The Achievement of Arms of Bordeaux: an Emblem Born in Strife

Auguste Vachon, Outaouais Herald Emeritus

For centuries Guyenne, or Aquitaine, and its capital Bordeaux were prey to the rivalries between France and England. In 1152 Eleanor of Aquitaine married Henry, Duke of Normandy and Count of Anjou, who became King Henry II of England in 1154 and ruled over Guyenne (or Aquitaine) in right of his wife. As a result of a treaty between Louis IX of France and Henry III of England in 1259, English kings held the Duchy of Guyenne as feudatories of the Kings of France. In 1294 war over Guyenne broke out between Philip IV of France and Edward I of England. Though French armies eventually gained the upper hand, Guyenne was returned to England by the Treaty of Paris in 1303 after complex negotiations involving nuptial alliances between the two rival dynasties. As a result, Bordeaux was under French control for a short period from 1294 to 1303. In 1338 Philip VI of France initiated a serious campaign to retake Guyenne, but he was unable to capture Bordeaux and abandoned his efforts in 1340 to concentrate on other fronts. By the Treaty of Brétigny in 1360, the French ceded extensive territories in northwestern France to England and Edward III renounced his claim to the throne of France. But the treaty was soon breached with fighting resuming in 1369. With the Battle of Castillon in 1453, France gained permanent control of the territory.

The arms of Bordeaux evolved over centuries. Arms devoid of fleurs-de-lis with three lions placed above the town hall belfry represented Bordeaux during the English occupation of Guyenne (http://www.musee-aquitaine-bordeaux.fr/en/article/stained-glass-window-arms-bordeaux).[1] After the departure of the English in 1453, the number of lions was reduced from three to one and a semy of fleurs-de-lis was placed in chief (at the top), the first known illustration attesting to this being of 1515.[2] This evolution from three lions to one invalidates the frequent claim that the lion of Bordeaux is a legacy of Eleanor of Aquitaine. Like Bordeaux, the City of Waterford (Port Láirge, Ireland) displayed the three gold lions on red of England in chief of its arms, from the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603) up to 1953 when they were removed as were those of Bordeaux much earlier. Apparently the original Waterford arms did not include lions.[3]

The arms of Bordeaux evolved over centuries. Arms devoid of fleurs-de-lis with three lions placed above the town hall belfry represented Bordeaux during the English occupation of Guyenne (http://www.musee-aquitaine-bordeaux.fr/en/article/stained-glass-window-arms-bordeaux).[1] After the departure of the English in 1453, the number of lions was reduced from three to one and a semy of fleurs-de-lis was placed in chief (at the top), the first known illustration attesting to this being of 1515.[2] This evolution from three lions to one invalidates the frequent claim that the lion of Bordeaux is a legacy of Eleanor of Aquitaine. Like Bordeaux, the City of Waterford (Port Láirge, Ireland) displayed the three gold lions on red of England in chief of its arms, from the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603) up to 1953 when they were removed as were those of Bordeaux much earlier. Apparently the original Waterford arms did not include lions.[3]

Heraldic Description (Blazon)

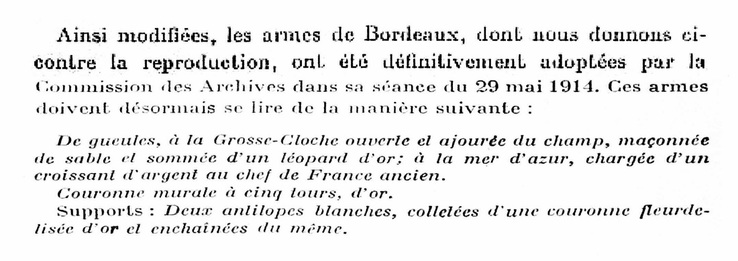

In 1914 the Publication Committee of the Municipal Archives of Bordeaux met to establish officially the heraldic description of the arms of the city. It submitted its final description on 29 May 1914. The French text announcing this along with the blazon is seen in figure 1.

In 1914 the Publication Committee of the Municipal Archives of Bordeaux met to establish officially the heraldic description of the arms of the city. It submitted its final description on 29 May 1914. The French text announcing this along with the blazon is seen in figure 1.

Fig. 1. French text announcing the blazon adopted by the Publication Committee of the Municipal Archives of Bordeaux. From Meaudre de La Pouyade, “Les armoiries de Bordeaux (supplément)” in Revue historique de Bordeaux et du département de la Gironde, 19th year, no. 1 (Jan.-Feb. 1916), pp.47-48.

Unfortunately the blazon provided by the Publication Committee in 1914 contained awkward wording and several ambiguities. For instance, the tincture of the belfry was not specified and its stones are described as being outlined in black which is only normal. It would be necessary to specify the outline if it were of an unusual colour such as red, blue or green. Another flaw in the description is that the reader has to guess where the sea is situated relative to the other charges. The word sommée used in connection with the belfry and the lion means that the lion is supported by the belfry. Although this is the case in some depictions, it may well be a situation where the shield has become a little crowded. In four sixteenth century depictions, a horizontal line is inserted between the lion and the belfry clearly indicating that, in the mind of the artists, the lion is independent of the belfry.[4]

Another misleading aspect concerns the supporters that are described as white antelopes. This sounds like a species of antelope, which is not the case since it was difficult from early depictions to determine what animal was intended, let alone the specific species. Since white is not a heraldic colour, the tincture designation should be Argent. If the species had been intended, the tincture would still have to be specified. An analogous example will make this clear. If a shield has two American black bears as supporters, this only indicates the species, not the tincture. If indeed they are coloured black, the word proper (natural colour) or sable has to be added because they could be depicted in any tincture or pattern of tinctures that heraldry provides. For instance, it would be entirely within the realm of heraldic propriety, though a little unusual, for the black bears to be depicted barry-wavy Argent and Gules.

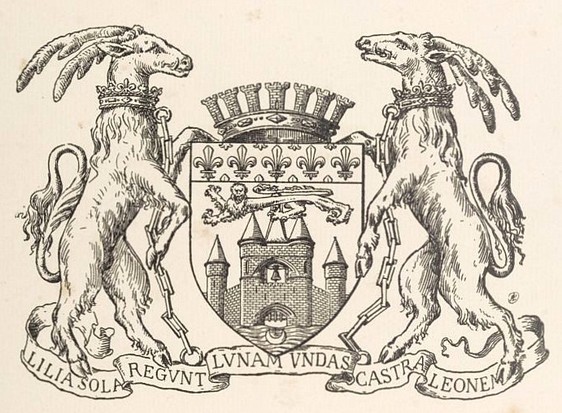

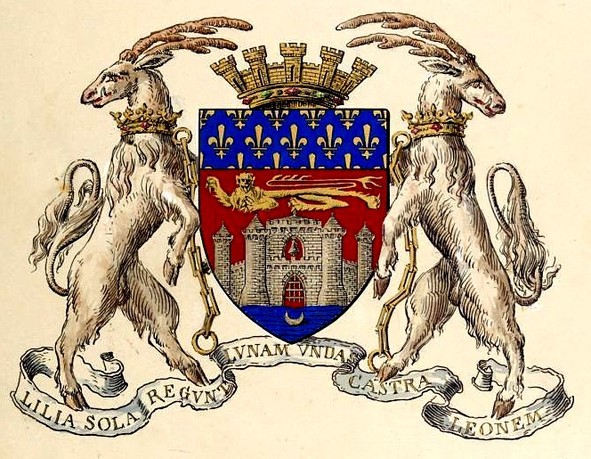

In some depictions, the antelopes are shown as reguardant, that is looking directly backwards (compare figures 3 and 4). This seems to be a recent interpretation since sixteenth century engravings of the arms show the antelopes looking straight ahead.[5] The antelopes are likely derived from the supporters of the arms of Henry VI in which they look forward not backward (see comment with figure 3 and endnote 5). In some depictions, the mural crown has five turrets while in others it has seven (compare figs. 3 & 4). Unless the number of turrets is linked to a specific symbolism, it is often better to avoid quantifying this in the description and to leave this type of detail to artists.

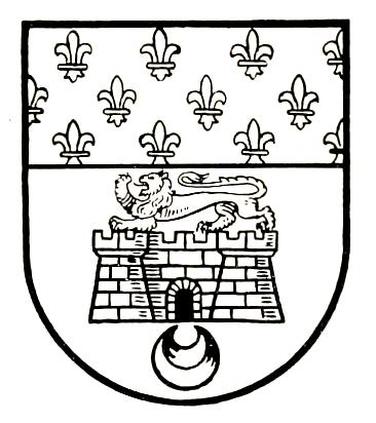

The arms of Bordeaux have been described in various ways in the past, and understandably so, since their exact colours and components were not clearly specified. This has continued into the twentieth century. In 1915, for instance, Fox-Davies offers the following blazon Gules, on battlements of a gateway argent, a lion passant or, in base a crescent of the second, a chief azure, semé-de-lis (fig. 2).[6] In this description, three discrepancies are immediately apparent. The lion is passant (looking straight ahead) rather than being passant guardant (looking at the spectator) and the gateway should be a specific monument, namely the town hall belfry called Grosse Cloche. The sea in base is no longer there.

Another misleading aspect concerns the supporters that are described as white antelopes. This sounds like a species of antelope, which is not the case since it was difficult from early depictions to determine what animal was intended, let alone the specific species. Since white is not a heraldic colour, the tincture designation should be Argent. If the species had been intended, the tincture would still have to be specified. An analogous example will make this clear. If a shield has two American black bears as supporters, this only indicates the species, not the tincture. If indeed they are coloured black, the word proper (natural colour) or sable has to be added because they could be depicted in any tincture or pattern of tinctures that heraldry provides. For instance, it would be entirely within the realm of heraldic propriety, though a little unusual, for the black bears to be depicted barry-wavy Argent and Gules.

In some depictions, the antelopes are shown as reguardant, that is looking directly backwards (compare figures 3 and 4). This seems to be a recent interpretation since sixteenth century engravings of the arms show the antelopes looking straight ahead.[5] The antelopes are likely derived from the supporters of the arms of Henry VI in which they look forward not backward (see comment with figure 3 and endnote 5). In some depictions, the mural crown has five turrets while in others it has seven (compare figs. 3 & 4). Unless the number of turrets is linked to a specific symbolism, it is often better to avoid quantifying this in the description and to leave this type of detail to artists.

The arms of Bordeaux have been described in various ways in the past, and understandably so, since their exact colours and components were not clearly specified. This has continued into the twentieth century. In 1915, for instance, Fox-Davies offers the following blazon Gules, on battlements of a gateway argent, a lion passant or, in base a crescent of the second, a chief azure, semé-de-lis (fig. 2).[6] In this description, three discrepancies are immediately apparent. The lion is passant (looking straight ahead) rather than being passant guardant (looking at the spectator) and the gateway should be a specific monument, namely the town hall belfry called Grosse Cloche. The sea in base is no longer there.

Fig. 2. Arms of Bordeaux from Fox-Davies, The Book of Public Arms (1915), p. 95.

In the description that follows, I have attempted to clarify several uncertainties found in previous blazons of Bordeaux by looking at coloured illustrations and the wording in Lapouyade’s own works, but at the same time making sure that nothing was missing or ambiguous. It is important to realize that a tincture (colour or metal) in English blazonry applies to all the preceding charges. For instance in the blazon that follows, Argent is not mentioned in connection with the crescent because it is specified later with the belfry and applies to both figures.

Arms - Issuant in base a sea Azure charged with a crescent, thereon the town hall belfry called Grosse Cloche Argent ports and windows Gules, in chief a lion passant guardant Or, a chief Azure semy of fleurs-de-lis Or;

Crown - A turreted mural crown Or;

Supporters- Two antelopes Argent each collared with a crown flory fitted with a chain Or.

Arms - Issuant in base a sea Azure charged with a crescent, thereon the town hall belfry called Grosse Cloche Argent ports and windows Gules, in chief a lion passant guardant Or, a chief Azure semy of fleurs-de-lis Or;

Crown - A turreted mural crown Or;

Supporters- Two antelopes Argent each collared with a crown flory fitted with a chain Or.

Fig. 3. In this rendering, the antelopes are looking to the front. This seems the correct interpretation since they were depicted as looking forward in engravings of the sixteenth century (see endnotes 4-5) as well as in the supporters of Henry VI from which they are apparently derived, see https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Henry_VI_of_England_(1422-1471).svg. Illustration from the title page of Meaudre de Lapouyade, Armoiries de Bordeaux (1913), see http://1886.u-bordeaux-montaigne.fr/viewer/show/3961#page/n4/mode/1up.

Fig. 4. The full achievement of arms of Bordeaux. In this depiction the antelopes are reguardant, that is looking to the back, which seems a recent development, see the comment with figure 3. Illustration from the volume of Meaudre de Lapouyade, Armoiries de Bordeaux (1913) at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, at http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k96396800/f117.image. This particular volume is bound with added material that is not found in the regular edition, including this illustration.

Symbolism

Arms – The town hall belfry, popularly called Grosse Cloche, is a historical monument specific to the City of Bordeaux. The sea represents the waves of the Garonne formerly called “the sea.” The crescent refers to the shape of the harbour of Bordeaux named Port of the Moon (Portus Lunae), a designation going back to Antiquity according to De Lapouyade. The crescent was already present in a seal of the city dated 1297.[7] The lion passant guardant, as we have seen, comes from the arms of England. The chief, whether semy of fleurs-de-lis (France ancient) or with only three fleurs-de-lis (France modern), was granted as a special favour to the bonnes villes de France, literally good cities of France. The royal chief meant that the cities benefited from special privileges and the protection of the sovereign. Some other French cities with a France ancient chief are Amiens, Paris, Reims, and Toulouse. Examples of cities with a France modern chief are Limoges, Lyon, Orléans, La Rochelle, and Rouen.

Crown - A mural crown is specific to a city. The battlements may be merlons and crenels or, at times, turrets as in the arms of Bordeaux, but also Amiens, Falaise, Le Havre, Lyon, Marseille, Nantes, Paris, Rouen, Saint-Lo, Saumur, Vannes, and many others.

Supporters - The two antelopes are almost certainly of English origin. The practice of placing a crown about the neck of supporters, in this case a crown flory, with a chain attached thereto is typical of English heraldy. The antelopes are apparently lifted from the arms of Henry VI (1422-1461) of the House of Lancaster who had the same white (argent) antelopes as supporters to his shield.[8] His two Lancastrian predecessors, Henry IV and Henry V, coupled a gold lion with a white antelope.

Motto - Lilia sola regunt lunam undas castra leonem means “Fleurs-de-lis alone rule over the moon, the waves, the castle, and the lion.” Though it is a little long, the motto explains clearly why the lion was kept on the shield. Not only is it part of the history of the city, but it patently illustrates a change of regime where the lions are no longer dominant, this position now being held on the shield by fleurs-de-lis. A similar situation occurred in the Canadian Province of Quebec. The shield granted the province in 1868 had two blue fleurs-de-lis on gold at the top, a lion in centre, and a sprig of maple in base. In 1939 the province changed the chief to reflect the original French arms, namely three gold fleurs-de-lis on blue. This emphasized the origins of the majority of the inhabitants of the province, but the lion was kept, which seems reasonable given that it represents a large segment of the province’s history.

Arms – The town hall belfry, popularly called Grosse Cloche, is a historical monument specific to the City of Bordeaux. The sea represents the waves of the Garonne formerly called “the sea.” The crescent refers to the shape of the harbour of Bordeaux named Port of the Moon (Portus Lunae), a designation going back to Antiquity according to De Lapouyade. The crescent was already present in a seal of the city dated 1297.[7] The lion passant guardant, as we have seen, comes from the arms of England. The chief, whether semy of fleurs-de-lis (France ancient) or with only three fleurs-de-lis (France modern), was granted as a special favour to the bonnes villes de France, literally good cities of France. The royal chief meant that the cities benefited from special privileges and the protection of the sovereign. Some other French cities with a France ancient chief are Amiens, Paris, Reims, and Toulouse. Examples of cities with a France modern chief are Limoges, Lyon, Orléans, La Rochelle, and Rouen.

Crown - A mural crown is specific to a city. The battlements may be merlons and crenels or, at times, turrets as in the arms of Bordeaux, but also Amiens, Falaise, Le Havre, Lyon, Marseille, Nantes, Paris, Rouen, Saint-Lo, Saumur, Vannes, and many others.

Supporters - The two antelopes are almost certainly of English origin. The practice of placing a crown about the neck of supporters, in this case a crown flory, with a chain attached thereto is typical of English heraldy. The antelopes are apparently lifted from the arms of Henry VI (1422-1461) of the House of Lancaster who had the same white (argent) antelopes as supporters to his shield.[8] His two Lancastrian predecessors, Henry IV and Henry V, coupled a gold lion with a white antelope.

Motto - Lilia sola regunt lunam undas castra leonem means “Fleurs-de-lis alone rule over the moon, the waves, the castle, and the lion.” Though it is a little long, the motto explains clearly why the lion was kept on the shield. Not only is it part of the history of the city, but it patently illustrates a change of regime where the lions are no longer dominant, this position now being held on the shield by fleurs-de-lis. A similar situation occurred in the Canadian Province of Quebec. The shield granted the province in 1868 had two blue fleurs-de-lis on gold at the top, a lion in centre, and a sprig of maple in base. In 1939 the province changed the chief to reflect the original French arms, namely three gold fleurs-de-lis on blue. This emphasized the origins of the majority of the inhabitants of the province, but the lion was kept, which seems reasonable given that it represents a large segment of the province’s history.

***

One question concerning the arms of Bordeaux remains unclear. Did the city have arms with fleurs-de-lis prior to the permanent acquisition of Guyenne by France in 1453? This is unlikely since Guyenne was under English rule most of the time from 1152 to 1453. Moreover civic armorial bearings began appearing in France in the thirteenth century only, not prior the marriage of the future Henry II to Eleanor of Aquitaine in 1152 [9]. Furthermore, as we have seen, the supporters of the shield of Bordeaux are apparently derived from those of Henry VI, which points to an English origin of the achievement of arms as a whole (fig. 3).

In some recent renderings, the chief of the arms of Bordeaux, usually strewn with fleurs-de-lis, is converted to France modern, namely three gold fleurs-de-lis on blue, perhaps to introduce a touch of modernity. Modifications of this type happen with both freely adopted and registered arms, but when emblems are properly recorded by a state institution or some other well recognized body, it is possible to go back to the original description and rendering to eliminate any uncertainty.

Further reading – This article was inspired by a previous article, “Adding and Subtracting Lions” which touches upon the origins of the single lion of Guyenne.

Websites

All the websites cited in this article were consulted on 15 June 2016.

Notes

[1] Meaudre de Lapouyade, Les armoiries de Bordeaux (Bordeaux : Imprimerie Gounouilhou, 1913), pp. 14-15, 17-18 and plate III.

[2] Ibid., pp. 20-21.

[3] See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Waterford_coa.png. Some authors imply that the arms of Waterford go back to King John who granted the city its charter on 3 July 1205: Jiří Louda, European Civic Coats of Arms (London: Paul Hamlyn, 1966), pp. 206-07. This seems very early for civic arms. The complete achievement of arms of Waterford (including the lions in chief) crest, supporters and motto are found in Arthur-Charles Fox-Davies, The Book of Public Arms (London: T. C. & E. C. Jack, 1915), pp. 834-35. Fox-Davies notes their existence in 1613.

[4] Meaudre de Lapouyade, Armoiries de Bordeaux (1913), pp. 23-25.

[5] Ibid., pp. 21, 23-25.

[6] Arthur-Charles Fox-Davies, The Book of Public Arms, p. 94.

[7] Meaudre de Lapouyade, Armoiries de Bordeaux (1913), p. 6, plate 1, no. 2 and p. 14; R. Dion “Commentaire des armoiries de la ville de Bordeaux” (Communication présentée le 22 octobre 1949 au groupe de géographie historique et d'histoire de la géographie de l'A.G.F.): http://www.persee.fr/doc/bagf_0004-5322_1949_num_26_204_7293.

[8] Meaudre de Lapouyade, Armoiries de Bordeaux (1913), pp. 27-28.

[9] Rémi Mathieu, Le système héraldique français (Paris: J.B. Janin, 1946), pp. 34-36.

In some recent renderings, the chief of the arms of Bordeaux, usually strewn with fleurs-de-lis, is converted to France modern, namely three gold fleurs-de-lis on blue, perhaps to introduce a touch of modernity. Modifications of this type happen with both freely adopted and registered arms, but when emblems are properly recorded by a state institution or some other well recognized body, it is possible to go back to the original description and rendering to eliminate any uncertainty.

Further reading – This article was inspired by a previous article, “Adding and Subtracting Lions” which touches upon the origins of the single lion of Guyenne.

Websites

All the websites cited in this article were consulted on 15 June 2016.

Notes

[1] Meaudre de Lapouyade, Les armoiries de Bordeaux (Bordeaux : Imprimerie Gounouilhou, 1913), pp. 14-15, 17-18 and plate III.

[2] Ibid., pp. 20-21.

[3] See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Waterford_coa.png. Some authors imply that the arms of Waterford go back to King John who granted the city its charter on 3 July 1205: Jiří Louda, European Civic Coats of Arms (London: Paul Hamlyn, 1966), pp. 206-07. This seems very early for civic arms. The complete achievement of arms of Waterford (including the lions in chief) crest, supporters and motto are found in Arthur-Charles Fox-Davies, The Book of Public Arms (London: T. C. & E. C. Jack, 1915), pp. 834-35. Fox-Davies notes their existence in 1613.

[4] Meaudre de Lapouyade, Armoiries de Bordeaux (1913), pp. 23-25.

[5] Ibid., pp. 21, 23-25.

[6] Arthur-Charles Fox-Davies, The Book of Public Arms, p. 94.

[7] Meaudre de Lapouyade, Armoiries de Bordeaux (1913), p. 6, plate 1, no. 2 and p. 14; R. Dion “Commentaire des armoiries de la ville de Bordeaux” (Communication présentée le 22 octobre 1949 au groupe de géographie historique et d'histoire de la géographie de l'A.G.F.): http://www.persee.fr/doc/bagf_0004-5322_1949_num_26_204_7293.

[8] Meaudre de Lapouyade, Armoiries de Bordeaux (1913), pp. 27-28.

[9] Rémi Mathieu, Le système héraldique français (Paris: J.B. Janin, 1946), pp. 34-36.