.7.055-v5.jpg (consulté le 13 nov. 2013), mais une fois de plus, il est impossible de dire de quoi il s’agit. Plusieurs armoiries modernes mettent à l’honneur l’ancien mythe de la sirène ou d’êtres similaires comme les deux Simbis qui supportent les armes de la très honorable Michaëlle Jean (fig. 1). On pourra consulter ces concessions dans le registre de l’Autorité héraldique du Canada qui devient de plus en plus disponible en ligne. La concession de sirènes soulève parfois des questions de rectitude politique parce qu’elles apparaissent torse nu en héraldique de sorte que les récipiendaires d’armoiries demandent souvent qu’on évite de mettre l’accent sur certains aspects de leur anatomie. A.V.

La légende de la sirène, qui remonte à l’Antiquité, s’est répandue dans le monde entier et se ressemble souvent d’une culture à l’autre, aussi bien dans sa représentation physique que psychique. L’article explore les siréniens, qui par leur apparence et comportement, semblent avoir nourri ce mythe: phoque, dugong (vache marine) et lamantin. Il examine l’emploi du mot sirène pour désigner des noms de lieux ou encore des bateaux qui sont liés à l’histoire du pays. La présence de créatures analogues dans les légendes amérindiennes et inuit est abordée brièvement. On y retrouve la description d’une sirène aperçue par Colomb dans le Nouveau-Monde et ensuite des témoignages sur le territoire canadien. L’un d’eux décrit avec beaucoup de détails une créature observée longuement par le capitaine Richard Whitbourne et plusieurs autres marins dans le havre de Saint John’s à Terre-Neuve en 1610. On s’étonne que des navigateurs accoutumés à observer la faune marine soient incapables d’identifier cet être qu’ils voient de près et associent à la légendaire sirène. Une figure étrange combinant un torse avec un visage humain et une queue de poisson se retrouve dans un recueil de dessins nommé Codex Canadensis (p. 59) réalisé pour illustrer l'Histoire naturelle des Indes occidentales du jésuite Louis Nicolas qui séjourna au Canada de 1664 à 1674. L’inscription se lit « Monstre marin tué par les Français sur la rivière de Richelieu en Nouvelle-France ». On peut voir cette curieuse créature sur le site : http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/026014/f1/4726.7.055-v5.jpg (consulté le 13 nov. 2013), mais une fois de plus, il est impossible de dire de quoi il s’agit. Plusieurs armoiries modernes mettent à l’honneur l’ancien mythe de la sirène ou d’êtres similaires comme les deux Simbis qui supportent les armes de la très honorable Michaëlle Jean (fig. 1). On pourra consulter ces concessions dans le registre de l’Autorité héraldique du Canada qui devient de plus en plus disponible en ligne. La concession de sirènes soulève parfois des questions de rectitude politique parce qu’elles apparaissent torse nu en héraldique de sorte que les récipiendaires d’armoiries demandent souvent qu’on évite de mettre l’accent sur certains aspects de leur anatomie. A.V.