MYSTERY FLAGS ON A RENAISSANCE MAP

Auguste Vachon, Outaouais Herald Emeritus

Originally published in Gonfanon (Newsletter of the Royal Heraldry Society of Canada), Winter 2011, p. 15-16.

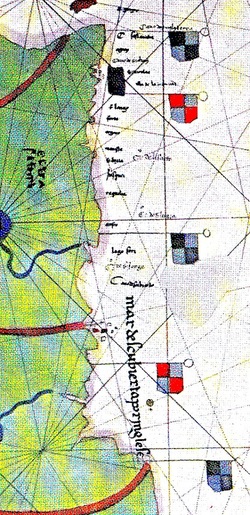

A world map by Juan de la Cosa dated 1500 shows the Atlantic Coast of North America, and beside it, five flags which have long been, and still are described as English flags, banners or standards, to the point that this assertion is found in John Cabot’s biography in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Though there are reasons to believe that some flags could represent England, a closer examination of the whole map reveals that at least three of them are more likely to belong to another geographical entity. Of the five flags, three are quarterly Argent and Sable (quartered white and black) and are separated by two others quarterly Argent and Gules (quartered white and red). Because these flags do not correspond to English ones, and are not those of any other country having explored the continent at the time, some authors have viewed them as fanciful or purely decorative, but again this does not seem to be the right interpretation.

A world map by Juan de la Cosa dated 1500 shows the Atlantic Coast of North America, and beside it, five flags which have long been, and still are described as English flags, banners or standards, to the point that this assertion is found in John Cabot’s biography in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Though there are reasons to believe that some flags could represent England, a closer examination of the whole map reveals that at least three of them are more likely to belong to another geographical entity. Of the five flags, three are quarterly Argent and Sable (quartered white and black) and are separated by two others quarterly Argent and Gules (quartered white and red). Because these flags do not correspond to English ones, and are not those of any other country having explored the continent at the time, some authors have viewed them as fanciful or purely decorative, but again this does not seem to be the right interpretation.

Detail from a copy of de la Cosa’s map showing the five flags. The original map is in the Museo Naval, Madrid.

Juan de la Cosa (c. 1460-1509) was a Spanish cartographer, conquistador and explorer. He sailed with Christopher Columbus on his first three voyages, and was the owner and captain of the Santa Maria. In 1499, he was first pilot for the expedition of Alonso de Ojeda and Amerigo Vespucci, and along with them, was the first European to set foot on the South American mainland.

His world map includes the territories of the Americas discovered in the 15th century. The original parchment measures 93 x 183 cm and the map is depicted in ink and water colours. It was found in 1832 in a Paris shop by Baron Walckenaer, a bibliophile and Dutch Ambassador to France. Its authenticity was verified by a famous German scholar, Alexander Humboldt. Upon the death of Baron Walckenaer in 1853, the map was purchased by Queen Isabella II of Spain, and though greatly deteriorated, is now a treasure of the Museo Naval in Madrid.

The configuration of the land and its positioning is more or less exact depending on the regions. The date of the map has been a question of some controversy, but it is actually dated under a vignette, at the level of Honduras, depicting Saint Christopher carrying baby Jesus across water: “Juan de la Cosa la fizo en el puerto de S. mª. en el año de 1500” (Juan de la Cosa made it in the port of Santa Maria in the year 1500). Santa Maria is a small port at the mouth of the Guadalquivir River near Cadiz (Macias, p. 3: for this reference and subsequent ones, see the full entry in the bibliography).

Why were the flags along the Atlantic coast identified as English? One reason is the inscription “Mar descubierta por inglese[s]” (Sea discovered by the English) near the two southernmost flags and “Cavo de Ynglaterra” (Cape of England) just above the northernmost one, which is believed to mark the point of John Cabot’s landfall in 1497. Although the geographical location corresponding to the positioning of the latter inscription has given rise to much speculation, there is no way of pinpointing a precise place on this map because of the lack of precision in that particular region. Still, the flags could be viewed as English by a process of elimination.

First let as look at the possibility that they could be Portuguese. We know that João Fernandes reached Greenland in 1499, which he named “Terra de Labrador” (land of the ploughman, or landowner). The fact that this name would later be applied to Labrador as we know it today indicates how fluid the knowledge of geographical locations was at the time. Only a year later, Gaspar Corte-Real likely reached the coast of Newfoundland (Hayes, p. 20-21, 24). But the flags representing Portugal on early maps usually are Azure five plates in saltire and a bordure Gules (five white roundels arranged in saltire on a blue field within a red border). The same flag also appears without a bordure. At times, the plates are not visible, and all that can be distinguished is a field and the bordure. Examples of these Portuguese flags can be seen on Pedro Reinel’s map of 1504 (Hayes, p. 22), and on a detail of Alberto Cantino’s planisphere of 1502 showing Portuguese mining and trading interests on the Gold Coast of Africa, in the vicinity of Sierra Leone and St. George Castle at Elmina (Dor-Ner, p. 73).

De la Cosa, for his own part, represented Portugal with a variety of flags. Off the coast of Africa, we see three Portuguese caravels. Two fly a white flag with a red bordure and another, nearer the coast, flaunts a pointed green or blue flag bearing a white square with five besants (yellow roundels) in saltire. On the Gold Coast, the banners appear white with a blue bordure while, in the area of Morocco where the Portuguese had expanded, we see a white field with a gold bordure. For the island of Madeira and the Azores, it is now a red field with a gold bordure (as seen on de la Cosa’s map in Marcias, p. 21 and Hayes, p. 19). The variety of colours may be inconsistencies on the part of the creator or may be the result of retouches or chemical reactions that modified the pigments over the years. The fact that I am working from a photographic reproduction should also be taken into account. In any case, because all flags representing Portugal on de la Cosa’s map, except one naval flag, have the characteristic bordure, we can be reasonably sure that the five flags along the North Atlantic coast are not Portuguese.

The quarterly Argent and Sable flags are present elsewhere on the map, namely one above Iceland and another above Scandinavia, which at least opens up a serious possibility that they represent Norse territories and explorations. It should not be particularly surprising to find the same flags along the north Atlantic coast since, at the time, Greenland, which was discovered and settled by the Norse, was viewed as being part of the North American continent, not as an island (Hayes, p. 24). As Skelton points out (see bibliography), the North Atlantic coastline on de la Cosa’s map “has been variously held to represent the north shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence; the south coast of Newfoundland; the east coasts of Newfoundland and Labrador; Nova Scotia and Newfoundland; or even the west coast of Greenland.”

Unlike the other three flags, the two quarterly Argent and Gules ones are found only along the North Atlantic coast. If they had appeared elsewhere on the map, a more assured identification might have been possible, but this is not the case. Still, by the simple process of eliminating other possible countries and the presence nearby of inscriptions referring to England or the English, the two flags are likely meant to represent England. The alternation of the two types of flags seems to confirm that the cartographer, who probably worked from an indirect account of Cabot’s voyages (Macias, p. 23), saw the coast of Greenland and the coast of North America that Cabot had discovered as being within the same general area.

We note that, further south, de la Cosa replicates many examples of the Spanish flag of Castile and Leon as it existed at the time. Why did he not do the same for Scandinavia and England, if indeed the flags were meant to represent these countries? It must be kept in mind that the notion of national flag was not, at that time, as well established as it is today. The Kalmar Union (1397–1523) that united Denmark, Norway and Sweden under a single monarch was identified by a gold flag with a red cross, but de la Cosa, working in Santa Maria in 1500, may not have known this. The same situation may also have existed for the flags that identified England or the English sovereign at the time. Within the same time period, cartographers identified England with the red cross of St. George on a white shield, for instance on the aforementioned Cantino’s planisphere of 1502 and Reinel’s map of 1504 (Hayes, p. 21-22), but de la Cosa may not have been aware of this as it was a recent and, as it seems, a passing development in cartography.

The reinterpretation of de la Cosa’s five North Atlantic flags as being three Norse and two English, and a Norse flag occupying the southernmost position, is of considerable importance in supporting a northerly latitude for Cabot’s point of landing.

Note: De la Cosa’s entire map can be found at several sites on the Internet. There is also a good reproduction with a detail of the Atlantic Coast in Hayes, p. 18-19.

Bibliography

Dor-Ner, Zvi. Columbus and the Age of Discovery. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1991.

Hayes, Derek. Historical Atlas of Canada. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2002.

Macias, Luis A. Robles. “Juan de la Cosa’s Projection: A Fresh Analysis of the Earliest Preserved Map of the Americas,” 24 May 2010, consulted Jan. 2, 2012 at: http://www.stonybrook.edu/libmap/coordinates/seriesa/no9/a9.pdf.

Skelton, R. A. “John (Giovanni) Cabot (Caboto)” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, consulted Jan. 2, 2012 at: http://www.biographi.ca/009004-119.01-e.php?&id_nbr=101.

His world map includes the territories of the Americas discovered in the 15th century. The original parchment measures 93 x 183 cm and the map is depicted in ink and water colours. It was found in 1832 in a Paris shop by Baron Walckenaer, a bibliophile and Dutch Ambassador to France. Its authenticity was verified by a famous German scholar, Alexander Humboldt. Upon the death of Baron Walckenaer in 1853, the map was purchased by Queen Isabella II of Spain, and though greatly deteriorated, is now a treasure of the Museo Naval in Madrid.

The configuration of the land and its positioning is more or less exact depending on the regions. The date of the map has been a question of some controversy, but it is actually dated under a vignette, at the level of Honduras, depicting Saint Christopher carrying baby Jesus across water: “Juan de la Cosa la fizo en el puerto de S. mª. en el año de 1500” (Juan de la Cosa made it in the port of Santa Maria in the year 1500). Santa Maria is a small port at the mouth of the Guadalquivir River near Cadiz (Macias, p. 3: for this reference and subsequent ones, see the full entry in the bibliography).

Why were the flags along the Atlantic coast identified as English? One reason is the inscription “Mar descubierta por inglese[s]” (Sea discovered by the English) near the two southernmost flags and “Cavo de Ynglaterra” (Cape of England) just above the northernmost one, which is believed to mark the point of John Cabot’s landfall in 1497. Although the geographical location corresponding to the positioning of the latter inscription has given rise to much speculation, there is no way of pinpointing a precise place on this map because of the lack of precision in that particular region. Still, the flags could be viewed as English by a process of elimination.

First let as look at the possibility that they could be Portuguese. We know that João Fernandes reached Greenland in 1499, which he named “Terra de Labrador” (land of the ploughman, or landowner). The fact that this name would later be applied to Labrador as we know it today indicates how fluid the knowledge of geographical locations was at the time. Only a year later, Gaspar Corte-Real likely reached the coast of Newfoundland (Hayes, p. 20-21, 24). But the flags representing Portugal on early maps usually are Azure five plates in saltire and a bordure Gules (five white roundels arranged in saltire on a blue field within a red border). The same flag also appears without a bordure. At times, the plates are not visible, and all that can be distinguished is a field and the bordure. Examples of these Portuguese flags can be seen on Pedro Reinel’s map of 1504 (Hayes, p. 22), and on a detail of Alberto Cantino’s planisphere of 1502 showing Portuguese mining and trading interests on the Gold Coast of Africa, in the vicinity of Sierra Leone and St. George Castle at Elmina (Dor-Ner, p. 73).

De la Cosa, for his own part, represented Portugal with a variety of flags. Off the coast of Africa, we see three Portuguese caravels. Two fly a white flag with a red bordure and another, nearer the coast, flaunts a pointed green or blue flag bearing a white square with five besants (yellow roundels) in saltire. On the Gold Coast, the banners appear white with a blue bordure while, in the area of Morocco where the Portuguese had expanded, we see a white field with a gold bordure. For the island of Madeira and the Azores, it is now a red field with a gold bordure (as seen on de la Cosa’s map in Marcias, p. 21 and Hayes, p. 19). The variety of colours may be inconsistencies on the part of the creator or may be the result of retouches or chemical reactions that modified the pigments over the years. The fact that I am working from a photographic reproduction should also be taken into account. In any case, because all flags representing Portugal on de la Cosa’s map, except one naval flag, have the characteristic bordure, we can be reasonably sure that the five flags along the North Atlantic coast are not Portuguese.

The quarterly Argent and Sable flags are present elsewhere on the map, namely one above Iceland and another above Scandinavia, which at least opens up a serious possibility that they represent Norse territories and explorations. It should not be particularly surprising to find the same flags along the north Atlantic coast since, at the time, Greenland, which was discovered and settled by the Norse, was viewed as being part of the North American continent, not as an island (Hayes, p. 24). As Skelton points out (see bibliography), the North Atlantic coastline on de la Cosa’s map “has been variously held to represent the north shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence; the south coast of Newfoundland; the east coasts of Newfoundland and Labrador; Nova Scotia and Newfoundland; or even the west coast of Greenland.”

Unlike the other three flags, the two quarterly Argent and Gules ones are found only along the North Atlantic coast. If they had appeared elsewhere on the map, a more assured identification might have been possible, but this is not the case. Still, by the simple process of eliminating other possible countries and the presence nearby of inscriptions referring to England or the English, the two flags are likely meant to represent England. The alternation of the two types of flags seems to confirm that the cartographer, who probably worked from an indirect account of Cabot’s voyages (Macias, p. 23), saw the coast of Greenland and the coast of North America that Cabot had discovered as being within the same general area.

We note that, further south, de la Cosa replicates many examples of the Spanish flag of Castile and Leon as it existed at the time. Why did he not do the same for Scandinavia and England, if indeed the flags were meant to represent these countries? It must be kept in mind that the notion of national flag was not, at that time, as well established as it is today. The Kalmar Union (1397–1523) that united Denmark, Norway and Sweden under a single monarch was identified by a gold flag with a red cross, but de la Cosa, working in Santa Maria in 1500, may not have known this. The same situation may also have existed for the flags that identified England or the English sovereign at the time. Within the same time period, cartographers identified England with the red cross of St. George on a white shield, for instance on the aforementioned Cantino’s planisphere of 1502 and Reinel’s map of 1504 (Hayes, p. 21-22), but de la Cosa may not have been aware of this as it was a recent and, as it seems, a passing development in cartography.

The reinterpretation of de la Cosa’s five North Atlantic flags as being three Norse and two English, and a Norse flag occupying the southernmost position, is of considerable importance in supporting a northerly latitude for Cabot’s point of landing.

Note: De la Cosa’s entire map can be found at several sites on the Internet. There is also a good reproduction with a detail of the Atlantic Coast in Hayes, p. 18-19.

Bibliography

Dor-Ner, Zvi. Columbus and the Age of Discovery. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1991.

Hayes, Derek. Historical Atlas of Canada. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2002.

Macias, Luis A. Robles. “Juan de la Cosa’s Projection: A Fresh Analysis of the Earliest Preserved Map of the Americas,” 24 May 2010, consulted Jan. 2, 2012 at: http://www.stonybrook.edu/libmap/coordinates/seriesa/no9/a9.pdf.

Skelton, R. A. “John (Giovanni) Cabot (Caboto)” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, consulted Jan. 2, 2012 at: http://www.biographi.ca/009004-119.01-e.php?&id_nbr=101.