Why Was the Beaver Left Out of Canada’s Coat of Arms?

Auguste Vachon, Outaouais Herald Emeritus

The beaver identifies with Canada in many ways. For some 250 years, from the beginning of the seventeenth century, the beaver was at the heart of the fur trade which was a commercial pillar of the country. It has many qualities common to people living in colder parts of the world where they are required to use all their knowledge, skill and patience to ensure their survival. While such traits are admirable, they are not as appreciated, at a symbolic level, as the attributes of the regal looking lion, king of beasts, reputed for its strength and courage and the imperial looking eagle, king of birds that can soar to great heights. The beaver’s appearance is another factor that can cast doubts as to its suitability as an emblem. The animal is a rodent with short legs and a humped back that moves in a crawling position with its nose, belly and tail close to the ground. Another important reason for excluding the beaver from Canada’s coat of arms was a matter of mentality. The coat of arms was created just after the First World War at a time when many Canadians looked to the British Empire with emotional attachment and with a strong resolve to preserve its unity as their one source of protection, well-being and prosperity. The members of the committee that designed Canada’s armorial emblem wanted above all to emphasize their links to the monarchy and empire with few Canadian symbols. Because the subject becomes rather complex, a summary has been added at the end of this study.

N.B.

All the websites referred to were accessed on 23 June 2017.

All the websites referred to were accessed on 23 June 2017.

Commercial Exploitation

It is well known that beaver pelts served to create garments and beaver hats. The hats were made of a felt produced from the soft inner coating of fur called beaver wool which was shaven off and processed. Beavers were also a source of food for the First Nations as well as for explorers and woodsmen and are still eaten as wild game. In his diary of Sanford Fleming’s expedition across Canada in1872, George Munro Grant describes a meal where a beaver was on the menu: “… the five who had never tasted beaver, prepared themselves to sit in judgment. The verdict was favourable throughout; the meat tender, though dry, the liver a delicious morsel, and the tail superior to the famous moose-muffle. … scarcely a scrap was left to show what he once had been.” [1]

The beaver has long been valued for its castoreum which was considered a remedy for many ills. Naturalists going back to Antiquity believed that castoreum was lodged in the beaver’s testicles and that, when pursued by a hunter, the beaver would bite them off leaving this precious commodity to his pursuer and thus saving its life. We still find this notion perpetrated in Samuel Johnson’s famous Dictionary, first published in 1755 and reedited many times: “The beaver being hunted, biteth off his stones knowing that for them only his life is sought.” The self-castration story was already ridiculed, almost a century before, by Louis Nicolas, a Jesuit missionary stationed in New France from 1664 to1674. Being a close observer of nature, Nicolas states that the beaver has four testicles, two of them containing the castoreum which has important medicinal properties, and the other two being of no use but to feed the dogs. Nicolas further discredits the notion that castoreum has a pleasant odour, insisting that it actually smells quite foul, see: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/de-preacutecieux-bijoux-de-famille--une-leacutegende-au-sujet-du-castor.html.

A second author to contradict the self mutilation legend was Louis Armand de Lom d'Arce, baron de La Hontan. In his 1703 work entitled New Voyages, he rightly states that the castoreum is not contained in the testicles of the beaver but in other bags provided by nature and that the secretion serves to clean their teeth after biting into a gummy shrub. He also points out that the pelt of the beaver is worth far more than its castoreum. [2] We know today that castoreum serves to waterproof the beaver’s fur and mark its territory with its scent. Still the notion that castoreum is from the testicles of the beaver has persisted to this day. It is still found under castoréum in Le nouveau Petit Robert de la langue française 2007. Because of its commercial value, the beaver was considered an emblem of Canada very early in the history of the country, see: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/chapter-2-the-beaver-and-maple-leaf.html.

It is well known that beaver pelts served to create garments and beaver hats. The hats were made of a felt produced from the soft inner coating of fur called beaver wool which was shaven off and processed. Beavers were also a source of food for the First Nations as well as for explorers and woodsmen and are still eaten as wild game. In his diary of Sanford Fleming’s expedition across Canada in1872, George Munro Grant describes a meal where a beaver was on the menu: “… the five who had never tasted beaver, prepared themselves to sit in judgment. The verdict was favourable throughout; the meat tender, though dry, the liver a delicious morsel, and the tail superior to the famous moose-muffle. … scarcely a scrap was left to show what he once had been.” [1]

The beaver has long been valued for its castoreum which was considered a remedy for many ills. Naturalists going back to Antiquity believed that castoreum was lodged in the beaver’s testicles and that, when pursued by a hunter, the beaver would bite them off leaving this precious commodity to his pursuer and thus saving its life. We still find this notion perpetrated in Samuel Johnson’s famous Dictionary, first published in 1755 and reedited many times: “The beaver being hunted, biteth off his stones knowing that for them only his life is sought.” The self-castration story was already ridiculed, almost a century before, by Louis Nicolas, a Jesuit missionary stationed in New France from 1664 to1674. Being a close observer of nature, Nicolas states that the beaver has four testicles, two of them containing the castoreum which has important medicinal properties, and the other two being of no use but to feed the dogs. Nicolas further discredits the notion that castoreum has a pleasant odour, insisting that it actually smells quite foul, see: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/de-preacutecieux-bijoux-de-famille--une-leacutegende-au-sujet-du-castor.html.

A second author to contradict the self mutilation legend was Louis Armand de Lom d'Arce, baron de La Hontan. In his 1703 work entitled New Voyages, he rightly states that the castoreum is not contained in the testicles of the beaver but in other bags provided by nature and that the secretion serves to clean their teeth after biting into a gummy shrub. He also points out that the pelt of the beaver is worth far more than its castoreum. [2] We know today that castoreum serves to waterproof the beaver’s fur and mark its territory with its scent. Still the notion that castoreum is from the testicles of the beaver has persisted to this day. It is still found under castoréum in Le nouveau Petit Robert de la langue française 2007. Because of its commercial value, the beaver was considered an emblem of Canada very early in the history of the country, see: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/chapter-2-the-beaver-and-maple-leaf.html.

Positive and Negative Views

The beaver is known for its skill and ingenuity as a master builder of dams, huts, and canals to float logs. It is persistent in the sense that, if its dams or hut are damaged, it will take steps to repair it at the first safe opportunity. The community instinct of beavers is apparent in the care they take of their young (fig. 1) and the fact that they live in colonies and work as teams. If a beaver senses danger, it will strike the water with its tail creating a loud bang to warn others. Beavers store freshly cut wood under water for winter food. They are vegetarian and relatively peaceful showing aggressive behaviour only when they are themselves aggressed. They have a strong sense of preservation and will chew off their paw to save their life if caught in the jaws of a trap. They create wetlands for other animals and help control the flow of water to prevent flooding. Their ponds act as settling reservoirs to remove impurities from water and make it cleaner downstream. In other words, the beaver incarnates a wide range of qualities that make it a highly symbolic animal. Conversely if not controlled, the beaver can flood roads by blocking culverts and destroy trees by gnawing at them or flooding their roots causing them to die. Sometimes they chew the bark around conifers cutting off their nourishment and killing them.

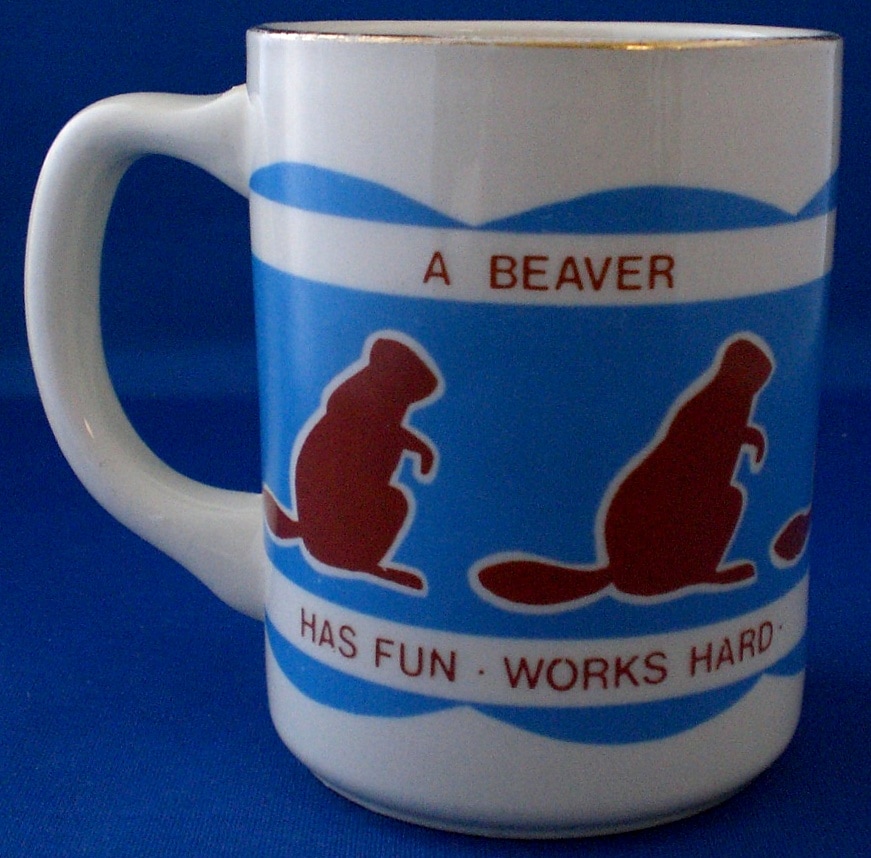

The beaver is known for its skill and ingenuity as a master builder of dams, huts, and canals to float logs. It is persistent in the sense that, if its dams or hut are damaged, it will take steps to repair it at the first safe opportunity. The community instinct of beavers is apparent in the care they take of their young (fig. 1) and the fact that they live in colonies and work as teams. If a beaver senses danger, it will strike the water with its tail creating a loud bang to warn others. Beavers store freshly cut wood under water for winter food. They are vegetarian and relatively peaceful showing aggressive behaviour only when they are themselves aggressed. They have a strong sense of preservation and will chew off their paw to save their life if caught in the jaws of a trap. They create wetlands for other animals and help control the flow of water to prevent flooding. Their ponds act as settling reservoirs to remove impurities from water and make it cleaner downstream. In other words, the beaver incarnates a wide range of qualities that make it a highly symbolic animal. Conversely if not controlled, the beaver can flood roads by blocking culverts and destroy trees by gnawing at them or flooding their roots causing them to die. Sometimes they chew the bark around conifers cutting off their nourishment and killing them.

Fig. 1. The blue band on this cup is decorated with a frieze of five brown crouching beavers (sejant in heraldic language). The white bands are inscribed: A BEAVER HAS FUN WORKS HARD/ A BEAVER HELPS HIS FAMILY AND FRIENDS. It is interesting that the beaver is given human characteristics by such phrases as “has fun” and “helps his family and friends.” Cup decorated in Canada by Creemore China & Glass, Creemore, Ontario. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

Both positive and negative views of the beaver have coexisted for many years. The fabulist Jean de La Fontaine (1621-1695) found it necessary to defend beavers against criticism. After describing their skill and teamwork when building dams and huts, he adds: “That beavers are only a body without a mind/No one will ever get me to believe.” [3] This implies that beavers were seen as brainless creatures by some commentators of his or previous times. La Fontaine’s view of the beaver is much romanticized not unlike a scene on a 1698 map of the Americas by Nicolas de Fer where a colony of beavers is building a dam below Niagara Falls. The workers are divided by trade into woodcutters, carpenters, masons, haulers, etc., all under the supervision of a beaver-architect. There is also an attendant for the sick, and a worker lying on its back suffering wear to its tail from overuse to transport mortar and to compact the assembled materials.

On 27 November 1863, Sir John William Dawson, principal of McGill University in Montreal, delivered the annual lecture entitled "Duties of Educated Young Men in British America." Dawson states that Canada has two emblems, the beaver and maple.

“Canada has two emblems which have often appeared to some to point out its position in these respect, ―the Beaver and the Maple. The beaver in his sagacity, his industry, his ingenuity, and his perseverance, is a most respectable animal; a much better emblem for an infant country than the rapacious eagle or even the lordly lion; but he is also a type of unvarying instincts and old-world traditions. He does not improve, and becomes extinct rather than change his ways. The maple, again, is the emblem of the vitality and energy of a new country; vigorous and stately in its growth, changing its hues as the seasons change, equally at home in the forest, in the cultivated field, and stretching its green boughs over the dusty streets, it may well be received as a type of the progressive and versatile spirit of a new and growing country.

“Some of our artists have the bad taste to represent the beaver as perched on the maple bough; a most unpleasant position for the poor animal, and suggestive of the thought that he is in the act of gnawing through the trunk of our national tree [the maple]. Perhaps some more venturous designer may some day reverse the position, and represent the maple branch as fashioned into a club, wherewith to knock the beaver on the head.” [4]

Dawson views the skillful and industrious beaver as a better emblem for a young country than the “rapacious eagle” of the United States or the “lordly lion” of England, but he also emphasizes that the maple is a more appropriate emblem for Canada than the beaver. Of course Dawson is speaking to students in a moralizing tone, but his criticism that the beaver becomes extinct because it is unwilling to change its ways is proven wrong today. The beaver came back with a vengeance after it stopped being trapped to near extinction. The thought that the beaver should be knocked on the head with a maple club because he is gnawing at the national tree dramatically reinforces Dawson’s bias in favour of the maple as the more suitable emblem for Canada. His image of a beaver perched on a maple bough is intriguing. The only image which seems to fit the bill at the time is seen on a table services c. 1856 manufactured by Edward Walley of Staffordshire, England (fig. 2). Walley produced a large number of these services with slight variations. According to Elizabeth Collard, these sets were associated with the St. Jean Baptiste Society and educational institutions and may have been used in seminaries and colleges, although a number of them were owned privately. [5] It is very possible that Dawson was referring to this design which he likely encountered at one time or another in Montreal where he lived.

On 27 November 1863, Sir John William Dawson, principal of McGill University in Montreal, delivered the annual lecture entitled "Duties of Educated Young Men in British America." Dawson states that Canada has two emblems, the beaver and maple.

“Canada has two emblems which have often appeared to some to point out its position in these respect, ―the Beaver and the Maple. The beaver in his sagacity, his industry, his ingenuity, and his perseverance, is a most respectable animal; a much better emblem for an infant country than the rapacious eagle or even the lordly lion; but he is also a type of unvarying instincts and old-world traditions. He does not improve, and becomes extinct rather than change his ways. The maple, again, is the emblem of the vitality and energy of a new country; vigorous and stately in its growth, changing its hues as the seasons change, equally at home in the forest, in the cultivated field, and stretching its green boughs over the dusty streets, it may well be received as a type of the progressive and versatile spirit of a new and growing country.

“Some of our artists have the bad taste to represent the beaver as perched on the maple bough; a most unpleasant position for the poor animal, and suggestive of the thought that he is in the act of gnawing through the trunk of our national tree [the maple]. Perhaps some more venturous designer may some day reverse the position, and represent the maple branch as fashioned into a club, wherewith to knock the beaver on the head.” [4]

Dawson views the skillful and industrious beaver as a better emblem for a young country than the “rapacious eagle” of the United States or the “lordly lion” of England, but he also emphasizes that the maple is a more appropriate emblem for Canada than the beaver. Of course Dawson is speaking to students in a moralizing tone, but his criticism that the beaver becomes extinct because it is unwilling to change its ways is proven wrong today. The beaver came back with a vengeance after it stopped being trapped to near extinction. The thought that the beaver should be knocked on the head with a maple club because he is gnawing at the national tree dramatically reinforces Dawson’s bias in favour of the maple as the more suitable emblem for Canada. His image of a beaver perched on a maple bough is intriguing. The only image which seems to fit the bill at the time is seen on a table services c. 1856 manufactured by Edward Walley of Staffordshire, England (fig. 2). Walley produced a large number of these services with slight variations. According to Elizabeth Collard, these sets were associated with the St. Jean Baptiste Society and educational institutions and may have been used in seminaries and colleges, although a number of them were owned privately. [5] It is very possible that Dawson was referring to this design which he likely encountered at one time or another in Montreal where he lived.

Fig. 2 This plate is part of a table service manufactured c. 1856 by Edward Walley of Cobridge, Staffordshire, England. It features the beaver perched on a maple branch with abundant leaves and is inscribed with the motto of the Société Saint-Jean Baptiste Nos institutions! notre langue et nos lois. (Our institutions! our language and our laws), and that of the Department of Public Instruction Labor omnia vincit. (Work conquers everything). Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

The imagery of the beaver “perched on the maple bough” appears, repeated twice, with a portrait of Sir John William Dawson which precedes the title page in volume one of Tuttle’s History of the Dominion. The rodent is on a branch and bites into it just as described by Dawson. However, Tuttle’s work was published in 1877, some 14 years after Dawson’s lecture, and the portraits of others, namely the Honourable Charles Tupper and the Honourable Alexander McKenzie are treated in the same way. [6] Any link between Dawson’s lecture and the beavers decorating his portrait becomes tenuous in light of these circumstances. Although the beaver is frequently paired with maple as the two emblems of Canada, the animal has a preference for aspen, poplar, cottonwood and willow. While beavers are frequently depicted cutting down a tree, printed imagery where that tree is unequivocally a maple is rare (see Appendix I).

Other controversial comments regarding the beaver were made after a coat of arms was granted to Canada in 1921. A correspondent wrote to the editor of the magazine Rod and Gun in Canada expressing his surprise that the beaver, as the emblem of Canada, was excluded from the arms of the country while the lion, emblem of England, was there holding a maple leaf (fig. 5):

“I happened to see the new coat of arms of the Dominion the other day and was much surprised and sorry to find that the Canadian beaver was left out, and in its place was a lion holding a maple leaf. The lion, as everybody in the Dominion knows, is not our emblem; it is the emblem of Great Britain. The beaver is our emblem, or at least I have always been taught that it was, and from my point of view, should never be left out of our coat of arms.” [7]

The reply came from Thomas Mulvey, under-secretary of state for Canada, who had been chairman of the committee responsible for the choice of Canada’s armorial bearings. His observations are interesting because they tell us why the beaver was excluded after due consideration by members of the committee:

“The Committee having charge of the recommendation of Arms considered fully the suggestion that the Beaver should be included, and it was decided that as a member of the Rat Family, a Beaver was not appropriate and would not look well on the device. One example of the objections raised is quite well known. The Canadian Merchant Marine displayed a Beaver on their House-Flag, and they have ever since been colloquially known as ‘The Rat Line.’ As your correspondent says, the Lion is not the representative of Canada except in so far as Canada is a part of the British Empire, and in this connection it was considered appropriate to have the Lion hold the Maple Leaf.” [8]

The house flag with a beaver mentioned by Mulvey did not belong to the Canadian Merchant Marine that flew the Canadian Red Ensign. It belonged to the Beaver Line formed in 1867 as the Canada Steamship Company. Because of the beaver on their flag, the company became known as the Beaver Line (see Appendix II).

As a member of the rat family, Mulvey felt that a beaver would not look well in Canada’s achievement of arms, but a different opinion regarding the heraldic propriety of the rodent was expressed in 1968 by Conrad Swan, then Rouge Dragon Pursuivant of Arms of the College of Arms in London:

“The reason why each, the Beaver and the Maple leaf, became so popular in Canadian heraldry stems, I would submit, from the fact that the best charges in armory are those capable of a clear and distinctive silhouette. Such a characteristic renders an armorial device capable of fulfilling its essential and functional purpose of identification even at considerable distances—as when displayed on banners or flags. Both the Beaver and the Maple leaf fulfil this requirement admirably.

“Of the two the maple leaf is the more adaptable. The most characteristic position of the beaver is, possibly, when on all fours with its belly and head close to the ground, the body rises to the mound-like hind quarters and then terminates in that unmistakable rudder-like tail. An equally distinctive position is sejant, that is to say, seated on its rump.” (As in fig. 1) [9]

In support of Swan’s favourable statements towards the beaver, it can be added that the animal appears in the crest of both the province of Manitoba and Alberta without looking ridiculous. Beavers can make good supporters as in the case of the achievement of arms of the Royal Heraldry Society of Canada, see http://www.heraldry.ca/. The lion has been stylized for many years and it is no less recognizable on that account. The beaver is frequently stylized effectively in caricature (fig. 3), but it seems that attempts at stylisation to make it a dignified creature as required by heraldry are more difficult. One form of stylisation which might prove effective would be to draw the beaver, not in natural colours but in heraldic colours and, as hinted by Swan, as a silhouette with only the contour, the eye and a few lines. This treatment, seen on some beaver weathervanes, proves quite effective.

Other controversial comments regarding the beaver were made after a coat of arms was granted to Canada in 1921. A correspondent wrote to the editor of the magazine Rod and Gun in Canada expressing his surprise that the beaver, as the emblem of Canada, was excluded from the arms of the country while the lion, emblem of England, was there holding a maple leaf (fig. 5):

“I happened to see the new coat of arms of the Dominion the other day and was much surprised and sorry to find that the Canadian beaver was left out, and in its place was a lion holding a maple leaf. The lion, as everybody in the Dominion knows, is not our emblem; it is the emblem of Great Britain. The beaver is our emblem, or at least I have always been taught that it was, and from my point of view, should never be left out of our coat of arms.” [7]

The reply came from Thomas Mulvey, under-secretary of state for Canada, who had been chairman of the committee responsible for the choice of Canada’s armorial bearings. His observations are interesting because they tell us why the beaver was excluded after due consideration by members of the committee:

“The Committee having charge of the recommendation of Arms considered fully the suggestion that the Beaver should be included, and it was decided that as a member of the Rat Family, a Beaver was not appropriate and would not look well on the device. One example of the objections raised is quite well known. The Canadian Merchant Marine displayed a Beaver on their House-Flag, and they have ever since been colloquially known as ‘The Rat Line.’ As your correspondent says, the Lion is not the representative of Canada except in so far as Canada is a part of the British Empire, and in this connection it was considered appropriate to have the Lion hold the Maple Leaf.” [8]

The house flag with a beaver mentioned by Mulvey did not belong to the Canadian Merchant Marine that flew the Canadian Red Ensign. It belonged to the Beaver Line formed in 1867 as the Canada Steamship Company. Because of the beaver on their flag, the company became known as the Beaver Line (see Appendix II).

As a member of the rat family, Mulvey felt that a beaver would not look well in Canada’s achievement of arms, but a different opinion regarding the heraldic propriety of the rodent was expressed in 1968 by Conrad Swan, then Rouge Dragon Pursuivant of Arms of the College of Arms in London:

“The reason why each, the Beaver and the Maple leaf, became so popular in Canadian heraldry stems, I would submit, from the fact that the best charges in armory are those capable of a clear and distinctive silhouette. Such a characteristic renders an armorial device capable of fulfilling its essential and functional purpose of identification even at considerable distances—as when displayed on banners or flags. Both the Beaver and the Maple leaf fulfil this requirement admirably.

“Of the two the maple leaf is the more adaptable. The most characteristic position of the beaver is, possibly, when on all fours with its belly and head close to the ground, the body rises to the mound-like hind quarters and then terminates in that unmistakable rudder-like tail. An equally distinctive position is sejant, that is to say, seated on its rump.” (As in fig. 1) [9]

In support of Swan’s favourable statements towards the beaver, it can be added that the animal appears in the crest of both the province of Manitoba and Alberta without looking ridiculous. Beavers can make good supporters as in the case of the achievement of arms of the Royal Heraldry Society of Canada, see http://www.heraldry.ca/. The lion has been stylized for many years and it is no less recognizable on that account. The beaver is frequently stylized effectively in caricature (fig. 3), but it seems that attempts at stylisation to make it a dignified creature as required by heraldry are more difficult. One form of stylisation which might prove effective would be to draw the beaver, not in natural colours but in heraldic colours and, as hinted by Swan, as a silhouette with only the contour, the eye and a few lines. This treatment, seen on some beaver weathervanes, proves quite effective.

Fig. 3. The beaver is frequently represented in caricature and lends itself well to this type of depiction. It is harder to render in heraldic art where it should have a dignified countenance. Cup by CAE, England, decorated in Canada. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History. For beavers in caricature and cartoons, see: https://www.google.ca/search?q=caricatures+beavers&tbm=isch&imgil=XdvrqxVO8ZlTpM%253A%253BHvRNRmK1fGdMYM%253Bhttps%25253A%25252F%25252Fwww.pinterest.com%25252Fpin%25252F526639750146132914%25252F&source=iu&pf=m&fir=XdvrqxVO8ZlTpM%253A%252CHvRNRmK1fGdMYM%252C_&usg=__uyPVA-ilRF9LGUuq1mdVza1PJGE%3D&biw=1280&bih=894&ved=0ahUKEwj3gb-ygaTUAhUh5IMKHZskBccQyjcIMw&ei=0uQzWffQKaHIjwSbyZS4DA#imgrc=XdvrqxVO8ZlTpM.

A Question of Beliefs

The most forceful member of the committee that designed Canada’s achievement of arms was Sir Joseph Pope, under-secretary of state for External Affairs. He had not promoted a distinctive flag for Canada because he believed that Canadians should be happy to live under the Union Jack: “the ‘Union Jack’, pure and simple is good enough for me.” His stance was not just a personal preference: “A flag, as I understand it, is the emblem of sovereignty, and so long as we are part of the British Empire surely, we must fly the British Flag! I have no patience with those persons who would endeavour to rob us of this glorious inheritance.” [10] His mentality was like that of many Canadians of the time who strongly believed that close ties with the British Empire was a source of protection, prosperity and pride as forcefully expressed in figure 4 by the Union Jack and the inscriptions “One Flag, One Empire, One King.”

The most forceful member of the committee that designed Canada’s achievement of arms was Sir Joseph Pope, under-secretary of state for External Affairs. He had not promoted a distinctive flag for Canada because he believed that Canadians should be happy to live under the Union Jack: “the ‘Union Jack’, pure and simple is good enough for me.” His stance was not just a personal preference: “A flag, as I understand it, is the emblem of sovereignty, and so long as we are part of the British Empire surely, we must fly the British Flag! I have no patience with those persons who would endeavour to rob us of this glorious inheritance.” [10] His mentality was like that of many Canadians of the time who strongly believed that close ties with the British Empire was a source of protection, prosperity and pride as forcefully expressed in figure 4 by the Union Jack and the inscriptions “One Flag, One Empire, One King.”

Fig. 4. Postcard by Raphael Tuck & Sons entitled “Toronto – Exhibition Ground.” The slogan around the Union Jack reads “One Flag, One Empire, One King.” From the Auguste and Paula Vachon collection of postcards. The card was first used on 6 October 1912: https://tuckdb.org/postcards/105320.

It is interesting that Sir Joseph Pope did not promote the identification of Canada by the royal arms of the United Kingdom as he had done for the Union Jack. In fact he believed that the country had been granted proper arms in 1868, the only problem being that other provincial and territorial arms, often freely adopted devices, were added to the shield of the arms of the four original provinces. In 1904, in an effort to promote proper usage, he published a colour print of the four province arms with the title: “Armorial Bearings of the Dominion of Canada Authorized by Royal Warrant 26th May 1868.” (See figure 14: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/dominion-shields.html). By the time he served on the arms committee created in 1919, Pope knew that Canada had not been granted proper arms in 1868, only a shield to appear on the united provinces’ common seal. He then endorsed the idea that the arms of the country should not just be “an aggregation of the Arms of the Provinces.” As a member of the committee, he strongly advocated that the Canada’s arms should be royal arms, in spite of Garter King of Arms’ objection that the composition of the royal arms had been determined by the proclamation of 1801 creating the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. New royal arms would conflict with the proclamation. The impasse was resolved by making the grant the object of a new royal proclamation.

As a booklet was being prepared to introduce Canada’s 1921 arms, Pope refused to be associated with a statement that placed Canada on the same level as the old Kingdom of Scotland: “... the Dominion of Canada being on equality of status with the ancient Kingdom of Scotland. I do not wish to be associated with any such statement and I would suggest that the simplest way would be that my name might be left out.” [11] Pope was unwilling to endorse anything that would disturb the equilibrium within the empire. His observation surely had some influence since this assertion did not appear in the early publications on the arms of Canada by the government.

A 1925 letter to his son Maurice gives us further insight into the relation he favoured between the Dominions and the empire: “How are we going to get on when every member claims an equal status with the rest; where each Dominion shall have . . . not only an army and navy, but also diplomacy of its own? To my way of thinking such an Empire is an impossibility. I must leave the solution of the problem to younger and more vigorous minds than mine.” His contribution has been described thus: “Pope was the quintessential civil servant – capable, careful, perceptive – but by the 1920s he was felt to be old-fashioned and stiff. Indeed, he had become Ottawa’s arbiter of diplomatic niceties and social forms.” [12]

Popes Memoirs inform us of the decision taken at the first meeting of the committee choosing arms for Canada. The aggregate of provincial arms was completely rejected in favour of distinct arms which would include: “1) The Monarchical principle; 2) The French Regime and 3) Something Canadian such as the maple leaf.” [13] In the hierarchy of the committee, the maple leaf comes last. It is interesting that in a letter dated 8 June 1914, Pope enunciates the same principles for the arms of Canada but omits any Canadian content. [14] This opens the possibility that other members of the committee insisted on the inclusion of the maple leaf. The monarchical principle was emphasized by the composition mostly patterned on the arms of the United Kingdom and the insistence of the committee that the arms should be royal arms for Canada. The principles enunciated by the committee from the start of its deliberation were exactly what the composition of Canada’s coat of arms would become in the end (fig. 5).

It is certain that Pope did not want royal arms that would emphasize Canada at the expense of imperial content. This is no doubt the meaning of Mulveys statement in his letter to the editor of the magazine Rod and Gun in Canada quoted above “As your correspondent says, the Lion is not the representative of Canada except in so far as Canada is a part of the British Empire, and in this connection it was considered appropriate to have the Lion hold the Maple Leaf.”

Most of the components of Canada’s coat of arms reflect the country’s history as a colony of France and subsequently of Great-Britain. The crown had been placed spontaneously above the Dominion shields for some 50 years. It was normal that it be retained for the granted arms to highlight the fact that Canada is a constitutional monarchy. All the other components likewise have a historical link to Canada: the arms of the founding nations appearing on the shield and the flowers below the shield with the same significance, the Union Jack and banner of royal France which both flew on Canadian soil from early colonial days, the lion and unicorn which were part of the royal arms of the United Kingdom that dominated the Canadian scene for many years. Four components are Canadian: the sprig of maple in base of the shield, the red leaf in the paw of the lion, the colours in the mantling which became Canada’s colours and the motto which was proposed by Samuel Leonard Tilley, a Father of Confederation, to reflect the country’s geography.

The armorial bearings highlight Canada’s strong European roots with indications that it is becoming a country in its own right. Although Pope assuredly did not see it this way, the notion of royal arms for Canada is consistent with the assertion in the preamble to the Statute of Westminster of 1931 which gave the country its independence: “… inasmuch as the Crown is the symbol of the free association of the members of the British Commonwealth of Nations, and as they are united by a common allegiance to the Crown …” The fact that Canada’s arms paid homage to the country’s colonial past and the founding nations helped prepare Canadians to move on to something else for its flag, namely a red maple leaf as a unique symbol of the land and its people.

As a booklet was being prepared to introduce Canada’s 1921 arms, Pope refused to be associated with a statement that placed Canada on the same level as the old Kingdom of Scotland: “... the Dominion of Canada being on equality of status with the ancient Kingdom of Scotland. I do not wish to be associated with any such statement and I would suggest that the simplest way would be that my name might be left out.” [11] Pope was unwilling to endorse anything that would disturb the equilibrium within the empire. His observation surely had some influence since this assertion did not appear in the early publications on the arms of Canada by the government.

A 1925 letter to his son Maurice gives us further insight into the relation he favoured between the Dominions and the empire: “How are we going to get on when every member claims an equal status with the rest; where each Dominion shall have . . . not only an army and navy, but also diplomacy of its own? To my way of thinking such an Empire is an impossibility. I must leave the solution of the problem to younger and more vigorous minds than mine.” His contribution has been described thus: “Pope was the quintessential civil servant – capable, careful, perceptive – but by the 1920s he was felt to be old-fashioned and stiff. Indeed, he had become Ottawa’s arbiter of diplomatic niceties and social forms.” [12]

Popes Memoirs inform us of the decision taken at the first meeting of the committee choosing arms for Canada. The aggregate of provincial arms was completely rejected in favour of distinct arms which would include: “1) The Monarchical principle; 2) The French Regime and 3) Something Canadian such as the maple leaf.” [13] In the hierarchy of the committee, the maple leaf comes last. It is interesting that in a letter dated 8 June 1914, Pope enunciates the same principles for the arms of Canada but omits any Canadian content. [14] This opens the possibility that other members of the committee insisted on the inclusion of the maple leaf. The monarchical principle was emphasized by the composition mostly patterned on the arms of the United Kingdom and the insistence of the committee that the arms should be royal arms for Canada. The principles enunciated by the committee from the start of its deliberation were exactly what the composition of Canada’s coat of arms would become in the end (fig. 5).

It is certain that Pope did not want royal arms that would emphasize Canada at the expense of imperial content. This is no doubt the meaning of Mulveys statement in his letter to the editor of the magazine Rod and Gun in Canada quoted above “As your correspondent says, the Lion is not the representative of Canada except in so far as Canada is a part of the British Empire, and in this connection it was considered appropriate to have the Lion hold the Maple Leaf.”

Most of the components of Canada’s coat of arms reflect the country’s history as a colony of France and subsequently of Great-Britain. The crown had been placed spontaneously above the Dominion shields for some 50 years. It was normal that it be retained for the granted arms to highlight the fact that Canada is a constitutional monarchy. All the other components likewise have a historical link to Canada: the arms of the founding nations appearing on the shield and the flowers below the shield with the same significance, the Union Jack and banner of royal France which both flew on Canadian soil from early colonial days, the lion and unicorn which were part of the royal arms of the United Kingdom that dominated the Canadian scene for many years. Four components are Canadian: the sprig of maple in base of the shield, the red leaf in the paw of the lion, the colours in the mantling which became Canada’s colours and the motto which was proposed by Samuel Leonard Tilley, a Father of Confederation, to reflect the country’s geography.

The armorial bearings highlight Canada’s strong European roots with indications that it is becoming a country in its own right. Although Pope assuredly did not see it this way, the notion of royal arms for Canada is consistent with the assertion in the preamble to the Statute of Westminster of 1931 which gave the country its independence: “… inasmuch as the Crown is the symbol of the free association of the members of the British Commonwealth of Nations, and as they are united by a common allegiance to the Crown …” The fact that Canada’s arms paid homage to the country’s colonial past and the founding nations helped prepare Canadians to move on to something else for its flag, namely a red maple leaf as a unique symbol of the land and its people.

Fig. 5. The achievement of arms of Canada granted by proclamation of King George V on 21 November 1921. In 1994 Queen Elizabeth II approved the addition of the motto of the Order of Canada on a ring around the shield (see: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/arms-of-canada.html, figure 5). This illustration is from a souvenir plate by Adams (England) commemorating the 175th Anniversary Albion Lodge No. 2, A.F. & A.M., Quebec. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

The Rise of the Maple Leaf

In the nineteenth century when the phenomenon began, Canadians, particularly French Canadians, acknowledged both the maple tree and its leaf as their emblems. The first documented instance where the maple tree was designated as an emblem of Francophone Canada was in Le Canadien of 1806 where the rival newspaper, the English Mercury, was mocked in an epigram. The Society “Aide toi et le ciel t’aidera” (Help yourself, and heaven will help you) founded in 1834 evolved into the Saint-Jean-Baptiste Society which was formally incorporated in 1843. At its third annual meeting in 1836, its president, Denis-Benjamin Viger, stated that the maple tree was the emblem of the peuple canadien,” by which he meant French Canadians. At the same meeting, its former president, Ludger Duvernay, sang a song of his own composition describing the maple as a symbol of unity. In 1863 Sir John William Dawson, principal of McGill University, referred to the maple as the national tree of Canada (see above). In a 1889 poem called “L’érable” (The Maple), the Francophone poet William Chapman states that our ancestors (French Canadians) took the leaf of the tree as the emblem of their nationality, thus expressing a transition from the tree to the leaf. [15] The expression “Land of the Maple” referring to Canada appeared in the nineteenth century and became widespread among Anglophone Canadians in the early years of the twentieth century. [16] The maple was officially recognized as Canada’s national tree in 1996.

In matters of symbolism, a maple leaf is more powerful than a maple tree because it is simpler and simple things have more visual impact than complex ones in the world of emblems and heraldry. For instance, a ship wheel or train wheel is more symbolically evocative than a bulky ship or train. To make this concept even clearer, a cogwheel symbolizes industry better than a mill with many buildings and smoke stacks which may represent one type of industry, but not a multitude of industries as the cogwheel can. England is represented by a rose and not an entire rose bush, Scotland by a thistle flower and not an entire plant, and Ireland by a three-leaved shamrock and not by a complete clover plant. Heraldic trees are often simplified to include only the most salient features that make them more easily recognizable (figs. 6-11). In some armorial depictions, trees are unidentifiable. While some heraldic descriptions (blazons) specify tree species; some do not as in the arms granted to William and Simon McGillivray (see Appendix I). A symbolic figure always evokes something much larger than itself. To represent Canada, an artist could paint a large mural with types of inhabitants, scenery, resources, and industries, yet could not represent all aspects of the country as does a single maple leaf.

In the nineteenth century when the phenomenon began, Canadians, particularly French Canadians, acknowledged both the maple tree and its leaf as their emblems. The first documented instance where the maple tree was designated as an emblem of Francophone Canada was in Le Canadien of 1806 where the rival newspaper, the English Mercury, was mocked in an epigram. The Society “Aide toi et le ciel t’aidera” (Help yourself, and heaven will help you) founded in 1834 evolved into the Saint-Jean-Baptiste Society which was formally incorporated in 1843. At its third annual meeting in 1836, its president, Denis-Benjamin Viger, stated that the maple tree was the emblem of the peuple canadien,” by which he meant French Canadians. At the same meeting, its former president, Ludger Duvernay, sang a song of his own composition describing the maple as a symbol of unity. In 1863 Sir John William Dawson, principal of McGill University, referred to the maple as the national tree of Canada (see above). In a 1889 poem called “L’érable” (The Maple), the Francophone poet William Chapman states that our ancestors (French Canadians) took the leaf of the tree as the emblem of their nationality, thus expressing a transition from the tree to the leaf. [15] The expression “Land of the Maple” referring to Canada appeared in the nineteenth century and became widespread among Anglophone Canadians in the early years of the twentieth century. [16] The maple was officially recognized as Canada’s national tree in 1996.

In matters of symbolism, a maple leaf is more powerful than a maple tree because it is simpler and simple things have more visual impact than complex ones in the world of emblems and heraldry. For instance, a ship wheel or train wheel is more symbolically evocative than a bulky ship or train. To make this concept even clearer, a cogwheel symbolizes industry better than a mill with many buildings and smoke stacks which may represent one type of industry, but not a multitude of industries as the cogwheel can. England is represented by a rose and not an entire rose bush, Scotland by a thistle flower and not an entire plant, and Ireland by a three-leaved shamrock and not by a complete clover plant. Heraldic trees are often simplified to include only the most salient features that make them more easily recognizable (figs. 6-11). In some armorial depictions, trees are unidentifiable. While some heraldic descriptions (blazons) specify tree species; some do not as in the arms granted to William and Simon McGillivray (see Appendix I). A symbolic figure always evokes something much larger than itself. To represent Canada, an artist could paint a large mural with types of inhabitants, scenery, resources, and industries, yet could not represent all aspects of the country as does a single maple leaf.

|

Fig. 6. Oak with typical leaves and acorns

Fig. 9. Beech tree recognized by its leaves

|

Fig. 7. Grapevine identified by grape bunches, tendrils and leaves

Fig. 10. A linden tree with heart-shaped leaves |

Fig. 8. Olive tree with leaves and fruit Fig. 11. A stylized heraldic tree meant to represent a wild plum tree

|

Figures 6 to 11, the trees above, have been stylized to include only their most typical attributes. Illustrations from Pierre Joubert, Les lys et les lions, Les Presses de l’Île-de-France, 1947. The maple tree has also been stylized in this way; see the arms of Thomas Philip Buckley: http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=40&ProjectElementID=115.

During the nineteenth century, the maple leaf increasingly rose in popularity to become a virtual craze before the Great War. As I have already treated this question extensively, there is no need to revisit the subject here, see: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/land-of-the-maple.html and http: //heraldicscienceheraldique.com/ldquothe-maple-leaf-foreverrdquo-a-song-and-a-slogan--the-maple-leaf-forever--une-chanson-et-un-slogan.html. The beaver was still a respected symbol of Canada but was losing ground to the maple and its leaf. This was already evident in the 1863 comments of Sir John William Dawson who, four years before Confederation, expressed a distinct bias for the maple tree. The members of the committee, particularly Joseph Pope, were wary of emphasizing Canadian symbols at the expense of ties with the British Empire and the Monarchy. Still they wanted to include some Canadian content and the popularity of the maple leaf no doubt made their choice easier. In 1945, Col. Archer Fortescue Duguid spoke of the triumph of the maple leaf as a national symbol: “The selection of the maple leaf as the national symbol of Canada reflects the transition from the Land of the Beaver to the Land of the Maple …” [17] The adoption of the maple leaf was by popular consent and frequent association with Canadian emblems such as on the colours of the 100th Prince of Wales Royal Canadian Regiment (1859), the armorial shields of Ontario (1868), Quebec (1868), and Canada (1921). In its 1964 booklet entitled The Arms of Canada, the Department of the Secretary of State describes the sprig of maple in base of Canada’s shield as “the emblem of Canada” which is a semi-official recognition of the leaf’s national status. The single maple leaf unequivocally rose to the rank of national emblem when it appeared in centre of Canada’s national flag in 1965.

Summary

1) Because of its commercial value, and particularly its pelt, the beaver was considered an emblem of Canada very early in the history of the country.

2) The beaver is also a suitable emblem for Canada because of its admirable qualities that reflect comparable traits in humans: hard work, exceptional skills, team spirit, care of family, strong self-preservation instinct, etc.

3) Negative aspects of the beaver reside in the fact that it is a rodent like the rat and is viewed as somewhat dull in comparison with the strong and courageous lion and the eagle that soars to great heights. This was quoted as the main reason why the arms committee excluded the beaver from Canada’s coat of arms.

4) The beaver has a distinct profile and lends itself well to caricature, but unlike the lion and eagle which have been stylized for centuries in heraldic art, artists are still searching for the best way to stylize the beaver so as to give it the poise and dignity favoured by heraldic art.

5) The committee wanted arms that would emphasize the monarchial principle and links to the British Empire with limited Canadian content.

6) The rise in popularity of the maple leaf throughout the nineteenth century and in the first quarter of the twentieth century coupled with a perceptible decline in the popularity of the beaver made it easier to include the maple leaf instead of the beaver in Canada’s coat of arms.

1) Because of its commercial value, and particularly its pelt, the beaver was considered an emblem of Canada very early in the history of the country.

2) The beaver is also a suitable emblem for Canada because of its admirable qualities that reflect comparable traits in humans: hard work, exceptional skills, team spirit, care of family, strong self-preservation instinct, etc.

3) Negative aspects of the beaver reside in the fact that it is a rodent like the rat and is viewed as somewhat dull in comparison with the strong and courageous lion and the eagle that soars to great heights. This was quoted as the main reason why the arms committee excluded the beaver from Canada’s coat of arms.

4) The beaver has a distinct profile and lends itself well to caricature, but unlike the lion and eagle which have been stylized for centuries in heraldic art, artists are still searching for the best way to stylize the beaver so as to give it the poise and dignity favoured by heraldic art.

5) The committee wanted arms that would emphasize the monarchial principle and links to the British Empire with limited Canadian content.

6) The rise in popularity of the maple leaf throughout the nineteenth century and in the first quarter of the twentieth century coupled with a perceptible decline in the popularity of the beaver made it easier to include the maple leaf instead of the beaver in Canada’s coat of arms.

Notes

[1] George M. Grant, Ocean to Ocean, (Toronto: James Campbell, 1873), pp. 224-25.

[2] Ruben Gold Thwaites, New Voyages to North America by Baron de Lahontan, Reprinted from the English Edition of 1703, vol. 1 (Chicago: McClurg & Co., 1905), pp. 171-72.

[3] C. A. Walckenaër, Œuvres complètes de Jean de la Fontaine avec des notes et une nouvelle notice sur sa vie (Paris, Lefèvre, 1835), p. 95.

[4] “Annual University Lecture, Delivered Nov. 27, 1863. Subject: ‘Duties of Educated Young Men in British America.’ By J.W. Dawson, Principal of McGill University, Montreal” printed as a report by the newspaper Montreal Daily Witness, p. 2. Many authors who have quoted Dawson refer to the beaver only without mentioning his favorable comments regarding the maple.

[5] Elizabeth Collard, Nineteenth-Century Pottery and Porcelain in Canada, 2nd ed. (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1984), pp. 223-24.

[6] Charles R. Tuttle, Tuttle's Popular History of the Dominion of Canada, vol.1 (Montreal & Boston: D. Downie & Co. / Tuttle and Downie, 1877). The portraits precede the title page. The book is available online: https://books.google.ca/books?id=qWBBAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA394&lpg=PA394&dq=Tuttle+history+of+the+Dominion&source=bl&ots=bnp-Pcn37_&sig=odt9JI97JH2EynW3EztIUOCyn68&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwifktzAh5zUAhUB5IMKHfrgA_8Q6AEIRjAG#v=onepage&q=Tuttle%20history%20of%20the%20Dominion&f=false.

[7] Library and Archives Canada, RG 6, A1, vol. 210, file 1156, part 4, p. 288, The Editor of Rod and Gun in Canada to the Secretary of State, 28 October 1922.

[8] Ibid., p. 287, Mulvey to Editor of Rod and Gun in Canada, 30 October 1922.

[9] Conrad Swan, “The Beaver and the Maple Leaf in Heraldry” in The Coat of Arms, 10, no. 75 (July 1968), p. 105.

[10] Library and Archives Canada, MG 30, E1, 86, vol. 20, no. 231, Pope to Smith, 13 February 1908. See also ibid., vol. 19, no. 120, Pope to Pottinger, 25 January 1907.

[11] Library and Archives Canada, RG 6, A1, vol. 210, file 1156, part 3, p. 310, Pope to Mulvey, 4 November 1921.

[12] See Pope’s biography by P.B. Waite in Dictionary of Canadian Biography online: http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pope_joseph_15E.html.

[13] Maurice Pope ed., Public Servant: the Memoirs of Sir Joseph Pope (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1960), pp. 282-83.

[14] His letter is quoted in chapter 3 of my work Canada’s Coat of Arms (with note 67, seventh paragraph after figure 16): http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/chapter-3-the-dominion-shield.html.

[15] Auguste Vachon, Canada’s Coat of Arms: Defining a Country within an Empire, chapter 2: “The Beaver and Maple Leaf” — http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/chapter-2-the-beaver-and-maple-leaf.html.

[16] Idem, “Land of the Maple” — http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/land-of-the-maple.html.

[17] Quoted in John Ross Matheson, Canada’s Flag: a Search for a Country (Belleville [Ontario]: Mika Publishing, 1986), p. 51.