Royal Arms of Colonial Powers

1. France

The royal arms of France appeared on seals, coins, medals, liturgical vestments and vessels, and maps relating to French possessions in North America. They were displayed in public places, on and in many types of buildings, on the cornerstones of new constructions, on forts, at land claiming ceremonies, and at public festivities such as the planting of the maypole. Of course the royal arms were also displayed in other circumstances and on other objects. It is unfortunate that a number of these armorial treasures have not been publicized to the extent that they merit. Often armorial objects are photographed as a whole without taking a close-up of the arms themselves, although these can define something as being of royal origin and convey authority and authenticity to artefacts where they appear. The royal shield of France was sometimes placed side by side with other arms such as those of Navarre. Unlike the shield of England that was constantly undergoing changes, the shield of France did not vary during the period of New France. On the other hand, the accompaniments outside the shield fluctuated considerably, at times becoming quite complex (fig. 10).

The use of the royal arms of France at land claiming ceremonies and in other circumstances, civil and military, is dealt with in detail in a chapter of my work on Canada’s armorial bearings which can be consulted online on this site: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/chapter-1-european-heritage.html. The chapter also describes the royal arms and banner displayed during the French Huguenot attempts at colonization in Florida from 1562 to 1565.

The royal arms of France appeared on seals, coins, medals, liturgical vestments and vessels, and maps relating to French possessions in North America. They were displayed in public places, on and in many types of buildings, on the cornerstones of new constructions, on forts, at land claiming ceremonies, and at public festivities such as the planting of the maypole. Of course the royal arms were also displayed in other circumstances and on other objects. It is unfortunate that a number of these armorial treasures have not been publicized to the extent that they merit. Often armorial objects are photographed as a whole without taking a close-up of the arms themselves, although these can define something as being of royal origin and convey authority and authenticity to artefacts where they appear. The royal shield of France was sometimes placed side by side with other arms such as those of Navarre. Unlike the shield of England that was constantly undergoing changes, the shield of France did not vary during the period of New France. On the other hand, the accompaniments outside the shield fluctuated considerably, at times becoming quite complex (fig. 10).

The use of the royal arms of France at land claiming ceremonies and in other circumstances, civil and military, is dealt with in detail in a chapter of my work on Canada’s armorial bearings which can be consulted online on this site: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/chapter-1-european-heritage.html. The chapter also describes the royal arms and banner displayed during the French Huguenot attempts at colonization in Florida from 1562 to 1565.

Kings of France from the Discovery of Canada to the Treaty of Paris of 1763

Francis I (1515-1547)

Henry II (1547-1559)

Francis II (1559 -1560)

Charles IX (1560-1574)

Henry III (1574-1589)

Henry IV (1589-1610)

Louis XIII (1610-1643)

Louis XIV (1643-1715)

Louis XV (1715-1774)

After the explorations and colonization efforts of Jacques Cartier and Jean-François de La Rocque de Roberval from 1534 to 1543, the French did not return to the St. Lawrence River until 1603. The kings represented in green fall within that sixty-year interval.

Francis I (1515-1547)

Henry II (1547-1559)

Francis II (1559 -1560)

Charles IX (1560-1574)

Henry III (1574-1589)

Henry IV (1589-1610)

Louis XIII (1610-1643)

Louis XIV (1643-1715)

Louis XV (1715-1774)

After the explorations and colonization efforts of Jacques Cartier and Jean-François de La Rocque de Roberval from 1534 to 1543, the French did not return to the St. Lawrence River until 1603. The kings represented in green fall within that sixty-year interval.

Francis (François) I (1515-1547)

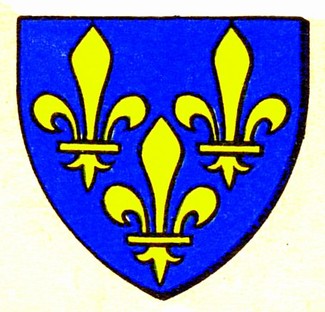

Fig. 1. Royal arms of France with only the shield and three fleurs-de-lis.

The first recorded instance of the royal arms of France being displayed on what is now Canadian soil occurred on 24 July 1534 when Jacques Cartier planted a large cross on the Gaspé coast to take possession of the surrounding lands. The arms of King Francis I of France, in whose name the ceremonial gesture took place, were attached to the cross. Many land claiming ceremonies of this type would follow, with the royal arms being fastened to crosses, posts, trees, or buried in the ground. The arms exhibited at such ceremonies were often improvised and presumably simple as in figure 1.

Henry (Henri) IV (1589-1610)

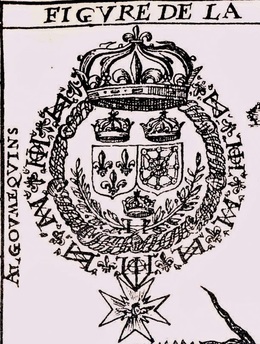

Fig. 2. Arms of France and Navarre side by side on a map in Marc Lescarbot, Histoire de la Nouvelle-France (Paris : Jean Millot, 1609).

It was during the reign of Henry IV that Pierre Du Gua de Monts established a settlement, first on the Île Ste-Croix (Dochet Island) in 1604 then at Port-Royal in 1605, and that Samuel de Champlain founded Quebec in 1608.

In figure 2, the two shields of France and Navarre, inside the collars of the Orders of St. Michael and of the Holy Ghost, are each ensigned (topped) by the royal crown. A third crown under the shields is above the letter H (the cipher of Henry IV) and is positioned over a wreath of laurel which partially encloses the shields. A fourth larger crown, partly over the collars, tops everything. This arrangement is unusual but not unique. It is found on the gilding irons used to impress the royal arms on the books of Henry III and Louis XIII, although in the case of Henry III, the second shield is not that of Navarre. It combines the arms of Poland with those of Lithuania, Henry III being King of France and Poland, and Grand Duke of Lithuania. Book bindings with the arms of Henry III and Louis XIII are found at: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b55005994b/f1.image and http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b550054807/f1.image. See also Hervé Pinoteau, La symbolique royale française Ve-XVIIIe siècles (Loudun: PSR Éditions, 2003): 474, 499.

The Navarre shield was placed alongside the shield of France by Henry IV in 1589. This arrangement persisted until 1792, although the arms of France alone were most frequent. For the evolution of the royal arms of France, see: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Armoiries_de_la_France.

In figure 2, the two shields of France and Navarre, inside the collars of the Orders of St. Michael and of the Holy Ghost, are each ensigned (topped) by the royal crown. A third crown under the shields is above the letter H (the cipher of Henry IV) and is positioned over a wreath of laurel which partially encloses the shields. A fourth larger crown, partly over the collars, tops everything. This arrangement is unusual but not unique. It is found on the gilding irons used to impress the royal arms on the books of Henry III and Louis XIII, although in the case of Henry III, the second shield is not that of Navarre. It combines the arms of Poland with those of Lithuania, Henry III being King of France and Poland, and Grand Duke of Lithuania. Book bindings with the arms of Henry III and Louis XIII are found at: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b55005994b/f1.image and http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b550054807/f1.image. See also Hervé Pinoteau, La symbolique royale française Ve-XVIIIe siècles (Loudun: PSR Éditions, 2003): 474, 499.

The Navarre shield was placed alongside the shield of France by Henry IV in 1589. This arrangement persisted until 1792, although the arms of France alone were most frequent. For the evolution of the royal arms of France, see: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Armoiries_de_la_France.

Louis XIII (1610-1643)

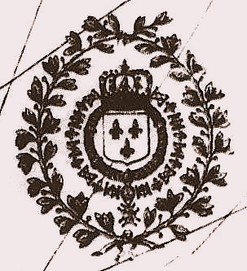

The Canadian career of Samuel de Champlain began during the reign of Henry IV and ended during that of Louis XIII. In figures 3 and 4, the shield with its three fleurs-de-lis is ensigned by the royal crown and surrounded by the collar of the Order of St. Michael within that of the Order of the Holy Ghost. In figure 3, the arms are inside a wreath of laurel. Similar arms appeared on a number of other maps relating to Canada.

Louis XIV (1643-1715)

Fig. 5. Reverse or counter seal of the Great Seal of Louis XIV of France. Appended to letters patent ennobling Robert Giffard, Seigneur of Beauport, 1658. Library and Archives Canada, Mg 18, H1, p. 2.

This seal of Louis XIV (fig. 5) shows the royal arms topped by the royal crown and supported by two angels. The collars of the Order of St. Michael and of the Order of the Holy Ghost are both absent.

Fig. 6. Seal of the Sovereign Council (Conseil souverain) of New France. Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

In 1663 Louis XIV placed New France under royal control and instituted an administrative structure based on French provinces. He introduced a Sovereign Council which acted as a court of appeal for civil and criminal matters arising in the lower courts. The council also regulated trade and public order and registered the king's edicts, ordinances, and commissions.

The royal arms of France were the main feature on the seal of the Sovereign Council (fig. 6). The shield with its three fleurs-de-lis is ensigned by the the royal crown and surrounded by the collar of the Order of St. Michael and that of the Order of the Holy Ghost. The inscription at the top is “Nouvelle France.” In 1703 the Sovereign Council became the Superior Council (Conseil supérieur), but the seal retained the same elements.

The royal arms of France were the main feature on the seal of the Sovereign Council (fig. 6). The shield with its three fleurs-de-lis is ensigned by the the royal crown and surrounded by the collar of the Order of St. Michael and that of the Order of the Holy Ghost. The inscription at the top is “Nouvelle France.” In 1703 the Sovereign Council became the Superior Council (Conseil supérieur), but the seal retained the same elements.

Fig. 7. Royal arms of France on the seal of the Superior Council of New France. The seal is applied to a judgment by the Superior Council confirming the rights of Juchereau Duchesnay over the Seigneury of Beauport, Quebec, 19 September 1742. Library and Archives Canada, MG 18, H18.

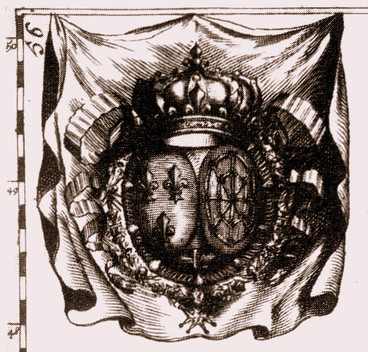

Fig. 8. Arms of France and Navarre inside the collars of the Orders of St. Michael and of the Holy Ghost, the whole ensigned by the royal crown. On a map entitled “Lac Supérieur et autres lieux où sont les Missions des Pères de la Compagnie de Jésus comprises sous le nom d’Outaouacs” in Claude Dablon, Relation de ce qui s'est passé de plus remarquable aux Missions des Pères de la Compagnie de Jésus, en la Nouvelle-France, les années 1671 & 1672 (Paris: M. Cramoisy, 1673), between p. 110 and 111. See an example of this map at: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k214104j/f131.image.

The Basilica-Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Québec has two liturgical vestments, both gifts of Louis XIV: a cope with the arms of France and Navarre and a richly embroidered chasuble with the same arms repeated on both sides of a cross, below the crossbar. An illustration of the cope is found in Pour assurer un avenir au passé. Des lieux de mémoire communs …, p. 54 on the site : http://www.cfqlmc.org/pdf/AssurerAvenir.pdf. The chasuble is illustrated in Pierre-Georges Roy, La ville de Québec sous le Régime français, vol. 2 (Quebec: Rédempti Paradis, 1930), between pp. 32 and 33. https://archive.org/details/lavilledequebecs02royp. Another chasuble offered to the Parish of Saint-Charles-Borromée, Province of Quebec, is embroidered with the arms of Maria Theresa of Austria, spouse of Louis XIV. They display marshalled (combined) on a same shield the royal arms of France on the left, alongside the arms of Habsburg Spain on the right. The chasuble can be seen on the site: http://www.ipir.ulaval.ca/fiche.php?id=229.

Fig. 9. The Kebeca Liberata Medal by Jean Mauger (reverse) celebrates Frontenac’s victory over Admiral Phipps at the siege of Quebec City in 1690. An allegorical female figure representing France holds the royal shield while a beaver below represents Canada. Library and Archives Canada, photo C-115685.

Fig. 10. The full royal achievement of arms of France. Illustration from Claude-François Ménestrier, Abrégé méthodique des principes héraldiques ou du véritable art du blason (Lyon: Benoist Coral, 1673), facing p. 180.

As can be seen in figure 10, the full achievement of the royal arms of France can be quite elaborate. This example includes the collars of the Order of St. Michael within that of the Order of the Holy Ghost, two angel supporters holding the Banner of France and wearing a dalmatic (tunic) bearing three fleurs-de-lis, a helmet with a sun face supporting the crown, a large pavilion adorned with ermine spots also royally crowned with sun rays emanating from the base of the crown, a scroll bearing the war cry of France "Montjoie Saint Denis!" (here spelt a little differently). Saint Denis is an important patron saint of France, but the etymology of Montjoie has not been clearly established. Above a gonfanon sprinkled with fleurs-de-lis, a scroll, bears the Latin motto “Lilia non laborant neque nent” which means “Lilies neither toil nor weave” and is from Luke 12:27. The verses underneath, "Seu venere solo, seu sunt hæc edita cælo, Hæc sunt digna solo, Lilia digna polo” (spelling modernized) were composed by the great Jesuit heraldist Claude-François Ménestrier and mean “Whether they are issued from the soil or come from the sky, the lilies are worthy of both the earth and the heavens.” The soil refers to lilies as real plants that grow in the earth and the heavens relates to the notion that the fleur-de-lis was brought by an angel to Clovis, the Merovingian King of the Franks. This complete achievement was probably never used in New France, but it is useful for comparison with simpler compositions.

Louis XV (1715-1774)

Fig. 11. Royal arms of France on a ½ sol (half sou), Louis XV, 1720. National Currency Collection, the Bank of Canada Museum. See the original image at:

http://www.bankofcanadamuseum.ca/collection/search/page/4?q=Louis+XIV&adv=1&co=0&ct=0&a=&s=&d1=&d2=.

http://www.bankofcanadamuseum.ca/collection/search/page/4?q=Louis+XIV&adv=1&co=0&ct=0&a=&s=&d1=&d2=.

Large quantities of these pieces (fig. 11) were shipped to New France in 1720. The royal arms also appeared on a number of coins circulating in the colony, some of which were struck specifically for the North American colonies, namely a gold and silver Louis and the 5-sol and 15-sol pieces.

Fig. 12. Type of treatment of the royal arms of France for gates, large buildings, forts, and public places. This trophy, attributed to the master sculptor Noël Levasseur, was taken from the gates of Quebec City in 1759 and gifted to the Royal Naval College of Portsmouth by Vice-Admiral Charles Saunders. It was returned to Canada in 1917 and is now held by the Canadian War Museum.

In a letter of 29 October 1725, the military engineer, Joseph-Gaspard Chaussegros de Léry, informed the French Minister of Colonies that the arms of His Majesty had not been displayed in the colony as they should have been. To remedy the situation, he had a number of them prepared by a sculptor and duly installed above the principal gates, buildings, forts and public places, namely at Château St. Louis (residence of the governor), the Palace (residence of the intendant), the stores, the barracks, Fort Chambly, as well as the guard-houses, prisons, and courts in Trois-Rivières and Montreal, so that the king’s sovereignty would be affirmed in his North American possessions. The arms were also installed in churches. From 1775, orders were given twice by the British government to remove all such arms.

2. Britain

The royal arms of Britain have known many modifications from 1497 when John Cabot hoisted the banner of King Henry VII on the east shores of North America to 1837 when Queen Victoria adopted the present version of the royal arms. All of these different compositions are linked to Canada in one way or another be it, for example, at land claiming ceremonies, on maces, seals, coins and medals, in the heading of official documents, on maps, on liturgical vessels, and as large wood carvings in such places as courts, churches or government buildings. The object here is not to compile a comprehensive inventory of instances where these arms appeared in a Canadian setting. This would be a Herculean task, all the more so that many of the arms on objects and in various places have not been properly photographed and brought to light. The intention in what follows is to show that all the arms illustrated below were used at one time or another in connection with Canada but not necessarily in connection with every sovereign.

The royal arms of Britain have known many modifications from 1497 when John Cabot hoisted the banner of King Henry VII on the east shores of North America to 1837 when Queen Victoria adopted the present version of the royal arms. All of these different compositions are linked to Canada in one way or another be it, for example, at land claiming ceremonies, on maces, seals, coins and medals, in the heading of official documents, on maps, on liturgical vessels, and as large wood carvings in such places as courts, churches or government buildings. The object here is not to compile a comprehensive inventory of instances where these arms appeared in a Canadian setting. This would be a Herculean task, all the more so that many of the arms on objects and in various places have not been properly photographed and brought to light. The intention in what follows is to show that all the arms illustrated below were used at one time or another in connection with Canada but not necessarily in connection with every sovereign.

British Royal Houses from the Age of Discovery to the Present

The Tudors (1485-1603)

The Stuarts (1603-1649) and (1660-1714)

House of Hanover (1714-1901)

House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha (1901-1910)

The Windsors (1910- today)

The Tudors (1485-1603)

The Stuarts (1603-1649) and (1660-1714)

House of Hanover (1714-1901)

House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha (1901-1910)

The Windsors (1910- today)

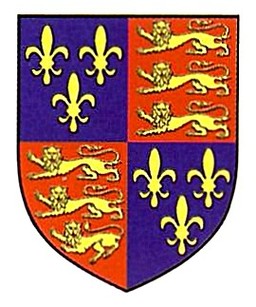

1406-1603

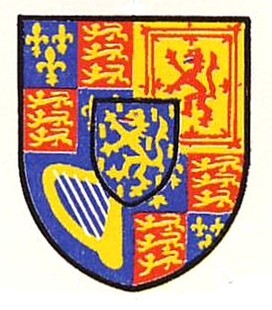

Fig. 13. British history in Canada begins with the landing of John Cabot on the East Coast of North America in 1497 at the time of the Tudor King Henry VII (1485-1509). Subsequent British sovereigns who bore these arms were Henry VIII (1509-1547), Edward VI (1547-1553), Mary I (1553-1558), and Elizabeth I (1558-1603).

It is not certain where John Cabot landed on the North American coast in 1497. Proposed places have been Newfoundland, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Labrador or Maine. The flag he raised has been described as the bandera regia (bandiera regia), in other words the royal banner or standard of King Henry VII of England, which at the time combined the three fleurs-de-lis of France with the three lions of England, both repeated twice on the shield as in figure 13. (Conrad Swan Canada: Symbols of Sovereignty p. 9 and p. 76, fig. 4.7). A rowboat used during Frobisher’s expedition to Baffin Island in 1577 carried the banner of St. George (a red cross on a white field) bearing in centre the shield of Elizabeth I which was the same as figure 13: (http://www.historymuseum.ca/cmc/exhibitions/hist/frobisher/fr57702e.shtml). The same arms were affixed to a post when Sir Humphrey Gilbert claimed Newfoundland in 1583, again during the reign of Elizabeth I.

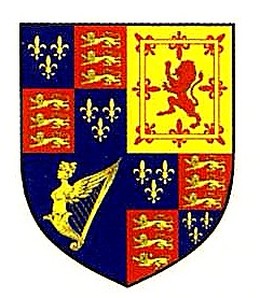

1603-1688 and 1702-1707

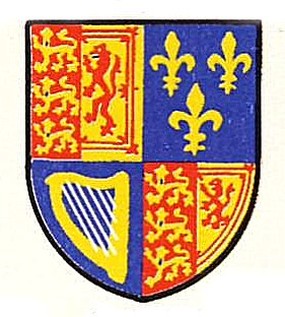

Fig. 14. British sovereigns who bore these arms were James I of England and VI of Scotland (1603-1625), Charles I (1625-1649), Charles II (1660-1685), James II of England and VII of Scotland (1685-1688) and Queen Anne from 1702-1707.

In the spring of 1613, Sir Thomas Button, who had wintered at the mouth of the Nelson River, planted a cross and a post and affixed thereto the arms of England, taking possession of the territory. At Port Nelson in 1670, Charles Bayly went ashore, nailed the arms of Charles II engraved in brass to a tree, and laid claim to the territory. The Great Seal of the Realm of Charles II is appended to the royal charter creating the Hudson’s Company (Company of Adventurers) in 1670: http://journals.sfu.ca/archivar/index.php/archivaria/article/viewFile/12230/13255. On Charles II’s third Great Seal, the royal arms appear on the obverse above the throne. See Conrad Swan, Canada Symbols of Sovereignty: 25.

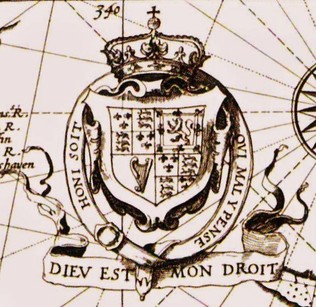

Fig. 15. The shield of arms of James I, King of England, Scotland, and Ireland with the fleurs-de-lis expressing pretention to the throne of France. On a map entitled « Tabula Nautica » illustrating the voyages of Henry Hudson, 1610-1611, published in Hesselius Gerardus, Descriptio ac delineatio geographica detectionis freti …, Amsterdam, 1612. Library and Archives Canada, NMC 19228.

Figs. 16-17. The obverse and reverse of the Great Seal of Charles I as King of Scotland. Appended to the charter granting the title of baronet and a tract of land in Nova Scotia to Sir Duncan Campbell of Glenorchy, 1625. Library and Archives Canada, MG 18, F 36, photos C – 131775 and C – 131774.

On the reverse appears the achievement of arms of Charles I as King of Scotland (fig. 17). The arms of Scotland are in the 1st and 4th quarters, those of England in the 2d quarter, and Ireland in the 3d. The flag of Scotland (saltire cross of St. Andrew) is on the left and the flag of England (cross of St. George) is on the right. The unicorn of Scotland is on the left and the lion on the right, thus reversing their positions as depicted in the royal arms of England. The full achievements of arms of Charles I as used as King of England and as King of Scotland can be seen on the site: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_I_of_England.

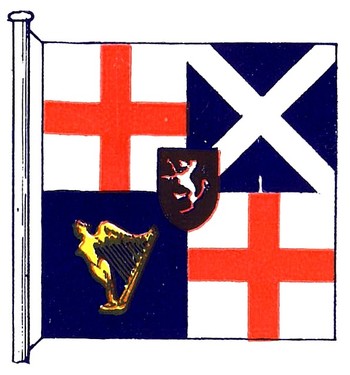

1653-1659

Fig. 18. The banner of Oliver and Richard Cromwell replicating the arms that they displayed during their time in office. The white lion on a black shield in centre represents the personal arms of the Cromwells. Their complete arms as Lord Protectors can be viewed on this site: http://hoocher.com/Charles_II_of_England/Charles_II_of_England.htm.

The civil war between the Parliamentarians and Royalists broke out in 1642. The victory of the Parliamentarians in 1649 led to the beheading of Charles I on 30 January 1649 and the abolishment of the monarchy by Parliament on 17 March 1649. Charles II was crowned King of Scotland in 1651 and that same year was defeated by Cromwell’s forces at Worcester. Cromwell dissolved Parliament in 1653 and ruled as Lord Protector of England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland until his death in September 1658. He was replaced by his son Richard who remained in office until 25 May 1659. Charles II claimed the English throne on 29 May 1660 and was crowned King of England on 23 April 1661 (see fig. 14).

Fig. 19. Seal of Oliver Cromwell applied to a letter from Cromwell to Captain John Leveret concerning Acadia, London, 18 September 1656. The motto around the edge Pax Quæritur Bello is that of Cromwell and means “Peace is achieved by War.” Library and Archives Canada, MG 18, F4, photo C – 101676.

Mid-1689-1702

Fig. 20. This shield was that of William III and Mary II (1689-1694) and William alone (1694-1702).

In mid-1689, Mary and William briefly made use of two other arrangements for their arms. One is the same as figure 20, except that a second harp of Ireland replaces the red lion rampant of Scotland in the second quarter. The other is composed of the quartered arms of England, Scotland, Ireland, and France, as in the Arms of Canada but without the sprig of maple. All three shields have the escutcheon of Nassau in centre. The author has found no evidence that the mid-1689 shields were ever used in Canada. From 1702 to 1707, Queen Anne bore the arms of her father James II (fig. 14).

A wood carving of the full achievement of arms of William III and Mary II (not impaled with the arms of the Queen), is found in All Saints Anglican Church, St. Andrews, New Brunswick. The artefact has a strong connection with the Loyalist clergy since the royal gift, originally made to St. Paul’s in Wallingford (Connecticut), was brought to Canada by the Reverend Samuel Andrews, Rector of St. Paul’s, who arrived at St. Andrews in 1786. A communion service in Trinity Anglican Church, Saint John, New Brunswick, includes an alms basin engraved with the arms of William III and the cipher G R. These two items are described and illustrated in Robert Pichette, “New Brunswick’s Royal Heraldry Legacy” in Heraldry in Canada / L’Héraldique au Canada 49, no. 1-2 (2015): 17-18, 20-21.

A wood carving of the full achievement of arms of William III and Mary II (not impaled with the arms of the Queen), is found in All Saints Anglican Church, St. Andrews, New Brunswick. The artefact has a strong connection with the Loyalist clergy since the royal gift, originally made to St. Paul’s in Wallingford (Connecticut), was brought to Canada by the Reverend Samuel Andrews, Rector of St. Paul’s, who arrived at St. Andrews in 1786. A communion service in Trinity Anglican Church, Saint John, New Brunswick, includes an alms basin engraved with the arms of William III and the cipher G R. These two items are described and illustrated in Robert Pichette, “New Brunswick’s Royal Heraldry Legacy” in Heraldry in Canada / L’Héraldique au Canada 49, no. 1-2 (2015): 17-18, 20-21.

1707-1714

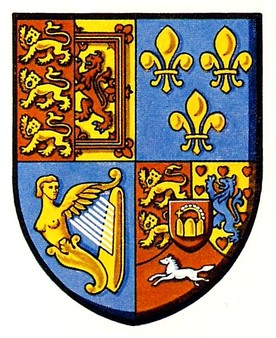

Fig. 21. Queen Anne (1702-1714) adopted these second arms following the Act of Union between England and Scotland in 1707. Her first arms from 1702 to1707 were as in figure 14.

The treasures of St. Paul’s Church, Halifax, Nova Scotia, include a flagon and alms basin engraved with the second arms of Queen Anne (1707-1714) which consisted of the shield, the garter with motto, and the crown. Engraved over the “A” for Anne (still discernable) is a “G” for George. See St. Paul’s Journal, Advent-Christmas 2010: 5-7: http://www.stpaulshalifax.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/2010-Advent-SPJ.pdf and Swan, Canada: Symbols of Sovereignty: 52-53. In 1711 Queen Anne offered the Mohawks a communion service comprising a footed paten, a chalice, and a flagon, all engraved with her second arms and cipher. These precious gifts are housed in Christ Church, Her Majesty's Chapel of the Mohawks near Deseronto, Ontario, which is administered by the Anglican Parish of Tyendinaga. See: http://www.parishoftyendinaga.org/chapelroyal.htm.

1714-1801

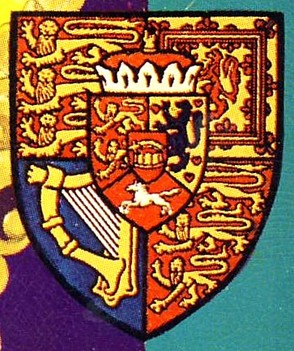

Fig. 22. Shield of arms as borne by George I (1714-1727), George II (1727-1760), and George III from 1760 until 1801. George I acceded to the throne of Hanover in 1714. The arms of the fourth quarter (lower right) are those of the Kingdom of Hanover.

A large woodcarving of the arms of George I is seen above the West door in Trinity Anglican Church, Saint John, New Brunswick. See: Robert Pichette, “New Brunswick’s Royal Heraldry Legacy” in Heraldry in Canada / L’Héraldique au Canada 49, no. 1-2 (2015): 18-19; Rev. Canon Brigstocke, History of Trinity Church, Saint John, New Brunswick, 1791-1891 (Saint John; J. & A. McMillan, 1892): 31-34: https://archive.org/stream/cihm_00274#page/31/mode/2up, and Swan, Canada: Symbols of Sovereignty, colour plate 11.2. Another example of these arms appears on an Indian Chief silver medal in the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto (949.69.3), Swan, op. cit.: 54, plate 3.12. The same shield at the time of George III is featured on a painting in St. Luke's Anglican Church Municipal Heritage Building, Placentia, Newfoundland and Labrador: http://www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/image-image.aspx?id=6247#i3. In June 1766, Governor General Murray brought to Canada a small silver chalice and alms dish bearing the above royal arms of King George III with garter and crown added to the shield. Murray presented these gifts in the name of the king to the Holy Trinity Anglican Cathedral of Quebec City: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Murray_Plate_being_that_presented_to_the_Anglican_Parish_of_Quebec_by_King_George_III_through_General_James_Murray,_Governor_of_Canada_on_the_27_June,_1766_(HS85-10-13407).jpg. Canadian provincial seals also displayed these same arms. See: Conrad Swan, op. cit.: 106-07, 125, 127, 143, 150, 164.

1801-1816

Fig. 23. In these arms of George III from 1801 to 1816, the central escutcheon is topped with the Hanoverian electoral bonnet.

One of the finest gifts of altar vessels was made by George III to the Holy Trinity Anglican Cathedral of Quebec City in1804. It consists of twelve pieces of solid silver all embossed with the full royal arms as borne from 1801 to1816 and the arms of the diocese, site: https://www.pinterest.com/cathedrale/silver/. An Indian Chief silver medal in the Royal Ontario Museum; a woodcarving on the speaker’s chair of the former Legislative Council (now in a committee room), and the Senate mace of Canada all display these arms. See Conrad Swan, Canada: Symbols of Sovereignty: 54-6 and Robert Pichette, “New Brunswick’s Royal Heraldry Legacy” in Heraldry in Canada / L’Héraldique au Canada 49, no. 1-2 (2015): 21-2.

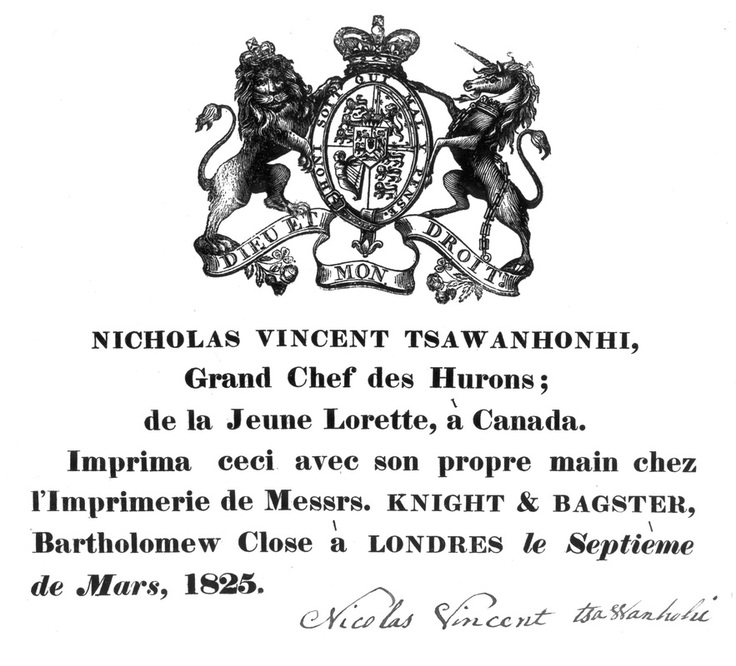

Fig. 24. Handbill printed by Nicolas Vincent Tsawanhohi, Grand Chief of the Hurons of Lorette. Library and Archives Canada, photo C – 111475.

Although Nicolas Vincent Tsawanhohi, Grand Chief of the Hurons of Lorette from 1811 to 1844, printed this handbill in 1825, the arms are clearly those of 1801-1816 with the electoral bonnet of Hanover (fig. 26) rather than the crown which came into use after Hanover became a kingdom in 1814. It is of interest that the name is printed “Nicholas” instead of “Nicolas” and “Tsawanhonhi” whereas the signature is spelt “tsaWanhohi.” It also reads “son proper main” rather than “sa propre main” and “à Canada” instead of “au Canada.”

Fig. 25. Detail of figure 24 showing only the arms.

Fig. 26. Detail of the arms (fig. 25) showing that it is the electoral bonnet and not the royal crown which appears on top of the escutcheon of Hanover. Such a bonnet is termed a cap of maintenance in heraldry.

1816-1837

Fig. 27. In 1814 Hanover became a kingdom, which resulted in the electoral bonnet on the escutcheon of Hanover being replaced by a royal crown two years later. This version of the royal arms was borne by George III from 1816 to 1820, George IV (1820-1830), and William IV (1830-1837).

A large number of the colonial or provincial seals of George III, George IV, and William IV displayed these arms. See Conrad Swan, Canada: Symbols of Sovereignty, colour plate 13.1 and pp. 88, 108. 111, 128-29, 144, 150, 152-53, 166-67. The royal arms of George IV are seen on a panel between two allegorical figures, one representing law, the other justice, behind the justice’s bench in the Appeal Court of New Brunswick in Fredericton.

Figs. 28-29. This George IV one quarter dollar, dated 1822, was struck in Great Britain for use in the British West Indies. It arrived in Canada through trade. The arms on the obverse are those of the king as in figure 27. National Currency Collection, the Bank of Canada Museum: http://www.bankofcanadamuseum.ca/collection/artefact/view/1964.0065.00014.000/great-britain-george-iv-14-dollar-1822.

Figs. 30-31. Brass female die of the seal of the Commander of the Forces in British North America bearing the royal arms as composed from 1816 to 1837. In figure 31, the image was flipped to create a positive picture for easier reading. Library and Archives Canada, photo C – 133328.

This seal of the Commander of the Forces in British North America dates from 1816 to 1837. The date is confirmed by the royal crown on top of the Hanoverian escutcheon as in figure 27. Being of a generic nature, this seal could have been used by several incumbents of the office. When Victoria became Queen on 20 June 1837, the Hanoverian escutcheon was removed from the centre of the royal arms which means that the above seal is prior to that date but no earlier than 1816.

1837 to present day.

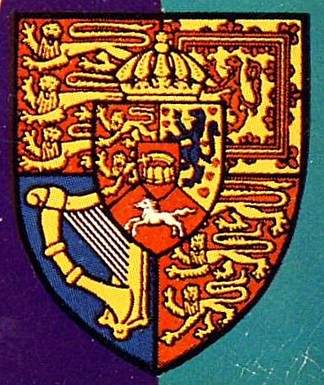

Fig. 32. Royal arms as borne by Queen Victoria (1867-1901), Edward VII (1901-1910), George V (1910-1936), Edward VIII (1936), George VI (1936-1952), Elizabeth II (1952 ―). From Fox-Davies, The Art of Heraldry (1904), plate CXIV.

When Queen Victoria ascended the throne, Salic Law prevented her from succeeding to the crown of Hanover. As a result the shield of the Kingdom of Hanover was eliminated from the royal arms of England. The royal arms as borne from 1837 to this day are found in numerous places in Canada. A few monumental examples are those on the tympanum of the portico of Charlotte County Court House in St. Andrews, New Brunswick (http://www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/image-image.aspx?id=7739#i1) and on the tympanum of the main entrance to Rideau Hall completed by the Duke of Connaught in 1913 (http://www.yyzphotofx.com/2008/12/rideau_hall.html).

Fig. 33. The royal arms are frequently depicted without a helmet, mantling or crest. The crown is then placed directly on the garter Belt. Wedgwood plate, 1911. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

Fig. 34. Here the royal arms are depicted with shield, crown, and supporters only. Sugar bowl by The Foley China (Wileman & Co), England, 1897. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

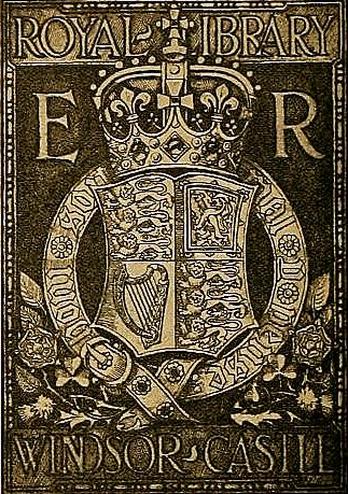

Fig. 35 Royal bookplate by G. W. Eve, R.E. The royal arms are reduced to the shield, the garter with motto, and the royal crown, something which is not uncommon. From Fox-Davies, The Art of Heraldry (1904): 464.

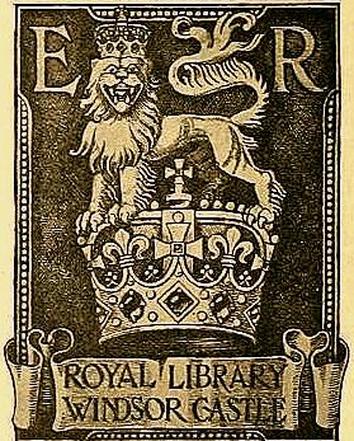

Fig. 36. Royal bookplate by G. W. Eve, R.E. The royal crest can also appear alone as is the case for the crest of armorial bearings in general. From Fox-Davies, The Art of Heraldry (1904): 464.

Further Reading

Cogné, Daniel, and Patricia Kennedy. Lasting Impressions: Seals in our History. Ottawa: National Archives of Canada, 1991.

Kennedy, Patricia. “Impressions of State Authority” in Genealogica & Heraldica: Proceedings of the 22nd International Congress of Genealogical and Heraldic Sciences in Ottawa, August 18-23, 1996. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1998: 373-84.

Pichette, Robert. “New Brunswick’s Royal Heraldry Legacy.” Heraldry in Canada / L’Héraldique au Canada 49, no. 1-2 (2015): 17-30.

Idem, “Les armoiries de souveraineté et de possession françaises en Amérique” at: http://pages.infinit.net/cerame/heraldicamerica/etudes/souverainete.htm.

Swan, Conrad. Canada: Symbols of Sovereignty. Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1977.

Vachon, Auguste. “European Heritage.” Chapter I of Canada’s Coat of Arms: Defining a Country within an Empire:

http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/chapter-1-european-heritage.html.

Cogné, Daniel, and Patricia Kennedy. Lasting Impressions: Seals in our History. Ottawa: National Archives of Canada, 1991.

Kennedy, Patricia. “Impressions of State Authority” in Genealogica & Heraldica: Proceedings of the 22nd International Congress of Genealogical and Heraldic Sciences in Ottawa, August 18-23, 1996. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1998: 373-84.

Pichette, Robert. “New Brunswick’s Royal Heraldry Legacy.” Heraldry in Canada / L’Héraldique au Canada 49, no. 1-2 (2015): 17-30.

Idem, “Les armoiries de souveraineté et de possession françaises en Amérique” at: http://pages.infinit.net/cerame/heraldicamerica/etudes/souverainete.htm.

Swan, Conrad. Canada: Symbols of Sovereignty. Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1977.

Vachon, Auguste. “European Heritage.” Chapter I of Canada’s Coat of Arms: Defining a Country within an Empire:

http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/chapter-1-european-heritage.html.

Nota Bene

All the websites were accessed on 14 May 2016.

All the websites were accessed on 14 May 2016.