Chapter I

BIRTH AND SURVIVAL OF HERALDRY

Most people are vaguely aware that heraldic emblems were displayed on the shields and armour of knights during the Middle Ages and that somehow they have survived to this day. A fascinating but elusive quest is the search for the catalyst or spark that rather suddenly caused heraldry to come into being. We know for instance that warriors fought in armour with decorated shields and helmets since Antiquity, a time when pictorial seals, sometimes very close to medieval heraldic seals, were also used. Yet that period never developed a systematic way of creating, describing and recording emblems. How heraldry managed to survive over the centuries is an intriguing story, but also a rather complex one that goes hand in hand with historical developments in the western world. With time the Middle Ages developed an emblematic system that went far beyond simple identifying imagery on a shield. It created a means of recognizing individuals within a family, of identifying corporate entities, and evolved a specialized language to describe the content of the shield and experts of the discipline called heralds. In Canada the first recorded arms came from Europe. Much of the freely created heraldry had the characteristics of popular or naïve art. In 1988 the country was conferred the power to grant arms with the creation of the Canadian Heraldic Authority. This event is increasingly changing the Canadian Heraldic scene.

Origins

At first historians sought the origins of heraldry among the Assyrians, the Egyptians, the Greeks and the Romans. The more imaginative theorists went so far as to attribute its invention to Adam, Noah, Alexander the Great or Julius Caesar. Hopefully Adam and Eve had a sufficiently harmonious relationship that they had no need to raise a flag each time they approached one another. This ironic remark highlights the fact that symbols are needed when humans live in society. There is a need for groups of humans to express their identity as opposed to other groups and, within the groups themselves, to have personal identifying marks conveying the status and authority of outstanding warriors or leaders. In fact the collective and the individual seem to be the two major poles of any symbological system including heraldic ones.

Some warriors in Antiquity did make use of devices close to those of the medieval knight. This is the case of a late sixth century B.C. tile fragment showing two warriors attired for combat (fig. 1). The warrior on the left carries a round shield with an ochre border and, in centre, a saltire (X cross) over which is another cross formed of four black branches of a tree or plant. These in fact look a lot like the fir twigs now used in modern heraldry. Topping his helmet is a type of crest which appears somewhat like a vol (the expanded wings of a bird), but may just be a fan added for extra protection. The warrior on the right likewise holds a round shield with an ochre saltire. The spaces between the arms of the saltire are black and strewn with small whitish rectangles not unlike the billets found in heraldry today. The border is divided into two colours by a toothed line called dancetty in the modern language of heraldry. His crest may be an animal or again a protective addition.

Origins

At first historians sought the origins of heraldry among the Assyrians, the Egyptians, the Greeks and the Romans. The more imaginative theorists went so far as to attribute its invention to Adam, Noah, Alexander the Great or Julius Caesar. Hopefully Adam and Eve had a sufficiently harmonious relationship that they had no need to raise a flag each time they approached one another. This ironic remark highlights the fact that symbols are needed when humans live in society. There is a need for groups of humans to express their identity as opposed to other groups and, within the groups themselves, to have personal identifying marks conveying the status and authority of outstanding warriors or leaders. In fact the collective and the individual seem to be the two major poles of any symbological system including heraldic ones.

Some warriors in Antiquity did make use of devices close to those of the medieval knight. This is the case of a late sixth century B.C. tile fragment showing two warriors attired for combat (fig. 1). The warrior on the left carries a round shield with an ochre border and, in centre, a saltire (X cross) over which is another cross formed of four black branches of a tree or plant. These in fact look a lot like the fir twigs now used in modern heraldry. Topping his helmet is a type of crest which appears somewhat like a vol (the expanded wings of a bird), but may just be a fan added for extra protection. The warrior on the right likewise holds a round shield with an ochre saltire. The spaces between the arms of the saltire are black and strewn with small whitish rectangles not unlike the billets found in heraldry today. The border is divided into two colours by a toothed line called dancetty in the modern language of heraldry. His crest may be an animal or again a protective addition.

Fig. 1 Two warriors, late sixth century B.C. Fragments of painted terra-cotta relief tile from Pazarli, Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara, Turkey.

Many Greek shields display various animals, animal parts and geometrical shapes as in modern heraldry. These seem to be individual marks and, apart from a decorative role, probably served for recognition. A depiction of a sixth century B.C. vase in the Musée du Louvre shows a Greek warrior clearly displaying a large scorpion on his shield. Another vase depiction of the same period, also in the Louvre, shows Achilles and Ajax playing dice. Achilles has on his shield a grotesque human face between a serpent above and a leopard below, while Ajax bears a similar shield with the face between two serpents.[1] Here the shields, though individualized, are close enough in design to indicate some link between the two warriors, who were both Greek soldiers fighting the Trojans. An Etruscan oinochoe (wine pitcher) found at Tragliatella in Italy and kept in the Palazzo dei Conservatori in Rome (Inv. Mob. 358) shows a whole contingent of soldiers all displaying a boar passant (walking by) on their shields. Here the boar is clearly the mark of an entire unit indicating that they are fighting together.[2] The use of the shield of their lord for a whole group of combatants resurfaces at times in the Middle Ages, particularly during the feudal period in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, though shields tended as a rule to be individualized.[3]

Of course the nations of Antiquity, like those of today, had their own symbology. Most of these seem to relate to clans or families. In aspects of these ancient systems, we find striking resemblances to heraldry, although comparative analysis between ancient forms and modern heraldic art also brings out significant differences. We should therefore avoid using the word heraldry to describe emblematic systems that are pictorial and serve similar purposes as heraldry but are similar in a general sense only. Profound differences are highlighted by the fact that a person with in depth knowledge of heraldry may have only very diffuse notions concerning, for instance the Japanese mon or the totemic art of North American First Nations. As we shall see, heraldry is a highly specific system with its own unique structure and language.

Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, Baron de Lahontan, who was stationed in New France with the French troops from ca. 1683 to 1693, scoffs at the totems of the Amerindians. Instead of trying to understand them more fully, he scornfully dismisses their “heraldry” as risible and a product of the general ignorance of natives in scientific matters. He describes their totems as fanciful, ridiculous figures that they engrave into the bark of a tree to record certain exploits or as the distinguishing mark of a nation or a leader (fig. 2 & 3).

“After a perusal of the former Accounts I sent you of the Ignorance of the Savages with reference to Sciences, you will not think it strange that they are unacquainted with Heraldry. The Figures you have represented in this Cut will certainly appear ridiculous to you, and indeed they are nothing less: But after all you’ll content yourself with excusing these poor Wretches, without rallying upon their extravagant Fancies.”[4]

Of course the nations of Antiquity, like those of today, had their own symbology. Most of these seem to relate to clans or families. In aspects of these ancient systems, we find striking resemblances to heraldry, although comparative analysis between ancient forms and modern heraldic art also brings out significant differences. We should therefore avoid using the word heraldry to describe emblematic systems that are pictorial and serve similar purposes as heraldry but are similar in a general sense only. Profound differences are highlighted by the fact that a person with in depth knowledge of heraldry may have only very diffuse notions concerning, for instance the Japanese mon or the totemic art of North American First Nations. As we shall see, heraldry is a highly specific system with its own unique structure and language.

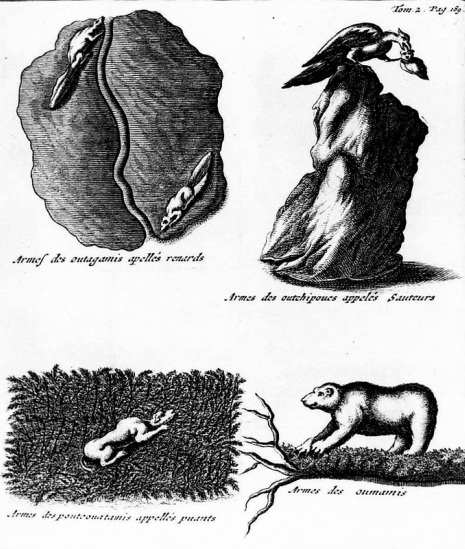

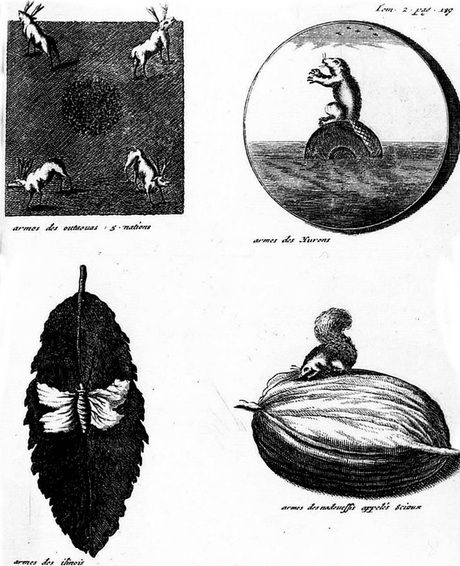

Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, Baron de Lahontan, who was stationed in New France with the French troops from ca. 1683 to 1693, scoffs at the totems of the Amerindians. Instead of trying to understand them more fully, he scornfully dismisses their “heraldry” as risible and a product of the general ignorance of natives in scientific matters. He describes their totems as fanciful, ridiculous figures that they engrave into the bark of a tree to record certain exploits or as the distinguishing mark of a nation or a leader (fig. 2 & 3).

“After a perusal of the former Accounts I sent you of the Ignorance of the Savages with reference to Sciences, you will not think it strange that they are unacquainted with Heraldry. The Figures you have represented in this Cut will certainly appear ridiculous to you, and indeed they are nothing less: But after all you’ll content yourself with excusing these poor Wretches, without rallying upon their extravagant Fancies.”[4]

Fig. 2 Arms of Ottawas, Hurons, Illinese, Nadouesis (Sioux) according to Louis-Armand de Lahontan, Mémoires de l’Amérique septentrionale, The Hague, 1715, following p. 189. Library and Archives Canada, negative C 99246.

Fig. 3 Arms of the Outagamis (Meskwakis or Foxes), Outchipoues called Sauteurs (Ojibways), Pouteoutamis called Puants (Winnebago), Oumamis (Miamis) according to Louis-Armand de Lahontan, Mémoires de l’Amérique septentrionale, The Hague, 1715, following p. 189. Library and Archives Canada, negative C 99245.

To the modern reader, the one that was being ridiculous and arrogant is Lahontan himself. His view of the totemic art of the Amerindians as an inferior form of heraldry, rather than a separate emblematic form with its own logic and merits is understandable for the times but lacks the scope that ethnologic studies offer today. Though it is legitimate to compare various emblematic systems, we should not attempt to assimilate one reality to another, but rather let each have its own life and name. The recognition of this fact prompted the Canadian Heraldic Authority to give First Nation emblems a section of their own in the Public Register of Arms, Flags and Badges of Canada (fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Traditional emblem of the Hurons recorded in the name of the Huron Wendat Nation by the Chief Herald of Canada, July 31, 1992, vol. II, First Nation, p. 1. Reproduced by permission of the Canadian Heraldic Authority of Canada © Her Majesty in Right of Canada.

Although ancient warriors used crested helmets (fig. 5) and sometimes depicted images on their shields that could be blazoned in modern heraldic language, the uniquely structured coat of arms with shield, helmet and crest, that has come down to us today is the product of a specific mode of combat during a period called the Middle Ages. Its development reflects a philosophy of warfare and a vision of life with its own customs and rigorous code of conduct.

The traditional theory speculates that heraldry came into being with the invention of what we might call today a human tank: a warrior completely clad in metallic armour, bearing a protective shield and lance, installed in a saddle with good stirrups and a high front, and mounted on a strong horse protected by metal plates and coverings of boiled leather. Thus equipped such a warrior was able to strike mighty blows and to trample or crush any foot soldier in its way. But unlike modern tanks that can fire at a considerable distance, knights fought at close range, often one on one. Because their heads were enclosed in steel helmets, it became almost impossible to recognize friend from foe on the crowded and swirling battlefield. Alan Beddoe, a renowned Canadian heraldist, compared knights thus attired to tin cans without labels. The means of recognition devised evolved into an art and science called heraldry.

The traditional theory speculates that heraldry came into being with the invention of what we might call today a human tank: a warrior completely clad in metallic armour, bearing a protective shield and lance, installed in a saddle with good stirrups and a high front, and mounted on a strong horse protected by metal plates and coverings of boiled leather. Thus equipped such a warrior was able to strike mighty blows and to trample or crush any foot soldier in its way. But unlike modern tanks that can fire at a considerable distance, knights fought at close range, often one on one. Because their heads were enclosed in steel helmets, it became almost impossible to recognize friend from foe on the crowded and swirling battlefield. Alan Beddoe, a renowned Canadian heraldist, compared knights thus attired to tin cans without labels. The means of recognition devised evolved into an art and science called heraldry.

Fig. 5 A spectacular Celtic fourth century B.C. helmet with falcon crest. Iron, bronze and glass, National Museum of Romanian History.

The type of bracing used on shields probably inspired early means of recognition. Some shields may have been reinforced with one diagonal band, others with two, thus creating a saltire or St. Andrew’s cross. Others still may have used a regular cross, a chevron, or a horizontal band at the top or centre. It was also possible to brace with several bands or chevrons. A logical step beyond that was to colour these braces so that a knight could have a brace of one tincture on a shield of another tincture. An early example of this simple diversification occurred at Gisors in Normandy when troops departed for the third crusade in 1188. King Philip II of France, King Henry II of England and Count Philip of Flanders agreed on a red cross for the French, a white cross for the English and a green one for the Flemish.[5]

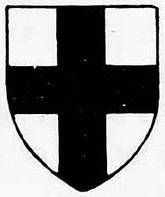

These early geometric figures, today called honourable ordinaries, provided a very poor means of distinguishing a large number of knights individually. There is little agreement among authors as to the number of honourable ordinaries. Here we have retained ten as do some authors: chief, fess, pale, bend, bend sinister, chevron, pile, pall, cross, saltire (fig. 6). These basic figures come in four colours (red, blue, black and green) and two metals (yellow and white) that can go alternately on the figure or on the field. This is subject to the restriction that an ordinary of a particular colour should go on a field of a metal and an ordinary of a metal on a field of a colour. In other words, a colour should not be placed on a colour, nor a metal on a metal. Using four colours, two metals, and ten ordinaries, this system offered only 160 possibilities, that is, 16 possibilities for each of the ten ordinaries. Moreover, should a knight be faced with 16 colour combinations of a chevron, a cross etc., trying to remember what combination belonged to what knight would not have been practical.

These early geometric figures, today called honourable ordinaries, provided a very poor means of distinguishing a large number of knights individually. There is little agreement among authors as to the number of honourable ordinaries. Here we have retained ten as do some authors: chief, fess, pale, bend, bend sinister, chevron, pile, pall, cross, saltire (fig. 6). These basic figures come in four colours (red, blue, black and green) and two metals (yellow and white) that can go alternately on the figure or on the field. This is subject to the restriction that an ordinary of a particular colour should go on a field of a metal and an ordinary of a metal on a field of a colour. In other words, a colour should not be placed on a colour, nor a metal on a metal. Using four colours, two metals, and ten ordinaries, this system offered only 160 possibilities, that is, 16 possibilities for each of the ten ordinaries. Moreover, should a knight be faced with 16 colour combinations of a chevron, a cross etc., trying to remember what combination belonged to what knight would not have been practical.

Fig. 6 The honourable ordinaries that may have originated as braces to reinforce shields.

Even while remaining within this rather closed grouping, the possibilities could be multiplied by giving the field or ordinary, or both, more than one tincture, by multiplying the same ordinary (for instance three crosses, chevrons, etc. instead of just one) or by combining the ordinaries and giving them different colours (combinations like a blue chevron between three red crosses on a white or yellow field, etc., etc.). Variations could also be introduced by drawing the edges of the ordinaries in different ways such as wavy or toothed. But even with these combinations and variances, the system remained too repetitive to function as an effective means of recognition on the battlefield. A more diversified repertoire was needed.

This diversification was achieved in many different ways, for instance, by the use of smaller geometric figures called sub-ordinaries and by displaying animals such as the lean and ferocious looking lion with tongue sticking out and huge menacing claws meant to scare the approaching enemy. The tools of warfare such as swords and spearheads, and all sorts of plants and celestial bodies appeared on the shield offering countless possibilities. Anything man-made or found in nature could be included, provided it could be stylized to have the right look. But the objective remained to create simple distinctive designs since complex shields are necessarily less effective as a means of quick recognition than simple and unique ones. This necessity to choose both content and colours judiciously made heraldry a specialized science and art form of which heralds became the specialists.

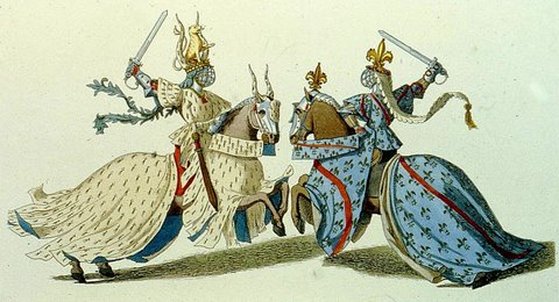

As a further means of identification, some knights fixed on top of their helmet a representation of the upper part of an animal or object made of wood or boiled leather that became known as the crest. They also attached the same crest to their horse’s heads and repeated the imagery of their shield on their surcoat (linen coats worn on top of armour), and on the coverings of their horse (fig. 7, 8). Thus both the knight and his horse, a valuable piece of property, were fully identified. Today the word crest is used colloquially to signify the entire coat of arms, although it correctly applies only to what is placed on top of the helmet. The word coat of arms (arms for short) is itself derived from the practice of displaying the content of the shield on an actual coat.

This diversification was achieved in many different ways, for instance, by the use of smaller geometric figures called sub-ordinaries and by displaying animals such as the lean and ferocious looking lion with tongue sticking out and huge menacing claws meant to scare the approaching enemy. The tools of warfare such as swords and spearheads, and all sorts of plants and celestial bodies appeared on the shield offering countless possibilities. Anything man-made or found in nature could be included, provided it could be stylized to have the right look. But the objective remained to create simple distinctive designs since complex shields are necessarily less effective as a means of quick recognition than simple and unique ones. This necessity to choose both content and colours judiciously made heraldry a specialized science and art form of which heralds became the specialists.

As a further means of identification, some knights fixed on top of their helmet a representation of the upper part of an animal or object made of wood or boiled leather that became known as the crest. They also attached the same crest to their horse’s heads and repeated the imagery of their shield on their surcoat (linen coats worn on top of armour), and on the coverings of their horse (fig. 7, 8). Thus both the knight and his horse, a valuable piece of property, were fully identified. Today the word crest is used colloquially to signify the entire coat of arms, although it correctly applies only to what is placed on top of the helmet. The word coat of arms (arms for short) is itself derived from the practice of displaying the content of the shield on an actual coat.

Fig. 7 “Chevalier Templier, XIVe Siècle” in Costumes historiques des XIIe, XIIIe, XIVe et XVe siècles …, Paris, 1861, facing p. 69, engraved by Paul Mercuri. The cross on the Templar’s shield is repeated on his surcoat and the caparison of his horse. He wears no crest on his helmet. Library and Archives Canada, negative C - 133324.

Fig. 8 A knight and horse in full regalia ready for tourneying or jousting. From Pierre Joubert, Les lys et les lions, Les Presses de l’Île-de-France, 1947.

Most of the components of a coat of arms are derived from the accoutrement of a knight. The shield, the helmet and crest were all part of the knights amour as were lambrequins believed to be derived from a cloth the knight wore on his helmet to protect from overheating under the rays of the sun. In heraldic art, lambrequins, also called mantling, took stylized forms replicating the ragged tears and tatters that would have occurred in battle (fig. 9).

Fig. 9 Components of a full coat of arms or achievement of arms. From Beddoe’s Canadian Heraldry, 1981, p. 30.

Some of the war cries became mottoes as is the case for Dieu et mon droit found in the arms of England, but most mottoes appear to be from another source, since they express moral or pious sentiments incompatible with the battlefield. In this respect we must remember that battle cries and challenges were also shouted at tournaments that were conducted in a chivalrous and courtly spirit. Some of these cries were more spiritual than aggressive, since the ladies being championed usually gave them to knights.

Every large household or fief had its battle cry, many of which contained the words “Notre-Dame”, Our Lady, such as Bourbon Nostre-Dame for the Dukes of Bourbon or Nostre-Dame au Seigneur de Coucy for the Lords of Coucy. Some were exhortations such as the Passavant li meillor, “The best goes first” of the Counts of Champagne or the elegant À la belle of the Viscount of Villenoir of Berry, a former province of central France.

Some mottoes simply refer to the name. For instance, Fortescue, which is derived from fort écu (strong shield), has for motto “Forte scutum salus ducum” meaning “A strong shield is the leader’s safeguard.” At times mottoes allude to both the name and a component in the arms such as the motto “Alte fert acquila”, “The eagle soars high” referring to the two eagle supporters of Lord Monteagle.

A number of mottoes were associated with badges that were a separate form of household identification and, in fact, preceded the armorial shield. Perhaps the most famous badge is the three ostrich feathers with the motto Ich Diene (I serve) of the Prince of Wales. The origins of the feathers can be traced back to 1329 when Philippa of Hainaut married Edward III of England. According to a legend, their son Edward Prince of Wales, also known as the Black Prince, took the motto as a sort of trophy from the arms of John the Blind, King of Bohemia, who was killed in 1346 at the battle of Crécy (France) in which the sixteen-year-old prince was a prominent commander. But this was proven unfounded.[6]

Badges often include both imagery and a motto. The famous badge of Emperor Charles V consists of two pillars, one topped with his crown as king of Spain and the other with his crown as Holy Roman Emperor, as well as a scroll around the pillars bearing the motto Plus Ultra which has a far-reaching significance. In Antiquity Gibraltar was known as the Pillars of Hercules or the Nec plus ultra meaning “nothing beyond”. Plus ultra meaning “more beyond” refers to the discovery of the Americas and the Spanish colonies established beyond the Straits of Gibraltar.[7]

The supporters, animals or humans and sometimes objects holding the shield on both sides, do not necessarily come from the battlefield. When the oblong shield was placed on the round surface of a seal, it left some unused space that engravers filled with decorative animals. Likewise badges often took the form of animals, and in some cases, these animals were lifted from the badge to act as supporters for the shield. Some authors believe that supporters grew out of the pas d’armes, a minor sort of tournament that confronted a limited number of knights having challenged one another. The participating knights were required to hang their shields from posts to be examined by challengers who would verify the opponent’s titles of nobility. These shields were guarded by squires or pageboys dressed as lions, griffins, sirens or other real or imaginary animals. The theory is that these creatures eventually found their way as guardians of the heraldic shield.[8] The compartment, usually a mound, is the support for the supporters, but it also ties together the supporters, the motto scroll, and the tip of the shield.

Like many powerful symbols, numerous aspects of the origins of heraldry remain obscure. The famous Bayeux tapestry made ca. 1077 has been considered as the proof par excellence of nascent heraldry. In a sense the tapestry only shows imagery on shields, a practice that was already fairly widespread in Antiquity. The tapestry, however, does convey a sense that the use of shields with symbols and the flying of flags as rallying marks were becoming more systematic.

Just as with other arts or sciences, heraldry evolved over a number of centuries. While the shield as a mode of identification for knights made its appearance in the second quarter of the twelfth century, crests came into existence in the thirteenth century and supporters only in the fourteenth. The first recorded heraldic shield is often attributed to Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou and Duke of Normandy. At his marriage in 1127, Henry I, his father-in-law, knighted him and hung about his neck a shield decked with gold lions. This seems to be confirmed by a funeral plaque, formerly in the cathedral of Le Mans (France) and now in that city’s museum. On it Plantagenet holds a blue shield strewn with six gold lions rampant. The authenticity of these arms has been questioned, given that the chronicler who described the marriage wrote some fifty years after the fact and because the plaque was installed some five to ten years after the Duke’s death in 1151. But if heraldry had not yet happened, it was about to do so. One of the first known armorial seals was dated 1136-38, and the first positively dated armorial seal is appended to an 1146 charter.[9] That the lions were used by Geoffrey’s descendants is unquestionable since they decorate the shield of his bastard grandson William Longespee, Earl of Salisbury, entombed in Salisbury Cathedral.[10] The hereditary nature of heraldry was to become one factor that ensured its survival.

Every large household or fief had its battle cry, many of which contained the words “Notre-Dame”, Our Lady, such as Bourbon Nostre-Dame for the Dukes of Bourbon or Nostre-Dame au Seigneur de Coucy for the Lords of Coucy. Some were exhortations such as the Passavant li meillor, “The best goes first” of the Counts of Champagne or the elegant À la belle of the Viscount of Villenoir of Berry, a former province of central France.

Some mottoes simply refer to the name. For instance, Fortescue, which is derived from fort écu (strong shield), has for motto “Forte scutum salus ducum” meaning “A strong shield is the leader’s safeguard.” At times mottoes allude to both the name and a component in the arms such as the motto “Alte fert acquila”, “The eagle soars high” referring to the two eagle supporters of Lord Monteagle.

A number of mottoes were associated with badges that were a separate form of household identification and, in fact, preceded the armorial shield. Perhaps the most famous badge is the three ostrich feathers with the motto Ich Diene (I serve) of the Prince of Wales. The origins of the feathers can be traced back to 1329 when Philippa of Hainaut married Edward III of England. According to a legend, their son Edward Prince of Wales, also known as the Black Prince, took the motto as a sort of trophy from the arms of John the Blind, King of Bohemia, who was killed in 1346 at the battle of Crécy (France) in which the sixteen-year-old prince was a prominent commander. But this was proven unfounded.[6]

Badges often include both imagery and a motto. The famous badge of Emperor Charles V consists of two pillars, one topped with his crown as king of Spain and the other with his crown as Holy Roman Emperor, as well as a scroll around the pillars bearing the motto Plus Ultra which has a far-reaching significance. In Antiquity Gibraltar was known as the Pillars of Hercules or the Nec plus ultra meaning “nothing beyond”. Plus ultra meaning “more beyond” refers to the discovery of the Americas and the Spanish colonies established beyond the Straits of Gibraltar.[7]

The supporters, animals or humans and sometimes objects holding the shield on both sides, do not necessarily come from the battlefield. When the oblong shield was placed on the round surface of a seal, it left some unused space that engravers filled with decorative animals. Likewise badges often took the form of animals, and in some cases, these animals were lifted from the badge to act as supporters for the shield. Some authors believe that supporters grew out of the pas d’armes, a minor sort of tournament that confronted a limited number of knights having challenged one another. The participating knights were required to hang their shields from posts to be examined by challengers who would verify the opponent’s titles of nobility. These shields were guarded by squires or pageboys dressed as lions, griffins, sirens or other real or imaginary animals. The theory is that these creatures eventually found their way as guardians of the heraldic shield.[8] The compartment, usually a mound, is the support for the supporters, but it also ties together the supporters, the motto scroll, and the tip of the shield.

Like many powerful symbols, numerous aspects of the origins of heraldry remain obscure. The famous Bayeux tapestry made ca. 1077 has been considered as the proof par excellence of nascent heraldry. In a sense the tapestry only shows imagery on shields, a practice that was already fairly widespread in Antiquity. The tapestry, however, does convey a sense that the use of shields with symbols and the flying of flags as rallying marks were becoming more systematic.

Just as with other arts or sciences, heraldry evolved over a number of centuries. While the shield as a mode of identification for knights made its appearance in the second quarter of the twelfth century, crests came into existence in the thirteenth century and supporters only in the fourteenth. The first recorded heraldic shield is often attributed to Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou and Duke of Normandy. At his marriage in 1127, Henry I, his father-in-law, knighted him and hung about his neck a shield decked with gold lions. This seems to be confirmed by a funeral plaque, formerly in the cathedral of Le Mans (France) and now in that city’s museum. On it Plantagenet holds a blue shield strewn with six gold lions rampant. The authenticity of these arms has been questioned, given that the chronicler who described the marriage wrote some fifty years after the fact and because the plaque was installed some five to ten years after the Duke’s death in 1151. But if heraldry had not yet happened, it was about to do so. One of the first known armorial seals was dated 1136-38, and the first positively dated armorial seal is appended to an 1146 charter.[9] That the lions were used by Geoffrey’s descendants is unquestionable since they decorate the shield of his bastard grandson William Longespee, Earl of Salisbury, entombed in Salisbury Cathedral.[10] The hereditary nature of heraldry was to become one factor that ensured its survival.

Heraldry Serving Nobility

Only a rich man could afford to be a knight. The arms, armour, horse and hay to feed the animal were far beyond the means of an ordinary man. Moreover a knight’s training began in the spring at the time of crop planting. Since knights had to have enough serfs or dependents to provide for them, they developed into a class exempt from manual work. From a closed military cast, the seigniorial class became the noble class: the military aristocracy that could be called to the battlefield at any time. The appearance of this noble class varied from one country to another. Hereditary nobility appeared in some parts of France in the early eleventh century, over a century prior to the appearance of heraldry.[11]

The extent to which the noble or military cast was select is exemplified by tournaments. Only a knight with impeccable titles of nobility could participate. The nobles who had partaken in commercial activities or married a commoner, even a respectable bourgeoise, were at first excluded. Anyone whose moral conduct was found reproachable on religious or moral grounds was left out; including knights who had neglected to protect widows and orphans or who in anyway had marred the honour of a lady. Any knight whose shield of arms was not known had to produce a number of witnesses willing to testify under oath as to his noble birth and moral qualities. During a tournament, a knight could lose his horse and all his equipment depending on the nature of the challenge. Only a wealthy man could survive as a knight after such losses.[12]

After becoming the means of identification of noble knights, coats of arms became hereditary in the second half of the twelfth century and, soon afterwards, their use spread to all classes of nobility. They became the marks of social rank, household, fief and other possessions.

Only a rich man could afford to be a knight. The arms, armour, horse and hay to feed the animal were far beyond the means of an ordinary man. Moreover a knight’s training began in the spring at the time of crop planting. Since knights had to have enough serfs or dependents to provide for them, they developed into a class exempt from manual work. From a closed military cast, the seigniorial class became the noble class: the military aristocracy that could be called to the battlefield at any time. The appearance of this noble class varied from one country to another. Hereditary nobility appeared in some parts of France in the early eleventh century, over a century prior to the appearance of heraldry.[11]

The extent to which the noble or military cast was select is exemplified by tournaments. Only a knight with impeccable titles of nobility could participate. The nobles who had partaken in commercial activities or married a commoner, even a respectable bourgeoise, were at first excluded. Anyone whose moral conduct was found reproachable on religious or moral grounds was left out; including knights who had neglected to protect widows and orphans or who in anyway had marred the honour of a lady. Any knight whose shield of arms was not known had to produce a number of witnesses willing to testify under oath as to his noble birth and moral qualities. During a tournament, a knight could lose his horse and all his equipment depending on the nature of the challenge. Only a wealthy man could survive as a knight after such losses.[12]

After becoming the means of identification of noble knights, coats of arms became hereditary in the second half of the twelfth century and, soon afterwards, their use spread to all classes of nobility. They became the marks of social rank, household, fief and other possessions.

Tournaments

It was part of a herald’s duties to announce tournaments which were in general huge colourful happenings staged to celebrate special events such as coronations. They were designed to keep knights in shape for battle and test their skills against challengers from different regions and countries. They provided entertainment for the nobility and the masses and also offered an occasion for social games and revelry. While we cannot discard the accoutrement of the knight and the battlefield as the cradle of heraldry, it seems that we have to look to the display and pageantry of tournaments to explain its blossoming into the highly decorative art that it eventually became.

In certain medieval manuscripts, such as the Armorial de la Toison d’Or (Golden Fleece), knights with all their heraldic trappings virtually look like fashion plates. This may seem fanciful, but a number of illustrations such as those found in the Tournament Book of King René d’Anjou confirm that such elaborate costumes were indeed worn (fig. 10). Some modern artistic reconstructions show knights going unto the battlefield with full heraldic dress and insignia, and it is certain that, prior to encounters on the battlefield, heraldry served as a stage for the display of the colourful pageantry of opposing forces, somewhat as in tournaments. In some depictions the dress seems little suited for practical combat. In the more realistic-looking battle scenes of the period, knights wear simpler accoutrement.[13] There was obviously a fashionable approach for show and pageantry on such occasions as tournaments and a more sober practical use of heraldic accessories on the battlefield.[14]

It was part of a herald’s duties to announce tournaments which were in general huge colourful happenings staged to celebrate special events such as coronations. They were designed to keep knights in shape for battle and test their skills against challengers from different regions and countries. They provided entertainment for the nobility and the masses and also offered an occasion for social games and revelry. While we cannot discard the accoutrement of the knight and the battlefield as the cradle of heraldry, it seems that we have to look to the display and pageantry of tournaments to explain its blossoming into the highly decorative art that it eventually became.

In certain medieval manuscripts, such as the Armorial de la Toison d’Or (Golden Fleece), knights with all their heraldic trappings virtually look like fashion plates. This may seem fanciful, but a number of illustrations such as those found in the Tournament Book of King René d’Anjou confirm that such elaborate costumes were indeed worn (fig. 10). Some modern artistic reconstructions show knights going unto the battlefield with full heraldic dress and insignia, and it is certain that, prior to encounters on the battlefield, heraldry served as a stage for the display of the colourful pageantry of opposing forces, somewhat as in tournaments. In some depictions the dress seems little suited for practical combat. In the more realistic-looking battle scenes of the period, knights wear simpler accoutrement.[13] There was obviously a fashionable approach for show and pageantry on such occasions as tournaments and a more sober practical use of heraldic accessories on the battlefield.[14]

Fig. 10 “Chefs du Tournoi XVe Siècle” from Costumes historiques des XIIe, XIIIe, XIVe et XVe siècles …, Paris, 1861, facing p. 69, engraved by Paul Mercuri. The opponents are The Duke of Brittany on the left and the Duke of Bourbon on the right. Their arms are displayed on their surcoats and the trapping of their horses. The crests on their helmets are repeated, partially or totally, on the heads of their horses. Originally from the Tournament Book of King René of Anjou-Sicily (1409-1480). Library and Archives Canada, negative C - 133327.

Perhaps the most noticeable heraldic display in a tournament city was the banners at every window where knights lodged. These banners, replicating individual shields of arms, were accompanied by the actual shield below. Another major heraldic event was the inspection of the participants’ insignia. The shields, banners and helmets with crests were exhibited in a public place, often the cloister of a monastery, and remained there for several days to be inspected by lords, ladies and heralds. If a lady had suffered any form of ill treatment from one of the knights, she presented her accusations to the judges and, if they proved founded, the knight in question was excluded from the tournament. At other times the shields were brought into the list (enclosed space for combat) by retainers to be touched by opponents with the type of lance, sharp or blunt, that would serve in battle.[15] Individual combatants could challenge one another and the terms of these confrontations were placed in the hands of heralds.

Since it was the duty of heralds to ensure that knights were who they claimed to be and worthy participants, they were required to record accurately the composition of armorial shields and ensure that there were no duplicates. To this end they devised a vocabulary based on the language used at the time, in the trades for instance. But as spoken language evolved, many heraldic words became archaic and were only understood by specialists, as is the case today. The persistent idea that the language of blazonry was acquired during the crusades has been disproved by modern studies.[16]

Since it was the duty of heralds to ensure that knights were who they claimed to be and worthy participants, they were required to record accurately the composition of armorial shields and ensure that there were no duplicates. To this end they devised a vocabulary based on the language used at the time, in the trades for instance. But as spoken language evolved, many heraldic words became archaic and were only understood by specialists, as is the case today. The persistent idea that the language of blazonry was acquired during the crusades has been disproved by modern studies.[16]

The Battlefield

Doubts were raised as to the efficiency of the painted shield as a means of individual identification on the battlefield. Early heraldic designs tended to be repetitive. Even into the thirteenth century, so many knights displayed variously coloured lions that efficient identification was almost impossible. Moreover the shorter flat shields that came into use in the twelfth century could only be distinguished if viewed from the front within an angle of less than 180o. Thus a knight approaching at right angle from the side would only have seen one edge of the other knight’s shield and not much of his heraldic signature on the surface.

During the first charge between opposing armies, even though the troops were not arranged in well-arrayed formation, the enemy was easily recognized as the one rushing forward from the opposite direction. It was in the group combat, or the mêlée, that followed where problems of recognition could arise. This manner of fighting involved circular or churning movements of horses with iron shoes that raised mud when the ground was wet and dust when it was dry. A muddy shield is hard to distinguish particularly if a few well-applied blows also mar the surface. That the mêlée could raise clouds of dust is well recorded. Of the 60 knights and squires who perished at the Nuys tournament near Cologne in 1240, the majority was said to have been choked by excessive dust in the air.[17] During the battle of Bouvines fought in Flanders in the summer of 1214, the dust rose so thickly that the assailants could hardly see one another. Dust in the air makes for poor visibility, as anyone who has trailed another car on a dry dirt road will know.

Man-to-man combat was popularized by the joust which is one of the most spectacular aspects of tournaments. Certainly one-on-one combat occurred on the battlefield, but there can be little doubt that fighting as a group was more effective, and the recognition of individual shields would not have been so important in this type of confrontation. A recurring theme is the rally under the banner and war cry of a duke, earl, baron or knight banneret (knight leading troops under his banner) to charge as a close-knit unit. The Chronicles of the medieval French Chronicler and poet Jean Froissart contain a good description of such a means of rallying at the battle of Otterburn:

“Then the earl James Douglas, who was young and strong and of great desire to get praise and grace, and was willing to deserve to have it, and cared for no pain nor travail, came forth with his banner and cried, ‘Douglas, Douglas!’ and sir Henry Percy and sir Ralph his brother, who had great indignation against the earl Douglas because he had won the pennon of their arms at the barriers before Newcastle, came to that part and cried, ‘Percy!’ Their two banners met and their men: there was a sore fight: the Englishmen were so strong and fought so valiantly that they reculed the Scots back.”[18]

The force of the united charge is exemplified by another tragic event. At the battle of Crécy, John the Blind of Bohemia who fought with the French asked his men to lead him far into enemy lines in order that he might at least strike a blow at his foes. The knights tied the reins of their horses together in order to move as one solid unit and keep the king with them. Thus they penetrated so far into enemy lines that they were surrounded and all killed except two. The next morning their dead horses were found still tied together.[19]

In modern warfare we frequently speak of friendly fire in cases when one’s own or allied troops are mistakenly attacked. Friendly attacks also occurred in the Middle Ages. During a battle of the Wars of the Roses fought at Barnet in 1471, the troops of Edward IV bore as a badge a white rose placed upon a sun representing the House of York. In the morning mist, the Earl of Warwick mistook the white star of his ally De Vere Earl of Oxford for the white rose of York and proceeded to attack his own supporters.[20]

Here badges that frequently appear on battle flags such as guidons identified the two groups of men. Although misidentification occurred in this case because the two marks were quite similar, it does raise the question as to the practical use of individual identification. Group identification with the one shield of the lord is found a number of times in medieval records such as Jean Froissart’s Chronicles. It seems, in fact, quite obvious that identifying a group of knights with a single clear distinctive mark would have been the more efficient means of fighting as a unit and even man to man. With one clear mark, it would have been easier to recognize both groups and individuals as friends or foes. But it would not have allowed recognition of a knight as a particular person with a specific name, and this was viewed as important for reasons obviously other than efficiency.

Heraldry on the battlefield may have served more to enhance one’s sense of pride and honour than for recognition as an individual knight, but it seems important to look at other possibilities. Since heraldry was obviously present on the battlefield, it may have worked in a way that today is not fully understood. It is doubtful that the knight could recognize the shields of all his enemies, but he only needed to be familiar with those of his friends fighting closely by his side, anything else becoming a foe. Knight underwent years of training, and what a trained person can do often seems virtually impossible to others, particularly if exposed to these realities from written accounts. The power of heraldic imagery cannot be discounted since it can be recognized at a glance even on a modern fast moving vehicle or on a partially visible flag when little wind is blowing.

In the eleventh century, improvements to armour made the short bow and the hand-thrown javelin almost useless. The mounted knight then became the most important force on the battlefield and man-to-man combat more widespread. Footmen lost almost all importance. In these heydays of knighthood, chivalry and honour dominated the field of war. Though knights did die both on the battlefield and during tournaments, the idea of a noble sport still prevailed because courage was the supreme virtue. Heralds played a role in the choice of battlegrounds that were flat without any natural obstacles and agreeable to both parties.[21] Every effort seemed to have been made to choose both the day and place that would provide the optimum conditions for the exhibition of chivalric prowess at its best. This likely included attempting to predict the weather by the means available then so that wet muddy fields could be avoided.

If heraldry was prominently displayed at tournaments where mud would fly and clouds of dust shroud the combatants, why could it not serve as well on the field of war? Excessive mud and dust surely represented extreme conditions. Dust and mud cannot exist at the same time, and there must have been an ideal middle ground. Combat on dry grassy land such as pasture would no doubt have caused grassy clumps to fly, but would surely not have raised that much dust or mud. Driving a car in good light on a dry highway can be exhilarating, but a car in freezing or pouring rain, extreme fog, a snowstorm or really slow moving traffic is not efficient at all. Still a car is generally considered a relatively efficient machine.

There is little doubt that heraldry fostered recognition on the battlefield under some circumstances, but distinguishing shields may have been easier for someone not engaged in the battle itself. Heralds played a role as military advisers where the recognition of individual shields was required. Posted not far from their lord’s banner, they followed the military engagements by closely looking at the shields of opposing knights, a bit like a coach recognizing numbers at a hockey game. Since they recognized each knight by his shield, they could report the prowess of some or the cowardice of others. Here the individual shield took on the meaning of individual performance, honour and courage, which was important for individual knights.[22]

The individualized shield as an instrument of recognition may have served well in specific circumstances and not so well in others. Since warriors in armour on horses and bearing a decorated shield already existed in Antiquity, it was perhaps not so much the type of armour as the philosophy of warfare as a stage for individual bravery and skill that produced the spark bringing heraldry into existence. For a time tournaments and battlefields were almost mirror images of one another. This unique situation in history with its sportive mentality, though not devoid of brutality, appears to have been a favourable breeding ground for the development of heraldry into the systematic art and science that it became.

Doubts were raised as to the efficiency of the painted shield as a means of individual identification on the battlefield. Early heraldic designs tended to be repetitive. Even into the thirteenth century, so many knights displayed variously coloured lions that efficient identification was almost impossible. Moreover the shorter flat shields that came into use in the twelfth century could only be distinguished if viewed from the front within an angle of less than 180o. Thus a knight approaching at right angle from the side would only have seen one edge of the other knight’s shield and not much of his heraldic signature on the surface.

During the first charge between opposing armies, even though the troops were not arranged in well-arrayed formation, the enemy was easily recognized as the one rushing forward from the opposite direction. It was in the group combat, or the mêlée, that followed where problems of recognition could arise. This manner of fighting involved circular or churning movements of horses with iron shoes that raised mud when the ground was wet and dust when it was dry. A muddy shield is hard to distinguish particularly if a few well-applied blows also mar the surface. That the mêlée could raise clouds of dust is well recorded. Of the 60 knights and squires who perished at the Nuys tournament near Cologne in 1240, the majority was said to have been choked by excessive dust in the air.[17] During the battle of Bouvines fought in Flanders in the summer of 1214, the dust rose so thickly that the assailants could hardly see one another. Dust in the air makes for poor visibility, as anyone who has trailed another car on a dry dirt road will know.

Man-to-man combat was popularized by the joust which is one of the most spectacular aspects of tournaments. Certainly one-on-one combat occurred on the battlefield, but there can be little doubt that fighting as a group was more effective, and the recognition of individual shields would not have been so important in this type of confrontation. A recurring theme is the rally under the banner and war cry of a duke, earl, baron or knight banneret (knight leading troops under his banner) to charge as a close-knit unit. The Chronicles of the medieval French Chronicler and poet Jean Froissart contain a good description of such a means of rallying at the battle of Otterburn:

“Then the earl James Douglas, who was young and strong and of great desire to get praise and grace, and was willing to deserve to have it, and cared for no pain nor travail, came forth with his banner and cried, ‘Douglas, Douglas!’ and sir Henry Percy and sir Ralph his brother, who had great indignation against the earl Douglas because he had won the pennon of their arms at the barriers before Newcastle, came to that part and cried, ‘Percy!’ Their two banners met and their men: there was a sore fight: the Englishmen were so strong and fought so valiantly that they reculed the Scots back.”[18]

The force of the united charge is exemplified by another tragic event. At the battle of Crécy, John the Blind of Bohemia who fought with the French asked his men to lead him far into enemy lines in order that he might at least strike a blow at his foes. The knights tied the reins of their horses together in order to move as one solid unit and keep the king with them. Thus they penetrated so far into enemy lines that they were surrounded and all killed except two. The next morning their dead horses were found still tied together.[19]

In modern warfare we frequently speak of friendly fire in cases when one’s own or allied troops are mistakenly attacked. Friendly attacks also occurred in the Middle Ages. During a battle of the Wars of the Roses fought at Barnet in 1471, the troops of Edward IV bore as a badge a white rose placed upon a sun representing the House of York. In the morning mist, the Earl of Warwick mistook the white star of his ally De Vere Earl of Oxford for the white rose of York and proceeded to attack his own supporters.[20]

Here badges that frequently appear on battle flags such as guidons identified the two groups of men. Although misidentification occurred in this case because the two marks were quite similar, it does raise the question as to the practical use of individual identification. Group identification with the one shield of the lord is found a number of times in medieval records such as Jean Froissart’s Chronicles. It seems, in fact, quite obvious that identifying a group of knights with a single clear distinctive mark would have been the more efficient means of fighting as a unit and even man to man. With one clear mark, it would have been easier to recognize both groups and individuals as friends or foes. But it would not have allowed recognition of a knight as a particular person with a specific name, and this was viewed as important for reasons obviously other than efficiency.

Heraldry on the battlefield may have served more to enhance one’s sense of pride and honour than for recognition as an individual knight, but it seems important to look at other possibilities. Since heraldry was obviously present on the battlefield, it may have worked in a way that today is not fully understood. It is doubtful that the knight could recognize the shields of all his enemies, but he only needed to be familiar with those of his friends fighting closely by his side, anything else becoming a foe. Knight underwent years of training, and what a trained person can do often seems virtually impossible to others, particularly if exposed to these realities from written accounts. The power of heraldic imagery cannot be discounted since it can be recognized at a glance even on a modern fast moving vehicle or on a partially visible flag when little wind is blowing.

In the eleventh century, improvements to armour made the short bow and the hand-thrown javelin almost useless. The mounted knight then became the most important force on the battlefield and man-to-man combat more widespread. Footmen lost almost all importance. In these heydays of knighthood, chivalry and honour dominated the field of war. Though knights did die both on the battlefield and during tournaments, the idea of a noble sport still prevailed because courage was the supreme virtue. Heralds played a role in the choice of battlegrounds that were flat without any natural obstacles and agreeable to both parties.[21] Every effort seemed to have been made to choose both the day and place that would provide the optimum conditions for the exhibition of chivalric prowess at its best. This likely included attempting to predict the weather by the means available then so that wet muddy fields could be avoided.

If heraldry was prominently displayed at tournaments where mud would fly and clouds of dust shroud the combatants, why could it not serve as well on the field of war? Excessive mud and dust surely represented extreme conditions. Dust and mud cannot exist at the same time, and there must have been an ideal middle ground. Combat on dry grassy land such as pasture would no doubt have caused grassy clumps to fly, but would surely not have raised that much dust or mud. Driving a car in good light on a dry highway can be exhilarating, but a car in freezing or pouring rain, extreme fog, a snowstorm or really slow moving traffic is not efficient at all. Still a car is generally considered a relatively efficient machine.

There is little doubt that heraldry fostered recognition on the battlefield under some circumstances, but distinguishing shields may have been easier for someone not engaged in the battle itself. Heralds played a role as military advisers where the recognition of individual shields was required. Posted not far from their lord’s banner, they followed the military engagements by closely looking at the shields of opposing knights, a bit like a coach recognizing numbers at a hockey game. Since they recognized each knight by his shield, they could report the prowess of some or the cowardice of others. Here the individual shield took on the meaning of individual performance, honour and courage, which was important for individual knights.[22]

The individualized shield as an instrument of recognition may have served well in specific circumstances and not so well in others. Since warriors in armour on horses and bearing a decorated shield already existed in Antiquity, it was perhaps not so much the type of armour as the philosophy of warfare as a stage for individual bravery and skill that produced the spark bringing heraldry into existence. For a time tournaments and battlefields were almost mirror images of one another. This unique situation in history with its sportive mentality, though not devoid of brutality, appears to have been a favourable breeding ground for the development of heraldry into the systematic art and science that it became.

Leaving the Battlefield

The eventual disappearance of heraldry from the battlefield is partly explained by the decline of the mounted knight in armour as the absolute force in medieval warfare. This would come with the introduction of the longbow, the increased use of crossbows capable of piercing amour and the rise in importance of footmen as a force that could stop the charge of the cavalry. There was also a change in mentality. Fighting was no longer a question of individual prowess and honour without trickery but a concerted effort to win as an army by making maximum use of strategy and ambush if possible. This new approach would at the same time greatly challenge the notion of chivalry on the battlefield.

At the battle of Hastings (1066), the English troops fighting on foot were defeated only when they abandoned their entrenched position behind their wall of shields to give chase to the Normans retreating or feigning retreat. A defensive approach would later become one of the great strengths of the English army. Both the battles of Crécy (1346) and Poitiers (1356) were won by disciplined English troops who, though vastly inferior in number, fortified their position, awaited the enemy, and made good use of their archers.

Actually the English had learned a new way to make war while fighting the Scots at the battles of Bannockburn (1314), of Dupplin Moor (1332), and of Halidon Hill (1333). At Bannockburn the charge of English cavalry was halted by a much smaller Scottish force of compact footmen equipped with 12-foot spears. In the two other battles, a shower of arrows from longbows had carried the day for the English.[23]

From these three battles, the English developed a strategic approach that depended on an advantageous choice of ground, preferably a higher ground with hedges and bushes to which they could add palisades and trenches. They realized the importance of a preponderance of archers firing from the flanks that needed to be protected from cavalry attack by natural obstacles or infantry. They had become aware that dismounted men in armour, knights or footmen, were the way to stop the onslaught of the cavalry. They had also seen the value of a cavalry reserve being kept close by so that mounted action was possible if required.

When the French met the English at Crécy, they were confident that their cavalry of mounted knights would crush the enemy. It was the same faith in the cavalry that the English had entertained at the battle of Bannockburn. With few exceptions until then, medieval battles had been won by an overwhelming and decisive charge of mounted knights. The French continued to rely too heavily on superior numbers and their cavalry. They adhered to a code of courage and honour with little strategy, cunning or discipline. The line of command was not always clear and they had a tendency to charge brashly against lethal obstacles. At Crécy for instance, Philippe IV of France was unable to prevent a precipitous and ill concerted attack by his mounted knights.[24]

An example which showed the disregard of foot soldiers and too great a reliance on the might of the cavalry also occurred at the battle of the Golden Spur in 1302, which opposed French troops to a rebellious Flemish army. The Flemish lines had strategically positioned themselves between the numerous ditches and streams that crossed the field, and made it difficult for the French cavalry to reach them. A large contingent of French infantry led the initial attack with considerable success. Not wanting footmen to have the honour of victory, the French commander, Count Robert II of Artois, recalled them and allowed the cavalry to charge precipitously in order to claim the victory. Impeded by the terrain and their own infantry, the French cavalry were an easy prey for the heavily-armed Flemish infantry. It was not unusual for knights to trample footmen whether ally or foe if they impeded the cavalry’s charge.

The contempt of mounted knights for other types of forces was again apparent at the battle of Crécy where French knights trampled their own Genoese crossbowmen because they impeded their assault. During this encounter the young Black Prince was able to repulse the charge of Philippe VI’s French cavalry by having his knights dismount and fight as infantry with the butts of their lances steadied in the ground.[25] A similar infantry dismounted manoeuvre attempted by the French at Poitiers in 1456 failed when English archers hidden in thickets on both sides of their path sent lethal missiles raining upon them.[26] The example of Crécy should have alerted the French to the possibility of routing the cavalry by men in armour on foot supported by archers, but France was slow to adopt this mode of fighting.

The same reliance on numbers, including a large cavalry, rather than sound tactics lost the day at Agincourt in 1415. While the French assembled on a muddy ploughed field, the English positioned themselves in a narrower space between two forests that protected their flanks and created a bottleneck for the advancing French troops. The French cavalry charged first and was met with a shower of arrows from English longbows wounding both men and horses. The few knights who reached the archers were impaled on stakes planted at an angle in the ground. Then the English infantry was able to neutralize the onslaught of the French infantry rushing towards them on extremely muddy grounds by staying in place in their advantageous position.[27]

While the wasting of the French cavalry could to a large extent be attributed to the arrogance and sense of superiority of mounted knights, they were victims of the evolution of medieval engagement. As armies sought grounds that offered the best advantages and attacked when it best suited them, mounted knights with their code of conduct and honour no longer reigned supreme on the battlefield.

The defeat of armies of mounted knights in Flanders, France and at Morgarten in Switzerland also spelled the beginning of the end for the heraldic shield on the battlefield. Partly in response to the might of the longbow, steel plated armour was greatly improved to offer protection from head to foot. The surcoat was dropped to show the full beauty of better and more elaborate armour. These improvements made the shield less useful and it gradually disappeared from the battlefield to be used only at tournaments. France finally recognized the importance of archers, and made impressive provisions for their training and maintenance in 1448, but on the eve when gunpowder was becoming a force on the battlefield. The appearance of firearms in war caused the gradual disappearance of the now useless traditional armour, including the heraldic shield. It is interesting that modern forces have retained the flags and badges that were once used by knights.

In 1429, under the impetus of a humble nineteen year old maid called Joan of Arc who claimed to operate under the guidance of God allied with a number of competent commanders, France began re-conquering its lands from the English. But contrary to a popular belief, Joan of Arc did not boot the English out of France. She demonstrated that the English army was not invincible and probably gave Charles VII the confidence and sense of purpose he previously lacked to succeed in this formidable undertaking. By 1453 the only English possession remaining in France was Calais.

The eventual disappearance of heraldry from the battlefield is partly explained by the decline of the mounted knight in armour as the absolute force in medieval warfare. This would come with the introduction of the longbow, the increased use of crossbows capable of piercing amour and the rise in importance of footmen as a force that could stop the charge of the cavalry. There was also a change in mentality. Fighting was no longer a question of individual prowess and honour without trickery but a concerted effort to win as an army by making maximum use of strategy and ambush if possible. This new approach would at the same time greatly challenge the notion of chivalry on the battlefield.

At the battle of Hastings (1066), the English troops fighting on foot were defeated only when they abandoned their entrenched position behind their wall of shields to give chase to the Normans retreating or feigning retreat. A defensive approach would later become one of the great strengths of the English army. Both the battles of Crécy (1346) and Poitiers (1356) were won by disciplined English troops who, though vastly inferior in number, fortified their position, awaited the enemy, and made good use of their archers.

Actually the English had learned a new way to make war while fighting the Scots at the battles of Bannockburn (1314), of Dupplin Moor (1332), and of Halidon Hill (1333). At Bannockburn the charge of English cavalry was halted by a much smaller Scottish force of compact footmen equipped with 12-foot spears. In the two other battles, a shower of arrows from longbows had carried the day for the English.[23]

From these three battles, the English developed a strategic approach that depended on an advantageous choice of ground, preferably a higher ground with hedges and bushes to which they could add palisades and trenches. They realized the importance of a preponderance of archers firing from the flanks that needed to be protected from cavalry attack by natural obstacles or infantry. They had become aware that dismounted men in armour, knights or footmen, were the way to stop the onslaught of the cavalry. They had also seen the value of a cavalry reserve being kept close by so that mounted action was possible if required.

When the French met the English at Crécy, they were confident that their cavalry of mounted knights would crush the enemy. It was the same faith in the cavalry that the English had entertained at the battle of Bannockburn. With few exceptions until then, medieval battles had been won by an overwhelming and decisive charge of mounted knights. The French continued to rely too heavily on superior numbers and their cavalry. They adhered to a code of courage and honour with little strategy, cunning or discipline. The line of command was not always clear and they had a tendency to charge brashly against lethal obstacles. At Crécy for instance, Philippe IV of France was unable to prevent a precipitous and ill concerted attack by his mounted knights.[24]

An example which showed the disregard of foot soldiers and too great a reliance on the might of the cavalry also occurred at the battle of the Golden Spur in 1302, which opposed French troops to a rebellious Flemish army. The Flemish lines had strategically positioned themselves between the numerous ditches and streams that crossed the field, and made it difficult for the French cavalry to reach them. A large contingent of French infantry led the initial attack with considerable success. Not wanting footmen to have the honour of victory, the French commander, Count Robert II of Artois, recalled them and allowed the cavalry to charge precipitously in order to claim the victory. Impeded by the terrain and their own infantry, the French cavalry were an easy prey for the heavily-armed Flemish infantry. It was not unusual for knights to trample footmen whether ally or foe if they impeded the cavalry’s charge.

The contempt of mounted knights for other types of forces was again apparent at the battle of Crécy where French knights trampled their own Genoese crossbowmen because they impeded their assault. During this encounter the young Black Prince was able to repulse the charge of Philippe VI’s French cavalry by having his knights dismount and fight as infantry with the butts of their lances steadied in the ground.[25] A similar infantry dismounted manoeuvre attempted by the French at Poitiers in 1456 failed when English archers hidden in thickets on both sides of their path sent lethal missiles raining upon them.[26] The example of Crécy should have alerted the French to the possibility of routing the cavalry by men in armour on foot supported by archers, but France was slow to adopt this mode of fighting.

The same reliance on numbers, including a large cavalry, rather than sound tactics lost the day at Agincourt in 1415. While the French assembled on a muddy ploughed field, the English positioned themselves in a narrower space between two forests that protected their flanks and created a bottleneck for the advancing French troops. The French cavalry charged first and was met with a shower of arrows from English longbows wounding both men and horses. The few knights who reached the archers were impaled on stakes planted at an angle in the ground. Then the English infantry was able to neutralize the onslaught of the French infantry rushing towards them on extremely muddy grounds by staying in place in their advantageous position.[27]

While the wasting of the French cavalry could to a large extent be attributed to the arrogance and sense of superiority of mounted knights, they were victims of the evolution of medieval engagement. As armies sought grounds that offered the best advantages and attacked when it best suited them, mounted knights with their code of conduct and honour no longer reigned supreme on the battlefield.

The defeat of armies of mounted knights in Flanders, France and at Morgarten in Switzerland also spelled the beginning of the end for the heraldic shield on the battlefield. Partly in response to the might of the longbow, steel plated armour was greatly improved to offer protection from head to foot. The surcoat was dropped to show the full beauty of better and more elaborate armour. These improvements made the shield less useful and it gradually disappeared from the battlefield to be used only at tournaments. France finally recognized the importance of archers, and made impressive provisions for their training and maintenance in 1448, but on the eve when gunpowder was becoming a force on the battlefield. The appearance of firearms in war caused the gradual disappearance of the now useless traditional armour, including the heraldic shield. It is interesting that modern forces have retained the flags and badges that were once used by knights.

In 1429, under the impetus of a humble nineteen year old maid called Joan of Arc who claimed to operate under the guidance of God allied with a number of competent commanders, France began re-conquering its lands from the English. But contrary to a popular belief, Joan of Arc did not boot the English out of France. She demonstrated that the English army was not invincible and probably gave Charles VII the confidence and sense of purpose he previously lacked to succeed in this formidable undertaking. By 1453 the only English possession remaining in France was Calais.

Fig. 11 Decorative plate showing Joan of Arc in the armour paid by King Charles VII, on a white horse given her by the Duke of Alençon, commander of the army. She holds a staff flying her swallow-tailed standard: a white field strewn with gold fleurs-de-lis, the inscription “Jhesus Maria” and Christ depicted with angels. “En avant!” was part of her war cry. Her arms on the rim are a blue field with a silver sword pointing upwards, hilt and pommel gold, between two fleurs-de- lis and a crown above, all gold. Both her standard and arms have given rise to various interpretations, see: http://www.stjoan-center.com/j-cc/ and http://www.blason-armoiries.org/heraldique/j/jeanne-d-arc.htm. The majolica plate is attributed to the Choisy le Roi pottery in France and dated end of the nineteenth century. Belongs to A. & P. Vachon.

The defeat of the Yorkists at the battle of Bosworth Field in 1485 brought an end to the War of the Roses in England. King Henry VII established a new form of government that derived its strength from Parliament and the merchant class. In France Louis XI, often called the Bourgeois King, managed to keep in check the large feudal houses that had caused a great deal of division. He strove to promote industry and commerce even at the expense of the old feudal order, but unlike England, all in favour of absolute power for the king. Though remnants of feudal society survived in certain institutions such as the noble class and the seigniorial system, feudalism ceased to be a mode of government in both England and France.

Dawning was the age of Cervantes’ Don Quixote where the ideals of chivalry would survive only in the obsessed mind of an old and doting romantic. However heraldry remained a major legacy from the Middle Ages. Like some other medieval manifestations, it survived because it remained useful and could be adapted to several purposes. Like the phoenix, it perpetually renewed itself.

Dawning was the age of Cervantes’ Don Quixote where the ideals of chivalry would survive only in the obsessed mind of an old and doting romantic. However heraldry remained a major legacy from the Middle Ages. Like some other medieval manifestations, it survived because it remained useful and could be adapted to several purposes. Like the phoenix, it perpetually renewed itself.

Survival off the Battlefield

The survival of heraldry was assured long before it left the battlefield. After becoming hereditary emblems used by all classes of nobility including the use of their father’s or husband’s arms by women, coats of arms spread to all classes of society and to all types of institutions.

The rapid spread of non-military heraldry throughout Europe is explained partly by what has been termed the Twelfth Century Renaissance, which began at the end of the eleventh century, and whose effects lasted into the thirteenth century. Progress in architectural, intellectual, artistic, social, and religious fields was considerable. Agriculture and commerce flourished, more money circulated, cities were revitalized and new ones created. Besides the noble class, there arose a new class with money and property commonly known as the bourgeoisie.