Canadian Civic Arms on Ceramics

By Auguste Vachon, Outaouais Herald Emeritus

Terminology

Both heraldry and ceramics have their own specialized terminology. The reader who is not familiar with these fields may wish to read the appendix which defines some of the most basic terms.

Both heraldry and ceramics have their own specialized terminology. The reader who is not familiar with these fields may wish to read the appendix which defines some of the most basic terms.

References

Howard M. Chapin, “Canadian Municipal Arms” in The Canadian Historical Review, vol. 18, no. 3 (Sept. 1937) is frequently quoted. He is referred to by surname only, without adding endnotes with page numbers given that his compilation arranges the municipalities in alphabetical order, making them easy to find. Many sections contain links to the Public Register of Arms, Flags and Badges of Canada of the Canadian Heraldic Authority. Readers are encouraged to consult this original source which usually presents an illustration, a blazon (heraldic description) and, where possible, the symbolism. All the websites referred to were consulted on 6 July 2022.

Howard M. Chapin, “Canadian Municipal Arms” in The Canadian Historical Review, vol. 18, no. 3 (Sept. 1937) is frequently quoted. He is referred to by surname only, without adding endnotes with page numbers given that his compilation arranges the municipalities in alphabetical order, making them easy to find. Many sections contain links to the Public Register of Arms, Flags and Badges of Canada of the Canadian Heraldic Authority. Readers are encouraged to consult this original source which usually presents an illustration, a blazon (heraldic description) and, where possible, the symbolism. All the websites referred to were consulted on 6 July 2022.

Picture sources

The ceramic pieces were collected by my wife Paula and I and donated to the Canadian Museum of History in 2011. Figures 60 and 112 are more recent acquisitions. Unless otherwise stated, the heraldic postcards are part of another of our collections. Figures 16-17, 26, 33 are colourized black and white prints.

The ceramic pieces were collected by my wife Paula and I and donated to the Canadian Museum of History in 2011. Figures 60 and 112 are more recent acquisitions. Unless otherwise stated, the heraldic postcards are part of another of our collections. Figures 16-17, 26, 33 are colourized black and white prints.

Part I British Ceramics

Newfoundland and Labrador

Saint John’s

Chapin’s armorial does not include St. John’s because Newfoundland had not yet joined Canada in 1937. In figures 1 to 3, the inscription YE MATTHEW 24TH JUNE MCCCCXCVII on a band across the shield, just below the chief (top part), refers to the arrival of John Cabot (Giovanni Caboto) in Newfoundland aboard his ship the Matthew on St. John the Baptist’s Day, 24 June 1497. [1] The landfall of the ship is depicted at the top while the main part, with the Paschal Lamb and scallop shells, refers to the baptism of Christ by St. John the Baptist (fig. 6). A comparison among figures 1, 2 and 3 reveals discrepancies in the colours of the field, namely red, blue and white respectively. In figure 1, the lamb is Or (gold or yellow); in figure 2, it is Argent (white or silver). The most plausible colour is red which is seen in other ceramic souvenirs and has been retained for the granted achievement of arms in which the lamb and shells become white (figs. 4-5).

Chapin’s armorial does not include St. John’s because Newfoundland had not yet joined Canada in 1937. In figures 1 to 3, the inscription YE MATTHEW 24TH JUNE MCCCCXCVII on a band across the shield, just below the chief (top part), refers to the arrival of John Cabot (Giovanni Caboto) in Newfoundland aboard his ship the Matthew on St. John the Baptist’s Day, 24 June 1497. [1] The landfall of the ship is depicted at the top while the main part, with the Paschal Lamb and scallop shells, refers to the baptism of Christ by St. John the Baptist (fig. 6). A comparison among figures 1, 2 and 3 reveals discrepancies in the colours of the field, namely red, blue and white respectively. In figure 1, the lamb is Or (gold or yellow); in figure 2, it is Argent (white or silver). The most plausible colour is red which is seen in other ceramic souvenirs and has been retained for the granted achievement of arms in which the lamb and shells become white (figs. 4-5).

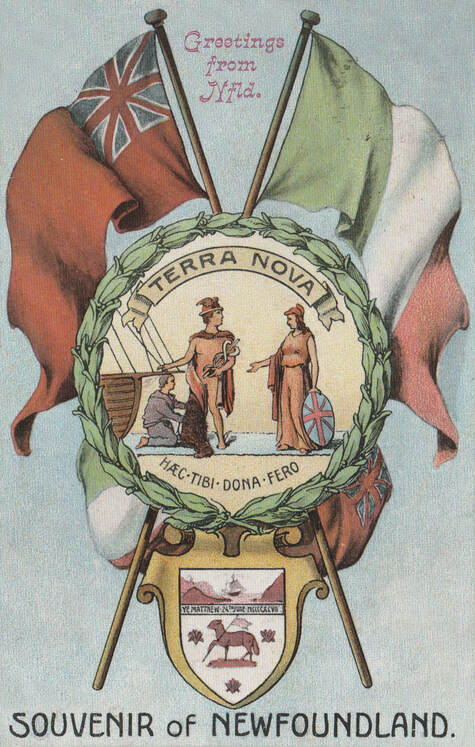

The postcard (fig. 3) features the arms of St. John’s at the bottom and, in the centre, the badge of Newfoundland which derives from the first known impression of its Great Seal dating from 1827. [2] Above on the left, appears the Red Ensign of the British Merchant Marine which was adopted in 1904 by merchant ships of the island with the badge in the fly. The flag on the right is called the “Pink, White and Green”, which was popularly endorsed by Newfoundlanders in the nineteenth century and became the object of an “unofficial ‘national anthem’ ”. [3] The postcard shows the flag colours in reverse, namely as green white and pink.

Fig. 3. Postcard by Ayre & Sons of St. John’s, Newfoundland. A printed inscription on the back reads: “With Kindest Thoughts and Hearty Good Wishes for a Truly Happy Christmas.” The postage stamp was issued in Sept. 1908. Photo courtesy of Michael Smith from his collection of Canadian postcards.

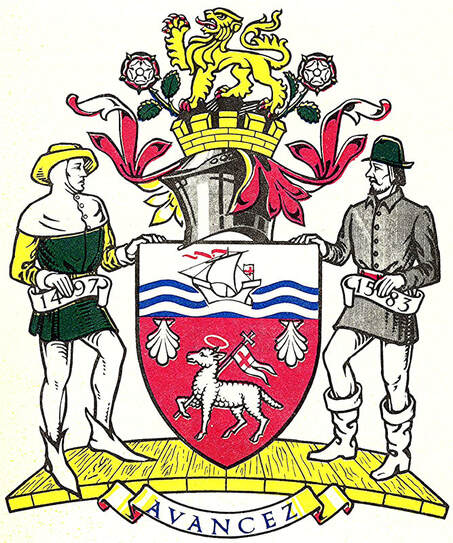

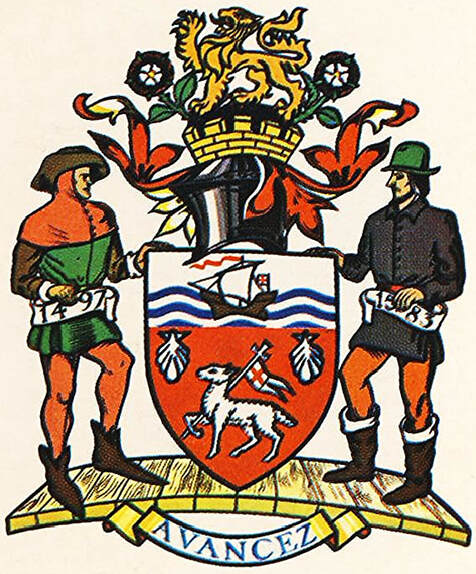

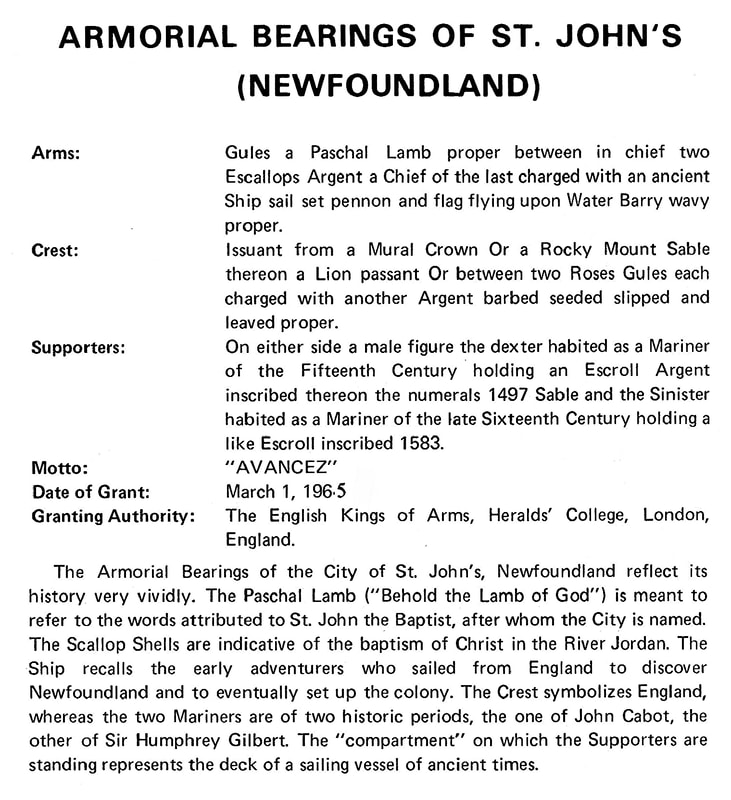

On 1 March 1965, the City of St. John was granted armorial bearings by the English Kings of arms, in which many elements of the original shield were retained. In Beddoe’s Canadian Heraldry, (fig. 5), the garments of the supporters are coloured differently from figure 4, which is acceptable since the blazon specifies attires of a period without indicating colours. In the version recorded in the Public Register of Arms, Flags and Badges of Canada (15 March 2005), there is no helmet above the shield and the supporters are not standing on a sailing vessel deck, two features that are not mentioned in the blazon, see figure 6 and: https://www.gg.ca/en/heraldry/public-register/project/454.

Fig. 4. Armorial bearings of the City of St. John’s granted by the English Kings of arms on 1 March 1965. From Heraldry in Canada (September 1974), p. 2.

Fig. 5. The same supporters as figure 4 with different colouration, from Beddoe’s Canadian Heraldry, p. 94.

Fig. 6. From Heraldry in Canada (September 1974), p. 3.

Nova Scotia

Halifax

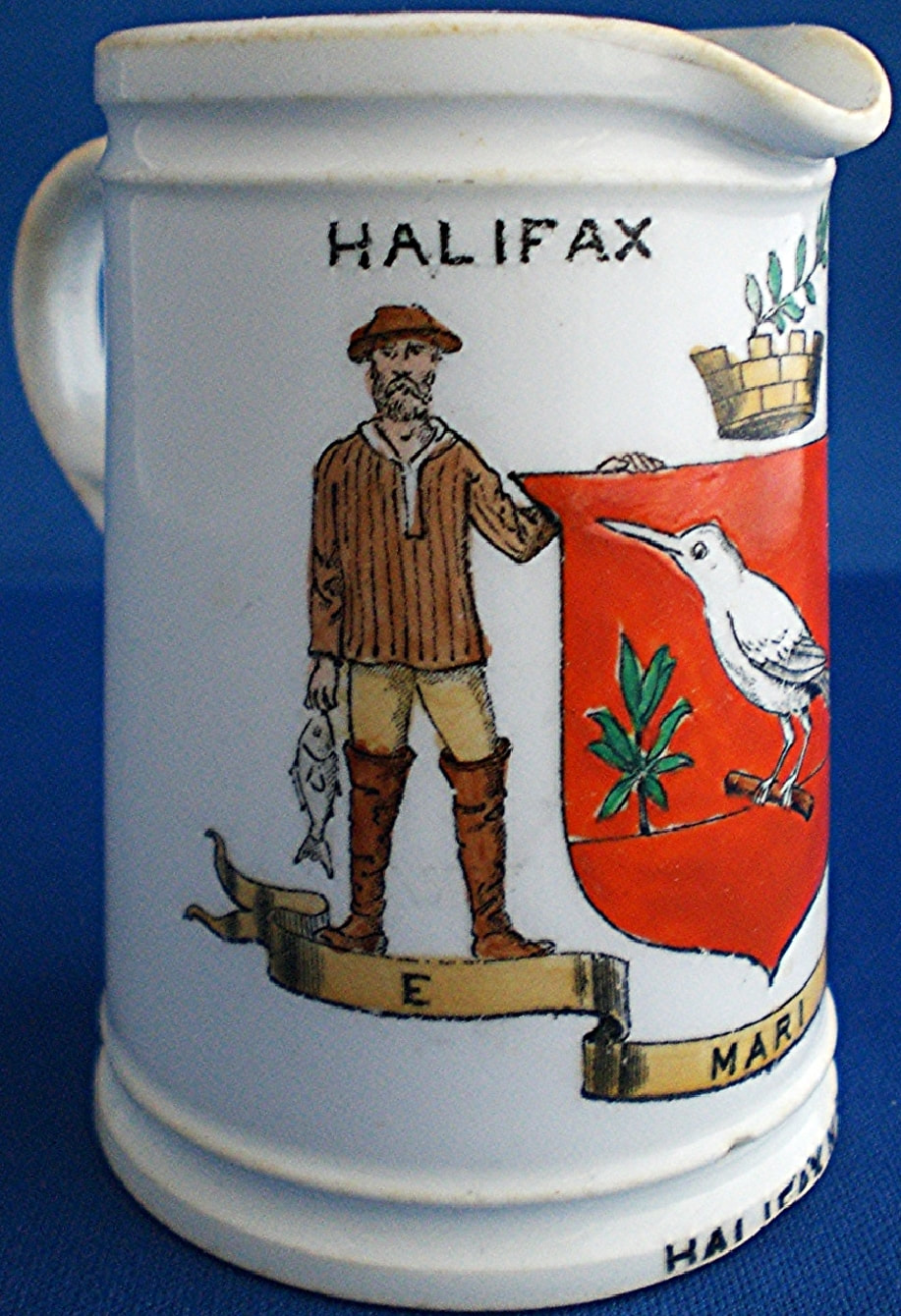

Chapin blazons the arms of Halifax as follows: “Azure perched on a rock sable a kingfisher argent. Crest: Out of a mural crown, mayflowers in bloom. Motto: ‘E mari merces’. Supporters: Dexter a British naval sailor, sinister a deep-sea fisherman with a cod-fish hanging from his right hand.” He further comments: “Sometimes the kingfisher and the rock are or [gold] and sometimes the rock is shown issuant from the sea proper. / John Woodward in Notes and queries, Aug. 7, 1880, gives the arms of Halifax as ‘Or, on a mount in base a blue jay ppr.’ ”. [4]

The old arms of Halifax were a favorite of English ceramic manufacturers including a blue and white jasper version by Wedgwood. Two brothers are mentioned as their creators in 1860, James Cogswell and his brother Charles, a medical doctor. Figure 7a-c with a red field, white bird on a wooden perch and a green plant added is another variant, but the red shield is not unique (fig. 8). Figure 7 presents another interesting feature in that the dexter supporter is the fisherman and the sailor the sinister one, which usually was the reverse at the time. The motto E Mari Merces (Wealth from the sea) remains constant. [5]

Chapin blazons the arms of Halifax as follows: “Azure perched on a rock sable a kingfisher argent. Crest: Out of a mural crown, mayflowers in bloom. Motto: ‘E mari merces’. Supporters: Dexter a British naval sailor, sinister a deep-sea fisherman with a cod-fish hanging from his right hand.” He further comments: “Sometimes the kingfisher and the rock are or [gold] and sometimes the rock is shown issuant from the sea proper. / John Woodward in Notes and queries, Aug. 7, 1880, gives the arms of Halifax as ‘Or, on a mount in base a blue jay ppr.’ ”. [4]

The old arms of Halifax were a favorite of English ceramic manufacturers including a blue and white jasper version by Wedgwood. Two brothers are mentioned as their creators in 1860, James Cogswell and his brother Charles, a medical doctor. Figure 7a-c with a red field, white bird on a wooden perch and a green plant added is another variant, but the red shield is not unique (fig. 8). Figure 7 presents another interesting feature in that the dexter supporter is the fisherman and the sailor the sinister one, which usually was the reverse at the time. The motto E Mari Merces (Wealth from the sea) remains constant. [5]

Fig. 7a-c. Pottery creamer for Halifax Hotel, by The Foley China (Wileman & Co.), c. 1901.

The embossed version in figure 8 shows horizontal lines across the shield which normally denote blue and yet the shield is coloured red. The blue colour of both the sailor and fisherman and the red fish seem somewhat fanciful as does the gold colour of the mayflower rising from the mural crown in the crest. These colours were applied by hand and obviously were sometimes subject to the whims of colourists. In other depictions on MacFarlane postcards with the same arms, the shield is coloured sometimes red, sometimes blue: https://vintagepostcards.ca/Publishers/Canadian/MacFarlane/MacFarlaneViewCards/index.html.

Fig. 8. On a postcard of City Hall, Halifax, by W.G. MacFarlane, Publisher, Toronto. The red of the field is contradicted by the horizontal lines across the shield which indicate blue in heraldry (Azure).

In figures 9 and 10, the shield is blue and the content is essentially the same in both, although the supporters are rendered somewhat differently. Figure 9 is by W.H. Goss, the famous manufacturer of miniature armorial souvenirs. The Goss mark, shown with figure 9b, is a goshawk on a wreath which was also featured “charged on the breast with a bomb fired” in the crest of the family coat of arms designed by William Henry Goss’ eldest son, Adolphus (1853 - 1934). [6] In the Goss mark, the bomb is removed and the bird wears a coronet which has been described as “a falcon rising, ducally gorged” and linked to the Falcon Works where the firm moved around 1870. [7]

Fig. 9a-b. Ivory porcelain bowl by W.H. Goss c. 1905. The shield on this piece is blue. The orange figure under the goshawk is a decorator’s mark.

Fig. 10 a-b. Cup and saucer produced by Royal Grafton (A.B. Jones & Sons Ltd.) for the bicentennial of Halifax 1749-1949.

The numerous discrepancies in the depictions of Halifax’s emblem appearing on the memorabilia created to celebrate de city’s bicentenary in 1949 annoyed the municipal solicitor Carl P. Bethune who decided to impose uniformity in future depictions. The city council authorized him to prepare an ordinance to control the design and use of the arms. The ordinance, approved by the minister of Municipal Affairs on 22 October 1964, blazons the arms as follows: “Azure a crested Kingfisher Or, Crest: out of a mural coronet Or a sprig of mayflowers in bloom proper. Supporters: dexter, a deep-sea fisherman with a codfish dependant from his dexter hand; sinister, a naval seaman, all proper. Motto: E Mari Merces.” [8] In the grant by the Chief Herald of Canada, on 1 July 1992, the supporters stand on a grassy mound: https://www.gg.ca/en/heraldry/public-register/project/1591.

Prince Edward Island

I have not found any municipal arms on ceramics for this province.

New Brunswick

St. John

Chapin describes the armorial bearings of Saint John thus: “Quarterly (1) gules a barrel between four fish, in chief a fish, all or; (2) azure on a champagne a row of trees graduated in height and in chief a sun in splendour or; (3) azure a ship or at sea barry undy or and azure; (4) gules two beavers in pale or. The number of trees varies from four to seven and sometimes the highest is at dexter and sometimes at sinister. Crest: A crown. Motto; ‘O fortunati quorum jam moenia surgent’. Supporters: Two moose.”

The number of trees and whether the tallest one is on the right or left is something that is usually left out of a blazon because it is a detail best left to the judgement of artists. The crown is not just any crown, but the Royal Crown which was inserted into many freely adopted municipal arms in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. The background colour of the 1st and 4th quarters is Gules (red) and that of the 2nd and 3rd quarters is Azure (blue), which is the colour retained today. For more recent renderings and the meaning of the motto, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_John,_New_Brunswick.

In the collection of heraldic china my wife and I collected, two pieces with the arms of St. John are by The Foley China (Wileman & Co.), one by Shelley China (Late Foley), one by Florentine China (Taylor & Kent), and three by Adams. Two of the Adams are blue jasper with the completely white arms in relief. The Foley ones (figs. 11 and 12) and the Shelley one all display the same design. In all of them, the field colour of the 1st quarter is a light green, the 2nd quarter is gold, the 3rd quarter is blue and the 4th quarter is red. Between figure 11 and figure 12, the differently shaped crowns, one with lowered and the other with raised arches, are options that the artists have chosen. For instance, during the reign of Victoria, both types of crowns ensigned the royal arms at one time or another. [9]

Chapin describes the armorial bearings of Saint John thus: “Quarterly (1) gules a barrel between four fish, in chief a fish, all or; (2) azure on a champagne a row of trees graduated in height and in chief a sun in splendour or; (3) azure a ship or at sea barry undy or and azure; (4) gules two beavers in pale or. The number of trees varies from four to seven and sometimes the highest is at dexter and sometimes at sinister. Crest: A crown. Motto; ‘O fortunati quorum jam moenia surgent’. Supporters: Two moose.”

The number of trees and whether the tallest one is on the right or left is something that is usually left out of a blazon because it is a detail best left to the judgement of artists. The crown is not just any crown, but the Royal Crown which was inserted into many freely adopted municipal arms in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. The background colour of the 1st and 4th quarters is Gules (red) and that of the 2nd and 3rd quarters is Azure (blue), which is the colour retained today. For more recent renderings and the meaning of the motto, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_John,_New_Brunswick.

In the collection of heraldic china my wife and I collected, two pieces with the arms of St. John are by The Foley China (Wileman & Co.), one by Shelley China (Late Foley), one by Florentine China (Taylor & Kent), and three by Adams. Two of the Adams are blue jasper with the completely white arms in relief. The Foley ones (figs. 11 and 12) and the Shelley one all display the same design. In all of them, the field colour of the 1st quarter is a light green, the 2nd quarter is gold, the 3rd quarter is blue and the 4th quarter is red. Between figure 11 and figure 12, the differently shaped crowns, one with lowered and the other with raised arches, are options that the artists have chosen. For instance, during the reign of Victoria, both types of crowns ensigned the royal arms at one time or another. [9]

Fig. 11. Dainty white bone china vase by the Foley China (Wileman & Co.) c. 1900. Inscribed in black on bottom, below mark: “MADE IN ENGLAND FOR W.H. HAYWARD.”

Fig. 12. Bone china tumbler by the Foley China (Wileman & Co.). Inscribed in black on opposite side: “WITH THE COMPLIMENTS OF W.H. HAYWARD CO. LTD. ST. JOHN N.B. FANCY CHINA ETC; ON THEIR 50TH ANNIVERSARY 1855-1905.”

Fig. 13. Pottery plate by Adams, c. 1905. The 3rd quarter with the ship is Argent (white) rather than blue as in figures 11 and 12.

In figure 14 the 1st quarter becomes red and the 4th quarter turns to gold along with the beavers, which are visually difficult to discern. The two other quarters are blue. The whole is within a garter inscribed “St. John N.B.” and ensigned by the Royal Crown. It is a poor rendering which, once again, demonstrates that heraldic devices that are not properly recorded are subject to the whims of artists, quite often with deterioration in clarity.

Fig. 14. Arms of St. John on a miniature ivory bone china pin dish by Florentine China (Taylor & Kent), c. 1910.

Quebec

Montreal

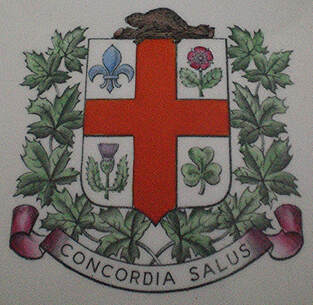

In 1833 Jacques Viger, first mayor of Montreal, created an armorial design for use on the corporate seal of the city. He had several drawings made in oval and round shapes as was required for the seal. Two artists were involved, one of them being James Duncan who is well known for his views of Montreal. The composition of the seal is described in the minutes of a council meeting of 19 July 1833. The description translates as follows: “an oval shape with a field Argent (silver or white) divided quarterly by a saltire Gules (red), in the 1st quarter a rose, 2nd a thistle, 3rd a shamrock, 4th a beaver passant all Or (gold or yellow). Motto: Concordia Salus on a garter Azure (blue). Under the shield, the inscription “Corporation” — “Montreal.” [10]

The emblem attempts to promote harmonious relations among the inhabitants of the city: the rose at the top represents citizens of English descent; the thistle on the left honours Scottish origins; the shamrock on the right symbolizes Irish ancestry and the beaver in base stands for the Canadians of French descent. The motto which translates “Salvation through harmony” conveys the same idea of getting along well together. The red saltire seems a compromise serving the same purpose. The saltire of Scotland being white and the English cross of St. George being red, the red saltire likely constitutes a synthesis of the two crosses.

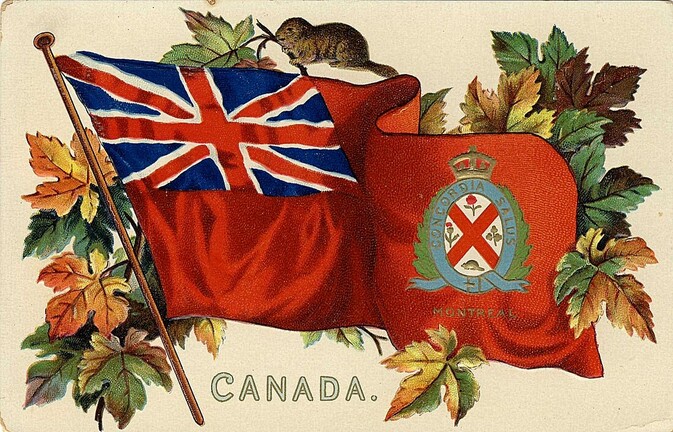

A seal is not coloured. The fact that colours were specified for its components implies that armorial bearings were also intended for the city. The only depiction I have found that comes close to the original description of the seal is in the fly of the Red Ensign (fig. 15). The differences are that the rose and thistle should be solid gold without any red and that the Royal Crown has been placed on top of the garter. A drawing dated 1833 by the artist William Bent Berczy clearly demonstrates that the symbols accompanying the cross were rendered in natural colours by artists from the very beginning and not in gold as specified for the seal. [11] Berczy’s title translates “Arms of the City of Montreal” which signals a mental transition from a seal to an armorial device. In 1880 John Woodward blazons the arms as “Or, a saltire gu., fimbriated arg., between in chief a rose, in flanks a thistle and a shamrock, and in base a beaver, all ppr.” [12] According to this description, the field would be gold (Or), the red saltire would be edged white or silver (Argent) and everything else would be proper, that is in natural colours. It constitutes another early variation on the city’s emblem.

In 1833 Jacques Viger, first mayor of Montreal, created an armorial design for use on the corporate seal of the city. He had several drawings made in oval and round shapes as was required for the seal. Two artists were involved, one of them being James Duncan who is well known for his views of Montreal. The composition of the seal is described in the minutes of a council meeting of 19 July 1833. The description translates as follows: “an oval shape with a field Argent (silver or white) divided quarterly by a saltire Gules (red), in the 1st quarter a rose, 2nd a thistle, 3rd a shamrock, 4th a beaver passant all Or (gold or yellow). Motto: Concordia Salus on a garter Azure (blue). Under the shield, the inscription “Corporation” — “Montreal.” [10]

The emblem attempts to promote harmonious relations among the inhabitants of the city: the rose at the top represents citizens of English descent; the thistle on the left honours Scottish origins; the shamrock on the right symbolizes Irish ancestry and the beaver in base stands for the Canadians of French descent. The motto which translates “Salvation through harmony” conveys the same idea of getting along well together. The red saltire seems a compromise serving the same purpose. The saltire of Scotland being white and the English cross of St. George being red, the red saltire likely constitutes a synthesis of the two crosses.

A seal is not coloured. The fact that colours were specified for its components implies that armorial bearings were also intended for the city. The only depiction I have found that comes close to the original description of the seal is in the fly of the Red Ensign (fig. 15). The differences are that the rose and thistle should be solid gold without any red and that the Royal Crown has been placed on top of the garter. A drawing dated 1833 by the artist William Bent Berczy clearly demonstrates that the symbols accompanying the cross were rendered in natural colours by artists from the very beginning and not in gold as specified for the seal. [11] Berczy’s title translates “Arms of the City of Montreal” which signals a mental transition from a seal to an armorial device. In 1880 John Woodward blazons the arms as “Or, a saltire gu., fimbriated arg., between in chief a rose, in flanks a thistle and a shamrock, and in base a beaver, all ppr.” [12] According to this description, the field would be gold (Or), the red saltire would be edged white or silver (Argent) and everything else would be proper, that is in natural colours. It constitutes another early variation on the city’s emblem.

Fig. 15a-b. Postcard c. 1910 by “Raphael Tuck & Sons ‘Canadian Coats of Arms’ Post Card Series No. 2911. Art publishers to Their Majesties the King and Queen. Printed in Saxony.”

Howard Chapin blazons the shield of Montreal: “Argent a saltire gules between a rose, a thistle, a trefoil, and a beaver passant or. [13] Motto: ‘Concordia salus’.” He remarks: “The trefoil is shown as three trefoils on one stalk but is blazoned officially as ‘a trefoil’. The shield is usually oval and encircled by a blue garter charged with the motto and the two tails of the garter are charged with the words ‘Corporation Montreal’. All the lettering is sable. The trefoil doubtless is considered to be a shamrock.” [14] The trefoil is shaped as in figure 16, but in his own drawing Chapin depicts a shamrock (fig. 17) which no doubt reflects his comment that a shamrock was likely intended. The word “trèfle” in the original description of the seal designates a three-leaf clover in French heraldry.

Fig. 16. A trefoil has three nippled lobes, usually on a curved and pointed stem.

Fig. 17. Colourized version of the arms of Montreal from a line print in Howard M. Chapin, “Canadian Municipal Arms”, 1937, p. 248.

The emblem of Montreal probably appeared for the first time on ceramics in the 1860s, namely on pieces of tableware of the Ocean Steamship Company where it is printed in black and white. [15] It also decorates a number of Wedgwood plates in the royal pattern with red, blue or green borders (fig. 18) and is also seen on tableware decorated with a wreath of oak leaves (fig. 19), both before, during and slightly after the First World War. In figures 18 to 20, the field is now gold, the saltire is white instead of red and all the elements around it are in natural colours. The beaver is placed on a torse as if it were a crest. The Royal Crown above the garter has lowered arches in some cases and in others raised ones.

Fig. 18. Pottery Wedgwood plate, royal pattern with green border, 1917.

Fig. 19. Pottery sugar bowl with lid and oak wreath ornament by Wedgwood, c. 1902.

Carlton China produced a number of miniature souvenirs with the old device of Montreal. On them the field is gold, the saltire becomes blue and the accompaniments are all in natural colours. A mural crown, which is the symbol of a city, is placed above the garter (fig. 20).

Fig. 20. Miniature bone china tree trunk vase by Carlton China (Wiltshaw and Robinson Ltd.). The maker’s mark dates from 1902 to 1930, but the piece is likely prior to the First World War when such souvenirs were most popular.

In figure 21 the saltire cross has returned to white as in figures 18 and 19, but the field is now red and celestial blue. The accompanying charges are all gold as in the original description of the seal and the beaver is on a log. The shield is no longer oval, the garter has gone, the motto is on a scroll below the shield, but there is still the Royal Crown on top of the shield. Over time, the achievement of arms of Montreal underwent huge variations with many types of supporters added and different inscriptions. [16]

Fig. 21. Bone china coffee can by E. Hughes & Co., mark 1905-12.

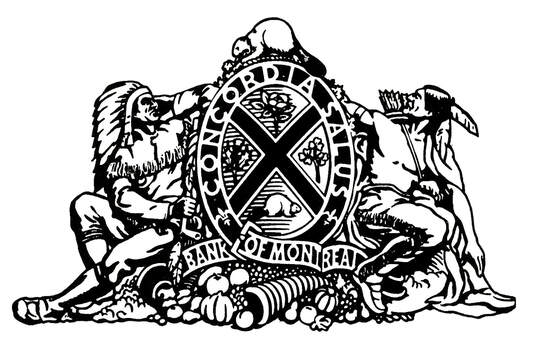

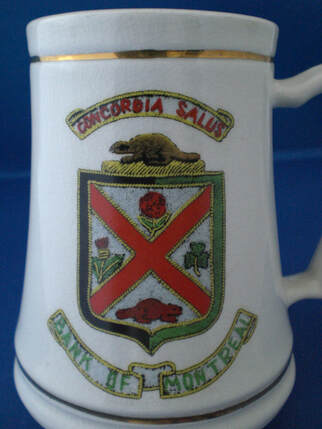

The Bank of Montreal used the arms of Montreal on a half penny bank token of 1837 and on a five dollars bill issued in 1852 to which were added two First Nation supporters and a beaver crest.[17] Figure 22 is another example often seen carved in stone on the pediment of Bank of Montreal buildings. The achievement of arms was granted by the English Kings of arms on 21 April 1934 and registered by the Canadian Heraldic Authority on 16 November 1992: https://www.gg.ca/en/heraldry/public-register/project/1554. Figure 23 shows an example of these arms without supporters.

Fig. 22. From Heraldry in Canada (June 1982), p. 27.

Fig. 23. The depiction is faithful to the 1934 grant of arms to the Bank of Montreal, but without supporters. Pottery stein made in England, 1950s to 1980s?

In 1938 the municipal council adopted a new armorial design for Montreal (fig. 24). The shield is of the type most prevalent in France during the eighteen and nineteenth centuries. The cross is no longer a saltire but a red cross on a white field. Although it is the same as the cross of St. George, patron saint of England, it also has a long historical association with France. [18] In the arms of Montreal, the cross has no ethnic connotation. It honours the Christian tradition that presided over the foundation and development of Ville-Marie which became Montreal. A memorable Christian gesture took place in 1643 when Chomedey de Maisonneuve, founder of Fort Ville-Marie, carried a cross to the top of Mount Royal and had it planted there to thank God for having protected the settlement from the rising waters of the St. Lawrence River. This explains the large illuminated cross that dominates Mount Royal today.

The blue fleur-de-lis, which has become the symbol of French Canadians and of the Province of Quebec occupies the 1st quarter of the shield. The rose of England, the thistle of Scotland and the shamrock of Ireland, all in natural colours, are derived from the older design and represent the origins of the city’s founders. The beaver which was previously in base of the shield is now placed on a log as the crest on top of the shield. The original motto Concordia Salus appears on a scroll below as is most frequent in heraldry. The branches of maple outside the shield are a common feature in Quebec civic heraldry.

The blue fleur-de-lis, which has become the symbol of French Canadians and of the Province of Quebec occupies the 1st quarter of the shield. The rose of England, the thistle of Scotland and the shamrock of Ireland, all in natural colours, are derived from the older design and represent the origins of the city’s founders. The beaver which was previously in base of the shield is now placed on a log as the crest on top of the shield. The original motto Concordia Salus appears on a scroll below as is most frequent in heraldry. The branches of maple outside the shield are a common feature in Quebec civic heraldry.

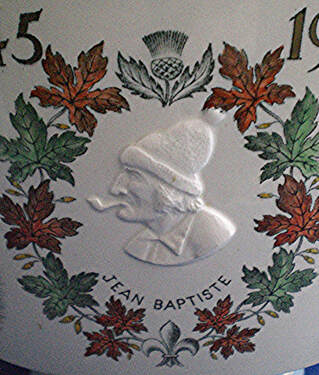

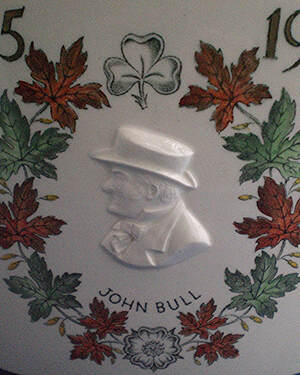

Fig. 24a-c. The 1938 arms of Montreal inside a footed pottery punch bowl by Wedgwood. The bowl features many pictures and inscriptions on the outside regarding historic aspects and the population of the city, including the effigies of Jean-Baptiste and John Bull inside a wreath of maple leaves and floral emblems as also found with the city’s arms. The bowl was given to employees of Morgan’s in 1945 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the founding of the store by Henry Morgan.

The 1938 arms remained in use until 25 September 2017 when a white pine tree was added in the centre of the cross to honour the original indigenous presence on the territory. A torse was also placed under the beaver on a log in the crest. See the complete blazon and symbolism as recorded by the Canadian Heraldic Authority: https://www.gg.ca/en/heraldry/public-register/project/2960.

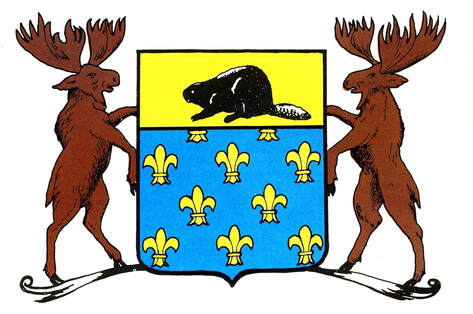

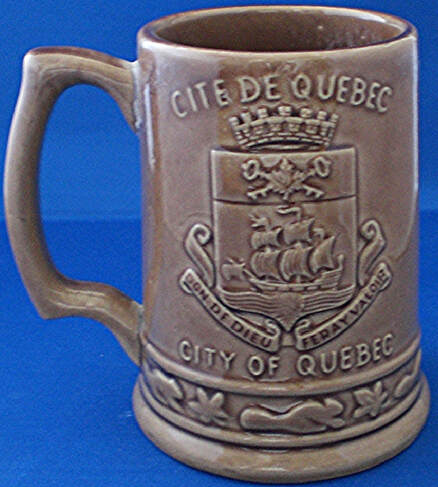

Quebec City

In 1673 Louis Buade de Frontenac, Governor of New France, proposed arms for the City of Quebec to the minister of colonies. They displayed a beaver in the upper part of the shield which is supported by two moose. The governor also recommended blue and white as the city’s livery colours. [19] The shield is blazoned: Azure semy of fleurs-de-lis, on a chief Or a beaver Sable (fig. 25). For some reason, the minister did not endorse this proposition which would have made Quebec the first Canadian city to obtain officially granted arms.

In 1673 Louis Buade de Frontenac, Governor of New France, proposed arms for the City of Quebec to the minister of colonies. They displayed a beaver in the upper part of the shield which is supported by two moose. The governor also recommended blue and white as the city’s livery colours. [19] The shield is blazoned: Azure semy of fleurs-de-lis, on a chief Or a beaver Sable (fig. 25). For some reason, the minister did not endorse this proposition which would have made Quebec the first Canadian city to obtain officially granted arms.

Fig. 25. Achievement of arms proposed for Quebec City by Governor Frontenac in 1673. From Heraldry in Canada (Sept. 1982), p. 35.

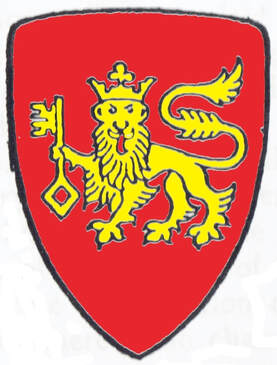

The first arms adopted by Quebec City existed in 1833 since they are held by the goddess Ceres in the first seal of the city designed that year (figs. 28-32). Howard Chapin describes them in 1937: “Gules a lion passant guardant crowned holding in his dexter paw a key palewise wards upwards or. Motto: ‘Natura fortis industria crescit’. ” In some depictions a gold bordure has been added as if it were rivetted on. This is no doubt a latter decorative addition since this bordure is absent from the original city seal (fig. 28) and from most early depictions. The arms of the city with a crowned lion holding a key are carved by Cléophas Soucy outside the Peace Tower in Ottawa: https://theroadhome.ca/2018/09/19/12-things-you-didnt-know-about-the-peace-tower-in-ottawa/#jp-carousel-2261.

Fig. 26. The first arms of Quebec City were in use for over a hundred years. Colourized line print from Chapin’s “Canadian Municipal Arms”, p. 248.

Fig. 27. On this postcard by W.G. MacFarlane of Toronto, the colours on the shield are reversed. Another series of postcards by an unknown publisher show the colours as in figure 26 but with a mural crown above as seen here: https://www.vintagepostcards.ca/collections/Patriotics/PatrioticGreetings/.

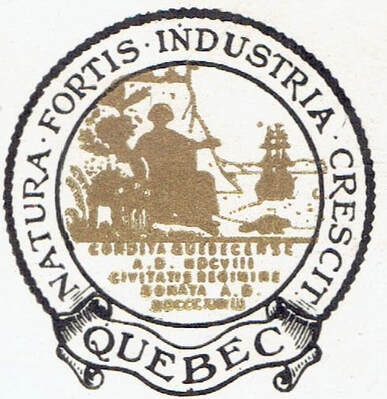

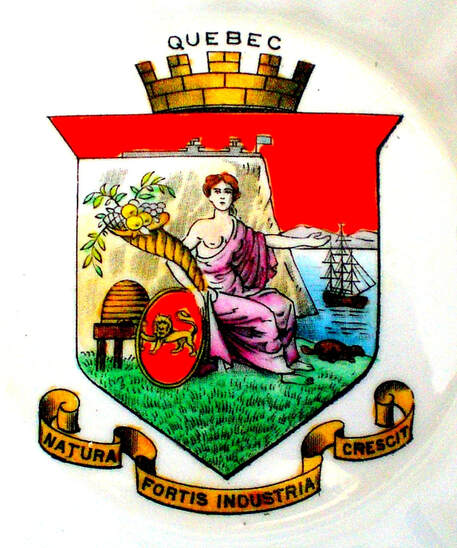

The first seal of Quebec was designed in 1833 by the well-known Canadian artist Joseph Légaré, a counsellor of the city from 1833 to 1836 (fig. 28). Some depictions added to the décor the inscription QUEBEC on a scroll at the base and an inner circle enclosing the pictorial elements (fig. 29). The motto NATURA FORTIS INDUSTRIA CRESCIT (Strong Nature Prospers by Work) appears on the perimeter. The inscription at the base (exergue) CONDITA QUEBECENSE A.D. MDCVIII CIVITATIS REGIMINE DONATA MDCCCXIII means “Quebec was founded in 1608 and incorporated as a city in 1833”. On ceramic souvenirs. the first seal of Quebec was often converted into an armorial device with colours displayed on a shield (figs. 30-31). These images offer a clearer depiction of the pictorial components. The seated figure is Ceres, goddess of agriculture, holding her traditional horn of plenty or cornucopia and accompanied to the right by a beehive. With her right hand, she holds the first armorial shield of the city. With her left hand, she points to the adjacent St. Lawrence River with a ship on it. A beaver walks away from her towards the water. In the background appears a view of the Cap-aux-Diamants crowned by the Citadel fortress.

Fig. 28. The first seal of Quebec City as designed by Joseph Légaré in 1833, impressed directly on the face of an 1855 document into a wafer of wax covered by a square of paper. Library and Archives Canada, MG 24, F 42, negative no. C – 130753.

Fig. 29. The first seal of Quebec City with some additions, on a postcard by Richmond News Co., Richmond, Virginia, c. 1905. Several depictions of the seal can be viewed on this site: https://manegemilitaire.ca/en/coat-of-arms-and-emblems-of-quebec-city/.

Fig. 30a-b. Miniature vase with diamond shaped mouth by W.H. Goss, ivory porcelain, c. 1910. Based on the first seal of Quebec City (fig. 28). The first arms of Quebec are held by the goddess Ceres.

Fig. 31. Old arms of Quebec City derived from its first municipal seal. On a bowl by The Foley China (Wileman & Co.), dated 1900-10.

Fig. 32. The city seal, without the inscription in base, is placed on a cartouche and ensigned by the Royal Crown, the whole within maple branches. Royal pattern Wedgwood plate with red border, 1910.

The arms of the City of Quebec (fig. 33), were chosen by a committee for which the well-known art historian, Gérard Morisset, and the sculptor and stained glass artist, Marius Plamondon, acted as consultants. The committee’s report is dated 17 May 1949 and the arms were adopted by the City Council that same day. The version granted to the city on 20 September 1988 was the first municipal grant by the Chief Herald of Canada. The only addition to the composition is a small gold border at the lower edge of the chief to give it greater relief by separating two colours with a metal. The symbolism of the granted arms remains basically the same as the 1949 version, see: https://www.gg.ca/en/heraldry/public-register/project/1826. The motto “Don de Dieu feray valoir” (I will make good of God's gift) refers to the Don de Dieu, one of the important ships of Samuel de Champlain who established the first permanent French settlement at Quebec. [20] This new motto expresses in another way the old motto on the seal (figs. 28-32) which translates “Strong Nature Prospers by Work”.

Fig. 33. Colourized version of the arms of Québec City 1949-88, from a line print.

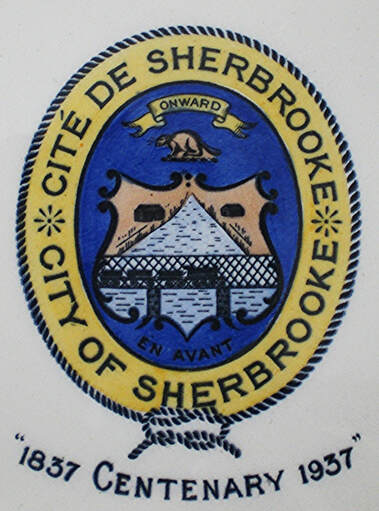

Sherbrooke

Chapin describes the arms of Sherbrooke as follows; “Argent a river palewise between two houses and at base crossed by a railroad bridge with lattice work sides on two piers with a railroad train engine and three cars on the bridge (all azure). Crest: A beaver. Motto: ‘Onward’.” Figure 34 does not correspond to Chapin’s blazon as to the positioning of the river. It is one of the few instances of Canadian municipal arms on British ceramic after the First World War. The Institut généalogique Drouin designed new arms for the city which are a great improvement on the previous design: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Armoiries_de_Sherbrooke.

Chapin describes the arms of Sherbrooke as follows; “Argent a river palewise between two houses and at base crossed by a railroad bridge with lattice work sides on two piers with a railroad train engine and three cars on the bridge (all azure). Crest: A beaver. Motto: ‘Onward’.” Figure 34 does not correspond to Chapin’s blazon as to the positioning of the river. It is one of the few instances of Canadian municipal arms on British ceramic after the First World War. The Institut généalogique Drouin designed new arms for the city which are a great improvement on the previous design: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Armoiries_de_Sherbrooke.

Fig. 34. Old arms of Sherbrooke on a pottery plate made by Spode & Copeland for the centenary of the city.

Ontario

Hamilton

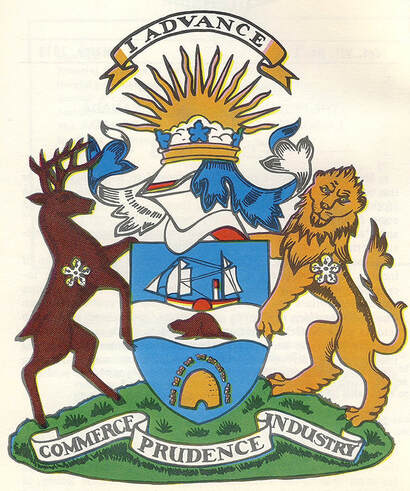

Chapin’s description of the arms of Hamilton reads: “Vert a beehive beset with a demi-orle of eleven bees volant (or), on a chief undy argent at dexter a single-masted lake steamer with funnel at stern and at sinister a beaver. Crest: A demi-sun in splendour issuant from clouds with above the sun the motto ‘I advance’. Motto: ‘Commerce, prudence, industry’. Supporters: Dexter a stag, sinister a lion.” His blazoning does not specify any tinctures for the steamer, the beaver, the entire crest and the supporters. In figure 35, all these elements are more or less proper, that is in natural colours. In figure 36, the same elements become gold. In figure 35, the chief is Argent (silver or white), while in figure 36, it is Gules (red).

Chapin’s description of the arms of Hamilton reads: “Vert a beehive beset with a demi-orle of eleven bees volant (or), on a chief undy argent at dexter a single-masted lake steamer with funnel at stern and at sinister a beaver. Crest: A demi-sun in splendour issuant from clouds with above the sun the motto ‘I advance’. Motto: ‘Commerce, prudence, industry’. Supporters: Dexter a stag, sinister a lion.” His blazoning does not specify any tinctures for the steamer, the beaver, the entire crest and the supporters. In figure 35, all these elements are more or less proper, that is in natural colours. In figure 36, the same elements become gold. In figure 35, the chief is Argent (silver or white), while in figure 36, it is Gules (red).

Fig. 35. Royal pattern Wedgwood plate with red border, 1914.

Fig. 36. Postcard titled “Post Office, Hamilton, Ont.”, c. 1905 by W.G. MacFarlane, Publisher, Toronto.

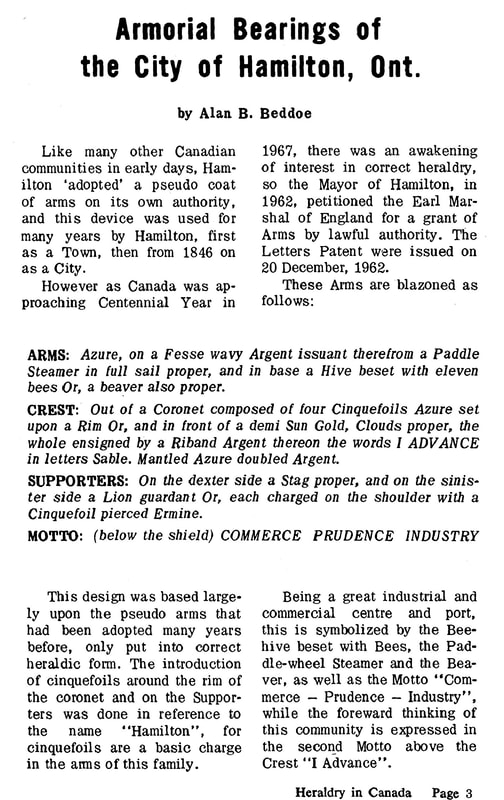

Figure 37 shows and figure 38 describes the armorial bearings granted to the city of Hamilton by the Kings of Arms of England on 20 December 1962. The new design repositions the components of the older one. The city was granted new arms by The Chief Herald of Canada on 15 July 2003 following its amalgamation with several other municipalities: https://www.gg.ca/en/heraldry/public-register/project/99. Of the former arms, only the stag supporter was kept; a tiger replaces the lion supporter and the motto is entirely new.

Fig. 37. Armorial bearings granted to the City of Hamilton by the Kings of Arms of England in 1962, drawn by Alan B. Beddoe, from Heraldry in Canada, March 1973, p. 2.

Fig. 38. Blazon and symbolism of the armorial bearings of the City of Hamilton from Heraldry in Canada, March 1973.

Kenora

According to Chapin, Kenora’s device is composed “Quarterly (1) a flour sack; (2) a pickaxe and shovel in saltire handles downwards; (3) a British soldier in uniform of about 1870, climbing a mountain side with a staff in his hand; (4) a waterfall. Crest: A beaver.”

The origins of the design are not known. There does not seem to be any explanation of the symbolism although much of it can be deduced plausibly. The flour sac refers to the flour milling industry, namely the Maple Leaf Flour Mills. The pickaxe and shovel represent the mining industry, the city being located in the heart of the mineral rich Canadian Shield. The British soldier must allude in some way to the British troops commanded by Colonel Garnet Wolseley who came through Rat Portage (former name of Kenora) in 1870 on their way to the Red River. The waterfall relates to several examples of this phenomenon in the area. The beaver symbolizes the fur trade and the Hudson’s Bay Company that established a post there in 1837 (fig. 39).

According to Chapin, Kenora’s device is composed “Quarterly (1) a flour sack; (2) a pickaxe and shovel in saltire handles downwards; (3) a British soldier in uniform of about 1870, climbing a mountain side with a staff in his hand; (4) a waterfall. Crest: A beaver.”

The origins of the design are not known. There does not seem to be any explanation of the symbolism although much of it can be deduced plausibly. The flour sac refers to the flour milling industry, namely the Maple Leaf Flour Mills. The pickaxe and shovel represent the mining industry, the city being located in the heart of the mineral rich Canadian Shield. The British soldier must allude in some way to the British troops commanded by Colonel Garnet Wolseley who came through Rat Portage (former name of Kenora) in 1870 on their way to the Red River. The waterfall relates to several examples of this phenomenon in the area. The beaver symbolizes the fur trade and the Hudson’s Bay Company that established a post there in 1837 (fig. 39).

Fig. 39. Arms of Kenora on pottery coffee mug by John Tams 1990s?

Kingston

An early version of an armorial device for Kingston appears on the front page of the Canadian Illustrated News of 14 June 1879 showing the vice-regal reception of the Marquis of Lorne and Princess Louise in front of Kingston City Hall. The couple arrived there on May 29 and left on June 3. The shield is placed at the bottom of the page on a scroll inscribed “Welcome to Kingston”. It is divided horizontally into two halves. At the very top is the motto PRO REGE GREGE LEGE, which means “For the king, the people and the law” and which the city kept for at least 120 years. Underneath appears the bust of a crowned king holding a sceptre in his right hand and an orb in the left. The lower half contains a view of Kingston Harbour, not unlike the one in figures 40ab. A border encloses the whole and is red as indicated by vertical lines. The message is very clear: “the king’s town.” The shield can be viewed online: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_06230_500/2.

In 1937 Chapin blazons the arms of Kingston thus: “Argent a chevron gules between in chief two crowns the dexter one English and the sinister one French, and in base (a view of the entrance to the harbour) at dexter a government building with a dome and two wings with lesser domes, at sinister a fort issuing from the edge of the shield with a flag and flag pole at the dexter end of the fort, in base a man in a canoe. Crest: A beaver. Motto: ‘Pro rege lege grege’. Supporters: A lion and a unicorn both rampant.” Though some colours are lacking, this description generally corresponds to figures 40a-b. The motto given by Chapin translates “For the king, the law and the people” instead of “For the king, the people and the law”, which is the order of words for Kingston’s motto. This is likely a mistake in reading. On a scroll, a motto is often divided into three parts, and it is often difficult to see the sequence of words at first glance (see fig. 40b).

Fort Frontenac (also called Cataracoui or Cataraqui) was built in 1673 as an advanced trading post at Kingston by the French Governor Louis de Buade, Comte de Frontenac. It was captured in1758 by English troops commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John Bradstreet. The beaver in the crest highlights the importance of the early fur trade for which the fort was built. The two crowns refer to both the French and English period. The government building is the impressive Kingston City Hall dating from 1844 which faces Lake Ontario and was declared a national historic site in 1961. The fort is very likely Fort Henry which was built during the war of 1812. The water and canoe represent Kingston Harbour. The lion and unicorn supporters come from the royal arms of the United Kingdom. Their bluish tint in figure 40a-b no doubt reflects the fancy of an artist.

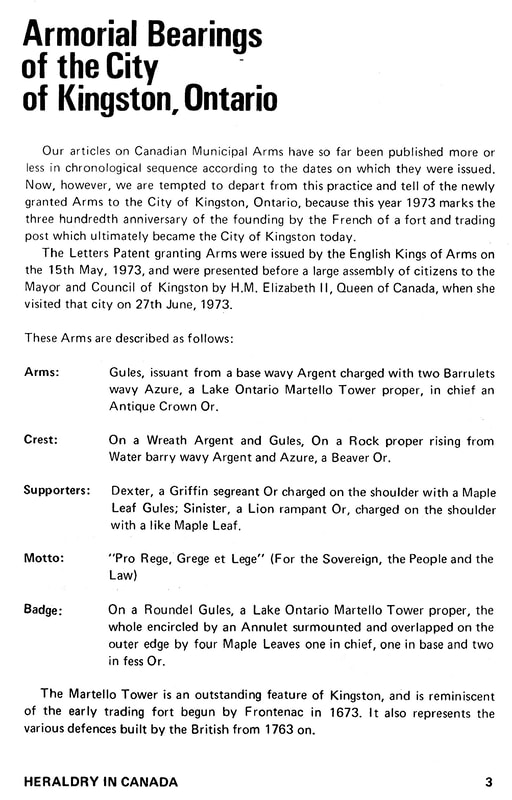

The City of Kingston was granted armorial bearings by the English Kings of Arms on 15 May 1973 (figs. 41-42). A modified version of these arms was granted by the Chief Herald of Canada on 11 January 1999, following a 1998 amalgamation: https://www.gg.ca/en/heraldry/public-register/project/871. For the symbolism of the components, see: https://www.cityofkingston.ca/cok/bylaws/2007/doc/doc926613.PDF.

Kingston presents a good example of a logical progression in the symbols that its citizen chose to represent their city. The first choices were assumed arms that contained flaws, namely a lower portion taking the form of a tableau of outstanding municipal features and far too busy to be easily recognized in smaller size as exemplified by figure 40a-b; supporters that were lifted from the royal arms and surely without royal permission. The city then obtained granted arms with a much improved design and did not hesitate to secure a second grant when a new situation arose.

An early version of an armorial device for Kingston appears on the front page of the Canadian Illustrated News of 14 June 1879 showing the vice-regal reception of the Marquis of Lorne and Princess Louise in front of Kingston City Hall. The couple arrived there on May 29 and left on June 3. The shield is placed at the bottom of the page on a scroll inscribed “Welcome to Kingston”. It is divided horizontally into two halves. At the very top is the motto PRO REGE GREGE LEGE, which means “For the king, the people and the law” and which the city kept for at least 120 years. Underneath appears the bust of a crowned king holding a sceptre in his right hand and an orb in the left. The lower half contains a view of Kingston Harbour, not unlike the one in figures 40ab. A border encloses the whole and is red as indicated by vertical lines. The message is very clear: “the king’s town.” The shield can be viewed online: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_06230_500/2.

In 1937 Chapin blazons the arms of Kingston thus: “Argent a chevron gules between in chief two crowns the dexter one English and the sinister one French, and in base (a view of the entrance to the harbour) at dexter a government building with a dome and two wings with lesser domes, at sinister a fort issuing from the edge of the shield with a flag and flag pole at the dexter end of the fort, in base a man in a canoe. Crest: A beaver. Motto: ‘Pro rege lege grege’. Supporters: A lion and a unicorn both rampant.” Though some colours are lacking, this description generally corresponds to figures 40a-b. The motto given by Chapin translates “For the king, the law and the people” instead of “For the king, the people and the law”, which is the order of words for Kingston’s motto. This is likely a mistake in reading. On a scroll, a motto is often divided into three parts, and it is often difficult to see the sequence of words at first glance (see fig. 40b).

Fort Frontenac (also called Cataracoui or Cataraqui) was built in 1673 as an advanced trading post at Kingston by the French Governor Louis de Buade, Comte de Frontenac. It was captured in1758 by English troops commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John Bradstreet. The beaver in the crest highlights the importance of the early fur trade for which the fort was built. The two crowns refer to both the French and English period. The government building is the impressive Kingston City Hall dating from 1844 which faces Lake Ontario and was declared a national historic site in 1961. The fort is very likely Fort Henry which was built during the war of 1812. The water and canoe represent Kingston Harbour. The lion and unicorn supporters come from the royal arms of the United Kingdom. Their bluish tint in figure 40a-b no doubt reflects the fancy of an artist.

The City of Kingston was granted armorial bearings by the English Kings of Arms on 15 May 1973 (figs. 41-42). A modified version of these arms was granted by the Chief Herald of Canada on 11 January 1999, following a 1998 amalgamation: https://www.gg.ca/en/heraldry/public-register/project/871. For the symbolism of the components, see: https://www.cityofkingston.ca/cok/bylaws/2007/doc/doc926613.PDF.

Kingston presents a good example of a logical progression in the symbols that its citizen chose to represent their city. The first choices were assumed arms that contained flaws, namely a lower portion taking the form of a tableau of outstanding municipal features and far too busy to be easily recognized in smaller size as exemplified by figure 40a-b; supporters that were lifted from the royal arms and surely without royal permission. The city then obtained granted arms with a much improved design and did not hesitate to secure a second grant when a new situation arose.

Fig. 40a-b. Ivory bone china toby souvenir jug commemorating the 250th anniversary of Kingston, 1673-1923, by Robertsons Art China. Pin dish by same company.

Fig. 41. Armorial bearings of Kingston granted by the English Kings of Arms on 15 May 1973. Here “ET” has been added to the motto which clarifies the sequence of words on the scroll, but the meaning remains the same. From Heraldry in Canada (December 1973), p. 2.

Fig. 42. From Heraldry in Canada (December 1973), p. 3.

Nepean

Nepean was named in honour of Sir Evan Nepean, head of the colonial branch of the British Home Office and secretary to the Board of Admiralty. The municipal arms were approved by the City of Nepean on 10 November 1981. They are partly based on the personal arms of city’s namesake. The field of the shield is changed from red to green. The white stars are replaced by “three representations of the old township hall bell as hanging from its support in the Nepean Civic Square” also white. The goat in the crest acquired a collar of gold maple leaves. The city chose its own appropriate motto as seen in figure 43. The arms were granted by the Chief Herald of Canada on 10 October 1990: https://www.gg.ca/en/heraldry/public-register/project/1433. The version on the mug duplicates the one drawn in a somewhat different style on the grant of a flag to the city: https://www.gg.ca/en/heraldry/public-register/project/1488. For comparison with the city, those of Sir Evan Nepean can be viewed here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evan_Nepean.

Nepean was named in honour of Sir Evan Nepean, head of the colonial branch of the British Home Office and secretary to the Board of Admiralty. The municipal arms were approved by the City of Nepean on 10 November 1981. They are partly based on the personal arms of city’s namesake. The field of the shield is changed from red to green. The white stars are replaced by “three representations of the old township hall bell as hanging from its support in the Nepean Civic Square” also white. The goat in the crest acquired a collar of gold maple leaves. The city chose its own appropriate motto as seen in figure 43. The arms were granted by the Chief Herald of Canada on 10 October 1990: https://www.gg.ca/en/heraldry/public-register/project/1433. The version on the mug duplicates the one drawn in a somewhat different style on the grant of a flag to the city: https://www.gg.ca/en/heraldry/public-register/project/1488. For comparison with the city, those of Sir Evan Nepean can be viewed here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evan_Nepean.

Fig. 43. Pottery coffee mug inscribed on bottom “Made in England”.

Orillia

The arms used by the city of Orillia were designed by William Sword Frost, a prominent jeweller and mayor of the city. [21] Chapin describes them: “Per fess, the chief or a sprig of three maple leaves vert, the base argent an Indian paddling a canoe at sea proper. Crest: a crown. Motto: Progress Orillia. Supporters: two deer.” The depiction on the plate (fig. 44) does not correspond to Chapin in that the tinctures in the upper portion are reversed, the field being Vert (green) and the leaves Or (gold). Why should the canoe be paddled at sea, since Orillia is on the shores of two lakes and nowhere near the sea? The arms granted to the city by the Chief Herald of Canada on 27 September 1999 are largely based on the original design: https://www.gg.ca/en/heraldry/public-register/project/868.

The arms used by the city of Orillia were designed by William Sword Frost, a prominent jeweller and mayor of the city. [21] Chapin describes them: “Per fess, the chief or a sprig of three maple leaves vert, the base argent an Indian paddling a canoe at sea proper. Crest: a crown. Motto: Progress Orillia. Supporters: two deer.” The depiction on the plate (fig. 44) does not correspond to Chapin in that the tinctures in the upper portion are reversed, the field being Vert (green) and the leaves Or (gold). Why should the canoe be paddled at sea, since Orillia is on the shores of two lakes and nowhere near the sea? The arms granted to the city by the Chief Herald of Canada on 27 September 1999 are largely based on the original design: https://www.gg.ca/en/heraldry/public-register/project/868.

Fig. 44. Pottery plate by Adams, c. 1905.

Ottawa

George Hay, a Scottish immigrant, businessman, politician, and philanthropist who moved to Bytown claims “to have designed the city’s coat of arms and to have suggested the name Ottawa to replace Bytown”. [22] Chapin describes the old arms of Ottawa as follows: “Quarterly (1) a locomotive and tender; (2) a lake, with in the foreground a tree between two stags the dexter one lodged [lying down], and in the background a range of hills and the sun issuant; (3) the locks of the Rideau canal; (4) Chaudière Falls and the suspension bridge with a boat in the foreground. Crest: ‘A hand holding a cleaving knife’. Motto: ‘Advance’. Supporters: Dexter a workman with hammer in right hand standing behind an anvil and sinister Justice.”

Chapin’s blazon does not contain a single tincture. In the crest, the hand does not hold a “cleaving knife”, but a hewing axe to square timber. [23] Also the “workman” is evidently a blacksmith. A sheaf of grain, a hand holding a hewing axe, a beehive with bees, and a plough adorns the top of Ottawa’s shield as crests. A large cogwheel at the foot of the blacksmith is a symbol of industry. The scroll below the shield is accompanied by roses, thistles and shamrocks (fig. 45). Figure 46 seems an effort to present a simpler design. The unofficial municipal heraldry of the nineteenth century and first half of the twentieth contained many references to agriculture, means of transportation, landscapes and industries which could include an entire factory with smoke stacks. Three of the quarters of Ottawa’s shield are landscapes or cityscapes. The composition reminds us of Jim Reeves song “Railroad, steamboat, river and canal”.

The new arms of Ottawa (fig. 47) were granted by the English Kings of Arms on 15 September 1954 and registered by the Canadian Heraldic Authority, with blazon and symbolism, on 15 June 2001: https://www.gg.ca/en/heraldry/public-register/project/213.

George Hay, a Scottish immigrant, businessman, politician, and philanthropist who moved to Bytown claims “to have designed the city’s coat of arms and to have suggested the name Ottawa to replace Bytown”. [22] Chapin describes the old arms of Ottawa as follows: “Quarterly (1) a locomotive and tender; (2) a lake, with in the foreground a tree between two stags the dexter one lodged [lying down], and in the background a range of hills and the sun issuant; (3) the locks of the Rideau canal; (4) Chaudière Falls and the suspension bridge with a boat in the foreground. Crest: ‘A hand holding a cleaving knife’. Motto: ‘Advance’. Supporters: Dexter a workman with hammer in right hand standing behind an anvil and sinister Justice.”

Chapin’s blazon does not contain a single tincture. In the crest, the hand does not hold a “cleaving knife”, but a hewing axe to square timber. [23] Also the “workman” is evidently a blacksmith. A sheaf of grain, a hand holding a hewing axe, a beehive with bees, and a plough adorns the top of Ottawa’s shield as crests. A large cogwheel at the foot of the blacksmith is a symbol of industry. The scroll below the shield is accompanied by roses, thistles and shamrocks (fig. 45). Figure 46 seems an effort to present a simpler design. The unofficial municipal heraldry of the nineteenth century and first half of the twentieth contained many references to agriculture, means of transportation, landscapes and industries which could include an entire factory with smoke stacks. Three of the quarters of Ottawa’s shield are landscapes or cityscapes. The composition reminds us of Jim Reeves song “Railroad, steamboat, river and canal”.

The new arms of Ottawa (fig. 47) were granted by the English Kings of Arms on 15 September 1954 and registered by the Canadian Heraldic Authority, with blazon and symbolism, on 15 June 2001: https://www.gg.ca/en/heraldry/public-register/project/213.

Fig. 45. Old arms of Ottawa on a bone china bagware bowl by Willow Art China, Stoke-on-Trent. The maker’s mark dates 1925-30. Willow is one of the few British companies to feature Canadian municipal arms on ceramic souvenirs after the First World War.

Fig. 46. Shield of the old armorial bearings of Ottawa on Wedgwood royal pattern pottery plate, blue border, 1912.

Fig. 47. The Arms of Ottawa were granted by the English Kings of Arms on 15 September 1954. From Heraldry in Canada (June, 1969), p. 8.

Parry Sound

Chapin’s blazon of the arms of Parry Sound reads: “Quarterly (1) a lymphad; (2) a fish fesswise; (3) a fir tree; (4) a maple leaf. Crest: a stag passant.” In this description, not a single tincture is mentioned. Obviously, Chapin did not see the plate illustrated below (fig. 48). The design seems to have remained the same over the years. They are the same in Campbell’s 1990 work. [24]

Chapin’s blazon of the arms of Parry Sound reads: “Quarterly (1) a lymphad; (2) a fish fesswise; (3) a fir tree; (4) a maple leaf. Crest: a stag passant.” In this description, not a single tincture is mentioned. Obviously, Chapin did not see the plate illustrated below (fig. 48). The design seems to have remained the same over the years. They are the same in Campbell’s 1990 work. [24]

Fig. 48. Arms of Parry Sound, Ontario, on pottery plate by Adams, c. 1905.

Perth

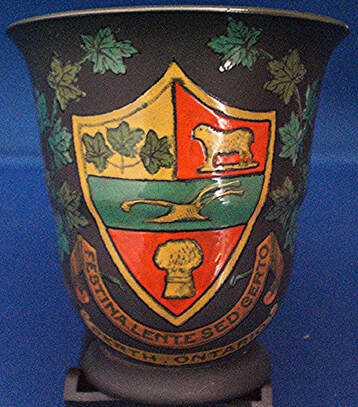

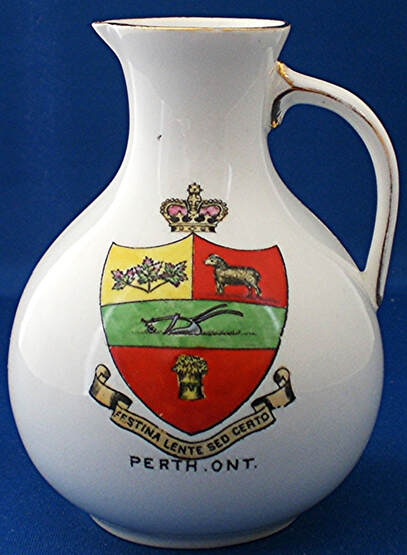

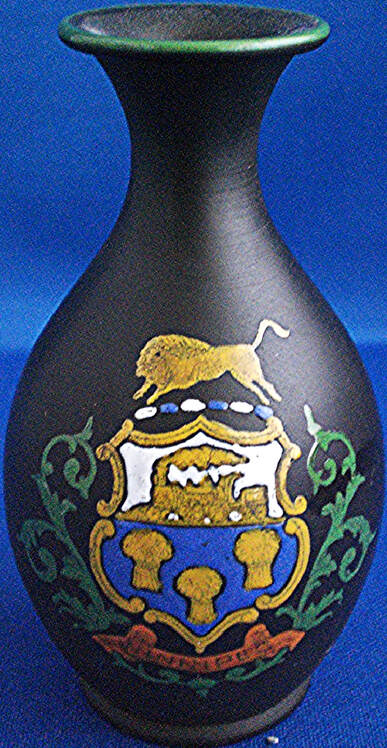

In Chapin’s civic armorial of 1937, the blazon of Perth’s arms reads: “On a fess vert a plow (or), between a chief per pale dexter or a sprig of three maple leaves vert and sinister gules a lamb (sable) and in base gules a garb (or). Motto: ‘Festina lente sed certo’.” The Latin motto signifies “Make haste slowly but surely”. A lamb Sable as in Chapin’s blazon is not likely correct. One of the basic rules of heraldry prohibits a colour being place on a colour or a metal on a metal. Moreover, a black sheep has a pejorative connotation and is not likely to appear in municipal arms unless it has some important historical significance. In figure 49 the gold lamb is on red, a metal on a colour as it should be. In figure 50, the lamb has a golden tint but is so heavily highlighted with black lines that it could be taken to be black. The maple leaves are multicoloured and the plough is silver or white. In an undated embroidery, both the lamb and plough are white: https://www.heraldry-wiki.com/heraldrywiki/wiki/Perth_(Ontario).

Perth was afterwards granted arms by Lord Lyon King of arms which are blazoned: “Gules, a Holy lamb passant reguardant, staff and cross Argent, with the banner of St. Andrew proper, all within an orle of the Second. Below the Shield which is ensigned with a mural coronet Azure, masoned Argent is set this Motto: ‘Pro Rege, Lege, et Grege’.” [25] These arms are largely patterned after those of Perth Scotland, including the motto which, incidentally, is close to that in the former arms of Kingston, except that here “Lege” precedes “Grege” see figures 40-42.

In Chapin’s civic armorial of 1937, the blazon of Perth’s arms reads: “On a fess vert a plow (or), between a chief per pale dexter or a sprig of three maple leaves vert and sinister gules a lamb (sable) and in base gules a garb (or). Motto: ‘Festina lente sed certo’.” The Latin motto signifies “Make haste slowly but surely”. A lamb Sable as in Chapin’s blazon is not likely correct. One of the basic rules of heraldry prohibits a colour being place on a colour or a metal on a metal. Moreover, a black sheep has a pejorative connotation and is not likely to appear in municipal arms unless it has some important historical significance. In figure 49 the gold lamb is on red, a metal on a colour as it should be. In figure 50, the lamb has a golden tint but is so heavily highlighted with black lines that it could be taken to be black. The maple leaves are multicoloured and the plough is silver or white. In an undated embroidery, both the lamb and plough are white: https://www.heraldry-wiki.com/heraldrywiki/wiki/Perth_(Ontario).

Perth was afterwards granted arms by Lord Lyon King of arms which are blazoned: “Gules, a Holy lamb passant reguardant, staff and cross Argent, with the banner of St. Andrew proper, all within an orle of the Second. Below the Shield which is ensigned with a mural coronet Azure, masoned Argent is set this Motto: ‘Pro Rege, Lege, et Grege’.” [25] These arms are largely patterned after those of Perth Scotland, including the motto which, incidentally, is close to that in the former arms of Kingston, except that here “Lege” precedes “Grege” see figures 40-42.

Fig. 49. Old shield of Perth on a Black ironstone (basalt) demitasse by Wedgwood, c. 1900.

Fig. 50. Old shield of Perth on bone china miniature jug by the Foley China (Wileman & Co.), 1900-10.

Toronto

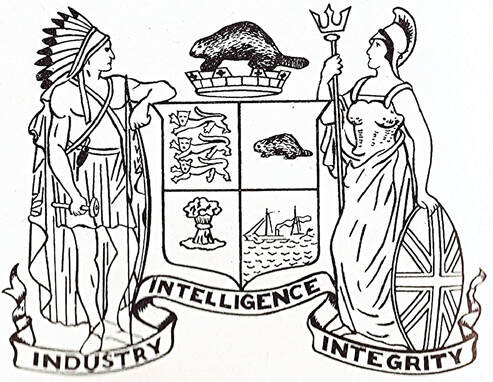

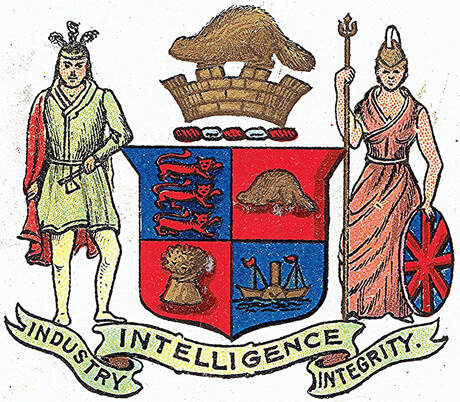

Chapin’s blazon for Toronto reads: “Quarterly (1) gules three lions passant guardant or; (2) or a beaver proper; (3) argent a garb or; (4) azure a steamboat or. Crest: Above a mural crown or, a beaver proper. Motto: ‘Industry, intelligence, integrity’. Supporters: Dexter an Indian habited proper, with in his belt a scalping knife and in his right hand a tomahawk with his left arm leaning on a bow, Sinister Britannia helmed and cuirassed, holding a trident in her right hand and with her left hand resting on a shield charged with the union of the three crosses proper.” Figure 51 corresponds to this description including the scalping knife in the belt seen above the tomahawk in the enlarged detail. The design dates from 1834. [26] In 1880 Woodward describes some of the quarters differently: the second quarter becomes “Sa., a beaver or” which corresponds to a gold beaver on a black field and the third quarter “Sa., a garb or” which means a gold wheat sheaf on a black field. [27] The shield of the first arms of Toronto is among those carved in stone by Cléophas Soucy outside the Peace Tower of the Parliament Building in Ottawa. Soucy also carved these arms in Confederation Hall with the beaver on a mural crown as the crest and the motto on a scroll below the shield.

At least six different manufacturers have featured the arms of Toronto on their ceramic pieces including two examples by W.H. Goss, the famous maker of miniature armorial souvenirs. I have not yet been able to find the arms of Toronto on any Wedgwood item, not on their famous tea sets, nor on their large plates dedicated to many cities across Canada.

Depictions of the first armorial bearings of Toronto have been generally consistent except for the accoutrements of the indigenous supporter. In figure 52, he holds a bow in his left hand, but holds a peace pipe with a long stem in his right hand, not a tomahawk. There exists such a combination as a peace pipe combined with a tomahawk, but their handle is not so long.

Chapin’s blazon for Toronto reads: “Quarterly (1) gules three lions passant guardant or; (2) or a beaver proper; (3) argent a garb or; (4) azure a steamboat or. Crest: Above a mural crown or, a beaver proper. Motto: ‘Industry, intelligence, integrity’. Supporters: Dexter an Indian habited proper, with in his belt a scalping knife and in his right hand a tomahawk with his left arm leaning on a bow, Sinister Britannia helmed and cuirassed, holding a trident in her right hand and with her left hand resting on a shield charged with the union of the three crosses proper.” Figure 51 corresponds to this description including the scalping knife in the belt seen above the tomahawk in the enlarged detail. The design dates from 1834. [26] In 1880 Woodward describes some of the quarters differently: the second quarter becomes “Sa., a beaver or” which corresponds to a gold beaver on a black field and the third quarter “Sa., a garb or” which means a gold wheat sheaf on a black field. [27] The shield of the first arms of Toronto is among those carved in stone by Cléophas Soucy outside the Peace Tower of the Parliament Building in Ottawa. Soucy also carved these arms in Confederation Hall with the beaver on a mural crown as the crest and the motto on a scroll below the shield.

At least six different manufacturers have featured the arms of Toronto on their ceramic pieces including two examples by W.H. Goss, the famous maker of miniature armorial souvenirs. I have not yet been able to find the arms of Toronto on any Wedgwood item, not on their famous tea sets, nor on their large plates dedicated to many cities across Canada.

Depictions of the first armorial bearings of Toronto have been generally consistent except for the accoutrements of the indigenous supporter. In figure 52, he holds a bow in his left hand, but holds a peace pipe with a long stem in his right hand, not a tomahawk. There exists such a combination as a peace pipe combined with a tomahawk, but their handle is not so long.

Fig. 51a-b. In the enlarged detail, the scalping knife is seen on the belt. Encyclopedia Canadiana, vol. 10 (Ottawa: Grolier Society of Canada, 1958), p. 102.

Fig. 52. Dainty white berry bowl by the Foley China (Wileman & Co.), c. 1900. The company also created a lager fruit bowl of the same type and with the same achievement of arms as also found on other pieces of its tableware.

In the collection my wife and I assembled, there are two identical armorial bearings of Toronto by W.H. Goss (figs. 53-54). The indigenous supporter is fully dressed in buckskin with feather headdress, holds the bow in his left hand, and has a quiver of arrows strung across his back (fig. 53b).

Fig. 53a-c. Ivory porcelain model of a drinking cup by W.H. Goss, c. 1905-14. The inscription with the mark should read “Irish mether or wooden drinking cup”. A mether is a ceremonial drinking vessel.

Fig. 54a-b. Ivory porcelain model of an urn by W.H. Goss, c. 1905-14. The orange figure is a decorator’s mark.

The manufacturer’s mark in figure 54 is accompanied by the inscription “MADE IN ENGLAND” (above, to the left). This does not mean that the Irish mether (fig. 53) and the urn (fig. 54) were manufactured at significantly different times [28].

In figure 55, the supporter on the left has a bow strung across his back, a long stick in his right hand, a short skirt or shorts with a piece of cloth covering his backside. The Union Flag pattern on Britannia’s shield is often blundered, but we see here an extreme case: see the correct disposition of the crosses and colouring on figure 58.

In figure 55, the supporter on the left has a bow strung across his back, a long stick in his right hand, a short skirt or shorts with a piece of cloth covering his backside. The Union Flag pattern on Britannia’s shield is often blundered, but we see here an extreme case: see the correct disposition of the crosses and colouring on figure 58.

Fig. 55. Toronto arms displayed on both a bone china cup and saucer by R.H. & S.L. Plant (Tuscan China), c. 1910. Inscribed under both: MADE EXPRESSLY FOR W.A. MURRAY & CO. LTD TORONTO CANADA.

In figure 56, the indigenous supporter leans on his bow and holds a tomahawk in his right hand as noted by Chapin. He wears a short skirt of feathers or strips of fur. This type of skirt was almost the norm on depictions of Amerindians, in and outside heraldry, from the sixteenth to the eighteen centuries. [29] It is still seen in the achievement of arms of Nova Scotia, which dates from 1625 or a little earlier, and it is described in the registration of the Canadian Heraldic Authority as: a “17th-century representation of an Aboriginal holding in the sinister hand an arrow proper”. The heraldic descriptions of humans are usually very short, often simply mentioning a person of a certain type and of a certain period without offering any details as to their wear. Placing this type of skirt on an 1834 supporter can be viewed as an anachronism, but not a severe one since there were two Amerindians dressed this way on the frontispiece of The Quebec Almanack of 1796, only 38 years earlier. [30] Figure 57 depicts the indigenous supporter in still another way.

Fig. 56. Ivory bone china miniature urn by Willow Art China, Longton. The mark dates from 1907-25, but it is likely prior to the First World War as are almost all Canadian miniature examples of this type.

Fig. 57. Heraldic Series B.A.C.T. postcard by Stoddart & Co., Halifax, West Yorkshire, England. A card in this series is postmarked 1906.

In the arms granted Toronto by the English King of Arms on 29 December 1961, a white cross, which divides clearly the shield into four quarters, is added to the design (fig. 58). The red maple leaf in its centre represents Canada. The white rose of York replaces the beaver in the 2nd quarter referring to York, the former name of the city. A cogwheel supplants the wheat sheaf in the 3rd quarter to illustrate that the economy of the city has shifted from an agricultural to an industrial base. Everything else was retained from the older depiction. The use of the three lions in the 1st quarter, namely the arms of the Kingdom of England, was sanctioned by Queen Elizabeth II. The lions along with Britannia, the supporter on the right, symbolize the bonds with the mother country and the British heritage of the city. The steamboat in the 4th quarter is meant to represent the paddle steamer Great Britain which plied the waters of Lake Ontario in the 1830s and was frequently seen in York harbour. The beaver, which was once a dominant symbol of Canada, represents industry, a word contained in the motto. The mural crown, built like a wall with battlements, frequently appears in the crest of civic arms.

The left supporter, pays homage to the Mississauga First Nation. It is simply described as: “a Mississauga Indian habited and accoutered and supporting in the dexter hand a bow …. all proper”. This description, like so many others of human supporters, does not tell us in any way what the attire looks like nor, apart from the bow, what the accoutrements might be. [31]

The left supporter, pays homage to the Mississauga First Nation. It is simply described as: “a Mississauga Indian habited and accoutered and supporting in the dexter hand a bow …. all proper”. This description, like so many others of human supporters, does not tell us in any way what the attire looks like nor, apart from the bow, what the accoutrements might be. [31]

Fig. 58. Armorial bearings granted to the City of Toronto by the English King of Arms on 29 December 1961. From Beddoe’s Canadian Heraldry (1981), p. 87, no 122.

The Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto, created in 1953, was granted arms on 17 July 1991 based on the original concept of the famous heraldists Alexander Scott Carter: https://www.gg.ca/en/heraldry/public-register/project/1527. After the amalgamation in 1997, the City of Toronto was granted new armorial bearings on 11 January 1999: https://www.gg.ca/en/heraldry/public-register/project/811. These arms are completely different from the former arms.

Wellington County

The arms of Wellington County were designed for a corporate seal in 1860 by the well-known Canadian heraldist Edward Marion Chadwick who blazoned them as: Gules, a cross between five plates in saltire in each quarter argent, all within a bordure of the last charged with eight garbs proper and for a crest a Field Marshall [sic] of England temp. George the Fourth, mounted, proper. [32] An 1860 impression of the seal shows the plates (silver roundels) to be in saltire in all four quarters as described by Chadwick. [33]

It seems that Chadwick’s seal design was reworked at a later date, sometime prior to the grant by Lord Lyon in 1984. Another description of the content of the seal corresponds to the image on the mug (fig. 59): Azure, a cross Gules between in dexter and sinister chief five pellets in saltire and in dexter and sinister base three pellets in bend and bend sinister, all within a bordure argent charged with seven garbs Or. [34]

The depiction on the cup (fig. 59) differs from Chadwick’s design in several ways. The field is now blue instead of red and the cross is red instead of white. Black roundels (pellets) rather than white ones occupy the four quarters and these, in the two lower quarters, are arranged in bend and bend sinister rather than being in saltire. The equestrian figure in the crest is now almost all gold rather than being in natural colours.

The arms of Wellington County were designed for a corporate seal in 1860 by the well-known Canadian heraldist Edward Marion Chadwick who blazoned them as: Gules, a cross between five plates in saltire in each quarter argent, all within a bordure of the last charged with eight garbs proper and for a crest a Field Marshall [sic] of England temp. George the Fourth, mounted, proper. [32] An 1860 impression of the seal shows the plates (silver roundels) to be in saltire in all four quarters as described by Chadwick. [33]

It seems that Chadwick’s seal design was reworked at a later date, sometime prior to the grant by Lord Lyon in 1984. Another description of the content of the seal corresponds to the image on the mug (fig. 59): Azure, a cross Gules between in dexter and sinister chief five pellets in saltire and in dexter and sinister base three pellets in bend and bend sinister, all within a bordure argent charged with seven garbs Or. [34]

The depiction on the cup (fig. 59) differs from Chadwick’s design in several ways. The field is now blue instead of red and the cross is red instead of white. Black roundels (pellets) rather than white ones occupy the four quarters and these, in the two lower quarters, are arranged in bend and bend sinister rather than being in saltire. The equestrian figure in the crest is now almost all gold rather than being in natural colours.

Fig. 59. Pottery coffee mug, illustrated with a version of the seal of Wellington County, prior to the grant of arms by Lord Lyon in 1984. Inscribed on bottom in relief MADE IN ENGLAND and stamped: "Country Town Tile Carleton Place, Canada".

The arms of Wellington County were recorded at the Court of the Lord Lyon in Edinburgh, Scotland on 19 September 1984 and blazoned: Azure a cross gules fimbriated argent between in each quarter five plates in saltire all within a bordure argent charged of seven garbs tenné and for a crest above a coronet composed of a circlet of eight points vert alternating with garbs or the circlet charged with eight maple leaves bendways or (four visible) on a wreath argent and azure a figure of the first Duke of Wellington holding a sword in his dexter hand and mounted on a horse passant proper. [35]

There are substantial differences between Chadwick’s blazon and that of the Scottish grant. The field and the cross are differently coloured and the equestrian crest figure is named specifically as the first Duke of Wellington. The Canadian Heraldic Authority registered the grant on 29 July 1996: https://www.gg.ca/en/heraldry/public-register/project/627. The coronet represents a county and the wheat sheaves symbolize an agricultural area. The motto is “Vision Valour”. Part of the contents of the shield, with colour modifications, come from the armorial bearings of the Duke of Wellington: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coat_of_Arms_of_the_Duke_of_Wellington.svg.

There are substantial differences between Chadwick’s blazon and that of the Scottish grant. The field and the cross are differently coloured and the equestrian crest figure is named specifically as the first Duke of Wellington. The Canadian Heraldic Authority registered the grant on 29 July 1996: https://www.gg.ca/en/heraldry/public-register/project/627. The coronet represents a county and the wheat sheaves symbolize an agricultural area. The motto is “Vision Valour”. Part of the contents of the shield, with colour modifications, come from the armorial bearings of the Duke of Wellington: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coat_of_Arms_of_the_Duke_of_Wellington.svg.

Windsor

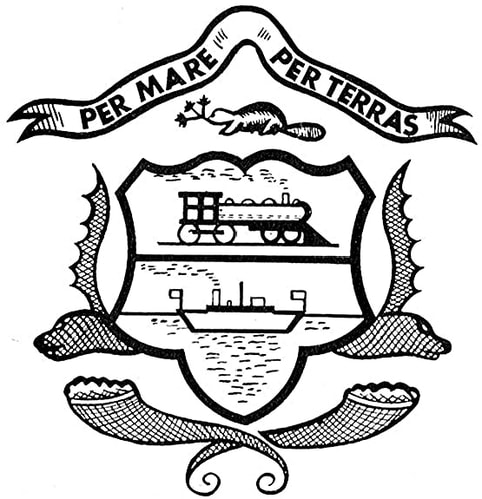

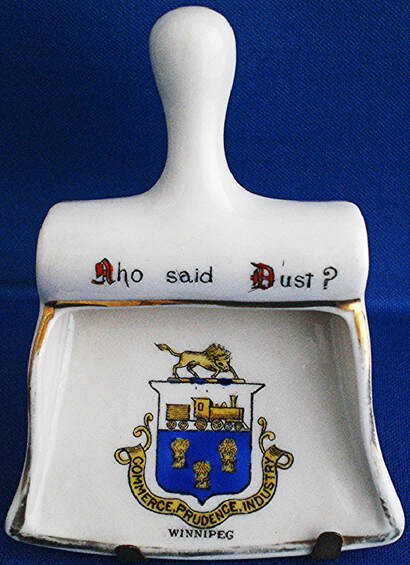

Chapin's description of the old arms of Windsor reads: “Per fess in chief a locomotive and in base a ferryboat. Crest: A beaver holding in his mouth a branch of tree twigs. Motto: ‘Per mare per terras’.”

The locomotive and ferryboat represent the importance of these two means of transportation in the city’s economy. They also echo to some extent the motto which translates “By Sea by Lands”. This motto is also that of several MacDonald and MacDonnell clans and may have some connection with an important member of the former clan such as the prominent businessman Colin MacDonald.[36] The placement of the motto on a scroll above the crest in the Scottish tradition supports this theory as well as the fact that Windsor is far away from the sea. Per Lacus Per Terram (By Lakes by Land) would have corresponded better to its geographical location.

In the crest the beaver with a sprig of maple in the mouth was an important symbol of Canada in the nineteenth century and in the early years of the twentieth century. It may also refer to the early fur trade in the area and to such fur traders as Alexander Duff who constructed the Duff-Baby House, an important historical monument in Windsor. [37] The beaver also frequently alludes to technical ability (building dams) and diligence. The supporters on the plate (fig. 60), a lion and a unicorn, are lifted directly from the royal arms and are no doubt chosen in connection with Windsor Castle which has been associated with British monarchs since William the Conqueror. There is no direct link with the House of Windsor which came into being on 17 July 1917, whereas the plate is dated 1907 from its Wedgwood mark. The two cornucopias on which they stand are symbols of abundance often related to agriculture.

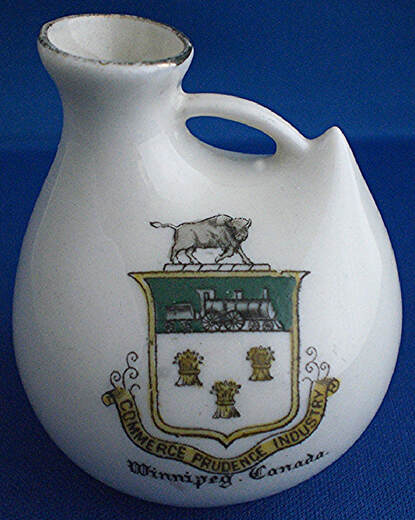

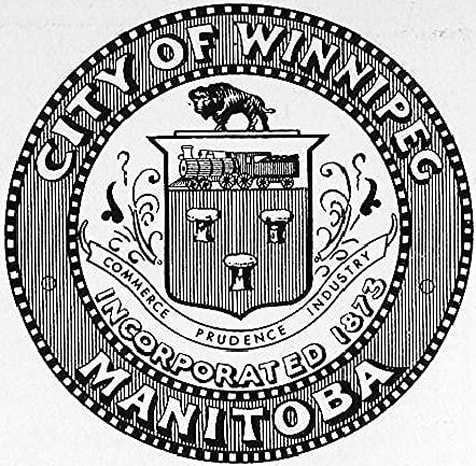

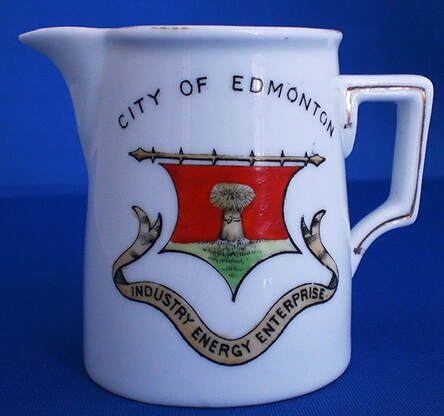

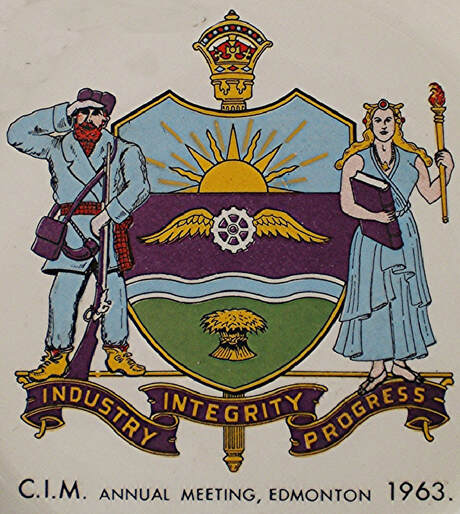

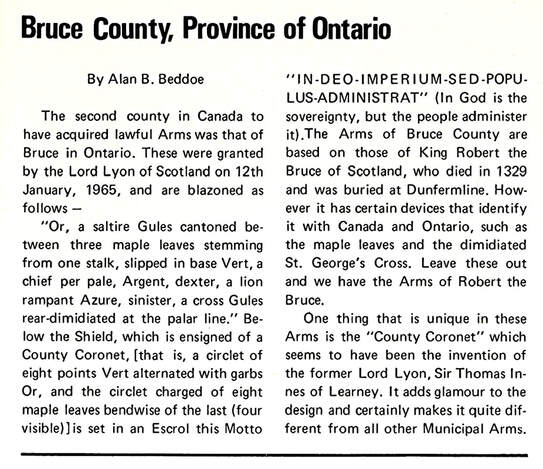

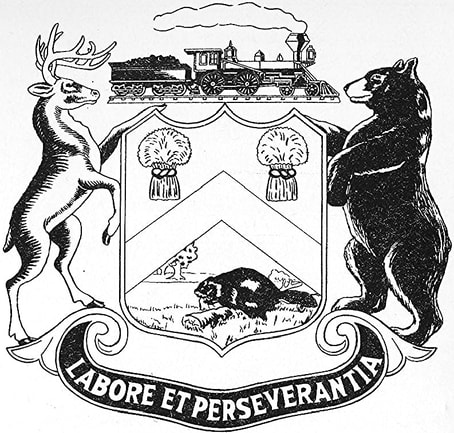

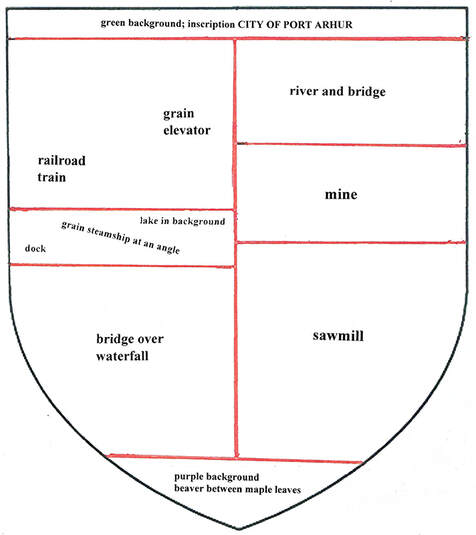

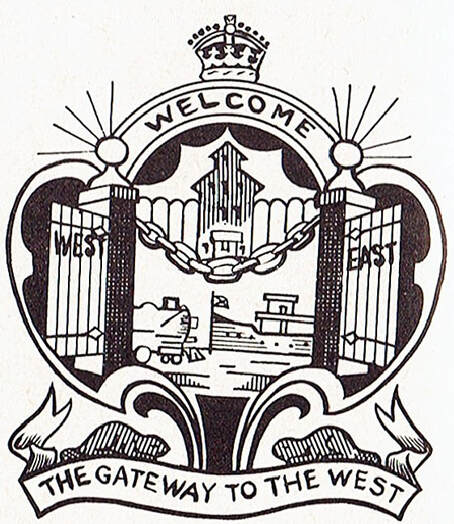

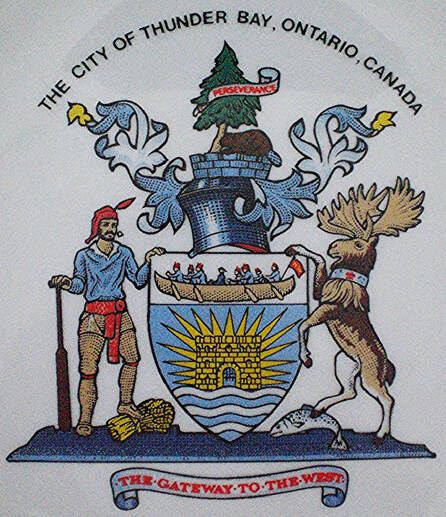

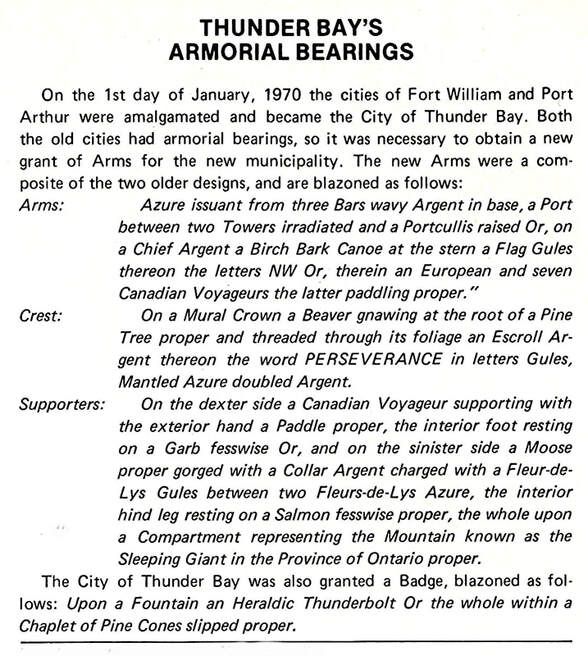

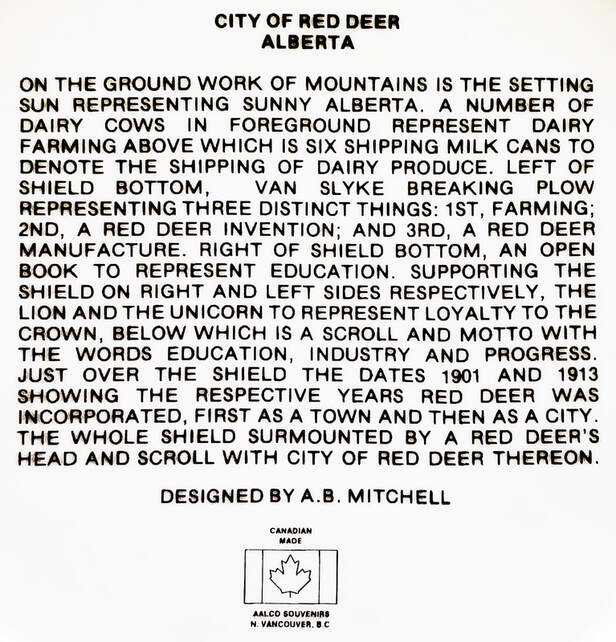

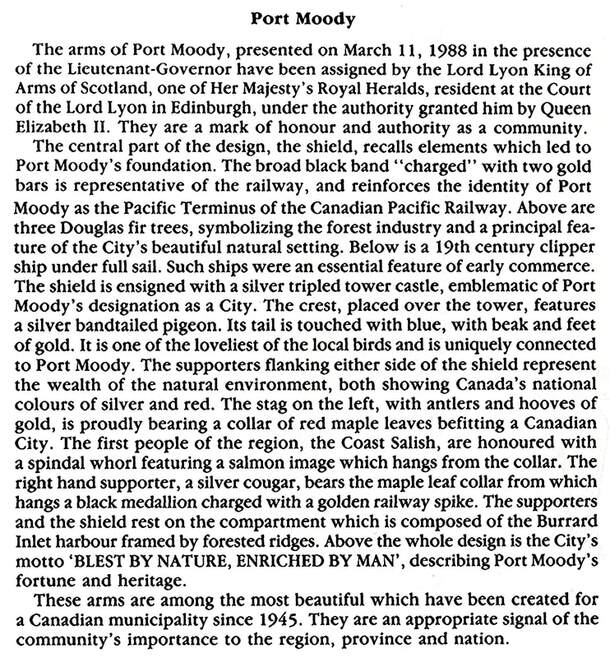

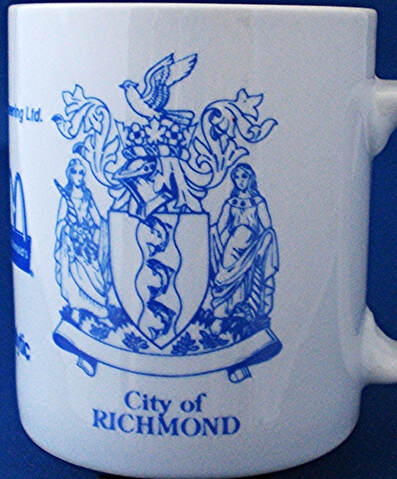

The Wedgwood plate must be one of the few examples of the old arms of Windsor depicted in colour since Chapin’s description in 1937 contains no colours. The design belongs by many aspects to the category I have sometimes dubbed the “Railroad, steamboat, river and canal” type inspired by Jim Reeves’ song and already quoted for the armorial device of Ottawa. Such arms often accumulate many elements and become very busy. This is not the case of the arms of Windsor where the shield displays only two items which convey a quaint and dynamic simplicity with its own appeal. The locomotive and steamboat are facing right (contourné) which is not the usual heraldic positioning but is something that happens in heraldry.