Entalenté à parler d’armes

Auguste Vachon, Outaouais Herald Emeritus

Revised and augmented version of an article first published in Heraldry in Canada/L’Héraldique au Canada 47, no. 3-4 (2013): 44.

When I first encountered the motto that the Heraldry Society (England) adopted in 1957, Entalenté à parler d’armes, I was both fascinated and intrigued. My first impression was that it meant to have the knowledge to speak of armorial bearings or possibly the ability to blazon (describe coats of arms in heraldic language). Recently I found the same words in a long poem by Jacques Bretel or Brétex describing the tournament at Chauvency (Lorraine) in 1285, and was curious to re-examine the meaning of the phrase. For my analysis, I used two published versions of his poem. [1] The verses 804-5 read as follows: Hyraus resont entalenté / A parler d’armes … Several words of this phrase require explanations. Hyraus is hérauts, in English heralds. Resont is composed of sont meaning “are” prefixed by re meaning “again,” the full translation being “are again.” In medieval French, entalenté has nothing to do with talent or ability. It means to be willing, desirous, inclined, determined or enthusiastic to do something; to be eager, strongly moved or even have a burning desire to perform some action. [2]

Parler d’armes could possibly include blazoning, but the use of the same phrase in another section of the poem points to a more general meaning. At one point, Bretel meets the herald Bruiant (loud) who removes his tabard painted with arms (Bruiant despoille sa garnaiche, / Que d’armes estoit painturée; - verses 293-94). Three verses down, the poet informs us that Bruiant wants to speak to him of arms and chivalry (Pour ce qu’il suet [souhaite] parler à moi / D’armes et de chevalerie). Here parler de is used in the sense that it has today, namely “to speak of” or “converse about.” It is clear that the meaning “to blazon” could not be applied to both arms and chivalry in the same phrase. In other words, one can blazon arms but not chivalry. In modern French, verses 804-5 can be rendered by Les hérauts sont à nouveau désireux de parler d’armes, which can translate as “Heralds are again eager to speak of arms.” The motto Entalenté à parler d’armes would then become “Eager to speak of arms.” The translation “Equipped to speak of arms” in L.G. Pine’s A Dictionary of Mottoes does not render the medieval meaning of the word entalenté, but it is close to the perception I originally had of this term.

Parler d’armes could possibly include blazoning, but the use of the same phrase in another section of the poem points to a more general meaning. At one point, Bretel meets the herald Bruiant (loud) who removes his tabard painted with arms (Bruiant despoille sa garnaiche, / Que d’armes estoit painturée; - verses 293-94). Three verses down, the poet informs us that Bruiant wants to speak to him of arms and chivalry (Pour ce qu’il suet [souhaite] parler à moi / D’armes et de chevalerie). Here parler de is used in the sense that it has today, namely “to speak of” or “converse about.” It is clear that the meaning “to blazon” could not be applied to both arms and chivalry in the same phrase. In other words, one can blazon arms but not chivalry. In modern French, verses 804-5 can be rendered by Les hérauts sont à nouveau désireux de parler d’armes, which can translate as “Heralds are again eager to speak of arms.” The motto Entalenté à parler d’armes would then become “Eager to speak of arms.” The translation “Equipped to speak of arms” in L.G. Pine’s A Dictionary of Mottoes does not render the medieval meaning of the word entalenté, but it is close to the perception I originally had of this term.

Notes

[1] Jacques Bretex ou Bretiaus, Le tournoi de Chauvency, publié par Gaëtan Hecq (Mons: Dequesne-Masquillier & Fils, 1898) and Les tournois de Chauvenci donnés vers la fin du treizième siècle, décrits par Jacques Brétex, 1285, annotated by the late Philibert Delmotte (Valenciennes: A. Prignet, 1835).

[2] To determine the meaning of entalenté, I have looked at several medieval excerpts containing this word and consulted a number of ancient language dictionaries, for instance: Pierre Borel, Dictionnaire des termes du vieux françois ou trésor des recherches & antiquités gauloises & françoises, revised and augmented by Léopold Favre, vol. 1 (Niort : L. Favre, 1882) : 240; Jean-Baptiste de la Curne de Sainte-Palaye, Dictionnaire historique de l'ancien langage françois ou glossaire de la langue françoise depuis son origine jusqu'au siècle de Louis XIV, vol. 5 (Niort : L. Favre, 1882): 405-06; Frédéric Godefroy, Dictionnaire de l'ancienne langue française et de tous ses dialectes du IXe au XVe siècle, vol. 3 (Paris: F. Vieweg, 1884): 248-49.

[1] Jacques Bretex ou Bretiaus, Le tournoi de Chauvency, publié par Gaëtan Hecq (Mons: Dequesne-Masquillier & Fils, 1898) and Les tournois de Chauvenci donnés vers la fin du treizième siècle, décrits par Jacques Brétex, 1285, annotated by the late Philibert Delmotte (Valenciennes: A. Prignet, 1835).

[2] To determine the meaning of entalenté, I have looked at several medieval excerpts containing this word and consulted a number of ancient language dictionaries, for instance: Pierre Borel, Dictionnaire des termes du vieux françois ou trésor des recherches & antiquités gauloises & françoises, revised and augmented by Léopold Favre, vol. 1 (Niort : L. Favre, 1882) : 240; Jean-Baptiste de la Curne de Sainte-Palaye, Dictionnaire historique de l'ancien langage françois ou glossaire de la langue françoise depuis son origine jusqu'au siècle de Louis XIV, vol. 5 (Niort : L. Favre, 1882): 405-06; Frédéric Godefroy, Dictionnaire de l'ancienne langue française et de tous ses dialectes du IXe au XVe siècle, vol. 3 (Paris: F. Vieweg, 1884): 248-49.

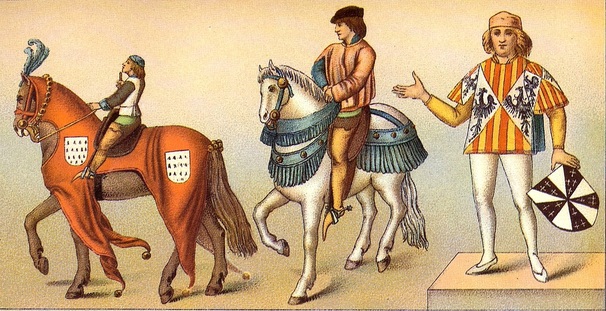

On the right, the Sicily Herald in the service of King Alfonso of Aragon around 1420, wearing a tabard combining the arms of Aragon and Hohenstaufen. At that time, Sicily belonged to the King of Aragon. Auguste Racinet, Le costume historique, vol. 4 (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1888), plate DC in “Moyen-Âge – XVe siècle” section. A copy of this work is found at: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6544837j/f119.image accessed 2 May 2016.