Heraldic Whimsies

Auguste Vachon, Outaouais Herald Emeritus

Heraldry is generally considered a precise science with specific rules and an art that thrives on simplicity based on the fact that a few clear messages have more visual impact than several complex ones. On the other hand, there is a tendency for many artists to add features to heraldic compositions with the aim of making them more decorative or more dramatic. This is particularly true in the hands of artists with little knowledge of heraldry and a fertile imagination as can be found among designers, architects, sculptors, medalists, seal engravers and cartographers.

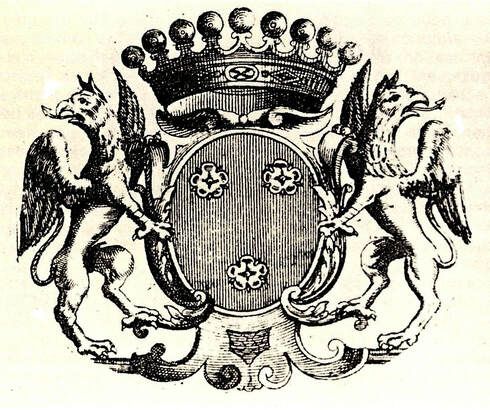

In Great Britain, heraldic authorities dictate that a coat of arms should not include a coronet above an armiger’s rank. Supporters are only included if the armiger belongs to specific categories of persons that are entitled to have their shield held, by animals generally, but sometimes by humans or even objects such as pillars. In the French heraldic system, no control existed for anything exterior to the shield. An individual sometimes had many mottos and could change the one accompanying his armorial bearings whenever a new rendering was made.[1] It was frequent for nobles to make use of a coronet representing a title superior to their own (fig. 1). Commoners with no title also used high-ranking coronets.[2] This applied as well to supporters which would appear in various places although they were not described in legal documents or armorials.[3] For French heraldry, the notion that types of helmets were strictly applicable to varying degrees of nobility was mostly theoretical.[4]

In Great Britain, heraldic authorities dictate that a coat of arms should not include a coronet above an armiger’s rank. Supporters are only included if the armiger belongs to specific categories of persons that are entitled to have their shield held, by animals generally, but sometimes by humans or even objects such as pillars. In the French heraldic system, no control existed for anything exterior to the shield. An individual sometimes had many mottos and could change the one accompanying his armorial bearings whenever a new rendering was made.[1] It was frequent for nobles to make use of a coronet representing a title superior to their own (fig. 1). Commoners with no title also used high-ranking coronets.[2] This applied as well to supporters which would appear in various places although they were not described in legal documents or armorials.[3] For French heraldry, the notion that types of helmets were strictly applicable to varying degrees of nobility was mostly theoretical.[4]

Fig. 1. Arms of Gilles Hocquart, Intendant of New France (1729-1749). The coronet of a count appears above his shield, although he had no such title. From the bookplate of Hocquart in the Paul-André Fournier Collection now at Laval University. Reproduced from Daniel Cogné, “Les armoiries de l’intendant Gilles Hocquart” in Heraldry in Canada / L’Héraldique au Canada (September 1981): 4-9. The same armorial bearings, also with a count’s coronet and griffin supporters, appear on the intendant’s seal: Daniel Cogné, « Les cachets des intendants de la Nouvelle-France » in Heraldry in Canada/L’Héraldique au Canada (June 1986): 11-12. Like so many other French nobles, Hocquart appears to have adopted freely, not just his coronet, but also his supporters. They are not mentioned in the many armorials and legal documents I have consulted.

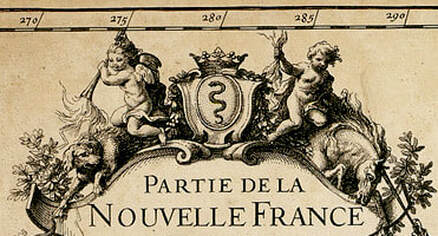

Although supporters were adopted freely in French heraldry, they usually respect the dictates of good heraldry as in figure 1. But there are instances where they become completely fanciful. On a 1685 map by Alexis-Hubert Jaillot showing part of New France, a depiction of the arms of Jean-Baptiste Antoine Colbert, Marquis de Seignelay, French Secretary of State of the Navy, includes two cherubs or winged putti as supporters, one holding a torch and accompanied by a dog, the other holding a thunderbolt and hanging on to a crouching horse. All these additions outside the shield, except for the coronet of a marquis, spring from the cartographer’s imagination (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Arms of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Marquis de Seignelay, on a 1685 map by Alexis Hubert Jaillot, Library and Archives Canada, NMC 6348. See the full map on this site : http://crccf.uottawa.ca/passeport/I/IA1c/IA1c03-1_b.html.

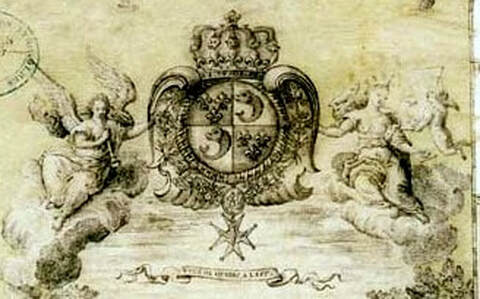

The arms of the Dauphin of France appear on a 1702 map of New France by Jean-Baptiste-Louis Franquelin. The dauphin at that time was Louis of France termed the Grand-Dauphin, eldest son of Louis XIV and dauphin from 1661 to 1711. The shield is held on the left by an angel seated on a cloud and playing a trumpet and, on the right, by an allegorical figure seated on a cloud, wearing a celestial crown (a circlet topped by spikes ending in stars), her left hand pointing to a compass, and being presented a map by a hovering cherub. With music on the left and the scene on the right, the supporters do not just hold the shield; they participate in something not unlike an opera (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Coat of arms of the Dauphin of France on a 1702 map of New France by Jean-Baptiste-Louis Franquelin. The dauphin is Louis of France (1661-1711). The arms are part of a larger cartouche displaying the Town of Quebec and underneath the coming together of the French and First Nations. Cherubs are a favorite aspect of the decorative features of the full map. In the upper left corner, three cherubs hold a mantle topped by the royal crown of France and inscribed with the names of the territories represented. In the upper right corner, five cherubs hold a drape with an inscription explaining that the territories of the native inhabitants are not marked because they remain uncharted. See the original map: http://expositions.bnf.fr/marine/grand/por_233.htm and http://classes.bnf.fr/essentiels/grand/ess_012.htm.

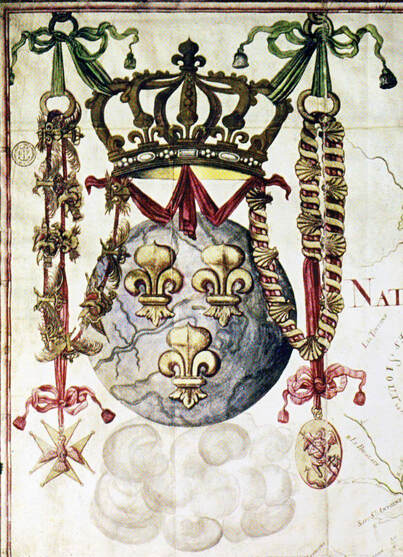

On several occasions, Jean-Baptiste-Louis Franquelin, the “king’s hydrographer at Quebec in Canada,” displays an ebullient imagination in his manner of rendering armorial compositions. One of the most intriguing depictions of the royal arms of France appears on one of his maps of North America drawn in 1688 (fig. 4). A close look reveals how unusual it is. The whole is suspended by green ribbons from two rings attached to the frame of the map. The round shield is itself attached to the royal crown by a red ribbon. Hanging from the two rings by green ribbons is a second set of rings in which are inserted the collars of the king’s orders, the order of the Holy Spirit (ordre du Saint-Esprit) on the left and the order of Saint Michael (ordre de Saint-Michel) on the right. These two collars are normally around the shield. Here they have one end attached to the jewel or badge and the other end attached to the crown. The shield itself with its three gold fleurs-de-lis takes the form of a blue terrestrial globe where the St. Lawrence River, its gulf with some of its tributaries, and part of the coastline are clearly visible. The globe rests upon a cloud.

Fig. 4. Royal arms of France on a 1688 map of North America by Jean-Baptiste-Louis Franquelin. In the lower right of the full map, two cherubs hold the edges of a drape on which appears a view of the Town of Quebec. The Service historique de la Marine, Vincennes, France, holds the original. The Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec and the Library of Congress have copies. See the full map here: http://histoiresdancetres.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/9-Am%C3%A9rique-septentrionale-1688-Franquelin.gif.

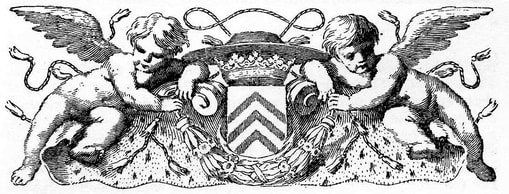

The arms of the sovereigns of France are supported by two angels. One would expect their use to be prohibited in other French coats of arms, but this is not the case. On the seal of Governor Pierre de Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil Cavagnal, two angels support the shield, although no known written documentation confirms his entitlement to such supporters.[5] Cardinal Richelieu’s arms are in most cases depicted without supporters because supporters are rarely included with ecclesiastical arms. While a few renderings include cherubs that are close enough to his shield to be viewed as supporters (fig. 5), in other depictions they are purely decorative.[6]

Fig. 5. Arms of Cardinal Richelieu engraved by Claude Melan, from Arthur Charles Fox-Davies, The Art of Heraldry (London: T.C. & E.C. Jack, 1904): 435. In this image the cherubs are close enough to shield to be viewed as supporters, but in other examples they are purely decorative as on a print in the British Museum which features seven cherubs busying themselves about his shield: https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details/collection_image_gallery.aspx?assetId=491381001&objectId=1459683&partId=1.

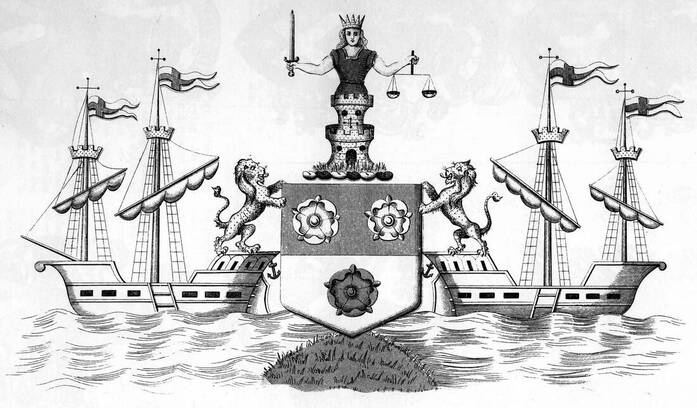

Dramatic and overwrought supporters are not exclusive to the French heraldic system; they are also present in British heraldry. The Town of Southampton, a port city on England’s South Coast, has a very elaborate stand (compartment) for its lion supporters, the whole reflecting its geographical location. Besides the usual grassy mound that normally serves as the compartment, it features two ships on a sea that provide a complex base for the lions holding the shield (fig. 6).

Fig. 6. The achievement of arms of the Town of Southampton, granted 4 August 1575. Note the elaborate platform on which the lions stand. From Arthur Charles Fox-Davies, The Art of Heraldry (London: T.C. & E.C. Jack, 1904), plate LXIV.

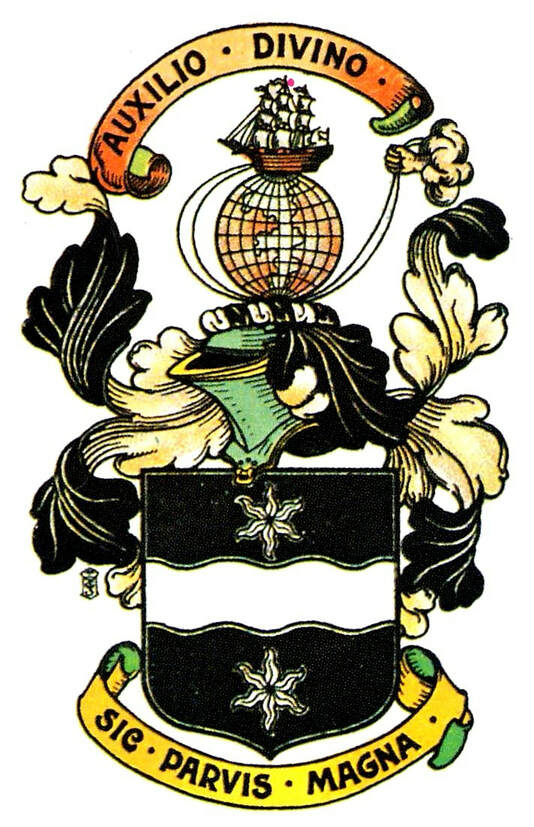

One of the very spectacular heraldic designs involving a ship is the crest of the arms of Sir Francis Drake where the hand of God issuing out of a cloud holds cables pulling his ship around the globe in reference to his circumnavigation of the earth. The motto at the top Auxilio divino (With divine aid) thoroughly reflects the imagery of the crest which expresses the belief that Drake was guided and protected by the hand of God during his signal exploit (fig. 7). The fanciful aspect of the image can be viewed as outlandish when one considers that the crest was originally borne on top of the helmet of a knight riding a horse. Carrying the world on one’s head would present a challenge of nightmarish proportions. Yet this is not really a problem. Lions often appear in crests although a lion or half of one would be much too large for a knight to carry on his helmet, nor could a real polar bear be wielded on a shield, although large animals are legitimate heraldic figures. Many aspects of heraldry have a dreamlike quality. Red, blue, green, or black, or a combination of these colours, are entirely acceptable hues for a lion in an armorial composition, even if no such creatures exist in nature. It is rather a question of good taste and harmony. Here the crest is so overwhelming and dramatic that it draws attention away from the shield which is the most important part of a coat of arms.

Fig. 7. Achievement of arms of Sir Francis Drake granted on 20 June 1581 by Robert Cooke, Clarenceux King of Arms. The hand of God pulls Drake’s ship around the globe. From Arthur Charles Fox-Davies, A Complete Guide to Heraldry (1909), plate VI. See also: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/globe-crests-of-early-navigators.html.

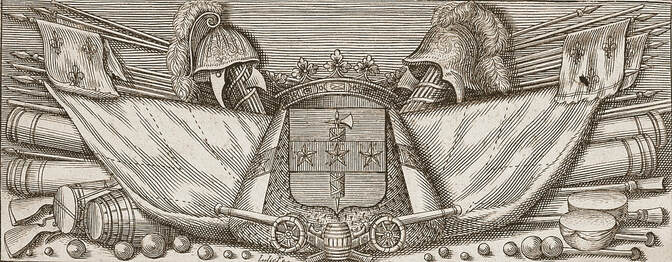

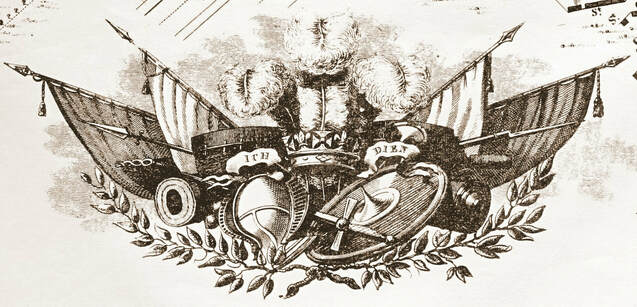

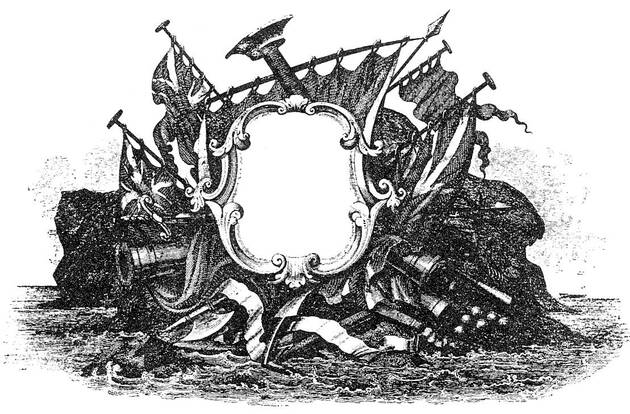

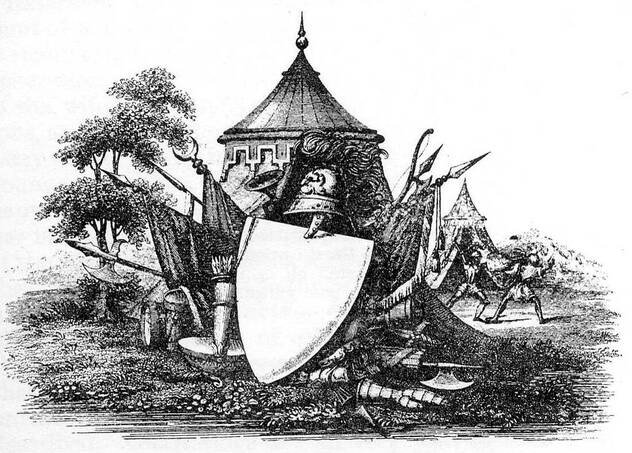

When decorative zeal is given a free hand, panoplies (military trophies) made of such things as flags, weaponry, pieces of armour and drums can appear outside the shield (figs. 8-12). This was done for French as well as English arms (see fig 8 and endnote [7]). In the armorial bearings of Richard White, Earl of Bantry (fig. 9), the panoply is described as “Behind the arms and supporters, military trophies, as flags, cannon, balls, & c.” According to Fox-Davies, the trophy was actually granted, although such displays are usually not mentioned in heraldic descriptions because they reflect the decorative impulse of an artist. Fox-Davies also shows examples of shields in front of elaborate military trophies reproduced from Knight and Rumley’s Heraldry (figs. 11-12). One might think that these trophies represent the spoils of victory, but this is certainly not always the case since flags of the armiger’s own country are sometimes included. In figure 8, the arms of a French minister are depicted with several depictions of the banner of France.

Fig. 8. Arms of Cardinal Jules Mazarin, Chief Minister to the King of France, seventeenth century engraving by Lulié. See original: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8404695v.item.

Fig. 9. Coat of arms of Richard White, Earl of Bantry, Viscount Beerhaven. The motto on the scroll is “The noblest motive is the public good.” From Debrett's Complete Peerage of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and ...., edited by William Courthope, 1838: 596.

Fig. 10. The badge of the Prince of Wales is featured with a dedication to George Augustus Frederick of Hanover, Duke of Cornwall, future King George IV, on a map of Lower Canada by Joseph Bouchette published in 1815 by William Faden of London. See a copy of the map: http://www.davidrumsey.com/maps5170.html.

Fig. 11. A shield in front of a panoply of flags and weapons. From Arthur Charles Fox-Davies, The Art of Heraldry (London: T.C. & E.C. Jack, 1904): 41.

Fig. 12. A shield in front of a panoply of flags, weapons and armour. From Arthur Charles Fox-Davies, The Art of Heraldry (London: T.C. & E.C. Jack, 1904): 41.

In some cases, the space between the base of the shield and the motto scroll serves to include ornamentation. The mantling (or lambrequins) emanating from the top of the shield can itself be highly convoluted (Fig. 13). The compartment (often a grassy mound) on which the supporters stand can provide a space to include a variety of symbolic and decorative elements.[8]

Fig. 13. Bookplate displaying the arms of Sir Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine, granted by the Kings of Arms of England in 1854. Note the convoluted mantling issuing from the top of the helmet and the intricate scrollwork between the base of the shield and the motto ribbon. From Library and Archives Canada.

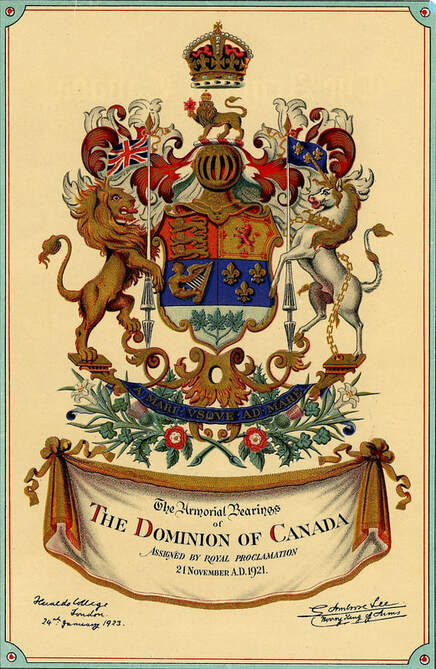

In the 1923 version of the armorial bearings of Canada, the supporters are standing on an elaborate pedestal, which is integrated to the motto scroll and the floral emblems of the founding nations to form a decorative and symbolic whole (fig. 14). Even if Canada’s armorial bearings were granted by royal proclamation, it did not prevent artists from distorting them according to their fancy (fig. 15-16).

Fig. 14. The 1921 arms of Canada with revisions in style introduced in 1923. Illustration from: Department of the Secretary of State of Canada, The Arms of Canada (Ottawa: F.A. Acland Printer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty, 1923).

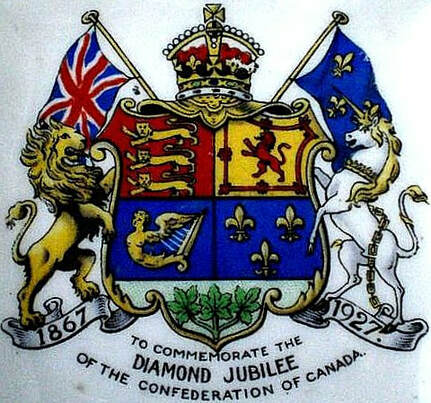

Fig. 15. A distorted version of armorial bearings of Canada reproduced on a number of ceramic pieces marking the Diamond Jubilee of Canada in 1927. In this case the flags, no longer held by the lion and unicorn, are placed in saltire behind the shield. The crest is gone and the crown, which should be above everything, is engulfing a large portion of the helmet. The motto A mari usque ad mare is replaced by dates on the scroll below. On a pin dish by John Aynsley & Son, England, 1927. The earlier shield of the Dominion also underwent many modifications and additions (see: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/dominion-shields.html).

Fig. 16. The strange concoction designed for the Diamond Jubilee of Canada (fig. 15) was picked up by other companies after 1927. The mark in orange on this vase’s bottom reads: “HAND PAINTED/ TRICO/ NAGOYA JAPAN.” Trico is one of the marks of Tashiro Shoten Ltd., of Japan. The colours as well as the reserve with a decorative frame in which the arms appear are reminiscent of German souvenirs created for the Canadian market. Other companies that repeated the same arms without reference to the 1927 Diamond Jubilee are Grimwades (Royal Winton), England and J. Schneider & Co. of Altrohlau, Czechoslovakia. Several other unmarked pieces with the same arms appear to be from Germany.

Remarks

We have seen many examples where various designers and artist have added features to armorial emblems or distorted them with a view to making them more decorative or dramatic. In a coat of arms, the most important component is the shield and what is on it. The content of the shield should itself be kept simple in conformity with the idea that a few clear messages are more striking visually than many complex ones. In placing decorative elements outside the shield, care should be taken that they not become so overwhelming as to monopolize the viewer’s eye. Theatrics outside the shield as in figures 2- 3 and7 tend to do just that. With huge dramatic compartments such as in figure 6 or complicated trophies as in figures 8 to 12, the shield, although in the centre, looses a great deal of its visual impact.

We have seen many examples where various designers and artist have added features to armorial emblems or distorted them with a view to making them more decorative or dramatic. In a coat of arms, the most important component is the shield and what is on it. The content of the shield should itself be kept simple in conformity with the idea that a few clear messages are more striking visually than many complex ones. In placing decorative elements outside the shield, care should be taken that they not become so overwhelming as to monopolize the viewer’s eye. Theatrics outside the shield as in figures 2- 3 and7 tend to do just that. With huge dramatic compartments such as in figure 6 or complicated trophies as in figures 8 to 12, the shield, although in the centre, looses a great deal of its visual impact.

N.B. All the websites mentioned in this article were consulted on 10 February 2019. Figures 15 and 16 are from the Auguste and Paula Vachon collection of Canadian heraldic ceramic, now in the Canadian Museum of History.

Notes

[1] For instance, Cardinal Richelieu had a large number of mottos that appeared here and there at his whim. Auguste Vachon, “Richelieu (1585-1642)” in Heraldry in Canada / L’Héraldique au Canada 21, no. 3 (September 1987): 33-35.

[2] Daniel Cogné, “Les cachets des gouverneurs de la Nouvelle-France” in Heraldry in Canada / L’Héraldique au Canada 22, no. 1 (March 1988): 19

[3] “A complete freedom has always existed in the use of supporters … Often an armiger would adopt new supporters when he changed the die of his seal.” Translation from Michel Pastoureau, Traité d’héraldique (Paris: Picard, 3d ed., 1997): 213. “The adoption of supporters which exhibited no consistency before the sixteenth century was never regulated. … The use of mottos and cries was never subject to specific rules.” Translation from Rémi Mathieu, Le système héraldique français (Paris: J.B. Janin, 1946): 210-211.

[4] “Numerous heraldic treatises and manuals attempt to classify helmets according to their style and to make them correspond to a specific hierarchy. Such classifications are highly theoretical. Moreover they could not have been enforced.” Translation from Ottfried Neubecker, Le grand livre de l’héraldique (Brussels: Elsevier Séquoia, 1977): 148.

[5] See illustrations in Daniel Cogné, “Cachets gouverneurs Nouvelle-France” (see note 2): 17-18.

[6] See other examples here: http://www.dhistoire-et-dart.com/Stella/Stella_cat_Paris-1640_1644_VignettesIR.html). In several depictions the cherubs are clearly decorative. An engraving in the Bibliothèque nationale de France places his shield in front of an impressive trophy of weapons with four cherubs, not acting as supporters, but hovering about and gripping the cords of the cardinal’s hat. The engraving is entitled “DEVISE/ POVR MONSEIGNEVR LE CARDINAL / DE RICHELIEV / Généralissime, Grand Maître, Et Sur-Intendant de la Marine / PELAGI DECVS ADDIDIT ARMIS.” The inscription proposes a motto for Cardinal Richelieu that comes from Marcus Annaeus Lucanus, Civil War: “At Brutus in aequore victor Primus Caesareis pelagi decus addidit armis.” (But Brutus, as the victor on the sea, provided Caesar’s warfare with its first maritime glory.) Basically the motto means “He added maritime glory to military power.” It refers to the fact that Richelieu took important steps to strengthen the French navy and, in 1626, appointed himself Grandmaster, Chief and Superintendant General of Navigation and Commerce.

[7] The arms of France sometimes appear with very intricate panoplies as illustrated in Conrad Swan, Canada Symbols of Sovereignty (Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1977), plate 4.

[8] See: http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1429&ProjectElementID=4776 ― http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=576&ProjectElementID=2023 ―

http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=3040&ProjectElementID=10692.

[1] For instance, Cardinal Richelieu had a large number of mottos that appeared here and there at his whim. Auguste Vachon, “Richelieu (1585-1642)” in Heraldry in Canada / L’Héraldique au Canada 21, no. 3 (September 1987): 33-35.

[2] Daniel Cogné, “Les cachets des gouverneurs de la Nouvelle-France” in Heraldry in Canada / L’Héraldique au Canada 22, no. 1 (March 1988): 19

[3] “A complete freedom has always existed in the use of supporters … Often an armiger would adopt new supporters when he changed the die of his seal.” Translation from Michel Pastoureau, Traité d’héraldique (Paris: Picard, 3d ed., 1997): 213. “The adoption of supporters which exhibited no consistency before the sixteenth century was never regulated. … The use of mottos and cries was never subject to specific rules.” Translation from Rémi Mathieu, Le système héraldique français (Paris: J.B. Janin, 1946): 210-211.

[4] “Numerous heraldic treatises and manuals attempt to classify helmets according to their style and to make them correspond to a specific hierarchy. Such classifications are highly theoretical. Moreover they could not have been enforced.” Translation from Ottfried Neubecker, Le grand livre de l’héraldique (Brussels: Elsevier Séquoia, 1977): 148.

[5] See illustrations in Daniel Cogné, “Cachets gouverneurs Nouvelle-France” (see note 2): 17-18.

[6] See other examples here: http://www.dhistoire-et-dart.com/Stella/Stella_cat_Paris-1640_1644_VignettesIR.html). In several depictions the cherubs are clearly decorative. An engraving in the Bibliothèque nationale de France places his shield in front of an impressive trophy of weapons with four cherubs, not acting as supporters, but hovering about and gripping the cords of the cardinal’s hat. The engraving is entitled “DEVISE/ POVR MONSEIGNEVR LE CARDINAL / DE RICHELIEV / Généralissime, Grand Maître, Et Sur-Intendant de la Marine / PELAGI DECVS ADDIDIT ARMIS.” The inscription proposes a motto for Cardinal Richelieu that comes from Marcus Annaeus Lucanus, Civil War: “At Brutus in aequore victor Primus Caesareis pelagi decus addidit armis.” (But Brutus, as the victor on the sea, provided Caesar’s warfare with its first maritime glory.) Basically the motto means “He added maritime glory to military power.” It refers to the fact that Richelieu took important steps to strengthen the French navy and, in 1626, appointed himself Grandmaster, Chief and Superintendant General of Navigation and Commerce.

[7] The arms of France sometimes appear with very intricate panoplies as illustrated in Conrad Swan, Canada Symbols of Sovereignty (Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1977), plate 4.

[8] See: http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1429&ProjectElementID=4776 ― http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=576&ProjectElementID=2023 ―

http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=3040&ProjectElementID=10692.