Chapter 4

One Resolute Man

Martin Burrell, secretary of state, and Thomas Mulvey, under-secretary of state, prepared a report dated 19 February 1919 which recommended the appointment of a committee to study “the advisability of requesting His Majesty the King, through the College of Heralds, for an amendment to the Armorial Bearings of Canada.” The report was conveyed through the Privy Council to the governor general who approved it on March 26. As had been proposed earlier by Thomas Mulvey, the committee was composed of himself, Joseph Pope, under-secretary of state for External Affairs, Arthur G. Doughty, Dominion Archivist, and Major-General Willoughby G. Gwatkin of the Department of Militia and Defence.

At the first meeting of the committee on April 3, Mulvey was appointed chairman and Doughty secretary. Although considerable advice and suggestions had already been received from the public on the question of arms for Canada, the committee decided to openly invite proposals. It opted for the inclusion of royal supporters, regarding which Pope was to communicate with Ambrose Lee, York Herald of Arms, to see if this was acceptable.[1] Pope was the senior member of the committee and the most experienced at negotiating arms. As under-secretary of state, he had obtained arms for Manitoba, Prince Edward Island, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. He was decisive and could exercise leadership, but the responsibility to negotiate arms was traditionally that of the secretary of state, and this was likely the reason for Mulvey's appointment as chairman.

Popes Memoirs convey a clearer idea of the actual discussions which took place at the first meeting. From them, we learn that the aggregate of provincial arms was completely rejected in favour of distinct arms which would include: 1) The Monarchical principle; 2) The French Regime and 3) Something Canadian such as the maple leaf.[2]

Gwatkin, who had been absent from the first meeting, wrote Mulvey assuring him that he concurred with the committee's decision and added: “Personally, I should like to see on a shield argent nine maple leaves arranged (small sketch of a cross formation): suggesting - 1. St. George (England) 2. The nine provinces. 3. Canada and her roll of honour. Other devices (the fleur de lys, for example) could be introduced, somehow. As an alternative motto to ‘A mari usque ad mare’ I suggest ‘In memoriam, in spem’.” (In remembrance, in hope).[3]

Of all the committee members, Gwatkin seemed to be the only one who was pushing for a preponderance of Canadian symbols. This was in line with Fiset’s earlier proposal (chapter 3) of which Gwatkin, as his delegate, was at least aware and may well have helped to prepare. Nine maple leaves had been one of Fiset’s proposals, and like Fiset, Gwatkin also considered a unique red maple leaf. He knew that a red maple leaf had been the badge of the Canadian Expeditionary Force during World War I and had written to Herbert George Todd, a genealogist and heraldist living in Yonkers (New York), to ask if the use of the maple leaf as a Canadian badge precluded its inclusion in the shield of arms of Canada. Todd replied that he was sure it did not and went on to preach the value of simplicity in matters of heraldry stating that: “a child should be able to draw the Canadian coat of arms in the dark.”

Yet when Lieut. Col. Charles Frederick Hamilton of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police did propose to Todd a single red maple leaf on a white field, he considered this to be too simple, too much like a badge. He much preferred Hamilton’s second suggestion of nine red maple leaves on white, particularly if arranged in the form of a St. George's cross as Gwatkin had suggested. In Todd’s mind, a badge was a quick means of identification and should be in the simplest form. On the other hand, a coat of arms was required to tell a story about its user and, in his view, should be a little more complex: “The badge should be universal, it is simply a mark as it were that sinks into the mind and requires no thinking about it while ...the banner on the shield [a shield and a banner of the arms contain the same components] was a sort of ‘who’s who’ which told the herald more than a little about the bearer.” Interestingly, the Gwatkin-Hamilton proposals all favoured red and white which would eventually become Canada's colours. Hamilton, a staunch royalist who had proposed that Canada be made a kingdom, obviously understood that the maple leaf and crown would make a viable combination.

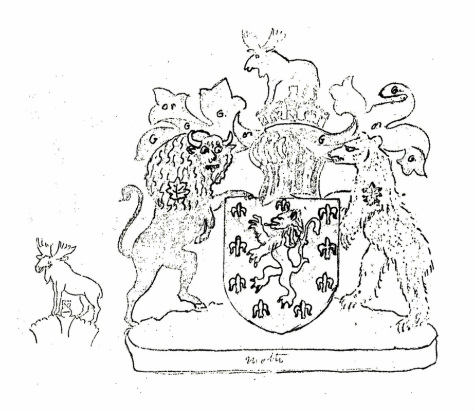

Todd recognized that the maple leaf was becoming increasingly popular and presented a beautiful simplicity, but he felt that the single leaf did not reveal enough and did not have sufficient history being “of very recent growth as a national symbol.”[4] To the maple leaf, he preferred symbols of the mother countries on the shield and proposed to Mulvey, as he had done to Hamilton, a red shield with a gold lion rampant in the centre surrounded by nine gold fleurs-de-lis, he added a helmet and crest in the form of a black moose, with golden horns and hooves, standing on the imperial crown. The supporters were, on the spectators left, a bison and, on the right, a polar bear, both in natural colours and adorned on the shoulder with a gold maple leaf (fig. 1).[5]

At the first meeting of the committee on April 3, Mulvey was appointed chairman and Doughty secretary. Although considerable advice and suggestions had already been received from the public on the question of arms for Canada, the committee decided to openly invite proposals. It opted for the inclusion of royal supporters, regarding which Pope was to communicate with Ambrose Lee, York Herald of Arms, to see if this was acceptable.[1] Pope was the senior member of the committee and the most experienced at negotiating arms. As under-secretary of state, he had obtained arms for Manitoba, Prince Edward Island, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. He was decisive and could exercise leadership, but the responsibility to negotiate arms was traditionally that of the secretary of state, and this was likely the reason for Mulvey's appointment as chairman.

Popes Memoirs convey a clearer idea of the actual discussions which took place at the first meeting. From them, we learn that the aggregate of provincial arms was completely rejected in favour of distinct arms which would include: 1) The Monarchical principle; 2) The French Regime and 3) Something Canadian such as the maple leaf.[2]

Gwatkin, who had been absent from the first meeting, wrote Mulvey assuring him that he concurred with the committee's decision and added: “Personally, I should like to see on a shield argent nine maple leaves arranged (small sketch of a cross formation): suggesting - 1. St. George (England) 2. The nine provinces. 3. Canada and her roll of honour. Other devices (the fleur de lys, for example) could be introduced, somehow. As an alternative motto to ‘A mari usque ad mare’ I suggest ‘In memoriam, in spem’.” (In remembrance, in hope).[3]

Of all the committee members, Gwatkin seemed to be the only one who was pushing for a preponderance of Canadian symbols. This was in line with Fiset’s earlier proposal (chapter 3) of which Gwatkin, as his delegate, was at least aware and may well have helped to prepare. Nine maple leaves had been one of Fiset’s proposals, and like Fiset, Gwatkin also considered a unique red maple leaf. He knew that a red maple leaf had been the badge of the Canadian Expeditionary Force during World War I and had written to Herbert George Todd, a genealogist and heraldist living in Yonkers (New York), to ask if the use of the maple leaf as a Canadian badge precluded its inclusion in the shield of arms of Canada. Todd replied that he was sure it did not and went on to preach the value of simplicity in matters of heraldry stating that: “a child should be able to draw the Canadian coat of arms in the dark.”

Yet when Lieut. Col. Charles Frederick Hamilton of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police did propose to Todd a single red maple leaf on a white field, he considered this to be too simple, too much like a badge. He much preferred Hamilton’s second suggestion of nine red maple leaves on white, particularly if arranged in the form of a St. George's cross as Gwatkin had suggested. In Todd’s mind, a badge was a quick means of identification and should be in the simplest form. On the other hand, a coat of arms was required to tell a story about its user and, in his view, should be a little more complex: “The badge should be universal, it is simply a mark as it were that sinks into the mind and requires no thinking about it while ...the banner on the shield [a shield and a banner of the arms contain the same components] was a sort of ‘who’s who’ which told the herald more than a little about the bearer.” Interestingly, the Gwatkin-Hamilton proposals all favoured red and white which would eventually become Canada's colours. Hamilton, a staunch royalist who had proposed that Canada be made a kingdom, obviously understood that the maple leaf and crown would make a viable combination.

Todd recognized that the maple leaf was becoming increasingly popular and presented a beautiful simplicity, but he felt that the single leaf did not reveal enough and did not have sufficient history being “of very recent growth as a national symbol.”[4] To the maple leaf, he preferred symbols of the mother countries on the shield and proposed to Mulvey, as he had done to Hamilton, a red shield with a gold lion rampant in the centre surrounded by nine gold fleurs-de-lis, he added a helmet and crest in the form of a black moose, with golden horns and hooves, standing on the imperial crown. The supporters were, on the spectators left, a bison and, on the right, a polar bear, both in natural colours and adorned on the shoulder with a gold maple leaf (fig. 1).[5]

Fig. 1 Rough sketch of proposal for Canada’s arms by Herbert Todd

In retrospect, it is easy to see that the maple leaf was the rising star. For more than a century, it had been widely accepted by Anglophones and Francophones as an emblem of Canada and had also been adopted by the Canadian military. It was a single item with a huge baggage of symbolism and would retain this symbolism whether on a badge or on a shield. In fact, Todd’s attitude echoed that of Fiset who, after proposing a single maple leaf, began to have doubts that it may be too simple. Though Hamilton and Gwatkin had envisaged a single maple leaf, the hesitation to make a bold Canadian statement by introducing this single symbol lingered.

Todd had placed on the shield, the essential part of a coat of arms, the European lion and fleurs-de-lis, both of which had been stylized over many years. Around the shield, he had placed heavy-set Canadian animals drawn more or less as they exist in nature. Combining this naturalistic approach with stylized elements made for an incongruous composition. He had pointed out that animals make better supporters than humans, but stylizing a bison and polar bear to make them look alert and dignified is not the work of a “child drawing in the dark.” It requires skill, knowledge and willingness to consider many possibilities.[6] Moreover, simplicity in heraldry does not necessarily mean simplicity of execution; it also means limitation of the number of components. On the other hand, Todd’s design was an honest effort at reaching a balance between European and Canadian content. This approach was not different from that of the Antiquarian and Numismatic Society of Montreal (chapter 3, fig. 15). In fact, many of the proposals submitted aimed at reaching a balance between European and Canadian content.

A very prolific designer of proposed arms for Canada was Edgar J. Biggar, a professor of Spanish living in Toronto. Following the committee’s request for public proposals, Biggar bombarded the Department of the Secretary of State with his creations, which inevitably included Canadian symbols combined with European elements, such as a lion holding the Union Jack, fleurs-de-lis, and the crown. The presence of the crown is not surprising. From the 1870's, and without official sanction, the royal crown had usually topped the Dominion shield, those of the provinces and those of many freely adopted municipal coats of arms. Other suggestions, including those of George Herbert Todd, all contained a large number of Canadian symbols: maple leaves, beavers, moose, bears, bisons, Amerindians and voyageurs. References to European heritage and to the founding nations were also frequent.[7]

The 15 February 1919 Mail and Empire of Toronto carried a proposal from Biggar. A few years before the professor had taught geography at the Instituto Nacional de Panama and had been commissioned to paint the arms of the principal nations of the world on large metal shields. The 1868 arms of the original four provinces had been the target of adverse criticism by viewers as not being representative of the country as a whole. On the other hand, Biggar's judgement of the aggregate shield, meant to represent the entire country, echoed that of Morin (chapter 3): “Our present shield I maintain is but a complicated and confused mass of mythological and biological signs and symbols jumbled together in anything but an artistic design.” The professor vowed on his return to Canada to do something about this mess. He felt strongly that any design should contain the beaver and maple leaf, the two most popular emblems of the country.

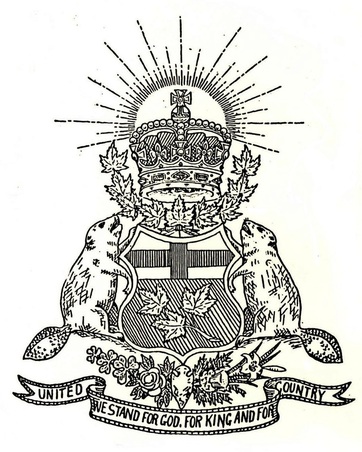

One of Biggar’s designs contained a sprig of three gold maple leaves on a green field combined with a gold chief (top part of the shield) with a red lion passant guardant (walking by, looking at the spectator). As supporters, he proposed an Amerindian and a moose, a completely asymmetric combination. On the shield, he placed a helmet facing forward with a crescent shaped slit, a vertical plaque, and mantling on top. The crest consisted of the imperial crown placed directly on the crest wreath in front of a gold sun representing prosperity. The motto was For God, for King and for Country. Below the shield appeared a beaver in front of a garland of roses, lilies, thistles and shamrocks representing the four founding nations (fig. 2). A second design was much the same except that it had a blue field with a silver chevron cluttered with nine green maple leaves. At the top, below the chief, were two gold fleurs-de-lis and in base a beaver proper (natural colours). The floral badges of the founding nations were retained under the shield, but motto had now become God Guard our Country (fig. 3).

Todd had placed on the shield, the essential part of a coat of arms, the European lion and fleurs-de-lis, both of which had been stylized over many years. Around the shield, he had placed heavy-set Canadian animals drawn more or less as they exist in nature. Combining this naturalistic approach with stylized elements made for an incongruous composition. He had pointed out that animals make better supporters than humans, but stylizing a bison and polar bear to make them look alert and dignified is not the work of a “child drawing in the dark.” It requires skill, knowledge and willingness to consider many possibilities.[6] Moreover, simplicity in heraldry does not necessarily mean simplicity of execution; it also means limitation of the number of components. On the other hand, Todd’s design was an honest effort at reaching a balance between European and Canadian content. This approach was not different from that of the Antiquarian and Numismatic Society of Montreal (chapter 3, fig. 15). In fact, many of the proposals submitted aimed at reaching a balance between European and Canadian content.

A very prolific designer of proposed arms for Canada was Edgar J. Biggar, a professor of Spanish living in Toronto. Following the committee’s request for public proposals, Biggar bombarded the Department of the Secretary of State with his creations, which inevitably included Canadian symbols combined with European elements, such as a lion holding the Union Jack, fleurs-de-lis, and the crown. The presence of the crown is not surprising. From the 1870's, and without official sanction, the royal crown had usually topped the Dominion shield, those of the provinces and those of many freely adopted municipal coats of arms. Other suggestions, including those of George Herbert Todd, all contained a large number of Canadian symbols: maple leaves, beavers, moose, bears, bisons, Amerindians and voyageurs. References to European heritage and to the founding nations were also frequent.[7]

The 15 February 1919 Mail and Empire of Toronto carried a proposal from Biggar. A few years before the professor had taught geography at the Instituto Nacional de Panama and had been commissioned to paint the arms of the principal nations of the world on large metal shields. The 1868 arms of the original four provinces had been the target of adverse criticism by viewers as not being representative of the country as a whole. On the other hand, Biggar's judgement of the aggregate shield, meant to represent the entire country, echoed that of Morin (chapter 3): “Our present shield I maintain is but a complicated and confused mass of mythological and biological signs and symbols jumbled together in anything but an artistic design.” The professor vowed on his return to Canada to do something about this mess. He felt strongly that any design should contain the beaver and maple leaf, the two most popular emblems of the country.

One of Biggar’s designs contained a sprig of three gold maple leaves on a green field combined with a gold chief (top part of the shield) with a red lion passant guardant (walking by, looking at the spectator). As supporters, he proposed an Amerindian and a moose, a completely asymmetric combination. On the shield, he placed a helmet facing forward with a crescent shaped slit, a vertical plaque, and mantling on top. The crest consisted of the imperial crown placed directly on the crest wreath in front of a gold sun representing prosperity. The motto was For God, for King and for Country. Below the shield appeared a beaver in front of a garland of roses, lilies, thistles and shamrocks representing the four founding nations (fig. 2). A second design was much the same except that it had a blue field with a silver chevron cluttered with nine green maple leaves. At the top, below the chief, were two gold fleurs-de-lis and in base a beaver proper (natural colours). The floral badges of the founding nations were retained under the shield, but motto had now become God Guard our Country (fig. 3).

Fig. 2 Design by Edgar J. Biggar in Mail and Empire, 15 February 1919. Pairing a human with an animal can be viewed as improper and usually presents problems of symmetry.

Fig. 3 Design by Edgar J. Biggar in Mail and Empire, 15 February 1919.

Fig. 4 Another design by Edgar J. Biggar. The shield is the arms of Ontario as granted in 1868 except that the leaves are described as being in “gold and autumnal tints” instead of just gold. Library and Archives Canada, RG 6, A1, vol. 210, file 1156, part 1.

The decorative wreath of roses, lilies, thistles and shamrocks (figs. 2-4) to represent the founding nations proposed by Biggar would be retained in the official grant to Canada, although a similar idea had already been expressed in 1892 (see chapter 3, fig. 8). The committee no doubt liked this idea which fitted so well with their own desire to honour the founders of the country. One recurrent theme in many proposed designs is that nine provinces must be represented somehow: nine maple leaves in chief by Morin (chapter 3, fig. 14), nine fleurs-de-lis by Todd (fig. 1) and nine maple leaves on a chevron by Biggar (fig. 3). Chadwick wrote the Mail and Empire condemning, in particular, Biggar’s use of the crown which he viewed as being “purely personal to the King” and not to be used without his authorization.[8]

From abroad came suggestions from John Alexander Stewart [9], “Convener of the Heraldic Committee” of the St. Andrew Society of Glasgow which had been in touch with the Antiquarian and Numismatic Society of Montreal. Some of his remarks were highly technical, even cryptic at times. He wanted Scotland to have a significant place in Canada’s arms and made a special effort to show how some Scottish symbols would be appropriate for Canada:

“Have you considered the tressure as a possible charge? It is the symbol of the Auld Alliance between France and Scotland, and if you put it round the ‘Lion of England’ (with or without Maple Leaves) you have a symbol of Anglo-Franco-Scottish (Canadian) Alliance and friendship. New France and New Scotland were the original provinces of Canada, and I suppose Mary Queen of France and of the Scots would be the Queen of New France also. The tressure would not be granted in ordinary cases, but it is already part of the arms of Nova Scotia, and if this were pointed out I have no doubt that His Majesty would grant it ...”[10]

Although an interesting idea, Stewart's Scottish tressure (double lines following the contour of the shield and decorated with fleurs-de-lis) was not retained by the Antiquarian and Numismatic Society. The society surely reasoned that, with a tressure and a lion, the proposed arms would resemble too closely those of Scotland. Still his remarks caused the society to modify its original suggestion and John Charles Alison Heriot, now Chairman of the Heraldic Committee of the Antiquarian and Numismatic Society, submitted a new design. The moose in the crest became a moose's head full face and the lion passant guardant on the shield was changed for a lion rampant (on hind feet). Beside the motto Dieu défend le roy, a second motto, “Onward Canada,” appeared above the crest in Scottish fashion, but Canadian in spirit. The supporters were replaced by a unicorn (originally a supporter of the arms of Scotland and eventually a supporter of the arms of the United Kingdom) and a moose. Two maple leaves accompanied the lion at the top of the shield and a fleur-de-lis in base. The Canadian content remained important and, no doubt, this design was approved by all members of the Society.[11] In fairness to Stewart, his suggestions helped to create a more dramatic design than the original proposal of the Antiquarian and Numismatic Society. A large moose head with huge antlers in the crest is more striking than a complete moose and a lion standing on the shield is more dramatic than a lion waking by. Moreover animals generally look better as supporters than humans.

Stewart’s influence did not end there. Encouraged by the acceptance that some of his suggestions had received, he wrote again to Heriot: “The English Heralds, who have no jurisdiction out of England, are fond of granting purely English coats. A Court of all the British Kings of Arms is really required to advise in matters of Imperial Heraldry, military flags, badges, etc.”[12]

Prompted by Stewart’s Scottish zeal, Herriot, another Scotsman, wrote to the federal committee requesting in strong terms that the Lyon King of Arms, Sir James Balfour Paul, and the “Ulster King of Arms of Ireland” should also be consulted. He went on to affirm “the government offices of Lyon and Ulster by law established possess a higher status than the fee-supported Heralds’ College of England” and “… we feel that it would be a very graceful and appropriate act on the part of your Committee to consult the Lyon King of Arms in this connection, particularly so as Scotland is the most ancient of the three Kingdoms, and as it is in virtue of his descent from her Royal Line that our present Sovereign, King George sits upon the British Throne”.[13] It does not seem that this letter was acknowledged by the committee. The suggestion to involve all the granting authorities in United Kingdom foreshadowed conflicting views and endless debate.

Besides Stewart, voices from abroad included the well-known author Rudyard Kipling and Sir George Perley, High Commissioner of Canada in London. Both felt that the participation of the Dominions in the war should be recognized by an augmentation of honour. They had discussed the matter at the Ritz Hotel (London) and Perley had made their views known to Mulvey. These augmentations, they suggested, would “be placed on a Shield crowned by the Imperial crown in the centre of the present arms” and the choice of augmentations would be made by an “Inter-Dominion Commission of experts.”[14] The suggestion was analysed, possibly by Hamilton, and judged to be a little premature where Canada was concerned. A memorandum on the subject noted that such augmentations were special marks of favour from the sovereign and were granted by Royal warrant and recorded at the College of Arms. It further noted: “Technically speaking, a gift of arms by the sovereign where none previously existed is not an augmentation, though one is naturally inclined to include such grants in the category.”[15] The Kipling-Perley proposal was of course an effort to create greater cohesion between members of the empire.

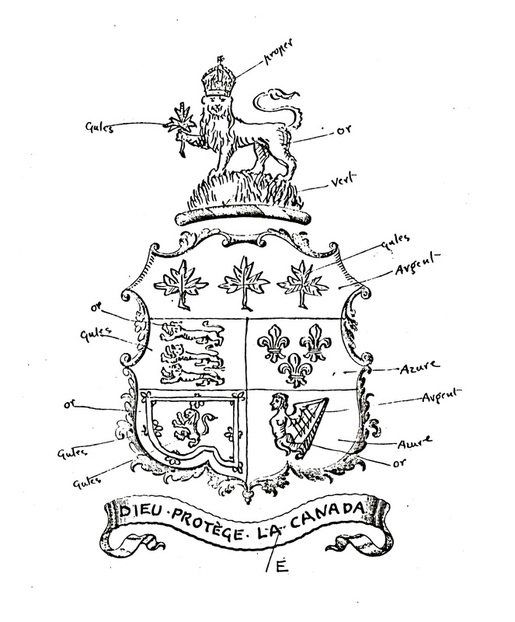

Unexpectedly, another letter came from abroad. Ambrose Lee, York Herald, was responding to earlier correspondence with Pope. York was in serious disarray. His artist had died early in 1916 and any sketch which he might have done for Canadian arms had disappeared. Based on earlier correspondence with Pope, Lee had come up with most of the elements which would eventually compose the official arms of Canada. Included were the arms of the four founding nations (arranged differently than in the present arms) and the three separate red maple leaves side by side, and in chief ( upper part) rather than in base. The crest was the same as in the present arms except that the lion was standing on a green mound (fig. 5). Lee further proposed the unicorn as one supporter with possibly an angel taken from the royal arms of France (a surprising combination as Chadwick will point out) and suggested that each hold banners one of which could be the Union Jack. The suggested motto was Dieu protège la (sic) Canada, a variant on Dieu protège le roy proposed by Chadwick and the Antiquarian and Numismatic Society of Montreal. Lee's suggestion was open to discussion and his approach was flexible and friendly: “It would help us very much if suggestions could be put forward from your side; it is so difficult for us here to judge the trend of taste and opinion in Canada on such matters.”[16]

From abroad came suggestions from John Alexander Stewart [9], “Convener of the Heraldic Committee” of the St. Andrew Society of Glasgow which had been in touch with the Antiquarian and Numismatic Society of Montreal. Some of his remarks were highly technical, even cryptic at times. He wanted Scotland to have a significant place in Canada’s arms and made a special effort to show how some Scottish symbols would be appropriate for Canada:

“Have you considered the tressure as a possible charge? It is the symbol of the Auld Alliance between France and Scotland, and if you put it round the ‘Lion of England’ (with or without Maple Leaves) you have a symbol of Anglo-Franco-Scottish (Canadian) Alliance and friendship. New France and New Scotland were the original provinces of Canada, and I suppose Mary Queen of France and of the Scots would be the Queen of New France also. The tressure would not be granted in ordinary cases, but it is already part of the arms of Nova Scotia, and if this were pointed out I have no doubt that His Majesty would grant it ...”[10]

Although an interesting idea, Stewart's Scottish tressure (double lines following the contour of the shield and decorated with fleurs-de-lis) was not retained by the Antiquarian and Numismatic Society. The society surely reasoned that, with a tressure and a lion, the proposed arms would resemble too closely those of Scotland. Still his remarks caused the society to modify its original suggestion and John Charles Alison Heriot, now Chairman of the Heraldic Committee of the Antiquarian and Numismatic Society, submitted a new design. The moose in the crest became a moose's head full face and the lion passant guardant on the shield was changed for a lion rampant (on hind feet). Beside the motto Dieu défend le roy, a second motto, “Onward Canada,” appeared above the crest in Scottish fashion, but Canadian in spirit. The supporters were replaced by a unicorn (originally a supporter of the arms of Scotland and eventually a supporter of the arms of the United Kingdom) and a moose. Two maple leaves accompanied the lion at the top of the shield and a fleur-de-lis in base. The Canadian content remained important and, no doubt, this design was approved by all members of the Society.[11] In fairness to Stewart, his suggestions helped to create a more dramatic design than the original proposal of the Antiquarian and Numismatic Society. A large moose head with huge antlers in the crest is more striking than a complete moose and a lion standing on the shield is more dramatic than a lion waking by. Moreover animals generally look better as supporters than humans.

Stewart’s influence did not end there. Encouraged by the acceptance that some of his suggestions had received, he wrote again to Heriot: “The English Heralds, who have no jurisdiction out of England, are fond of granting purely English coats. A Court of all the British Kings of Arms is really required to advise in matters of Imperial Heraldry, military flags, badges, etc.”[12]

Prompted by Stewart’s Scottish zeal, Herriot, another Scotsman, wrote to the federal committee requesting in strong terms that the Lyon King of Arms, Sir James Balfour Paul, and the “Ulster King of Arms of Ireland” should also be consulted. He went on to affirm “the government offices of Lyon and Ulster by law established possess a higher status than the fee-supported Heralds’ College of England” and “… we feel that it would be a very graceful and appropriate act on the part of your Committee to consult the Lyon King of Arms in this connection, particularly so as Scotland is the most ancient of the three Kingdoms, and as it is in virtue of his descent from her Royal Line that our present Sovereign, King George sits upon the British Throne”.[13] It does not seem that this letter was acknowledged by the committee. The suggestion to involve all the granting authorities in United Kingdom foreshadowed conflicting views and endless debate.

Besides Stewart, voices from abroad included the well-known author Rudyard Kipling and Sir George Perley, High Commissioner of Canada in London. Both felt that the participation of the Dominions in the war should be recognized by an augmentation of honour. They had discussed the matter at the Ritz Hotel (London) and Perley had made their views known to Mulvey. These augmentations, they suggested, would “be placed on a Shield crowned by the Imperial crown in the centre of the present arms” and the choice of augmentations would be made by an “Inter-Dominion Commission of experts.”[14] The suggestion was analysed, possibly by Hamilton, and judged to be a little premature where Canada was concerned. A memorandum on the subject noted that such augmentations were special marks of favour from the sovereign and were granted by Royal warrant and recorded at the College of Arms. It further noted: “Technically speaking, a gift of arms by the sovereign where none previously existed is not an augmentation, though one is naturally inclined to include such grants in the category.”[15] The Kipling-Perley proposal was of course an effort to create greater cohesion between members of the empire.

Unexpectedly, another letter came from abroad. Ambrose Lee, York Herald, was responding to earlier correspondence with Pope. York was in serious disarray. His artist had died early in 1916 and any sketch which he might have done for Canadian arms had disappeared. Based on earlier correspondence with Pope, Lee had come up with most of the elements which would eventually compose the official arms of Canada. Included were the arms of the four founding nations (arranged differently than in the present arms) and the three separate red maple leaves side by side, and in chief ( upper part) rather than in base. The crest was the same as in the present arms except that the lion was standing on a green mound (fig. 5). Lee further proposed the unicorn as one supporter with possibly an angel taken from the royal arms of France (a surprising combination as Chadwick will point out) and suggested that each hold banners one of which could be the Union Jack. The suggested motto was Dieu protège la (sic) Canada, a variant on Dieu protège le roy proposed by Chadwick and the Antiquarian and Numismatic Society of Montreal. Lee's suggestion was open to discussion and his approach was flexible and friendly: “It would help us very much if suggestions could be put forward from your side; it is so difficult for us here to judge the trend of taste and opinion in Canada on such matters.”[16]

Fig. 5 Lee’s proposal for Canada, June 1919. Library and Archives Canada, RG 6, A1, vol. 210, file 1156, part 1.

Lee’s design respected Pope's wish to emphasize imperial ties and the monarchy and was well received by the committee to which it provided focus. Nevertheless, Doughty still favoured the lion and unicorn as supporters and thought these might prove acceptable if the lion was on the right and the unicorn on the left, reversing their position with respect to the royal arms. Otherwise, he proposed coupling an Amerindian with an angel.[17] Gwatkin, for his part, favoured a sprig of maple as in the arms of Ontario and Quebec rather than the three separate leaves (a proposal retained). He remarked that if “so sensitive” was “the Protestant conscience,” the angel could be replaced by an early settler holding an axe or an eastern Amerindian holding a bow. Gwatkin's supporters were inspired by a fanciful drawing in which Todd had added a settler and an Amerindian as supporters of the province of Quebec (fig. 6).[18] Latter Gwatkin became concerned that Dieu protège le Canada might be objected to, being French. He proposed instead the motto of Louis XIV, Nec pluribus impar (Not equalled by many) “as an answer to our next door neighbour's crow: E pluribus unum” (One out of many).[19] Gwatkin was an interesting member of the committee who sought to promote Canadian content, but to oppose Louis XIV’s pompous motto to that of the United States, a mere statement of fact, was not particularly inspired.

Fig. 6 Herbert Todd’s proposal of a crest and supporters for the province of Quebec, the supporters being: Dexter an eastern Indian holding in his outer hand a bow; sinister an early settler holding in his outer hand an axe, all proper. From his Armory and Lineages of Canada (Yonkers, N.Y., 1919), plates after page 122.

The committee often met in impromptu fashion, often in Mulvey's office, and rarely recorded its minutes. Following the July 15 meeting, a lengthy memorandum was prepared clearly outlining where the committee was heading. Three designs were being proposed. The first one was, with one minor change, what Lee had proposed (fig. 5), namely: 1) England, 2) France, 3) Scotland, 4) Ireland and a white chief with three separate red maple leaves. The crest was that of the present arms, except that the green mound in Lee’s proposal was removed. The motto remained Dieu protège le Canada and the supporters were also inspired by Lee: on the left, the unicorn holding the Union Jack; on the right, an angel holding a blue banner with three gold fleurs-de-lis and a red maple leaf in the left hand.

The second design was the same as the first except that the three maple leaves in chief were now joined on one stem as Gwatkin had proposed and the right supporter, instead of an angel, was a coureur de bois holding in the left hand a flint-lock riffle. The motto was that of Louis XIV, Nec pluribus impar. In the third design, the banners were removed and the supporter on the right was an Indian with a feather head-dress and holding in the left hand a bow and arrow. The motto remained Dieu protège le Canada.

The memorandum further explained that the objectives of the committee were: “to secure a satisfactory symbol for Canada, which will embody personal and national loyalty and pride.” This would be achieved by combining into one design “a reference to the past, a suggestion of our present status as a daughter nation, and a vision of the hopes of our future.” The link to the past was achieved by including European heritage. The present status “as a daughter nation” was expressed by the emblems of the founding nations, the many components derived from the king’s arms and the red maple leaves which had become a symbol of courage during the war: “… a red leaf on a service flag denoted a Canadian who had laid down his life for his country.”[20] The white background represented Canadian winters in which some authors saw an allusion to “Our Lady of the Snows.” The memorandum also contained a number of aesthetic considerations and justified the exclusion of more traditional Canadian emblems like the beaver by the fact that they had not yet been properly stylised as had been the lions of England over the years. It rejected as well nine leaves as being too small for “distinctive treatment” and a single leaf as being “… too large, and would tempt artists to make a picture of it, instead of conventionalizing it, as is proper in heraldry.” It further explained that the crest derived from two crests, that of Scotland and that of England. The position of the lion was patterned on the crest of England and the maple leaf in its paw mimicked the Scottish crest in which a lion holds a dagger. The memorandum also upheld that the inclusion of royal symbols was justified because, although the royal arms are “the personal property of the King,” they are his “by virtue of his position as sovereign, and not in his private capacity.”[21] How the “vision of the hopes of the future” was to be reflected was not explained, although it was clear that this role would be under the Crown and within the empire.[22]

In the meantime, Chadwick worried that the committee would bungle things without the guidance of a heraldic expert. He wrote Mulvey on December 4 recommending that, if the committee did not go to the College of Arms by measure of economy, it should ask the governor general to approve the arms. He felt that the governor general had the required powers to grant arms if he thought it appropriate to do so.[23] Mulvey informed Chadwick that the committee was in correspondence with the College of arms and that the present delays were caused by the college not responding.[24]

During December and January, Chadwick wrote a series of letters to Mulvey offering words of caution. His main source of information was rumours so that many of his remarks were off-base. Dieu protège le Canada, in his mind, had republican overtones whereas his own earlier suggestion, Dieu protège le roy was clearly monarchical. The angel too had to be removed because its iconography had evolved into that of a heathen goddess,[25] and combining a unicorn with an angel was disturbing: “… surely any sensible person would not seriously propose to pair an animal with a human or human like form.” He further cautioned that the king's permission was required for the use of a royal crest. He pointed out again that Amerindians supporters were highly appropriate having been granted in 1664 to the French East India Company which operated in Canada. Because York Herald had been a source of delay, he recommended abandoning him in favour of Charles H. Athill, Richmond Herald, with whom he had corresponded, but by then Athill had become Clarenceux King of Arms.[26] Some of Chadwick’s views, such as the impropriety of combining an angel with a beast, understandably made an impression on the committee, while other suggestions were ignored.

On 20 January 1920, Lee finally responded from a nursing home where he was confined with heart problems. A colleague had been asked to deal with the Canadian grant, but had done nothing. Since his health was improving, he was anxious to get on with the task. He already had negotiated the arms of nineteen British colonies including South Africa, New Zealand and Australia and was looking forward to his twentieth grant. He was hoping to send shortly “an official sketch embodying the closest approximation to the Royal achievement which may be practicable.”[27]

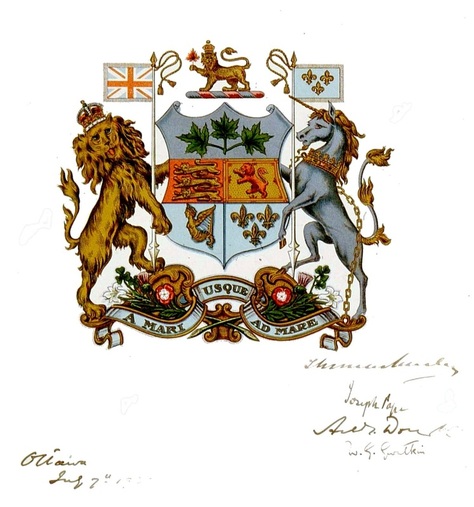

In the meantime, the design favoured by the committee was obviously leaked to the press. On January 20, Doughy asked Alexander Scott Carter to reproduce for him a line drawing of the proposed arms which had appeared in the Toronto Saturday Night. The drawing produced by Carter (fig. 7) had the same components as the arms eventually adopted by the committee and printed for distribution (fig. 8), the only differences being that Carter's rendering placed the lion on a mound and was far superior heraldic art than the latter, even if he made a small mistake in the Latin a mare instead of a mari.[28]

The second design was the same as the first except that the three maple leaves in chief were now joined on one stem as Gwatkin had proposed and the right supporter, instead of an angel, was a coureur de bois holding in the left hand a flint-lock riffle. The motto was that of Louis XIV, Nec pluribus impar. In the third design, the banners were removed and the supporter on the right was an Indian with a feather head-dress and holding in the left hand a bow and arrow. The motto remained Dieu protège le Canada.

The memorandum further explained that the objectives of the committee were: “to secure a satisfactory symbol for Canada, which will embody personal and national loyalty and pride.” This would be achieved by combining into one design “a reference to the past, a suggestion of our present status as a daughter nation, and a vision of the hopes of our future.” The link to the past was achieved by including European heritage. The present status “as a daughter nation” was expressed by the emblems of the founding nations, the many components derived from the king’s arms and the red maple leaves which had become a symbol of courage during the war: “… a red leaf on a service flag denoted a Canadian who had laid down his life for his country.”[20] The white background represented Canadian winters in which some authors saw an allusion to “Our Lady of the Snows.” The memorandum also contained a number of aesthetic considerations and justified the exclusion of more traditional Canadian emblems like the beaver by the fact that they had not yet been properly stylised as had been the lions of England over the years. It rejected as well nine leaves as being too small for “distinctive treatment” and a single leaf as being “… too large, and would tempt artists to make a picture of it, instead of conventionalizing it, as is proper in heraldry.” It further explained that the crest derived from two crests, that of Scotland and that of England. The position of the lion was patterned on the crest of England and the maple leaf in its paw mimicked the Scottish crest in which a lion holds a dagger. The memorandum also upheld that the inclusion of royal symbols was justified because, although the royal arms are “the personal property of the King,” they are his “by virtue of his position as sovereign, and not in his private capacity.”[21] How the “vision of the hopes of the future” was to be reflected was not explained, although it was clear that this role would be under the Crown and within the empire.[22]

In the meantime, Chadwick worried that the committee would bungle things without the guidance of a heraldic expert. He wrote Mulvey on December 4 recommending that, if the committee did not go to the College of Arms by measure of economy, it should ask the governor general to approve the arms. He felt that the governor general had the required powers to grant arms if he thought it appropriate to do so.[23] Mulvey informed Chadwick that the committee was in correspondence with the College of arms and that the present delays were caused by the college not responding.[24]

During December and January, Chadwick wrote a series of letters to Mulvey offering words of caution. His main source of information was rumours so that many of his remarks were off-base. Dieu protège le Canada, in his mind, had republican overtones whereas his own earlier suggestion, Dieu protège le roy was clearly monarchical. The angel too had to be removed because its iconography had evolved into that of a heathen goddess,[25] and combining a unicorn with an angel was disturbing: “… surely any sensible person would not seriously propose to pair an animal with a human or human like form.” He further cautioned that the king's permission was required for the use of a royal crest. He pointed out again that Amerindians supporters were highly appropriate having been granted in 1664 to the French East India Company which operated in Canada. Because York Herald had been a source of delay, he recommended abandoning him in favour of Charles H. Athill, Richmond Herald, with whom he had corresponded, but by then Athill had become Clarenceux King of Arms.[26] Some of Chadwick’s views, such as the impropriety of combining an angel with a beast, understandably made an impression on the committee, while other suggestions were ignored.

On 20 January 1920, Lee finally responded from a nursing home where he was confined with heart problems. A colleague had been asked to deal with the Canadian grant, but had done nothing. Since his health was improving, he was anxious to get on with the task. He already had negotiated the arms of nineteen British colonies including South Africa, New Zealand and Australia and was looking forward to his twentieth grant. He was hoping to send shortly “an official sketch embodying the closest approximation to the Royal achievement which may be practicable.”[27]

In the meantime, the design favoured by the committee was obviously leaked to the press. On January 20, Doughy asked Alexander Scott Carter to reproduce for him a line drawing of the proposed arms which had appeared in the Toronto Saturday Night. The drawing produced by Carter (fig. 7) had the same components as the arms eventually adopted by the committee and printed for distribution (fig. 8), the only differences being that Carter's rendering placed the lion on a mound and was far superior heraldic art than the latter, even if he made a small mistake in the Latin a mare instead of a mari.[28]

Fig. 7 Drawing of proposed arms for Canada by A. S. Carter, 1920. The motto should read: A mari usque ad mare. LAC photo C-133326.

In a subsequent letter dated March 22, we learn that the colleague who had failed Lee was no other than Sir Henry Farnham Burke, Garter King of Arms. In recent discussions, York had learned that Garter was strongly opposed to royal arms for Canada and was not prepared to propose such a design for His Majesty's approval. Garter was of the opinion that Canada's arms should include royal badges such as the rose, the shamrock, the thistle, the fleur-de-lis to which the maple leaf could be added “with perhaps the Imperial Arms as a sort of centre.” Suitable supporters would be Amerindians or indigenous animals. In an accompanying drawing, the shield displayed the royal crown between a maple branch and a rose branch their stems tied with a ribbon, within a tressure (an inner band shaped as the contours of the shield) decorated with fleurs-de-lis alternately pointing inwards and outwards. The crest was the royal crown on a rose between a maple branch on the left and a branch with fleurs-de-lis on the right.[29]

Pope judged Lee's response to be “unsatisfactory” and proposed holding a meeting.[30] The reasons for Garters opposition had not been spelt out and the dainty looking arms being proposed did not reflect the rugged strength of Canada's vast expanses and huge potential. Above all, Pope must have felt that Canada was being treated like a colony and Canadians as being less than British citizens.

Gwatkin seized upon this occasion to promote Canadian content. He proposed to the committee a white shield with nine red maple leaves (rejected earlier by the committee) placed three, three, two and one within a red tressure flory counter-flory (as in the arms of Scotland), as crest a beaver proper (rejected earlier by the committee) surmounted by the Imperial crown, as motto A mari usque ad mare, and as supporters two caribous proper, one holding the Union Flag, the other, the banner of France.[31] A few days later, he had changed his mind and wanted the nine leaves to become three sprigs of three leaves each.[32] However, just prior to the meeting, he received from Mulvey a letter exposing Pope's view that they should go on with the original proposition with only minor changes, such as how the supporters could be differentiated from those of the United Kingdom.

As a result of Garter's opposition, the committee was forced to express more clearly its own views. They at first discussed placing a St. George cross in chief, but the idea was abandoned.[33] When the committee met on April 13, it clearly stated that it was seeking a version of the royal arms such as existed for England and Scotland and that these “should be unmistakeably an expression of the relation of the Sovereign to his Canadian people”. It also decided “with profound respect” to present their design to His Majesty.

“The Committee take it that the proposed ‘Arms of Canada’ in any event will be His Majesty's Arms as Sovereign of Canada, and that, once they are adopted, it will be as anomalous to display in Canada the Royal Arms as used in England as it would be to use those Arms in Scotland, in lieu of the arrangement (with different crest and mottoes and altered arrangements of quarterings and supporters) which prevails in that Kingdom.”

They wanted, they said, to create an impression of “continuity and development in status” and a design in the format of royal arms: “On the other hand, if the familiar Royal Arms were replaced by a device wholly different, and clearly inspired by local sentiment and traditions, almost to the exclusion of recognition of the past, the question arises of the nature of the real impression which would be created.”

The hopes for the future were now clearly spelt out as being the continuation of monarchical government. They realized that the arms adopted would either mean greater Canadian nationalism or stronger unity of the empire and, of the two, they preferred arms which emphasized “continuity and union.” It was now clear in the committee's mind that Canada's arms should be His Majesty's royal arms for Canada based on those of the United Kingdom, with limited Canadian content. The committee members unequivocally stated “that their task above all” was “political.” This went a long way towards explaining the exclusion of heraldists like Chadwick from the committee.[34]

The committee’s strong statement was in harmony with Pope’s desire for close ties with the Crown and the recognition that Canadians are British citizens on the same footing as those of England. In an embryonic stage, we find there the ideas expressed by the Balfour Declaration which pronounced members of the empire to be equal under the Crown, a statement which became law by the Statute of Westminster in 1931. In fact, it was not that far away from the notion of a King or Queen of Canada, which would become a reality in 1953.

Certainly there was no desire on the part of Pope to weaken the empire in favour of the Dominions. A draft booklet prepared in 1921 to describe Canada’s arms once they were granted stated that the royal arms took one form for England, another for Scotland and yet another for Canada. Though it was expressed in a vague circuitous way, the statement implied that Canada was equal to England and Scotland with respect to the Crown. In other words, the three countries each possessed an armorial instrument which, while respecting their distinctiveness, expressed an identical relationship with respect to the sovereign. This was precisely what the other members of the committee wanted, but Pope took exception to: “... the Dominion of Canada being on equality of status with the ancient Kingdom of Scotland. I do not wish to be associated with any such statement and I would suggest that the simplest way would be that my name might be left out.” Mulvey replied that there was no personal association as no one would be signing.[35] Pope’s views regarding the relationship of Dominions to the empire were becoming archaic. He was likely aware of that since he did not ask Mulvey to change his statement, only not to associate his name with it.

When presented in the form of a rough sketch, the arms adopted at the April 13 meeting were judged acceptable. Gwatkin merely stated: “Instead of having rose and thistle on the dexter, with shamrock and lily on the sinister side, I would have rose, thistle, shamrock and lily on both sides.”[36] Pope preferred the floral arrangement as originally presented, but could accept Gwatkin's suggestion if it did not create a crowded appearance. The idea of placing the emblems symmetrically on both sides prevailed and became part of the committee's design. Another suggestion from Pope was listened to but clearly revealed his ignorance of heraldic aesthetics: “I trust that on consideration, we may come round to the green maple leaves. The more I consider the matter, the more I am inclined to the opinion that it is preferable that the leaves should speak of growth and life rather than decay and approaching dissolution, which the sere [withered] and yellow, or even the red leaf, to my mind symbolizes.”[37]

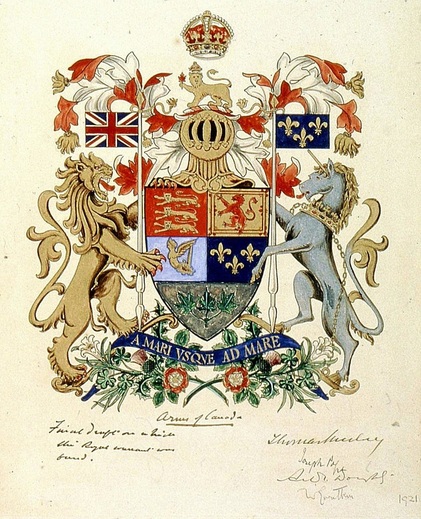

At the end of May, a drawing of the proposed arms was prepared by Fortunat Champagne, an illustrator and calligrapher who worked for the Secretary of State of Canada. [38] The drawing was printed at the end of June as a means of making the design known to those concerned.[39] The arms were close to the present ones except that the maple leaves were green and were at the top of the shield rather than in base as they are today. There were neither helmet nor mantling, the crown above the present arms was missing and the lion wore the royal crown and looked at the spectator (fig. 8).

Pope judged Lee's response to be “unsatisfactory” and proposed holding a meeting.[30] The reasons for Garters opposition had not been spelt out and the dainty looking arms being proposed did not reflect the rugged strength of Canada's vast expanses and huge potential. Above all, Pope must have felt that Canada was being treated like a colony and Canadians as being less than British citizens.

Gwatkin seized upon this occasion to promote Canadian content. He proposed to the committee a white shield with nine red maple leaves (rejected earlier by the committee) placed three, three, two and one within a red tressure flory counter-flory (as in the arms of Scotland), as crest a beaver proper (rejected earlier by the committee) surmounted by the Imperial crown, as motto A mari usque ad mare, and as supporters two caribous proper, one holding the Union Flag, the other, the banner of France.[31] A few days later, he had changed his mind and wanted the nine leaves to become three sprigs of three leaves each.[32] However, just prior to the meeting, he received from Mulvey a letter exposing Pope's view that they should go on with the original proposition with only minor changes, such as how the supporters could be differentiated from those of the United Kingdom.

As a result of Garter's opposition, the committee was forced to express more clearly its own views. They at first discussed placing a St. George cross in chief, but the idea was abandoned.[33] When the committee met on April 13, it clearly stated that it was seeking a version of the royal arms such as existed for England and Scotland and that these “should be unmistakeably an expression of the relation of the Sovereign to his Canadian people”. It also decided “with profound respect” to present their design to His Majesty.

“The Committee take it that the proposed ‘Arms of Canada’ in any event will be His Majesty's Arms as Sovereign of Canada, and that, once they are adopted, it will be as anomalous to display in Canada the Royal Arms as used in England as it would be to use those Arms in Scotland, in lieu of the arrangement (with different crest and mottoes and altered arrangements of quarterings and supporters) which prevails in that Kingdom.”

They wanted, they said, to create an impression of “continuity and development in status” and a design in the format of royal arms: “On the other hand, if the familiar Royal Arms were replaced by a device wholly different, and clearly inspired by local sentiment and traditions, almost to the exclusion of recognition of the past, the question arises of the nature of the real impression which would be created.”

The hopes for the future were now clearly spelt out as being the continuation of monarchical government. They realized that the arms adopted would either mean greater Canadian nationalism or stronger unity of the empire and, of the two, they preferred arms which emphasized “continuity and union.” It was now clear in the committee's mind that Canada's arms should be His Majesty's royal arms for Canada based on those of the United Kingdom, with limited Canadian content. The committee members unequivocally stated “that their task above all” was “political.” This went a long way towards explaining the exclusion of heraldists like Chadwick from the committee.[34]

The committee’s strong statement was in harmony with Pope’s desire for close ties with the Crown and the recognition that Canadians are British citizens on the same footing as those of England. In an embryonic stage, we find there the ideas expressed by the Balfour Declaration which pronounced members of the empire to be equal under the Crown, a statement which became law by the Statute of Westminster in 1931. In fact, it was not that far away from the notion of a King or Queen of Canada, which would become a reality in 1953.

Certainly there was no desire on the part of Pope to weaken the empire in favour of the Dominions. A draft booklet prepared in 1921 to describe Canada’s arms once they were granted stated that the royal arms took one form for England, another for Scotland and yet another for Canada. Though it was expressed in a vague circuitous way, the statement implied that Canada was equal to England and Scotland with respect to the Crown. In other words, the three countries each possessed an armorial instrument which, while respecting their distinctiveness, expressed an identical relationship with respect to the sovereign. This was precisely what the other members of the committee wanted, but Pope took exception to: “... the Dominion of Canada being on equality of status with the ancient Kingdom of Scotland. I do not wish to be associated with any such statement and I would suggest that the simplest way would be that my name might be left out.” Mulvey replied that there was no personal association as no one would be signing.[35] Pope’s views regarding the relationship of Dominions to the empire were becoming archaic. He was likely aware of that since he did not ask Mulvey to change his statement, only not to associate his name with it.

When presented in the form of a rough sketch, the arms adopted at the April 13 meeting were judged acceptable. Gwatkin merely stated: “Instead of having rose and thistle on the dexter, with shamrock and lily on the sinister side, I would have rose, thistle, shamrock and lily on both sides.”[36] Pope preferred the floral arrangement as originally presented, but could accept Gwatkin's suggestion if it did not create a crowded appearance. The idea of placing the emblems symmetrically on both sides prevailed and became part of the committee's design. Another suggestion from Pope was listened to but clearly revealed his ignorance of heraldic aesthetics: “I trust that on consideration, we may come round to the green maple leaves. The more I consider the matter, the more I am inclined to the opinion that it is preferable that the leaves should speak of growth and life rather than decay and approaching dissolution, which the sere [withered] and yellow, or even the red leaf, to my mind symbolizes.”[37]

At the end of May, a drawing of the proposed arms was prepared by Fortunat Champagne, an illustrator and calligrapher who worked for the Secretary of State of Canada. [38] The drawing was printed at the end of June as a means of making the design known to those concerned.[39] The arms were close to the present ones except that the maple leaves were green and were at the top of the shield rather than in base as they are today. There were neither helmet nor mantling, the crown above the present arms was missing and the lion wore the royal crown and looked at the spectator (fig. 8).

Fig. 8 Print of the proposed arms for Canada signed by members of Arms Committee, Ottawa, July 7th 1920, from a drawing by Fortunat Champagne. LAC neg. C-133325.

A report of the committee describing the arms and how they had come about was sent via the Privy Council for approval by the Governor General.[40] The approved report went to His Majesty with a request that he direct the College of Arms to grant the arms as described.[41]

One usual silly comment, at least from a heraldist's point of view, was made by P. D. Robertson, minister of labour, regarding the lion's tongue.[42] To his credit, however, he did admit that he could be wrong: “I would respectfully suggest that, inasmuch as the lion represents strength and dignity and as its head is adorned by the British Crown, it would be more appropriate if the lion's tongue were not exposed. There may, however, be some good reason why this change should not be made.”[43]

More pertinent to the debate were Chadwick's comments when he was confidentially sent a copy of the printed arms by Mulvey. It came with the warning that the design should not be made public before being officially confirmed as “it might be condemned through the spreading of misrepresentations by some half-baked reporter.”[44] Chadwick agreed with the need for confidentiality; he had himself seen too many suggestions “made in ignorance or bad taste.” Apart from his usual fear that the committee might come up with a faulty blazon (heraldic description), he stressed that the complex shield, which he described as Hanoverian, was no longer favoured by heraldic artists of high repute. They now preferred, he said, the shield shaped like a clothes iron which he called the “Chivalric English Shield.” He further pointed out that the coat of arms was incomplete without helmet and mantling. He thought the arms of the founding nations were appropriate provided they were approved. Otherwise, in his view, appropriating something which belonged to the sovereign was “high treason.” He warned that the acceptance of the maple leaf above the royal quarters was not likely to meet the approval of the king or of the heralds and sent a sketch proposing that the leaves should appear below England and Scotland, but above France and Ireland. This proposal, he maintained, had the further advantage that it made the heraldic description easier.[45]

Mulvey responded that the artist had made the shield as found in the royal arms of Victoria, but that they did not feel bound by that particular shape. He stated as well that the committee had hesitations about the helmet and mantling as these were not personal arms, which of course made little heraldic sense. He further pointed out that the entire coat of arms would be submitted for the approval of the king and thus the problem of royal approval would be overcome. The committee's hesitation with the helmet and mantling stemmed from a statement made by a herald.[46] In a letter dated July 25, 1907 Charles H. Athill, Richmond Herald, had stated to the Honourable J.P. Whitney, Prime Minister of Ontario, that “in the event of a Crest being granted to the Province no helmet would according to precedent be assigned.”[47] What precedent Richmond was referring to is not clear. A 1729 depiction of the arms granted to Nova Scotia c. 1625 does contain a helmet, [48] and the letters patent of King Charles I granting arms to Newfoundland in 1637 clearly specify one. In 1907, the other provinces did not have crests and therefore no helmet was needed. When the arms of Ontario were augmented with a crest in 1909, no helmet or mantling was specified in the royal warrant and none were included in the accompanying rendering.[49]

The question of the Ontario arms without helmet had been a sore point with Chadwick for some time. He strongly felt that a crest “without the helmet is like an armed man going into action with his scabbard without his sword, or it is like a man having a saddle and bridle but no horse to put them on!” He called such arms an “abbreviated achievement.” When he protested to the College of Arms, he was told that the helmet was implied in the Ontario grant and would not necessarily have been spelt out in the letters patent.[50] In other words, while the helmet and mantling were omitted in the blazon, they should have appeared in the drawing which serves as a guide as to how the arms should look.

When Pope saw Chadwick's comments, he concurred with Mulvey that they should be discussed with York Herald by Gwatkin who was sailing for England on July 24. Not being a heraldic expert, Pope was “prepared for any small changes of this nature which do not touch any question of principle.”[51] In the meantime, however, Mulvey had decided that Gwatkin should go directly to the official in authority, Sir Alfred Scott-Gatty whom he believed to still be Garter King of Arms. Moreover, the letter of introduction to Garter did not reveal that a submission had been made to the king. It stated: “These Arms are, in the near future, to be submitted to the College of Heralds to be recorded if same are duly approved. They may be further considered and reported upon by the College of Heralds, and for that reason it may be necessary for further representations to be made to you on the subject.”[52]

In other words, Gwatkin was there to iron out any further difficulties before the College was directed by the king to record the arms he approved. The manoeuvre was a strange one to say the least. Why should the advice of Garter be sought at this point since it was presumed that whatever he may have to say would be overridden once the king had approved the Canadian design? If it was thought that he could offer useful advice, he should have been consulted during the design process. Moreover, Ambrose Lee, York Herald, had already informed the committee that Garter was opposed to royal arms for Canada.

Gwatkin was not convinced of the necessity of a version of the royal arms, and he had many times made known his preference for predominantly Canadian symbols. It seems that he was chosen as armorial ambassador solely because he happened to be going to England on military business. If the intention was to convince Garter of the Canadian position, Pope would have no doubt been the more forceful man for the mission. However, he was not going to England; he was about to leave for holidays at Little Metis Beach on the south shore of the St. Lawrence. Neither Mulvey nor Gwatkin seemed to have taken time to think things out. In Pope's mind, Gwatkin was to go to York Herald to discuss the matters raised by Chadwick. Should the arms include a helmet? What was the best type of shield? The situation was further confused by the fact that Scott-Gatty, to whom Mulvey's letter of introduction was addressed, had been dead for over a year and a half and had been replaced by Sir Henry Farnham Burke whose opposition to royal arms for Canada, York Herald had made known to the committee.

When Pope learned that Gwatkin was approaching Garter directly, he was upset. He was also annoyed that Gwatkin had discussed the question of arms with the king's private secretary, Baron Arthur John Bigge Stamfordham, as well as with the colonial secretary, Viscount Alfred Milner. He wrote Mulvey:

“I am afraid Gwatkin is going the wrong way about it. There is no use in approaching Garter directly. He will not allow us the lion and the unicorn. The York Herald in his letter to me distinctly says as much. Our only chance of success lies in indirect methods. The G.G. has written Lord Edmund Talbot, the Acting Earl Marshall, privately. The Duke of Connaught [former governor general of Canada] has also been written to. I never counted on Lord Stamfordham in this matter for anything. It is not to be expected that the King's Private Secretary would concern himself with such a question as Arms for a distant Dominion, or Lord Milner either. I never was sanguine from being able to secure the Arms so closely approximating to the Royal Arms, but we must pull every wire and even should everything fail, I am proud to have my name associated with a design at once so appropriate striking and complete as is our recommendation. I am returning to Ottawa in a few days when Doughty, you and I might meet and have a talk.”[53]

On August 30, Gwatkin met with Garter: “This morning I had a long talk with Garter, who discountenances the use of the King's personal Arms. I asked him to suggest something better; & I left him in the agony, so to speak, of composition.”[54] Two days later, Gwatkin met again with Garter who showed him his composition as drawn by the artist G. Cobb. The arms consisted of a white shield with a branch of nine maple leaves and the royal crown above. The crest was a gold beaver standing on a gold coronet of maple leaves “on a helmet mantled argent and gules” (white and red). The supporters were to be two lions or two beavers holding flags as in the present arms. The present motto and floral badges were also retained. Gwatkin noted that red maple leaves looked better than green ones and seemed quite pleased with the results. “They are not what we wanted; but they look very handsome, and I hope they will prove acceptable.”[55] On reading this description, one is struck by the similarities between Garter's design and Gwatkin's earlier one. His nine maple leaves are there as well as his beaver. Obviously, in his discussions with Garter, the major general had revived his own ideas forgetting what had been decided by the committee.

There were obviously conflicting views within the committee, and since the ultimate responsibility for giving Canada proper arms was that of Mulvey, he sometimes took initiatives of his own. On September 9, he wrote Rudyard Kipling who earlier had shown an interest in arms for Canada and had discussed the matter with Sir George Perley. He let Kipling know that he had read his humorous article entitled “A Displaie of New Heraldrie,” written in mock old English and signed Z. The article, published in the 3 November 1917 issue of The Spectator, pleaded for heraldic recognition of the Dominions' participation in the war.[56] Mulvey went on to explain how Canada had acquired the aggregate Dominion arms. He described the arms that the committee was now proposing and informed Kipling that their proposal had gone to the king. He further spoke of Gwatkin's visit and the opposition of Garter and asked for Kipling’s support: “Canada, as you stated in correspondence with Sir George Perley, has taken a part in the War which should entitle her to recognition, and this small recognition if granted at the present time would be very highly appreciated in Canada. The Arms would stand for all time to come as a national decoration for services in the war.”[57] Kipling had been away on holidays but acknowledged the letter and promised he would attempt to discover the specific objections to the proposed arms.[58]

In the meantime, Gwatkin, having returned to Canada on September 29, informed Cobb that he would soon receive the £10.00 owed him for his “beautiful rendering.” He further told him that the committee was charmed with his work, but that it still hoped the king would approve the royal version.[59] Garter evidently saw Gwatkin's letter, but made no comment regarding the committee's stance when he thanked Mulvey for sending Cobb's payment.[60]

On November 19, Milner wrote Devonshire, Governor General of Canada, informing him that before submitting the design to the king, he had consulted Garter who had made certain objections “which I need not trouble you with.” But, more importantly, he stated that Garter had understood from Gwatkin that a new design from the Canadian government “which would meet Garter's points” would be forthcoming. This new design was being awaited. Further, he had, through Stamfordham, sought the views of the king regarding proposed arms for Canada. The king it was learnt “would gladly give his consent to the proposed incorporation of portions of the Royal Arms into these Armorial Bearings.” However he did, as Chadwick had warned, “take exception to placing the Arms of the Sovereign under a Chief with Maple Leaves, and considers that the position should be reversed so that the arms come above the leaves.” The view was taken that the leaves, when placed above, debased the arms of the Sovereign and once this was explained to Canadian ministers, they would surely comply with His Majesty's wishes. Milner promised that, as soon as the revised sketch arrived, it would be placed before the king for his approval.[61] When Pope learned from a telegram [62] that Gwatkin had promised Garter a revised design, he remarked tersely: “I may observe that I did not understand that Garter's communication to General Gwatkin was in any sense official.”[63]

In the meantime, Gwatkin had seen the royal warrant granting arms to the Royal Military College of Canada and had noted that the royal crown had been authorized above the arms. He expressed to Mulvey his feeling that a similar crown should appear above Canada's arms and, for that matter, saw no reason why the lion should remain “un-crowned” as in the royal arms.[64] A bit later, he reported that Doughty had found a banner for France, a white cross on a blue field, and thought this flag would be well balanced with the cross of St. George on a white field which could replace the Union Jack.[65] The idea had considerable merit, both from a design and historical point of view and Mulvey thought so, but was hesitant because the other flags had not been objected to by the College of Arms.[66] Gwatkin did pose one small gesture which may have had some influence on the colours of the mantling in the arms of Canada. On December 16, he sent Garter's drawing to Mulvey explaining that if there was to be a helmet with Canada's arms, he proposed Cobb's sketch as a model.

On 4 March 1921, Garter inquired of Gwatkin whether the drawing he had taken back with him had given rise to a decision regarding the arms proposal.[67] Gwatkin reported that the committee had been contemplating arms where the lilies of France were replaced by the lions of England repeated in the fourth quarter, leaving the royal arms of the United Kingdom intact, but placing in the centre a white “escutcheon of pretence” displaying a red maple leaf. The royal crown was to be included above the coat of arms as had been done for the Royal Military College. Gwatkin warned Garter that the government might not concur with this proposal and a new one would then have to be made by the committee.[68] Gwatkin’s letter seemed intended to placate Garter, but Mulvey had already requested a rendering embodying the changes described by Gwatkin from the Toronto architect and talented heraldic artist, Alexander Scott Carter. Mulvey was sending him Cobbs drawing to show how such details as the shape of the shield and mantle could be handled. He also sent him the printed copy of Champagne’s rendering (fig. 8) with the caveat: “I may say that this lithograph was severely criticized because of its inartistic appearance. However this may be, the form was adopted in order to follow the Royal Arms as nearly as may be.”[69]

A draft of a submission to His Excellency describing the revised arms was also prepared on April 19 for approval by the committee. Mulvey was now pressing Carter for a draft of the arms to attach to the submission.[70] He was obviously hopeful that the new design would be approved by the committee and that, with this approval, the matter of Canadian arms would be smoothly resolved. Carter sent his draft drawing at 9 p. m., on April 18, and expressed his disappointment that he was not given time to prepare finished art which required a week. He was asking that the sketches and instructions be returned as soon as possible to prepare a finished drawing.[71]

It is certain that while in England, Gwatkin had discussed Garter’s opposition to the lilies of France and royal arms for Canada, but it seems that he did not fully understand the nature of Garter’s opposition. Correspondence in Canada always mentions his objections in the vaguest of terms: “certain objections” or “objections of a technical nature.” The revised arms being prepared by Carter were almost certainly devised by Gwatkin and endorsed by Mulvey to satisfy Gwatkin’s promise to Garter. Pope, who had always pressed for the arms as they were designed by the committee and had been annoyed with Gwatkin's performance in England, could not have been party to the revisions. Although the committee rarely kept minutes of its meetings, we know that the Gwatkin-Mulvey proposal was rejected when it met on April 20.[72] This was to be expected since Pope wanted to include French heritage on the shield and the new design did not do this.

On April 26, Pope had the drawing of the committee’s original proposal in hand. The maple leaves in base were red on a white field, something that, as we have seen, was not acceptable to Pope who reiterated his objections that the leaves formed “a blot on the whole blazon” and “that the symbol of a young country like Canada should speak of life and growth and vigour, rather than of decline, decay and approaching death.”[73] The leaves were duly made green, perhaps by Fortunat Champagne. In comparison with the rest of the rendering, the whole base of the shield with the green leaves is roughly drawn and coloured. On April 28, the amended drawing with the green leaves was being circulated to members of the committee for their signatures (fig. 9).[74]

One usual silly comment, at least from a heraldist's point of view, was made by P. D. Robertson, minister of labour, regarding the lion's tongue.[42] To his credit, however, he did admit that he could be wrong: “I would respectfully suggest that, inasmuch as the lion represents strength and dignity and as its head is adorned by the British Crown, it would be more appropriate if the lion's tongue were not exposed. There may, however, be some good reason why this change should not be made.”[43]