APPENDIX I

LEARNING TO BLAZON

Learning to blazon, that is to describe with specialized words the composition of a coat of arms, requires practice but need not be tedious as we shall see. Before attempting to blazon, one should have some notions of the components of a coat of arms, the tinctures used, the possible divisions of a shield, the various patterns that lines can form, and the main elements that appear on a shield, including the attitudes and attributes of various animals. An excellent book for this purpose is Kevin Greaves’ A Canadian Heraldic Primer which is readily available, presented clearly and concisely, and can be read in one sitting (see http://www.heraldry.ca/misc/publications_rhsc.htm). A Guide to blazonry by the same author is available online at http://education.heraldry.ca/BLAZONRY_GUIDE_2014.pdf. These two books should suffice as initial working tools. Many works provide more detailed information: Stephen Friar, A New Dictionary of Heraldry; also by Friar, Heraldry for the Local Historian and Genealogist; Boutell’s Heraldry revised by J.P. Brooke-Little; and Heather Child, Heraldic Design. The introduction of An Heraldic Alphabet, also by Brooke-Little, contains important general information, and more relevant to our purpose, “The Grammar of Heraldry,” a section devoted to the conventions of blazonry. Those wishing to deepen their knowledge of heraldry will want to look at “The Heraldry Proficiency Program” of the Royal Heraldry Society of Canada at http://www.heraldry.ca/top_en/top_exam.htm.

Blazoning need not be learned by rote as it can be mastered while doing blazoning exercises, which is the one sure way to learn the science of blazonry. What follows is concerned largely with some of the unusual situations that the student will inevitably encounter such as syntax complexities, situations where opinion is divided, problems for which the rules are not well defined, as well as long established conventions that are not specified in heraldic descriptions.

N.B. The sources of illustrations and blazons below that are identified by a name only are from the Hans D. Birk collection of arms at Library and Archives Canada, Beddoe’s Canadian Heraldry and Fox-Davies, The Art of Heraldry. Heraldic descriptions where no source is given are my own. In some cases, I have adjusted the capitalization and punctuation of existing blazons and removed archaic formulas for clarity and uniformity. All the web sites quoted here were accessed on 16 August 2015.

Blazoning need not be learned by rote as it can be mastered while doing blazoning exercises, which is the one sure way to learn the science of blazonry. What follows is concerned largely with some of the unusual situations that the student will inevitably encounter such as syntax complexities, situations where opinion is divided, problems for which the rules are not well defined, as well as long established conventions that are not specified in heraldic descriptions.

N.B. The sources of illustrations and blazons below that are identified by a name only are from the Hans D. Birk collection of arms at Library and Archives Canada, Beddoe’s Canadian Heraldry and Fox-Davies, The Art of Heraldry. Heraldic descriptions where no source is given are my own. In some cases, I have adjusted the capitalization and punctuation of existing blazons and removed archaic formulas for clarity and uniformity. All the web sites quoted here were accessed on 16 August 2015.

Fig. 1 von Woellwarth-Lauterburg, Birk, 474.

For a simple shield with only one figure, the first thing mentioned is the colour of the field, after which the main central figure is described. For fig. 1 it suffices to say Argent a crescent Gules. There is no need to specify the position of the crescent since its horns point upwards as they should do. The mantling or lambrequins on both sides of the helmet are almost always of the main colour and metal of the shield with the colour on the outside and the metal as the lining. The crest above the helmet is A crescent Gules issuant from a crown flory Or. Issuant means “coming out of” or “rising from;” flory means ending in or decorated with fleurs-de-lis.

The colours and metals are often capitalized in blazons except for proper, which means natural colours and the first, the second, etc., which applies to the first, second, etc., tinctures in the description. A capitalized Or (gold) cannot be mistaken for the conjunction or, but some heraldists advocate the avoidance of capitalization for any tincture. Formerly nouns were capitalized as well, but this seems unnecessary except for proper nouns. When several components in sequence are all of the same metal or colour, the tincture specified after the last item applies to all those that precede. The modern tendency is to avoid all punctuation in blazons, but there are times when a minimum of punctuation is needed to avoid ambiguities. For instance the crest of one officially granted coat of arms reads: “… upon a log of Maple fesswise sprouting a beaver proper.” Without a comma after sprouting, it sounds as if the beaver were sprouting from the log.

The colours and metals are often capitalized in blazons except for proper, which means natural colours and the first, the second, etc., which applies to the first, second, etc., tinctures in the description. A capitalized Or (gold) cannot be mistaken for the conjunction or, but some heraldists advocate the avoidance of capitalization for any tincture. Formerly nouns were capitalized as well, but this seems unnecessary except for proper nouns. When several components in sequence are all of the same metal or colour, the tincture specified after the last item applies to all those that precede. The modern tendency is to avoid all punctuation in blazons, but there are times when a minimum of punctuation is needed to avoid ambiguities. For instance the crest of one officially granted coat of arms reads: “… upon a log of Maple fesswise sprouting a beaver proper.” Without a comma after sprouting, it sounds as if the beaver were sprouting from the log.

Fig. 2 v. Innhausen-Knyphausen, Birk, 223.

Fig. 2 is also simple, but the position of the lion has to be specified. The blazon becomes Or a lion rampant Sable. The reader will have noticed that the claws and tongue of the lion are red and may ask why the expression armed and langued Gules is not included? For a lion this is a convention that need not be spelt out. If the lion were Or and the field Gules or vice-versa, the claws would be Azure, and this would also be understood. The crest topping the helmet is a little more complex than the shield. At first glance, one might think that a winged lion is involved, but the wings are too low. The proper description becomes A demi-lion Sable issuant between two wings addorsed the dexter one Or the sinister one Sable. Some heraldists would include the word rampant to describe the demi-lion, but this is often excluded as being obvious. The addorsed position of the wings is as if a bird were standing in profile, facing to the left of the spectator, with raised wings pointing to the sky. The left wing in front would then be fully seen and the right wing only in part at the back. The gold right wing at the back is mentioned first because the right takes precedent over the left in heraldry.

One important thing to know is the difference between dexter and sinister, which mean right and left in Latin. When these terms apply to the components of an achievement of arms, they are reversed with respect to the left and right of the spectator just as an image in a mirror. In the blazons that follow, the reader is encouraged to look up the terms that are unfamiliar. This can be done in various dictionaries or on the internet, for instance on the site: http://www.heraldsnet.org/saitou/parker/Jpglossa.htm.

One important thing to know is the difference between dexter and sinister, which mean right and left in Latin. When these terms apply to the components of an achievement of arms, they are reversed with respect to the left and right of the spectator just as an image in a mirror. In the blazons that follow, the reader is encouraged to look up the terms that are unfamiliar. This can be done in various dictionaries or on the internet, for instance on the site: http://www.heraldsnet.org/saitou/parker/Jpglossa.htm.

Fig. 3 von Becker, Birk, 192.

For fig. 3 the blazon seems at first glance: Vert a windmill Or, but on taking a closer look, one discovers that the windmill is seen from the back. The sails are not at the front as is normal. Then how is this expressed? A windmill Or seen from the back sounds a little prosaic. Seen a tergo sounds deliberately pedantic. The simplest description seems Vert a windmill Or sails inwards. The lesson to learn from this simple imagery is that it is always unusual combinations or positioning that are the most difficult to deal with, not shields with many divisions or quarters that present nothing unusual. The crest above the helmet could be blazoned: Ten stalks of wheat issuant from a coronet its rim Or jewelled Gules and Vert and heightened with four spikes tipped with trefoils Or. Trefoil means “three-leaved.”

Fig. 4 Howard Rokeby Rokeby-Thomas, Beddoe’s, 134.

Fig. 4 is blazoned “Or, on a chevron Vert between three Cornish choughs Sable a Maple leaf of the First” (Beddoe’s, p. 136). Some heraldists place a comma after the first tincture mentioned, but this seems unnecessary. Also there seems no compelling reason to capitalize “maple” and “first” even if the latter refers to the metal Or. The blazon would read much easier if it said a maple leaf Or instead of a Maple leaf of the First, a phrase which forces the reader to look back to see what the first tincture was. The reader may wonder why beaked and membered Gules is not mentioned for the Cornish choughs. Again it is a convention that they are always depicted with red bill and legs. In fact they are almost always described as proper. The blazon may seem inverted since what is on the chevron is mentioned last, but should it read Or a chevron Vert charged with a maple leaf Or between three Cornish choughs …, it would sound as if the choughs were on the chevron. If one opted for Or a chevron Vert charged with a maple leaf Or between three Cornish choughs Sable two in chief and one in base, everything would be clear, but six additional words would have been used, and blazonry is always seeking economy of words. The black hat with one tassel on each side is that of a Catholic priest.

Fig. 5 The Shawinigan Water and Power Company, Montreal, Beddoe’s, 118.

The blazon of fig. 5 is “Or, a Chevron Sable, charged with a Fork of Lightning Argent, in chief, two Fleurs de Lys Azure, in base a pair of demi-Horses, a Black and a White, issuant from Water undy of the Fourth and Third” (Beddoe’s, p. 121). Here many nouns are unnecessarily capitalized, and the formula “of the first, of the second,” etc. is used. Contrary to fig. 4, the lightning fork on the chevron is mentioned from the start, and with good reason. The inverted form would have given Or, on a chevron Sable between in chief, two Fleurs- de-Lys Azure, in base a pair of demi-Horses, a Black and a White, issuant from Water undy of the Fourth and Third, a Fork of Lightning Argent. This is not commendable because many things have been enumerated before the last item is mentioned, so that most readers have to read back to understand the relationship of the fork of lightning with the chevron. Because what is in chief is different from what is in base, the exact placement of the fleurs-de-lis and demi-horses has to be specified. They therefore cannot be confused as being on the chevron as when the three accompanying items are the same (fig. 4). The first blazon is best because it is more direct than the second and the number of words is the same in both.

There seems to be no valid reason for describing the demi-horses as black and white except for the notion of positive and negative polarity. But including symbolism in the heraldic description should be avoided because a blazon is the exact description of the arms. The significance of components should appear in a paragraph devoted to symbolism. This is also true of “water.” The fact that the wavy bars represent water should be in a symbolism section, not in the blazon. A shorter and more readable blazon, with no unnecessary capitalization and limited punctuation, would be: Or a chevron Sable charged with a fork of lightning Argent, in chief two fleurs-de-lys Azure, in base a pair of demi-horses, one Sable one Argent, issuant from barry wavy Azure and Argent.

There seems to be no valid reason for describing the demi-horses as black and white except for the notion of positive and negative polarity. But including symbolism in the heraldic description should be avoided because a blazon is the exact description of the arms. The significance of components should appear in a paragraph devoted to symbolism. This is also true of “water.” The fact that the wavy bars represent water should be in a symbolism section, not in the blazon. A shorter and more readable blazon, with no unnecessary capitalization and limited punctuation, would be: Or a chevron Sable charged with a fork of lightning Argent, in chief two fleurs-de-lys Azure, in base a pair of demi-horses, one Sable one Argent, issuant from barry wavy Azure and Argent.

Fig. 6 Joseph Ralph Harper, Beddoe’s, 130.

Counterchanged occurs when a figure placed on a divided field of several tinctures has its own tinctures reversed with respect to those of the field. Fig. 6 is described as Per fess Sable and Or a lion rampant counterchanged gorged with an eastern crown Gules and holding in the forepaws a harp Or; crest: A demi-lion per fess Or and Sable gorged with an eastern crown Gules holding in the forepaws a harp Or (Beddoe’s, p. 132, with adjustments). Counterchanged could occur with other lines of division such as per fess, per bend, per saltire or quarterly. Note the composition of the eastern crown, which is one of many crowns! For the crest a demi-lion as in the arms should have covered everything, but it is a complex image and the composer of the blazon may have felt that it was better to spell everything out rather than to leave the door open to confusion as to whether the lion was still wearing the crown and holding the harp. Specifying forepaws instead of just paws for the lion seems superfluous because this is the normal situation. If the harp was held in the hind paws, specifying such an unusual arrangement would be essential.

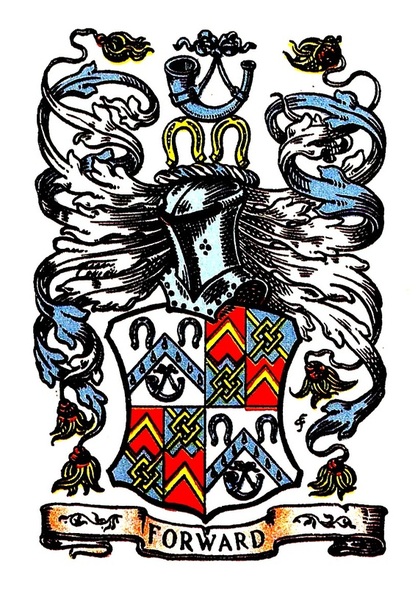

Fig. 7 Edward Garthwaite Farish, Fox-Davies, plate XXXII.

Shields can have many quarters and the quarters themselves can be quartered. Fig. 7 is blazoned – Arms: Quarterly 1 and 4, Argent a chevron Azure gutty d'eau between two horseshoes in chief and a bugle horn stringed in base Azure; 2 and 3, quarterly per fess indented, i and iv Gules, a chevron Or, ii and iii Azure a fret Or; Crest: Upon two horseshoes Or a bugle horn stringed Azure (Fox-Davies, p. 104, with adjustments). Quarters 1, 2, 3, 4 are grand quarters, i, ii, iii, iv are sub-quarters. We will see the term grand quarter included in the blazon of fig. 10. Gutty d’eau refers to drops of water, which are white. Drops of other coloration have specific names.

Fig. 8 Major Harry North, of Eltham, County Kent, Fox-Davies, plate XXIV.

Fig. 8 is blazoned – Arms: Argent two chevronels nebuly between two mullets in chief and a decrescent in base Sable impaling the arms of Evans Or a dragon Sable, in chief three roses Gules slipped and leaved proper and in base a fleur-de-lis also Gules; Crest: on a wreath of the colours a lion’s head erased Argent gorged with a collar nebuly and between two mullets Sable (Fox-Davies, p. 79, adjusted). Note that Sable comes last in the arms of Major North and applies to all the preceding charges.

To impale two arms means placing them side by side on one shield to indicate man and wife or to bring together individual arms with those of office such as the personal arms of a bishop impaling those of the diocese, or a rector’s personal arms impaling those of a university. Another way of bringing two arms together is dimidiation, which involves cutting two arms in half vertically and fusing them together on one shield (fig. 9).

To impale two arms means placing them side by side on one shield to indicate man and wife or to bring together individual arms with those of office such as the personal arms of a bishop impaling those of the diocese, or a rector’s personal arms impaling those of a university. Another way of bringing two arms together is dimidiation, which involves cutting two arms in half vertically and fusing them together on one shield (fig. 9).

Fig. 9 Hastings arms, on miniature flour scoop with Gemma mark by Schmidt & Co., Czechoslovakia, ca. 1925, property of A. & P. Vachon.

The arms of the Cinque Ports are as follows Gules three lions passant guardant Or (England) dimidiating Azure three ships’ hulls fesswise in pale Argent. This means that the front halves of the lions are fused to the sterns of the ships. The arms of Hastings (fig. 9), one of the Cinque Ports, are somewhat different in that the lion in fess is not cut in half. They can be described as Party per pale Gules and Azure a lion passant guardant Or between, in chief and in base, a lion passant guardant Or dimidiated with the hull of a ship Argent (after Fox-Davies, The Book of Public Arms, p. 356-57). This is the type of unusual composition which can require a long time to put together.

Fig. 10 Col. Albert Cantrell Cantrell-Hubbersty of Tollerton Hall, Fox-Davies, plate XLIV.

Some blazons can become quite tedious to deal with because of sheer quantity. Sometimes, after the blazon of a quarter, the name of the family to which it belongs is mentioned. If the quarter is repeated elsewhere in the arms, only the name of the family need be mentioned as we shall see. Fig. 10 is blazoned Quarterly, first grand quarter, quarterly 1 and 4, Vert, two bars engrailed between two moles erect in chief, and in base a griffin’s head erased all Or (for Hubbersty); 2and 3, Argent, a pelican in her piety, in chief two roses, the whole within as many flaunches all Sable (for Cantrell); second grand quarter, Hubbersty; third grand quarter, Cantrell; fourth grand quarter, Or a pile Azure, over all a chevron invected between two garbs in chief and in base a mullet of six points all counterchanged (for Boultbee); impalling Or two bars Gules goutty d’Or, in chief a cross couped Gules between two leopards’ faces and in base a lion rampant Sable (for Jessop). Crests - 1. Upon a wreath of the colours, in front of a griffin’s head erased Argent, charged with a fess engrailed Vert, a mole fesswise Or (for Hubbersty); 2. Upon a wreath of the colours, in front of a tower Argent, a rock proper, thereon a boar passant Sable, armed Or charged on the body with two roses Argent (for Cantrell), [adapted from Fox-Davies, Armorial Families, vol. 1, p. 306 and vol. 2, p. 1055] .

For many words there is a French equivalent, such as goutté for goutty, and several different spellings. All are acceptable, but consistency is important. For instance one should not combine goutté with semy (strewn) in the same blazon. Preferring French forms or the most unusual spellings when blazoning in English appears to reflect some degree of eccentricity. The expression in front of appears particularly in crests where something surmounts or charges the main element although not in the centre as these terms imply, but on the crest wreath, see http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=2512&ShowAll=1. In front of is also used at times to describe the imagery on a shield, see http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=930&ShowAll=1.

Col. Albert Cantrell (1843-1915) married Martha Lydia Jessop on 5 December 1876, which explains the impalement of his arms with those of his wife. This impalement creates an aesthetic imbalance. His own elaborate arms are crowded on one side while those of his wife seem a little elongated, but this is the type of situation that combinations of arms on one shield (marshalling) can create.

For many words there is a French equivalent, such as goutté for goutty, and several different spellings. All are acceptable, but consistency is important. For instance one should not combine goutté with semy (strewn) in the same blazon. Preferring French forms or the most unusual spellings when blazoning in English appears to reflect some degree of eccentricity. The expression in front of appears particularly in crests where something surmounts or charges the main element although not in the centre as these terms imply, but on the crest wreath, see http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=2512&ShowAll=1. In front of is also used at times to describe the imagery on a shield, see http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=930&ShowAll=1.

Col. Albert Cantrell (1843-1915) married Martha Lydia Jessop on 5 December 1876, which explains the impalement of his arms with those of his wife. This impalement creates an aesthetic imbalance. His own elaborate arms are crowded on one side while those of his wife seem a little elongated, but this is the type of situation that combinations of arms on one shield (marshalling) can create.

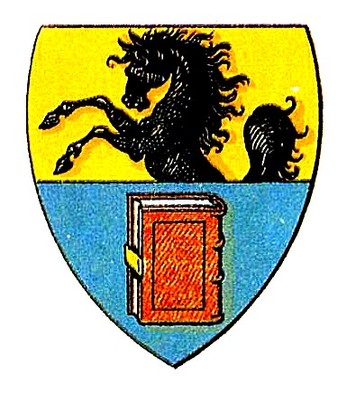

Fig. 11 Literary Union of Stuttgart, Fox-Davies, plate CXXII.

The description of fig. 11 is normal, namely Party per fess Or and Azure, in chief a demi-mare issuant Sable, in base a closed book Gules (original in Fox-Davies, p. 447, no. 14). The shield is divided horizontally in half. Issuant in chief means coming out of the partition line below.

Fig. 12 German School Union in Austria, Fox-Davies, plate CXXII.

Fig. 12 presents a special case Per fess Sable and Or a fess Gules, issuant from base onto the fess a sprig of oak Vert fructed [of two] Or, in chief a demi-sun in splendour issuant also Or (blazoned differently in Fox-Davies, p. 447, no. 12). Normally a charge is placed on another figure, surmounts it, that is extends over it, or is placed overall, that is over everything. Here it extends over both the base and fess without being overall, which is unusual. The blazon in Fox-Davies did not correspond entirely to the image. My own description may look easy once done, but, although I have many years of experience in blazoning, I had to try several combinations before arriving at the one I deemed easy to read and clear. In such cases, one is never sure that the best wording has been achieved, but the description must be rigorously accurate to permit an exact rendering. As previously mentioned, it is not the shields with many divisions and quarters that are the most difficult to blazon, but unusual situations which may require many trials to get the wording right and make the blazon sound heraldic. I repeated “also Or” for the sun to prevent any ambiguity, although it is generally understood that everything that precedes a tincture is of that tincture. This is a matter of judgement. Some artist use Gold to avoid repeating Or. For the acorns, I placed [of two] in brackets after fructed because it is usually better to leave the number of acorns like the number of leaves to the artist. However, if there is a special symbolism attached to the number two, it is necessary to specify this number in the blazon.

Fig. 13 Sir James Strangwayes, Fox-Davies, plate XCIX, p. 428, no. 4.

The arms of Sir James Strangwayes (fig. 13) are not difficult to blazon once the onlooker realizes what is going on: Sable two lions passant in pale, paly of six Argent and Gules [armed and langued Or] (original blazon, Fox-Davies, p. 428, no. 4). The tongue and claws of the lions would normally have been red, but this would not have created a clear demarcation with the parts where the lions are also red. Blue would also have been appropriate. In such cases, the tincture can be mentioned, but it is usually best to leave such details to the artist rather than specifying them in the blazon.

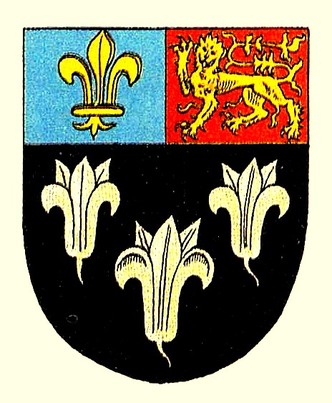

Fig. 14 Eton College, Fox-Davies, plate CXXII.

The arms of Eton College (fig. 14) contain both a fleur-de-lis and a lily of the Easter type. Fox-Davies offers the following description “Sable, three (natural) lilies argent, a chief party per pale azure and gules, charged on the dexter side with a fleur-de-lis and on the sinister with a lion passant guardant or” (Fox-Davies, p.447, no. 18) The word natural is added to lily to prevent confusion with the fleur-de-lis, but this is not essential because the two words are entirely different. Both are clearly defined in heraldic dictionaries and drawn with their own stylization. Should the fear of confusion persist, the Latin designation (Lilium candidum) could be added to the natural lily. Similarly the heraldic dolphin is a specific creature with little to do with a real dolphin. If the latter is intended, the specific Latin name such as (Tursiops truncates) should appear, unless the person blazoning wants to leave the door open for both types of representations. The same would be true of the heraldic tiger as opposed to the real one.

The possibility of confusion between homonyms is often only apparent. A heraldic fountain is a roundel barry wavy Argent and Azure that is usually designated simply as a fountain without mentioning tinctures. In good blazoning there can be no confusion with a natural fountain because, the moment a tincture is added, it becomes obvious that a real fountain is intended. The Hotel Association of Canada contains “two Fountains Or and Gules” (Beddoe’s, p. 117, no. 174). This wording creates confusion with a natural fountain for no valid reason and runs counter to the definition of the heraldic fountain. Blazoning two roundels barry wavy Or and Gules would have been correct and much clearer.

More problematic is the way to describe the water if it is of a different colouration than the fountain itself. To find how this could be worded, I consulted several works, of which Fairbairn’s Crests was the most helpful. A fountain Argent with water Azure could be described in several ways. A fountain Argent throwing up water Azure is very clear but not very heraldic sounding. A fountain Argent playing Azure is a very poetic designation, which should no doubt be encouraged since it sounds as if the water was playing music. One reservation is that the term has not yet become standard terminology. Another solution is to resort to ordinary words such as A fountain Argent gurgling (or spouting) Azure. If a fountain appears in heraldry as an historic or important monument, its name and location should be specified.

The possibility of confusion between homonyms is often only apparent. A heraldic fountain is a roundel barry wavy Argent and Azure that is usually designated simply as a fountain without mentioning tinctures. In good blazoning there can be no confusion with a natural fountain because, the moment a tincture is added, it becomes obvious that a real fountain is intended. The Hotel Association of Canada contains “two Fountains Or and Gules” (Beddoe’s, p. 117, no. 174). This wording creates confusion with a natural fountain for no valid reason and runs counter to the definition of the heraldic fountain. Blazoning two roundels barry wavy Or and Gules would have been correct and much clearer.

More problematic is the way to describe the water if it is of a different colouration than the fountain itself. To find how this could be worded, I consulted several works, of which Fairbairn’s Crests was the most helpful. A fountain Argent with water Azure could be described in several ways. A fountain Argent throwing up water Azure is very clear but not very heraldic sounding. A fountain Argent playing Azure is a very poetic designation, which should no doubt be encouraged since it sounds as if the water was playing music. One reservation is that the term has not yet become standard terminology. Another solution is to resort to ordinary words such as A fountain Argent gurgling (or spouting) Azure. If a fountain appears in heraldry as an historic or important monument, its name and location should be specified.

Fig. 15 Arms of the City of Guelph, on a plate decorated by Canadian Art China, Collingwood, Ontario, property of A. & P. Vachon.

The arms of the City of Guelph (Ontario) offer an opportunity to look at a full achievement of arms having arms, crest, mantling, supporters and a motto (fig. 15). The compartment on which the supporters stand is described with the supporters. Unnecessary capitalization has been avoided (also blazoned in Beddoe’s, p. 184 and http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1547&ProjectElementID=5179).

Arms: Argent on a fess Gules cotised Vert between three ancient crowns Gules a horse courant Argent.

Crest: Within an ancient crown Gules a mount Vert thereon a lion statant Or anciently crowned Gules resting the dexter forepaw upon the haft of an axe head downwards and inwards proper.

Mantling: Gules doubled Argent and Or.

Supporters: Upon a grassy mount with on the dexter side in front of a copse a felled tree trunk lying to the dexter, in the stock an axe proper in front of the same a man with a hat, open shirted, in breeches and boots proper vested of a tail coat cut away Gules, on the sinister a female figure proper vested Argent cloaked Azure wearing a helmet Or crested Gules supporting with the dexter arm a trident points upward Sable and holding by the sinister hand by the point a cornucopia proper.

Motto: Faith . Fidelity . Progress.

The first thing to mention regarding the arms is the expression cotised Vert. This means that the central element, the fess has cotises, that is a narrow band above and below. It also seems worthwhile to again draw attention to the heraldic syntax. After mentioning the fess the blazon describes everything else on the outside and finally mentions the white horse courant (running, an attitude) on the fess. If the blazon were Argent on a fess Gules cotised Vert a horse courant Argent between three ancient crowns Gules, this would create the impression that the crowns were also on the fess―see the blazon for fig. 4. The ancient crowns shown here alternate a three-leaved (trefoil) pattern on a plain rim; other ancient crowns alternate fleurs-de-lis.

The crest is fairly straightforward. The lion is statant (stopped, standing on all fours) which is again an attitude. It is also customary to designate precisely the position of tools and weapons when they are not in their conventional position. For example an axe on a shield would have the blade upwards and the cutting edge to the dexter. The mantling is lined by two metals, Argent and Or.

Supporters are rarely described with as much details as here. The man represents John Galt who felled the first tree for the settlement in 1827. It would be bad form to describe him as John Galt in 1827, but the description could well have been “an Upper Canada gentleman ca. 1827.” Describing the costume in many details has its drawbacks. If a specialist should find out that the costume is not correct for the period, a more general description would allow changes to the depiction without contravening the blazon. On the depiction above, the coat is not red, as specified by the blazon, but brown―compare with the image on http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1547&ProjectElementID=5179. Note that proper appears at almost half of the description of the supporters and refers to everything preceding.

Arms: Argent on a fess Gules cotised Vert between three ancient crowns Gules a horse courant Argent.

Crest: Within an ancient crown Gules a mount Vert thereon a lion statant Or anciently crowned Gules resting the dexter forepaw upon the haft of an axe head downwards and inwards proper.

Mantling: Gules doubled Argent and Or.

Supporters: Upon a grassy mount with on the dexter side in front of a copse a felled tree trunk lying to the dexter, in the stock an axe proper in front of the same a man with a hat, open shirted, in breeches and boots proper vested of a tail coat cut away Gules, on the sinister a female figure proper vested Argent cloaked Azure wearing a helmet Or crested Gules supporting with the dexter arm a trident points upward Sable and holding by the sinister hand by the point a cornucopia proper.

Motto: Faith . Fidelity . Progress.

The first thing to mention regarding the arms is the expression cotised Vert. This means that the central element, the fess has cotises, that is a narrow band above and below. It also seems worthwhile to again draw attention to the heraldic syntax. After mentioning the fess the blazon describes everything else on the outside and finally mentions the white horse courant (running, an attitude) on the fess. If the blazon were Argent on a fess Gules cotised Vert a horse courant Argent between three ancient crowns Gules, this would create the impression that the crowns were also on the fess―see the blazon for fig. 4. The ancient crowns shown here alternate a three-leaved (trefoil) pattern on a plain rim; other ancient crowns alternate fleurs-de-lis.

The crest is fairly straightforward. The lion is statant (stopped, standing on all fours) which is again an attitude. It is also customary to designate precisely the position of tools and weapons when they are not in their conventional position. For example an axe on a shield would have the blade upwards and the cutting edge to the dexter. The mantling is lined by two metals, Argent and Or.

Supporters are rarely described with as much details as here. The man represents John Galt who felled the first tree for the settlement in 1827. It would be bad form to describe him as John Galt in 1827, but the description could well have been “an Upper Canada gentleman ca. 1827.” Describing the costume in many details has its drawbacks. If a specialist should find out that the costume is not correct for the period, a more general description would allow changes to the depiction without contravening the blazon. On the depiction above, the coat is not red, as specified by the blazon, but brown―compare with the image on http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1547&ProjectElementID=5179. Note that proper appears at almost half of the description of the supporters and refers to everything preceding.

While humans are not mentioned by name generally, gods, archangels, saints and mythical figures are. In the case of the female figure, stating that it is the figure of Britannia proper would have been more in keeping with heraldry and would have eliminated the necessity of describing all her clothes and accoutrements, except the horn of plenty which is not usually associated with her but with Ceres, the goddess of agriculture and cereals. The words holding by the sinister hand by the point a cornucopia could have been replaced simply by holding by the sinister hand a cornucopia. Sometimes all the produce of a cornucopia are spelt out. Here all this is covered by proper, which is the right thing to do. As a rule, it is commendable to leave such details to the discretion of the artist. In this case, if an artist were called upon to reconstruct the horn of plenty from the description, it would be necessary to find out what is grown in the Guelph area, but this is easy enough particularly with the Web. This inquiry could allow an update if the agricultural base of the region had changed.

A good blazon is crisp, flows and sounds well. It cannot be a juxtaposition of words that fails to convey a clear image and is therefore useless, since the purpose of a blazon is to allow any artist to reconstruct the essential features of the original arms at anytime in the near or distant future. Style will vary from one artist to the next, but the essential components should remain the same. Before finalizing the blazon of a new creation, put yourself in the position of the artist to see if you can reproduce the imagery from the description. If in doubt, ask someone knowledgeable in heraldry to attempt this.

A person learning to write inevitably uses too many words. The same is true of the budding heraldists. After constructing a blazon, one should look at it closely to eliminate any useless words. Even experienced heraldists can fall into the verbiage trap. If a blazon sounds complicated and fussy and does not flow well, there should be a simpler way of arriving at a better-sounding description, although clarity is paramount even if additional words and resorting to ordinary vocabulary is required. Blazoning can involve a long and exacting session of trial and error. Quite often an emblem is difficult to describe because the design is flawed, but this is not always the case. A simple but unusual design can also present challenges.

As we have already seen, over-describing can present an obstacle for the artist. For instance, if a lion rampant holds a sword in its dexter paw, it is not necessary to state the precise angle of the sword by adding “in bend sinister”. Adding this would mean that the sword should be held at almost exactly a 45o angle, which could be an impediment to artistic expression. In such cases, it is much better to avoid being too specific and to let the artist decide what angle works best according to space constraints and the effect being sought.

Even if one learned all the vocabulary, grammar and declensions in a language, that person would still have to learn to speak and write by practicing. The same is true of blazoning. The easiest and surest way of learning this skill is to describe the arms on your own from the illustration without looking at the description, and then to compare your results with the written description. The reverse operation is to read blazons and reconstruct the image in one’s mind, or preferably as a quick sketch with colour abbreviations (tricking), and to compare the results with the actual depiction. For anyone anxious to learn, these are challenging and exciting drills, and a fun and sure way to acquire blazoning skills. In time the student will want to take a critical look at existing blazons.

The most useful tool for heraldic exercises is undoubtedly the Public Register of Arms Flags and Badges of Canada, now available on the Web. In the Public Register, Canadian heraldic words will come up. These terms are defined in Kevin Greaves and Donald S. Williamson The Canadian Heraldic Dictionary at: http://education.heraldry.ca/dictionary/canadian_heraldic_dictionary.htm. Other useful published works for this purpose are Joseph Foster’s, The Dictionary of Heraldry…, which contains both blazons and colour illustrations, and Beddoe’s Canadian Heraldry revised by Col. Strome Galloway, which is good for both simpler and full achievements of arms. Although many of the illustrations in Fox-Davies The Art of Heraldry are in black and white, they can still be very helpful because, as frequently emphasized, the problems that arise in blazoning are not tinctures but unusual combinations or positioning.

Blazoning is an essential step towards the mastery of heraldic science. By assiduously doing the exercises described above, the student will soon learn to recognize the main components of an achievement of arms, the divisions, the figures most frequent in heraldry, the structure of a blazon and the rhythm of heraldic language. If difficulties arise in blazoning entirely new creations, it usually helps to search for analogous situations in illustrated heraldic works.

A good blazon is crisp, flows and sounds well. It cannot be a juxtaposition of words that fails to convey a clear image and is therefore useless, since the purpose of a blazon is to allow any artist to reconstruct the essential features of the original arms at anytime in the near or distant future. Style will vary from one artist to the next, but the essential components should remain the same. Before finalizing the blazon of a new creation, put yourself in the position of the artist to see if you can reproduce the imagery from the description. If in doubt, ask someone knowledgeable in heraldry to attempt this.

A person learning to write inevitably uses too many words. The same is true of the budding heraldists. After constructing a blazon, one should look at it closely to eliminate any useless words. Even experienced heraldists can fall into the verbiage trap. If a blazon sounds complicated and fussy and does not flow well, there should be a simpler way of arriving at a better-sounding description, although clarity is paramount even if additional words and resorting to ordinary vocabulary is required. Blazoning can involve a long and exacting session of trial and error. Quite often an emblem is difficult to describe because the design is flawed, but this is not always the case. A simple but unusual design can also present challenges.

As we have already seen, over-describing can present an obstacle for the artist. For instance, if a lion rampant holds a sword in its dexter paw, it is not necessary to state the precise angle of the sword by adding “in bend sinister”. Adding this would mean that the sword should be held at almost exactly a 45o angle, which could be an impediment to artistic expression. In such cases, it is much better to avoid being too specific and to let the artist decide what angle works best according to space constraints and the effect being sought.

Even if one learned all the vocabulary, grammar and declensions in a language, that person would still have to learn to speak and write by practicing. The same is true of blazoning. The easiest and surest way of learning this skill is to describe the arms on your own from the illustration without looking at the description, and then to compare your results with the written description. The reverse operation is to read blazons and reconstruct the image in one’s mind, or preferably as a quick sketch with colour abbreviations (tricking), and to compare the results with the actual depiction. For anyone anxious to learn, these are challenging and exciting drills, and a fun and sure way to acquire blazoning skills. In time the student will want to take a critical look at existing blazons.

The most useful tool for heraldic exercises is undoubtedly the Public Register of Arms Flags and Badges of Canada, now available on the Web. In the Public Register, Canadian heraldic words will come up. These terms are defined in Kevin Greaves and Donald S. Williamson The Canadian Heraldic Dictionary at: http://education.heraldry.ca/dictionary/canadian_heraldic_dictionary.htm. Other useful published works for this purpose are Joseph Foster’s, The Dictionary of Heraldry…, which contains both blazons and colour illustrations, and Beddoe’s Canadian Heraldry revised by Col. Strome Galloway, which is good for both simpler and full achievements of arms. Although many of the illustrations in Fox-Davies The Art of Heraldry are in black and white, they can still be very helpful because, as frequently emphasized, the problems that arise in blazoning are not tinctures but unusual combinations or positioning.

Blazoning is an essential step towards the mastery of heraldic science. By assiduously doing the exercises described above, the student will soon learn to recognize the main components of an achievement of arms, the divisions, the figures most frequent in heraldry, the structure of a blazon and the rhythm of heraldic language. If difficulties arise in blazoning entirely new creations, it usually helps to search for analogous situations in illustrated heraldic works.