ANNEX II

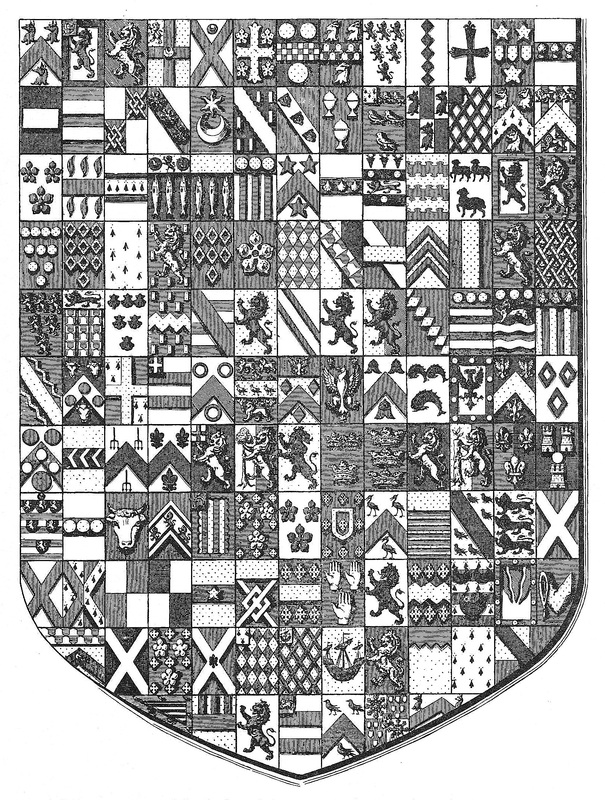

A personal shield with 135 quarters from Fox-Davies, The Art of Heraldry, 1904, p. 375. There are 134 families represented in this accumulation of quarterings, the first quarter being also repeated as the last quarter.

How would one go about determining to which family such a huge agglomeration of arms belonged, if it were not already known? Since the owner is already identified, what follows is meant to illustrate a route to take if similar arms were found, for instance, on a bookplate without a name.

As for other quartered arms, one begins by identifying the first quarter. A close look at this quarter, perhaps with a magnifying glass, reveals that only two tinctures are involved, the white surface indicating argent and the vertical lines representing gules. Animals are not always easy to identify, but a fox seems the most likely candidate because of the particularly pointed snout. The blazon can thus be established, at least tentatively, as Argent a chevron between three foxes’ heads erased Gules. The word erased refers to the jagged edges at base of the neck.

It is always good to know the country of origin of the arms, something which is sometimes apparent from the object on which they are depicted. At times an educated guess is a good avenue. If one concludes that the shield belongs to the United Kingdom, the next step would be to go to John W. Papworth, An Alphabetical Dictionary of Coats of Arms Belonging to Families in Great Britain and Ireland, Forming an Extensive Ordinary of British Armorials. In the “Table of Alphabetical Titles” which follows the introduction, the word chevron (the main charge) appears with a page number. Flipping through the pages from that number, one arrives at the category “one chevron between heads (beasts)” and then to “fox” where the names William Awys, Fairfax, John Fox, Fox and Lane-Fox are seen.

Since the name Fox is present in many counties, it seems logical to look at this name before the others. Should the researcher decide to consult Burke’s General Armory first, the work would confirm that some Fox families used arms as the one blazoned, but would yield little useful information for a specific person. One work that would be consulted eventually is Fox-Davies’ Armorial Families. In there under Fox, one would find the heraldic description of the 135 quarters, the name of each family to whom they belonged, and another illustration of the same arms. The last heir to the arms in 1929 is also revealed as Louisa Emma Lane-Fox.

In this case, the identification proved rather easy because the arms are well documented. Still the research could have taken many lateral tangents, such as deciding that the animals were wolves rather than fox, researching first the other names Awys or Fairfax mentioned in Papworth or, since the approach here is hypothetical, discovering that the arms were not from the United Kingdom at all. Many times when doing this type of research, the first quarter is found to belong to several names. This can also be true of the second quarter. With the names in hand, it is necessary to search through lists of marriages to find a nuptial connexion between two of the names. The amount of time required to do this will vary considerably from one case to another and depends on the strategy adopted. When many names are involved, it can become a formidable task. When it is not be possible to identify the first quarter, it becomes easy to get bogged down.

If two of the quarters can be identified somewhere within the shield and a marriage between the two names is discovered, it may be possible to work one’s way up to the original owner represented in the first and last quarters. This might lead to the owner of the arms at the time they were depicted. Besides a knowledge of heraldry, the process requires exceptional genealogical skills and a willingness to spend countless hours of work, perhaps on and off over days, even months or years. Most arms are represented with only a few of the quarters to which the owner is entitled, but this can make things even worse because the inheritance sequence is disrupted as a result.

The shield illustrated here can undoubtedly be an El Dorado for genealogists, but like mining for gold, it requires a great deal of work and patience. Quarters enter the shield by descent when an armigerous man marries an armigerous heiresses or co-heiresses, which happens sporadically, not at every generation. Even when the families to whom the quarters belong are known, discovering by which marriage each quarter entered the shield entails lengthy genealogical investigation.

The works I consulted in this case are all online and can be viewed by the reader;

1) Papworth’s Ordinary of British Armorials, pp. xvii, 437:

https://books.google.ca/books?id=dTABAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false;

2) Burke’s General Armrory, p. 582: http://www.archive.org/stream/generalarmoryofe00burk#page/n5/mode/2up;

3) Fox-Davies, Armorial Families, pp. 710-12:

https://archive.org/stream/armorialfamilies01foxd#page/712/mode/2up.

The three works were accessed on 11 November 2015.

Appendix III offers more specific advice on identifying coats of arms.

As for other quartered arms, one begins by identifying the first quarter. A close look at this quarter, perhaps with a magnifying glass, reveals that only two tinctures are involved, the white surface indicating argent and the vertical lines representing gules. Animals are not always easy to identify, but a fox seems the most likely candidate because of the particularly pointed snout. The blazon can thus be established, at least tentatively, as Argent a chevron between three foxes’ heads erased Gules. The word erased refers to the jagged edges at base of the neck.

It is always good to know the country of origin of the arms, something which is sometimes apparent from the object on which they are depicted. At times an educated guess is a good avenue. If one concludes that the shield belongs to the United Kingdom, the next step would be to go to John W. Papworth, An Alphabetical Dictionary of Coats of Arms Belonging to Families in Great Britain and Ireland, Forming an Extensive Ordinary of British Armorials. In the “Table of Alphabetical Titles” which follows the introduction, the word chevron (the main charge) appears with a page number. Flipping through the pages from that number, one arrives at the category “one chevron between heads (beasts)” and then to “fox” where the names William Awys, Fairfax, John Fox, Fox and Lane-Fox are seen.

Since the name Fox is present in many counties, it seems logical to look at this name before the others. Should the researcher decide to consult Burke’s General Armory first, the work would confirm that some Fox families used arms as the one blazoned, but would yield little useful information for a specific person. One work that would be consulted eventually is Fox-Davies’ Armorial Families. In there under Fox, one would find the heraldic description of the 135 quarters, the name of each family to whom they belonged, and another illustration of the same arms. The last heir to the arms in 1929 is also revealed as Louisa Emma Lane-Fox.

In this case, the identification proved rather easy because the arms are well documented. Still the research could have taken many lateral tangents, such as deciding that the animals were wolves rather than fox, researching first the other names Awys or Fairfax mentioned in Papworth or, since the approach here is hypothetical, discovering that the arms were not from the United Kingdom at all. Many times when doing this type of research, the first quarter is found to belong to several names. This can also be true of the second quarter. With the names in hand, it is necessary to search through lists of marriages to find a nuptial connexion between two of the names. The amount of time required to do this will vary considerably from one case to another and depends on the strategy adopted. When many names are involved, it can become a formidable task. When it is not be possible to identify the first quarter, it becomes easy to get bogged down.

If two of the quarters can be identified somewhere within the shield and a marriage between the two names is discovered, it may be possible to work one’s way up to the original owner represented in the first and last quarters. This might lead to the owner of the arms at the time they were depicted. Besides a knowledge of heraldry, the process requires exceptional genealogical skills and a willingness to spend countless hours of work, perhaps on and off over days, even months or years. Most arms are represented with only a few of the quarters to which the owner is entitled, but this can make things even worse because the inheritance sequence is disrupted as a result.

The shield illustrated here can undoubtedly be an El Dorado for genealogists, but like mining for gold, it requires a great deal of work and patience. Quarters enter the shield by descent when an armigerous man marries an armigerous heiresses or co-heiresses, which happens sporadically, not at every generation. Even when the families to whom the quarters belong are known, discovering by which marriage each quarter entered the shield entails lengthy genealogical investigation.

The works I consulted in this case are all online and can be viewed by the reader;

1) Papworth’s Ordinary of British Armorials, pp. xvii, 437:

https://books.google.ca/books?id=dTABAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false;

2) Burke’s General Armrory, p. 582: http://www.archive.org/stream/generalarmoryofe00burk#page/n5/mode/2up;

3) Fox-Davies, Armorial Families, pp. 710-12:

https://archive.org/stream/armorialfamilies01foxd#page/712/mode/2up.

The three works were accessed on 11 November 2015.

Appendix III offers more specific advice on identifying coats of arms.