Chapter VI

AN AUXILIARY SCIENCE

This is the second chapter in the heraldic trilogy: art, science, symbol. By the very fact that it has a precise structure, a number of rules, a vocabulary to describe imagery, and more or less complex modes of inheritance, heraldry was given the status of a science. What has been less explored is its role as an auxiliary science to other disciplines. Most students following a course on historical methodology are told that heraldry is an auxiliary science to history. I remember one of my professors chuckling rather ironically when heraldry came up and dismissing the whole subject as being of little relevance. Frankly I believe he had practically no idea as to how heraldry could be used as historical documentation or in solving historical problems.

Therefore, the aim of this chapter is to demonstrate that armorial emblems constitute in themselves historical records and are a most helpful tool for dating, identifying and authenticating documents and artefacts. This makes heraldry an essential aid to many other sciences such as genealogy, museology, archaeology, sigillography (science of seals), numismatics (coins and medals), vexillology (science of flags) and diplomatics (analysis of old documents for dating and authenticating). It also records family alliances that can be invaluable to the historian and genealogist. It has often been referred to as the garden of history, in other words, the place where one can glean the most interesting historical data in condensed form.

In 1967 I had prepared a small display for directors of the Heraldry Society of Canada who were meeting at the National Archives of Canada. Some directors objected that I was showing them several heraldic items devoid of any official status. From an historian’s point of view, this is not a tenable position. Both freely adopted and official heraldry constitute important historical documents as we shall see.

1. Heraldry as a Pictorial Document

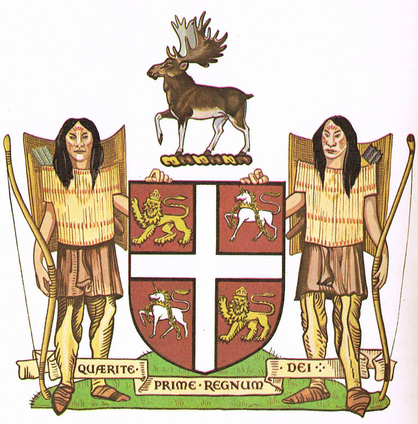

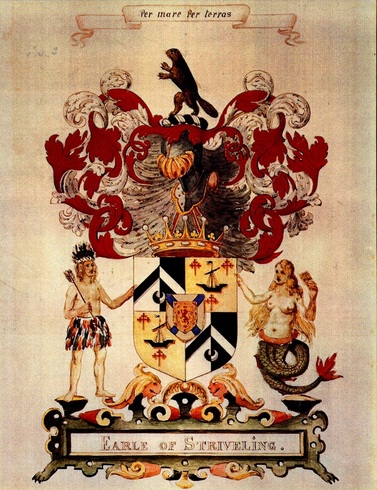

A specialist of material history will find within coats of arms depictions of tools, weapons, costumes and architectural structures such as fortifications and bridges, which are of real documentary value. The value of coats of arms as documents is not as far-reaching in North America as it is in Europe because heraldry was introduced here much later, and there are often better pictorial sources than what we find on coats of arms. Yet even here, there exists examples of arms containing essential historical data. The supporters of the shield of Newfoundland granted by Charles I in 1637 are the only known examples of the war costume of the now extinct Beothuk Indians. It is not a fanciful depiction since pictorial and written sources confirm that other tribes such as the Hurons and Iroquois wore similar shields and armour made of mats of wooden sticks bound together (fig. 1). [1] Heraldic imagery can also have an ethnographic dimension. Many of the First Nation figures made to support shields in seventeenth and into the eighteenth centuries were stereotyped figures in feathered skirt and headdress. Such supporters were granted to Canadian individuals and corporate bodies even though the attire was not adapted to northern climates. The outlandish feathered kilt and headdress became conventional in a similar way that other false stereotypes become the norm (figs. 1-2). See also: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/lrsquoameacuterindien-steacutereacuteotypeacute-en-heacuteraldique-canadienne--son-eacutevolution-en-regard-de-lrsquoimage-imprimeacutee.html (has an English summary).

|

Fig. 1 Arms of Newfoundland, granted in 1637. Studies have demonstrated that the war costume of the two Beothuk Indian supporters is realistic. |

Fig. 2 Arms of Sir William Alexander, Viscount of Stirling in 1630, Viscount of Canada and Earl of Stirling in 1633. His left supporter is a stereotyped Amerindian in a feather skirt and headdress, typical of the period. Library and Archives Canada.

|

The arms granted to William and Simon McGillivray by the Kings of Arms of England in 1823 contain all the elements of the arms attributed to the North West Company, which were never made official. Both arms display in chief (upper part of the shield) a North West canoe paddled by Amerindians with a man in European dress in the centre, probably William McGillivray himself as head of the company. At the stern of the canoe, is flown the red flag of the North West Company bearing the letters NW in gold script. These coats of arms provide the only known evidence we have of the canoe flag of the North West Company and they contain as well interesting depictions of a North West canoe (figs. 3-4). The granting document itself reveals considerable data regarding the two brothers and the history of the Company. [2]

The same North West Company imagery is present on the medal of the Beaver Club founded in Montreal in 1785 and restricted to fur trade veterans of the Upper Lakes, les pays d’en haut. On the medal’s reverse, we see a North West canoe with the motto “Fortitude in Distress” and, on the obverse, the North West Company beaver gnawing at a tree with the motto “Industry and Perseverance”. A seal engraved with a beaver chewing into a tree, the motto perseverance on a scroll above and the initials NW Co below was handed down by Dr. John McLouglin, a wintering partner of the North West Company. [3] The seal may have been used, although we still have to find its impression on documents. [4] The canoe and its flag as well as the crest in the achievement of arms granted to Thunder Bay by the English Kings of Arms in 1970 were derived from the McGillivray grant (fig. 5).

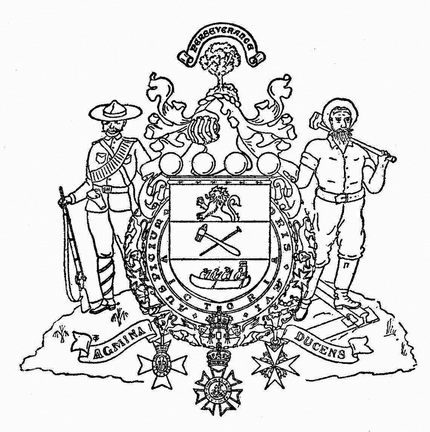

The arms of Donald Alexander Smith, 1st Baron Strathcona, contain two clear allusions to the North West Company, although some of the terminology used to describe them is not especially North American. The crest (above the shield) is a beaver “eating into a maple tree” with the motto “Perseverance” on a scroll above. [5] In base of the shield is featured a North West canoe “with four men rowing” and flying the North West canoe flag at the stern. Strathcona’s arms also contain two clear allusions to his activities in railroad building. The right supporter of his shield is a navvy with a hammer on his shoulder, standing on a railway sleeper with a stretch of rail nailing on top. In the centre of his shield, a hammer and nail in saltire represent the Last Spike he himself drove down when the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1885. The left supporter of his arms is a rifleman of the Regiment of Strathcona’s Horse in uniform, alluding to the regiment of 500 mounted riflemen, which Smith created and maintained himself to fight in the South African War (fig. 6).

The arms of Donald Alexander Smith, 1st Baron Strathcona, contain two clear allusions to the North West Company, although some of the terminology used to describe them is not especially North American. The crest (above the shield) is a beaver “eating into a maple tree” with the motto “Perseverance” on a scroll above. [5] In base of the shield is featured a North West canoe “with four men rowing” and flying the North West canoe flag at the stern. Strathcona’s arms also contain two clear allusions to his activities in railroad building. The right supporter of his shield is a navvy with a hammer on his shoulder, standing on a railway sleeper with a stretch of rail nailing on top. In the centre of his shield, a hammer and nail in saltire represent the Last Spike he himself drove down when the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1885. The left supporter of his arms is a rifleman of the Regiment of Strathcona’s Horse in uniform, alluding to the regiment of 500 mounted riflemen, which Smith created and maintained himself to fight in the South African War (fig. 6).

As the garden where the most interesting flowers of history are picked, coats of arms and flags can be used to great advantage as teaching tools. In fact, from the traditional point of view, the history of Canada began with heraldry. To mark the discovery of this new land, Cartier raised a large cross at Gaspé Harbour on July 24, 1534 and later a second cross at Stadacona (today the City of Quebec) both bearing the royal arms of King Francis I of France, namely three gold fleurs-de-lis on a blue shield. Both crosses bore an inscription wishing the king a long life and reign. On his second voyage in 1535, Cartier’s ships were named Grande Hermine, Petite Hermine and Émerillon meaning the large ermine, the small ermine and the merlin (a kind of falcon). Ermine is a direct reference to the shield of arms of Brittany that is strewn with ermine spots and to those of Saint-Malo, Cartier’s hometown that display a running ermine wearing a cloak also strewn with ermine spots. [6] The merlin appears in a few examples of Breton heraldry and the actual bird is found in both Brittany and all across Canada.

Arms often accompany the portrait of a historical figure. This is most fitting since arms may be considered a sort of portrait of one’s personal history and beliefs. In this sense, they can provide useful insight to a biographer. A fine example of biographical content is found in the arms of the late Lieutenant-Commander Alan Brookman Beddoe, founder and 1st president of the Heraldry Society of Canada (fig. 7). He had gone overseas in the fall of 1914 with the first contingent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force whose members were called “Red Chevrons.” This is alluded to by the red chevron as the main symbol on his white shield, red and white also being the colours of Canada. The chief (upper third part of the shield) is blue and divided by a wavy line symbolizing water in reference to some 180 badges he designed for the Royal Canadian Navy. On the blue chief, a gold lion passant (walking by) holds a white shield displaying a red maple leaf. The gold lion is derived from the royal arms of England, as a reminder that heraldry is a royal prerogative, while the maple leaf on the shield stands for his tireless efforts to promote sound heraldry in Canada. The gold boar’s head in the crest refers to a device freely used in the past by some members of his family. Here it is part of an official grant, and it is decked with a red maple leaf to make it an unquestionably Canadian symbol.

The Beddoe arms contain a number of allusions to the past, others referring to his achievements, and some to his hope that heraldic art and science to which he devoted most of his life will survive his earthly existence. The motto Memini (I remember) alludes to his love and respect of traditional values and to his work as the artist responsible for creating the “Book of Remembrance” housed in the Memorial Chamber of the Peace Tower. His motto is in fact the Latin equivalent of that of the province of Quebec “Je me souviens”, although there is no direct relationship between the two. The question “I remember what?” has often been asked regarding Québec’s motto, as if it were incomplete. The answer to this is not difficult for those who are attached to their past and tradition. A similar motto Ne obliviscaris (Do not forget) is that of clan Campbell and seems perfectly understood and accepted without asking “Do not forget what?” Alan Beddoe viewed heraldry as an important instrument for promoting Canadian unity. He understood and respected the fact that the same ideas, such as the mottos just mentioned, and the lion and fleur-de-lis for that matter, are found in several heraldic traditions and can become a uniting rather than a divisive force.

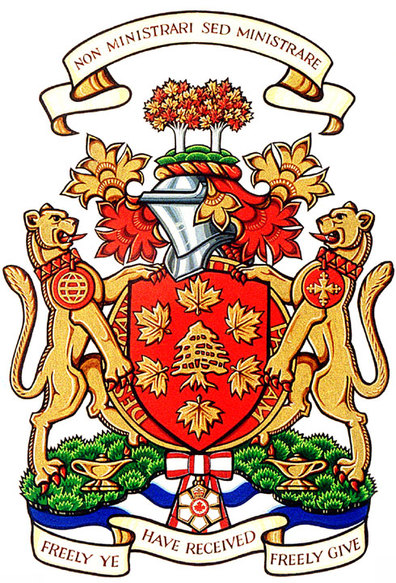

So many personal arms are reminders that we are largely a land of immigration expressed in heraldry by allusions to ancestral roots and symbols of the newly adopted land. The arms assigned to Dr. Helen Kathleen Mussallem display the cedar of Lebanon on the shield to honour her Lebanese heritage while the six maple leaves represent her brothers and sisters and herself, all Canadian-born (fig. 8). The two maples in the crest allude to her parents as founders of the Canadian branch of the family. The cougars, animals of grace, spirit and determination, embody personal qualities and are a reference to British Columbia, her place of birth. The medallion worn by the cougar on the right displays a Greek cross joined with the cross of Antioch alluding to her parents’ Christian denominations. The globe medallion worn by the cougar on the left symbolizes the international character of Dr. Mussallem’s professional and volunteer service as a special advisor to national and international health organizations. The two lamps on the compartment on which the cougars stand refer to her nursing career as does the Latin motto above the crest, which means “Not to be ministered unto but to minister.”

Arms often accompany the portrait of a historical figure. This is most fitting since arms may be considered a sort of portrait of one’s personal history and beliefs. In this sense, they can provide useful insight to a biographer. A fine example of biographical content is found in the arms of the late Lieutenant-Commander Alan Brookman Beddoe, founder and 1st president of the Heraldry Society of Canada (fig. 7). He had gone overseas in the fall of 1914 with the first contingent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force whose members were called “Red Chevrons.” This is alluded to by the red chevron as the main symbol on his white shield, red and white also being the colours of Canada. The chief (upper third part of the shield) is blue and divided by a wavy line symbolizing water in reference to some 180 badges he designed for the Royal Canadian Navy. On the blue chief, a gold lion passant (walking by) holds a white shield displaying a red maple leaf. The gold lion is derived from the royal arms of England, as a reminder that heraldry is a royal prerogative, while the maple leaf on the shield stands for his tireless efforts to promote sound heraldry in Canada. The gold boar’s head in the crest refers to a device freely used in the past by some members of his family. Here it is part of an official grant, and it is decked with a red maple leaf to make it an unquestionably Canadian symbol.

The Beddoe arms contain a number of allusions to the past, others referring to his achievements, and some to his hope that heraldic art and science to which he devoted most of his life will survive his earthly existence. The motto Memini (I remember) alludes to his love and respect of traditional values and to his work as the artist responsible for creating the “Book of Remembrance” housed in the Memorial Chamber of the Peace Tower. His motto is in fact the Latin equivalent of that of the province of Quebec “Je me souviens”, although there is no direct relationship between the two. The question “I remember what?” has often been asked regarding Québec’s motto, as if it were incomplete. The answer to this is not difficult for those who are attached to their past and tradition. A similar motto Ne obliviscaris (Do not forget) is that of clan Campbell and seems perfectly understood and accepted without asking “Do not forget what?” Alan Beddoe viewed heraldry as an important instrument for promoting Canadian unity. He understood and respected the fact that the same ideas, such as the mottos just mentioned, and the lion and fleur-de-lis for that matter, are found in several heraldic traditions and can become a uniting rather than a divisive force.

So many personal arms are reminders that we are largely a land of immigration expressed in heraldry by allusions to ancestral roots and symbols of the newly adopted land. The arms assigned to Dr. Helen Kathleen Mussallem display the cedar of Lebanon on the shield to honour her Lebanese heritage while the six maple leaves represent her brothers and sisters and herself, all Canadian-born (fig. 8). The two maples in the crest allude to her parents as founders of the Canadian branch of the family. The cougars, animals of grace, spirit and determination, embody personal qualities and are a reference to British Columbia, her place of birth. The medallion worn by the cougar on the right displays a Greek cross joined with the cross of Antioch alluding to her parents’ Christian denominations. The globe medallion worn by the cougar on the left symbolizes the international character of Dr. Mussallem’s professional and volunteer service as a special advisor to national and international health organizations. The two lamps on the compartment on which the cougars stand refer to her nursing career as does the Latin motto above the crest, which means “Not to be ministered unto but to minister.”

|

Fig. 7 Arms granted to Alan B. Beddoe by the Kings of Arms of England 1960. From the dust jacket of Beddoe’s Canadian Heraldry.

|

Fig. 8 Arms granted to Helen Kathleen Mussallem by the Chief Herald of Canada (Ottawa, Ontario) 5 March 1996 (vol. III, p. 78). Reproduced by permission of the Canadian Heraldic Authority of Canada © Her Majesty in Right of Canada. See: http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=595&ShowAll=1

|

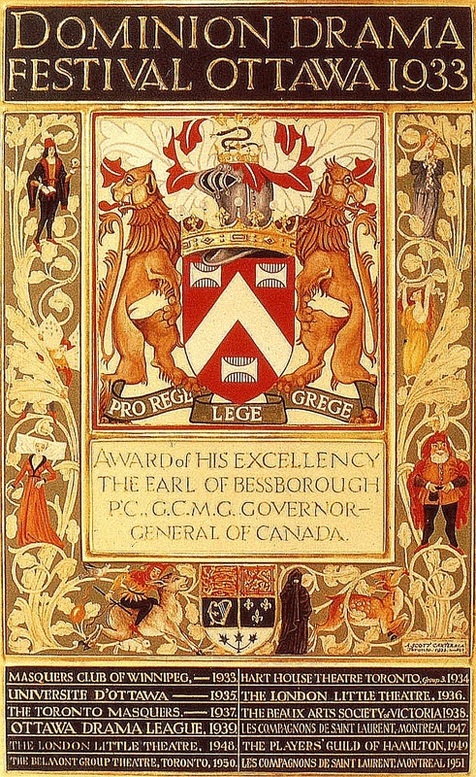

The arms of the Governors General of Canada are displayed on their seals and medals and sometimes on trophies such as the Minto Cup donated in 1901 by the 4th Earl of Minto to be presented to the winners of the Canadian Junior Lacrosse Championship. In the past, governors general have extended their patronage to businesses and cultural institutions by presenting them with a plaque or a certificate illustrated with their arms in colour (fig. 9). For the Canadian governors general since 1952, the symbolism of their arms is well known and could be used to illustrate their personal history, achievements and aspirations.

Fig. 9 Plaque by Alexander Scott Carter in the collections of the Canadian Museum of History. The recipients of this plaque awarded by Governor General Bessborough are: Masquers Club of Winnipeg, 1933; Hart House Theatre Toronto, Group 3, 1934; Université d’Ottawa, 1935; The London Little Theatre, 1936; The Toronto Masquers, 1937; The Beaux Arts Society of Victoria, 1938; Ottawa Drama League, 1939; Les Compagnons de Saint Laurent, Montreal, 1947; The London Little Theatre, 1948; The Players’ Guild of Hamilton, 1949; The Belmont Group Theatre, Toronto, 1950; Les Compagnons de Saint Laurent, Montreal, 1951.

Heraldry as a learning tool provides focus and functions as an aide-mémoire as students discover the historical significance of various symbols. It plays upon their imagination as they leap mentally from a symbol to the reality it represents. Although the Canadian Heraldic Authority’s work is ongoing, it would even now be possible to recreate a history of Canada evolving from a colony to a nation based on the symbolism found in coats of arms and flags: an interesting and challenging project for someone to take on.

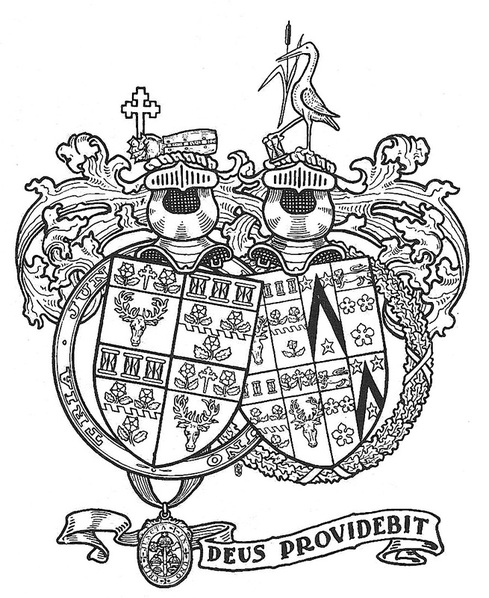

Heraldry can prove indispensable in tracing family alliances. Finding the arms of a family within a shield containing dozens or even hundreds of quarterings (divisions containing individual arms) could lead to the discovery of numerous unsuspected family alliances. The arms of individual members of a Scottish clan will usually contain elements that echo the arms of the chief. As a sign of allegiance, members of the clan are allowed to use a badge consisting of the crest of the chief enclosed in a strap with a buckle bearing the chief’s motto.

Some mottos are a variation on the same theme. Usually both the crest and motto of members of the Chattan Confederation of Clans refer to a feline creature. The cat or demi-cat, domestic or wild, is represented in the crest of various clans and septs with the claws of the forepaws menacingly extended. The variations on the motto are impressive: “Touch not the cat(t) but (bot) a glove, Touch not the cat without a glove, Touch not a cat bot a targe (type of shield), Touch not this cat, Not this but a glove, Touch not gloveless, Touch not”. One Latin variation “Qui me tanget poenitebit” (Who touches me will be sorry) contains the idea of punishment for intrusive action. All these mottos―the variations seem endless― in combination with a feline crest point to one alliance, to one big family whose members are dispersed in many countries, and whose chiefs have resided on several continents (figs. 4, 10, 11 and the site http://www.clan-macpherson.org/canada/heraldry.html).

Heraldry can prove indispensable in tracing family alliances. Finding the arms of a family within a shield containing dozens or even hundreds of quarterings (divisions containing individual arms) could lead to the discovery of numerous unsuspected family alliances. The arms of individual members of a Scottish clan will usually contain elements that echo the arms of the chief. As a sign of allegiance, members of the clan are allowed to use a badge consisting of the crest of the chief enclosed in a strap with a buckle bearing the chief’s motto.

Some mottos are a variation on the same theme. Usually both the crest and motto of members of the Chattan Confederation of Clans refer to a feline creature. The cat or demi-cat, domestic or wild, is represented in the crest of various clans and septs with the claws of the forepaws menacingly extended. The variations on the motto are impressive: “Touch not the cat(t) but (bot) a glove, Touch not the cat without a glove, Touch not a cat bot a targe (type of shield), Touch not this cat, Not this but a glove, Touch not gloveless, Touch not”. One Latin variation “Qui me tanget poenitebit” (Who touches me will be sorry) contains the idea of punishment for intrusive action. All these mottos―the variations seem endless― in combination with a feline crest point to one alliance, to one big family whose members are dispersed in many countries, and whose chiefs have resided on several continents (figs. 4, 10, 11 and the site http://www.clan-macpherson.org/canada/heraldry.html).

|

Fig. 10 Arms of the Honourable Justice Angus Alexander Cattanach. “Touch not” is a variation on the motto of Clan Chattan “Touch not the catt but a glove.” From Beddoe’s Canadian Heraldry, p. 126.

|

Fig. 11 Arms granted to William Macpherson by the Chief Herald of Canada 15 May 2012 (vol. VI, p. 138). “Dare not touch the ungloved cat” is a variation on the motto of Clan Chattan “Touch not the catt but a glove.” Reproduced by permission of the Canadian Heraldic Authority of Canada © Her Majesty in Right of Canada. See: http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=2320.

|

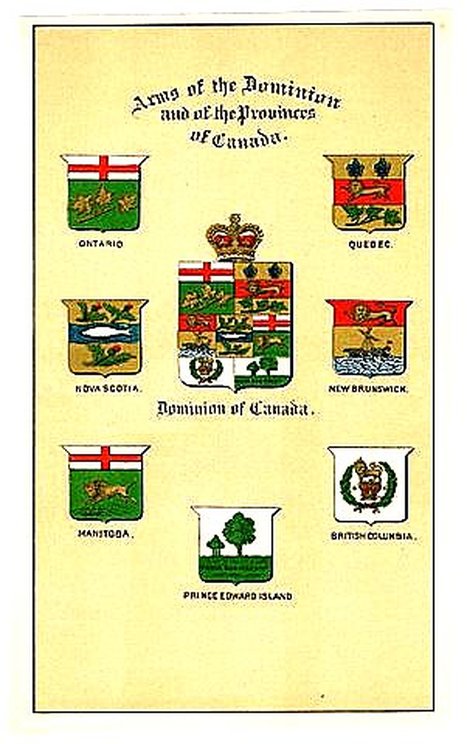

2. Canada’s Arms, a Shorthand of the Country’s History Since Confederation

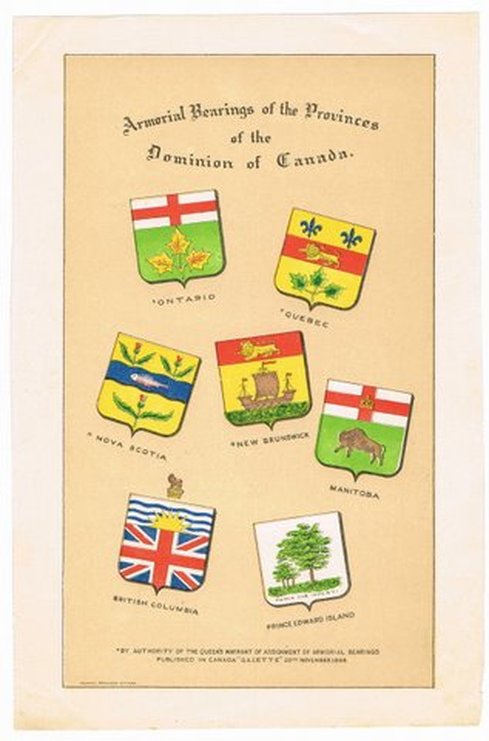

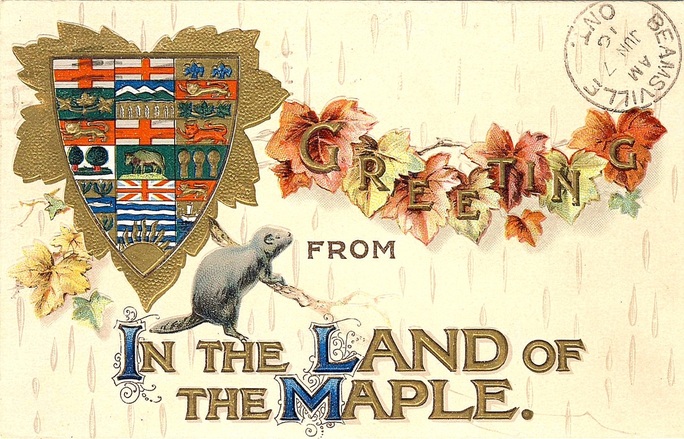

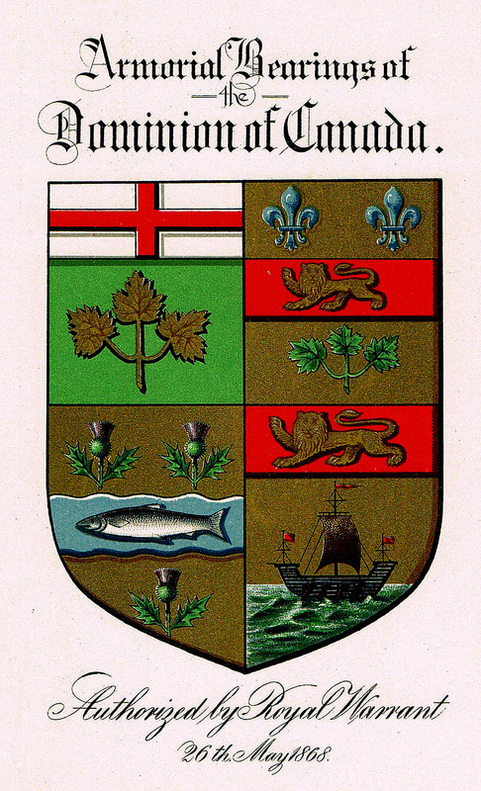

The arms of Canada have undergone many changes that came about at known dates or during periods that can only be approximated. At Confederation the united provinces of Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick were each granted a shield of arms. The royal warrant of Queen Victoria specified “... that the said United Provinces of Canada being one Dominion under the name of Canada shall upon all occasion that may be required use a Common Seal to be called the Great Seal of Canada which said Seal shall be composed of the Arms of the said Four Provinces Quarterly...”

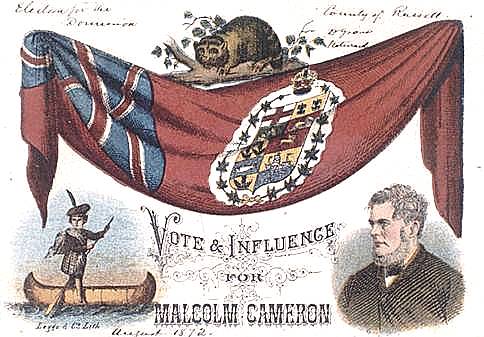

An article in the Canadian Illustrated News of 1871 declared that the quartered shield constituted the arms of Canada although its use was clearly specified for a common seal. [7] The article contained illustrations of this four-province shield within a wreath of maple leaves and with a crown added on top. This augmented device appeared in the fly of the Red Ensign, the Blue Ensign and in centre of the White Ensign, which it erroneously declared to be the governor general’s flag. The actual flag authorized for the governor general in 1870 was the Union Jack with the four-province shield in the centre. The four-province shield within maple leaves topped by the crown was still in use in August 1872 as demonstrated by a poster entitled “Vote and Influence for Malcolm Cameron” (fig. 12). The arms are in the fly of the Red Ensign, on top of which is an impressive beaver on a log with leaved branches. These early arms were generally depicted in a more or less awkward style.

The arms of Canada have undergone many changes that came about at known dates or during periods that can only be approximated. At Confederation the united provinces of Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick were each granted a shield of arms. The royal warrant of Queen Victoria specified “... that the said United Provinces of Canada being one Dominion under the name of Canada shall upon all occasion that may be required use a Common Seal to be called the Great Seal of Canada which said Seal shall be composed of the Arms of the said Four Provinces Quarterly...”

An article in the Canadian Illustrated News of 1871 declared that the quartered shield constituted the arms of Canada although its use was clearly specified for a common seal. [7] The article contained illustrations of this four-province shield within a wreath of maple leaves and with a crown added on top. This augmented device appeared in the fly of the Red Ensign, the Blue Ensign and in centre of the White Ensign, which it erroneously declared to be the governor general’s flag. The actual flag authorized for the governor general in 1870 was the Union Jack with the four-province shield in the centre. The four-province shield within maple leaves topped by the crown was still in use in August 1872 as demonstrated by a poster entitled “Vote and Influence for Malcolm Cameron” (fig. 12). The arms are in the fly of the Red Ensign, on top of which is an impressive beaver on a log with leaved branches. These early arms were generally depicted in a more or less awkward style.

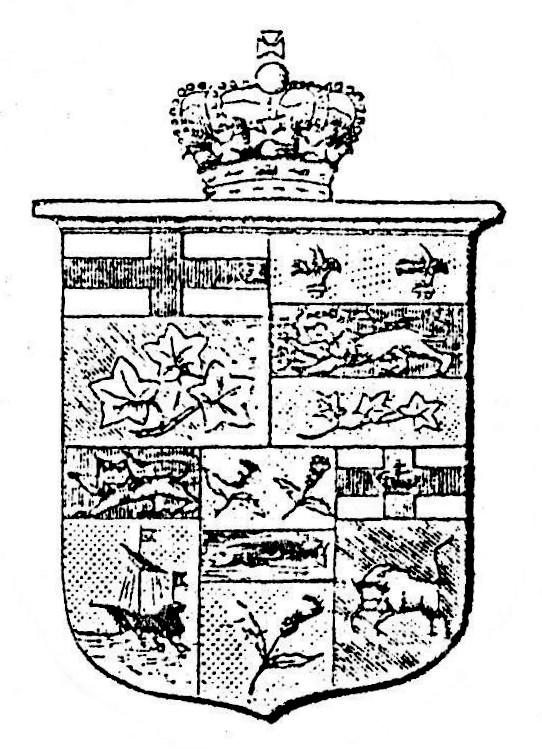

Fig. 12 Election poster 1872, Library and Archives Canada, neg. C -120987.

Over the years, provincial and territorial emblems were added to the Dominion shield with the royal crown on top of the shield, a beaver on a branch or log below, the whole within branches of maple, sometimes maple on one side and oak on the other. In 1873, and possibly slightly before, imagery inspired by the 1870 seal of Manitoba was added to the Dominion aggregate, namely, a red St. George Cross bearing the royal crown in chief of the shield and a charging bison in base, although the bison on the actual seal was simply standing. An example of these augmented arms is seen, perhaps for the first time, on the first page of L’opinion publique, of 2 January 1873. A little later, the same arms appeared in the tennis court and ballroom of Rideau Hall, the latter being opened in March of 1873 (fig. 13). Other examples of the five-province shield are seen on an 1876 bird’s eye view of Ottawa and on the front page of an 1877 Canadian Illustrated News. [8]

Fig. 13 The five-province arms of the Dominion as they appeared in the tennis court and ballroom of Rideau Hall, the latter being opened in March of 1873. The illustration is from the article “State and Society in Ottawa” in Lippincott’s Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, June 1879, p. 656.

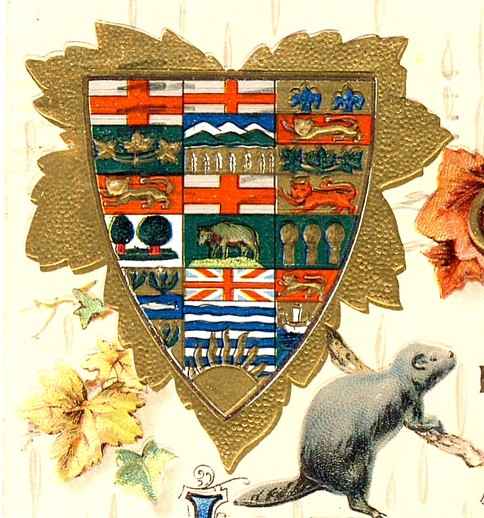

By 1876 a further augmented version of the composite arms began replacing the five-province shield as evidenced on the Dominion of Canada Exhibition Medal of that year. [9] This new version, which continued in use until ca. 1910, was composed of the seals of Manitoba, British Columbia and Prince Edward Island added to the four original provinces. The seal of British Columbia featured a crowned lion set upon the royal crown, flanked by the letters B.C., all within a branch of laurel on the left and a branch of oak on the right. The seal of Prince Edward Island contained a large Oak with a cluster of three smaller ones on an Island and the motto of today, Parva sub ingenti, (The small under the protection of the great) inscribed below. On the Dominion shield, the tree smaller oaks often became a single one. On the majority of these depictions, the crown on the head of the lion in the seal of British Columbia is absent, and the crown on the red cross in the seal of Manitoba is likewise missing (figs. 14-16).

Fig.14 The Dominion shield and individual arms and devices, used from ca. 1876 to ca. 1905. Print, property of A. & P. Vachon.

Fig. 15 Dominion shield with four provincial arms and three provincial seals, ca. 1900. On plate with Gemma mark, by Schmidt & Co., Altrohlau, Austria. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

In 1895 Reverend Arthur John Beanlands of Victoria designed arms for the new seal of British Columbia that were made up of the Union Jack in base of the shield and a sun rising in front of water in chief (the reverse of today’s version, fig. 16). From 1901 to 1903, a heraldic enthusiast named Edward Marion Chadwick designed three new devices. As these were represented variously coloured, they are here described rather summarily. For Prince Edward Island, a branch of oak on top of the shield and a branch of maple below; for the Yukon, a gold lion in chief and, in base, three pointed triangles decked with gold roundels representing gold bearing mountains; for Northwest Territories, a white polar bear on a chequered white and blue background in chief and four gold wheat sheaves in base (fig. 17).

Fig. 16 Arms and devices of provinces from 1895 to ca. 1905. Note the shield of British Columbia (bottom left) designed by Reverend Arthur John Beanlands in 1895. Print, property of A. & P. Vachon.

As a result of these new designs, a new composite Dominion shield appeared in 1903, although the previous aggregate continued in use for a few years. This version topped by the royal crown, enclosed in branches of maple, and with a beaver on a log underneath the shield, was very popular on souvenirs particularly on ceramics, but it did not last very long (fig. 17).

Fig. 17 Dominion shield with four provincial arms, two provincial seals and three Chadwick designs, ca. 1905. The aggregate comprises: 1st row, Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia (granted arms); 2nd row, New Brunswick (granted arms), British Columbia (Beanlands), Prince Edward Island (Chadwick); 3rd row, Northwest Territories (Chadwick), Yukon (Chadwick), Manitoba (seal). On a plate with Gemma mark, by Schmidt & Co., Altrohlau, Austria. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

In 1905 Manitoba and Prince Edward Island were granted official arms followed by British Columbia and Saskatchewan in 1906. This version did not include Alberta, which was granted arms in 1907 (figs. 17-19). A revised version followed that contained only the nine provinces of that time in various arrangements (figs. 20-21). [10]

Fig. 18 Arms of Dominion representing eight provinces and Chadwick’s design for the Yukon, Alberta missing, on 1908 plate by Wedgwood, England. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

Fig. 19 Eight granted arms and Yukon in fly of the Red Ensign, on a 1909 plate by Wedgwood, England. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

Fig. 20 Postcard of the B. B. London Series, printed in Germany, property of A. & P. Vachon. Although not of the best taste, this postcard reflects a strong national sentiment, at least for Anglophone Canadians.

Fig. 21 A nine-province shield with only granted arms placed on a maple leaf accompanied by a beaver. Detail of fig. 20. The quarters are as follows: 1st row, Ontario, Alberta, Quebec; 2nd row, Prince Edward Island, Manitoba, Saskatchewan; 3rd row, Nova Scotia, British Columbia, New Brunswick.

Some ten-province shields appeared with the strangest supporters such as the god Mercury, on the right, displaying bare breast which rival admirably those of the goddess Ceres on the left, displayed on the Dominion Express Building, St. Jacques Street, Montreal, see: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Dominion_Express_Building#/media/File:Dominion_Express_04.jpg and https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a5/Dominion_Express_06.jpg. One strange anachronism is a ten-province shield found on the former Dominion Bank (later Toronto Dominion Bank) at the corner of Sparks and Bank streets in Ottawa. It displays a beaver as crest, two foxes as supporters and a Canada goose with wings expanded below, see: http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_u2WcNSWdwE8/SrLY7TZzZVI/AAAAAAAABbE/I11YegD-ItI/s1600-h/P6300015.JPG. This version is highly anachronistic since the façade dates from 1949, the year Newfoundland joined Confederation, and yet the architect chose to include the ten provinces rather than the proper arms granted to Canada in 1921. [11]

Around 1900 Sir Joseph Pope, then Under Secretary of State, began preaching that the arms assigned to Canada in 1868 were composed of only the four original provinces, and he published a colour print in 1904 to make his point. His print was entitled, “Arms of the Dominion of Canada”, although the 1868 royal warrant had assigned the arms for use as a Dominion seal (fig. 22). Pope’s intentions were to eliminate the composite shields which he called “heraldic monstrosities”. His campaign was only partially successful, but shields with only the four provinces appeared on a number of Canadian Ensigns and post cards at that time. These later shields are distinguished from those just after Confederation by their much clearer and precise heraldic style. Some of them were still topped by the crown, but without all the trappings of the earlier ones (fig. 23). Sometimes, antique dealers date souvenirs with this shield as just following Confederation because they display only four provincial arms, but they are, in fact, from around 1904. So Caveat emptor! Buyer beware!

Around 1900 Sir Joseph Pope, then Under Secretary of State, began preaching that the arms assigned to Canada in 1868 were composed of only the four original provinces, and he published a colour print in 1904 to make his point. His print was entitled, “Arms of the Dominion of Canada”, although the 1868 royal warrant had assigned the arms for use as a Dominion seal (fig. 22). Pope’s intentions were to eliminate the composite shields which he called “heraldic monstrosities”. His campaign was only partially successful, but shields with only the four provinces appeared on a number of Canadian Ensigns and post cards at that time. These later shields are distinguished from those just after Confederation by their much clearer and precise heraldic style. Some of them were still topped by the crown, but without all the trappings of the earlier ones (fig. 23). Sometimes, antique dealers date souvenirs with this shield as just following Confederation because they display only four provincial arms, but they are, in fact, from around 1904. So Caveat emptor! Buyer beware!

Fig. 22 Four-province shield printed at the request of Sir Joseph Pope by Mortimer and Co., Ottawa, 1904. Property of A. & P. Vachon.

Fig. 23 Postcard by Raphael Tuck & Sons, postmarked Victoria B.C., August 3, 1908. Property of A. & P. Vachon.

The arms granted to Canada in 1921, were drawn by the famous Canadian heraldic artist Alexander Scott Carter and characterized by a pointed shield in the form of a clothes iron with green maple leaves in base and art nouveau treatment of the mane and tail of the lion and unicorn supporters (fig. 24). This design was replaced in 1923 by a much more elaborate, baroque shield prepared under the supervision of Ambrose Lee, Norroy King of Arms at the College of Arms in England (fig. 25). Then in 1957 Commander Alan B. Beddoe revised the arms to include a shield resembling that of 1921 but with red maple leaves in base. He also made changes in the type of crown and the arrangement of colours in the mantling (fig. 26). In 1994 the Chief Herald of Canada, aided by Cathy Bursey-Sabourin, Fraser Herald at the Canadian Heraldic Authority, prepared a new design which added the motto of the Order of Canada on an annulus around the shield, and where the ends of the mantling took the shape of maple leaves. The base of the shield was increased in size to accommodate larger maple leaves and make them a dominant feature of the arms (fig. 27).

Fig. 24 Arms of Canada 1921 as depicted by Alexander Scott Carter. On plate by Adams, England. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

Fig. 25 Arms of Canada 1923. On plate by Porcelain Factory Arzberg, Arzberg, Germany. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

Fig. 26 Arms of Canada as revised by Alan B. Beddoe in 1957.

Fig. 27 Arms of Canada revised in 1994 to include the motto of the Order of Canada. The three maple leaves occupy a large portion of the shield and the tips of the mantling around the helmet take the shape of maple leaves.

Beside these four official versions, there were quite a few other renderings by different artists such as the design in the 1950s of Alfred Joseph Casson of the Group of Seven recognizable by a shield rounded at the base and supporters exhibiting both art deco and art nouveau characteristics (fig. 28). The Casson version did not include a helmet and mantling, but the Royal Arms of Great-Britain are often depicted this way, even by such renowned artists as Kruger Gray and Reynolds Stone who designed such versions for Her Majesty’s Stationary Office publications.

Fig. 28 Arms of Canada as designed by A.J. Casson, ca. 1965. On plate by Viletta, Canada. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

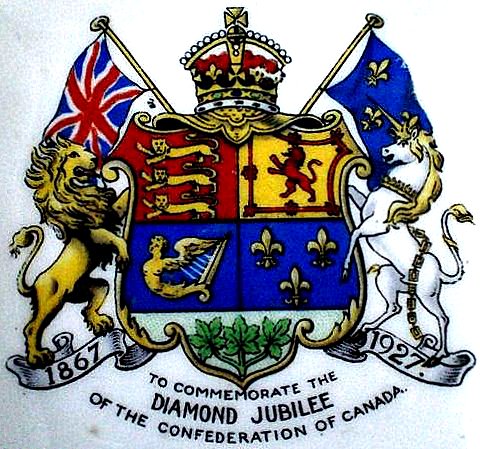

All these versions are either official or legitimate versions of Canada’s arms granted in 1921, but there were also clearly aberrant designs. One such design appearing on ceramics around 1927, removed the crest, helmet, mantling and compartment and placed the flags, held by the lion and unicorn, in saltire behind the shield (fig. 29).

Fig. 29 Aberrant version of the Arms of Canada, 1927. On pin dish by John Aynsley & Son, England. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

Using the National Arms of Canada as a didactic tool would take us back to the Middle Ages when knights used a defensive shield and a helmet covered with mantling to which was attached a crest. In the arms of Canada, the crest takes the form of a lion on its four legs holding a maple leaf. The tilting lances from which are flown the Union Flag, commonly called Union Jack, and the old banner of France remind us of the days when knights confronted one another in one-on-one combat within fenced spaces called lists. The Union Jack itself, held by a lion, prominently displays the red cross of St. George, patron saint of England, which goes back to the Crusades. Both the banner of France and the banner of St. George were flown in the early days of exploration and settlement in Canada (figs. 24-27). [12]

With the union of England and Scotland under one sovereign in 1606, the white saltire of St. Andrew, patron saint of Scotland, was added to the cross of St. George on the Union Jack. When Ireland joined the Union in 1801, the red saltire of St. Patrick came into the composition, and the flag took the form it has today. The lion and the unicorn are derived from the arms of England and Scotland respectively. The red maple leaf held by the lion in the crest can be viewed as Canada’s “red badge of courage”, since the maple leaf was included in the badge of the Canadian Expeditionary Force during the Ist World War and is now worn by members of the Royal Canadian Legion.

Looking at the central shield, one can trace the history of this country back to the United Kingdom with the gold lions of England, the rampant red lion of Scotland, the harp of Ireland, and to France by the three gold fleurs-de-lis on blue. These symbols placed together on one shield pay homage to the traditional founding nations. The same idea is repeated below the shield by a bouquet containing the rose of England, the thistle of Scotland, the shamrock of Ireland, and the lily to represent France. The sprig of three maple leaves in the tip of the shield expresses the hopes and aspirations of all Canadians and the diversity of its ethnicity. The vastness of the country from sea to sea is reflected in the motto A mari usque ad mare on a scroll beneath the shield, and since 1994, the motto of the Order of Canada appears on an annulus around the shield expressing the desire of Canadians to create a better country (Desiderentes meliorem patriam). The presence of the order’s motto also reflects a country that has come of age by establishing its own national order to recognize merit (fig. 27).

3. Heraldry as an Identification Tool

At one time or another, experts in heraldry are called upon to identify arms on such items as silverware, where they are engraved to show ownership and as a deterrent to thieves. Arms on portraits sometimes constitute the only means of identification of the sitter. The heraldist can render great services to the archaeologist who finds an unidentified armorial piece during a dig, to the museologist who grapples with a mystery artefact bearing a coat of arms, to the art historian or archivist dealing with a document or painting where arms are a key factor for identification and dating, to the art dealer whose only indication of the provenance of furniture or paintings is an armorial wax seal impressed in a discreet corner. During my career, I was called upon to identify a number of items found on sunken ships or archaeological sites. Others pieces were in museums, held by art dealers or collectors, or were family heirlooms. Several times, I was able to rescue from oblivion items of considerable historical and monetary value.

Identifying and dating artefacts by means of heraldry becomes possible because of the documentary information heraldic emblems contain. The two functions of identifying and dating are so closely interconnected that they are best treated as one process with a double purpose. Some general principles apply to any type of arms, but personal and corporate arms are looked at separately because they require a somewhat different approach.

3.1 General Approach - Before attempting to identify or date arms, one has to gain a working knowledge of heraldic language (see appendix I), be able to recognize hatchings (lines and dots indicating colours), be familiar with crowns and coronets and with various heraldic styles according to period and country, and know what tools are available to accomplish these tasks. Undertaking this type of research can prove extremely valuable as a learning experience and interesting challenge, particularly for one striving to become a heraldic scholar.

The most efficient way of identifying armorial emblems is obviously to recognize them at a glance, and this does happen sometimes with experienced heraldists. Occasionally a detective in a movie or television series will solve a mystery by recognizing arms on a button or other objects left at the crime scene, but this is not likely to happen in real life. If heraldic evidence were left at a crime scene, it would of course be given to an expert for examination, since wrong identification could have far-reaching consequences. Sometimes a depiction includes elements, particularly a motto, from which identification is possible by consulting only a few works. When quick identification does not work, even those who have delved into heraldry for many years need to follow a structured methodology.

In most cases, the first step towards successful identification is to create a file which will include a full cataloguing or descriptive sheet of the heraldic emblem and of the object on which it appears, as well as any related information. The heraldic elements may be a coat of arms or part of a coat of arms such as the crest, the crest and motto, the shield alone, or the shield with motto. It may also be a full achievement with supporters, coronets and other insignia. It may be a badge or a flag. If the heraldic device is in colour, it should be possible to arrive at a complete and accurate description. If the arms are without colours or hatching (marks that indicate colour), the description is likely to contain a lot of blanks for missing information, but this does not mean that all possibilities of success are excluded. In fact, a few elements from the shield coupled with other components such as a motto or a crest could give positive results.

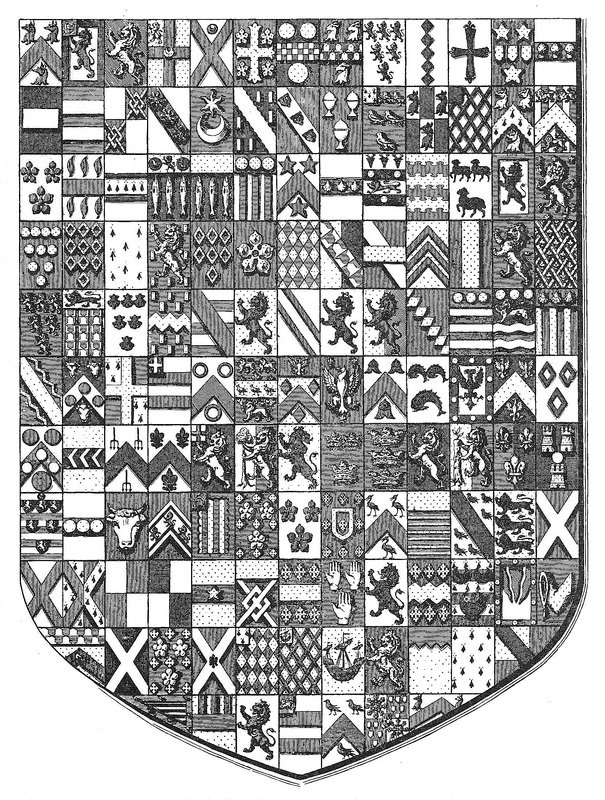

One should describe all the individual arms on a shield whether they are impaled (conjoined side by side) or quartered (four or more coats on one shield). The full description is necessary since one never knows when some of this data will open important avenues. While some descriptions are simple, others can take hours if there are numerous quarterings. If the arms contain a large number of different quarters all lined up as in figure 33, one should first describe the first two quarters and try to identify them. If this fail, chances of arriving at a positive identification are not good.

Next it is necessary to fully catalogue the item itself: what it is, what it is made of, all the makers’ marks and inscriptions. Such details as size, even colour and weight, can prove invaluable. It is also important to have a photographic record of the arms and object, particularly if the original has to be returned, or if it is too fragile or precious to carry about. Moreover, photographs can be laid out on a table for easy consultation and comparison.

The final information to add to the research file is anything relating to the previous history of the artefact, in other words its the provenance. In the case of silver for example, knowing the previous owners may greatly facilitate the identification and dating in conjunction with the engraved arms. For instance, the knowledge that something originally belonged to grandparents can help in dating and can be a useful clue to the identification of armorial insignia. Where and when it was acquired by the present owner can also prove helpful. The information on provenance may prove inaccurate upon analysis because there is a tendency to give items a prestigious origin or to make them more ancient than they really are, such as going back to the Mayflower.

Any research already performed should also be added to the file. You may be dealing with the curator of a museum or art gallery, or other experts on silver, ceramics, costume, or watermarks, who have already dated the item using another discipline. In such matters, an interdisciplinary approach is frequently the only one that will provide positive results.

3.2 Personal Arms - Some special marks of identification may appear on the shield. They may be marks of cadency that identify the order of birth of the children within a family and the different branches of a family as junior or senior. These vary from country to country and sometimes from one prominent house to another. They may be simple or complex. They may be relatively easy to recognize if they are English or Scottish, or they may require extensive research. Other marks on the shield can denote titles. A red hand on a small white shield or canton (a square in the upper left corner) denotes a baronet of England, Ireland, Great Britain or the United Kingdom. Baronets of Nova Scotia, for their part, bore, in canton or centre of the shield, a blue saltire on a white field and, in the centre of the saltire, the Royal Arms of Scotland, as do the present arms of Nova Scotia.

Other important tools for identification are coronets of rank or crowns appearing with the crest. Such coronets are all the more important that they can help establish the nationality of the arms. A crown, as opposed to a coronet, would indicate very high-ranking nobility or the arms of a country. The coronets and crowns vary from one country to another and are illustrated in various works. [13] It should be kept in mind that in some countries such as France, the coronets were often of a higher rank than the actual title of an individual and were also used by commoners. Arms may also display the insignia of orders, decorations, medals or other marks of rank or office appended below or placed behind the shield. Their identification may require research in specialized works.

Supporters (animals, persons or objects supporting the shield) also point to limited categories. Today in England supporters are symbols of eminence granted only to peers, knights of the Garter, of the Thistle and (formerly) St. Patrick, and to knights of the first class of the British orders of chivalry and of the Most Venerable Order of St John of Jerusalem. In Scotland supporters are granted, at the discretion of Lord Lyon, to peers, baronets, Knights Grand Cross of the orders of chivalry, chiefs of clans, and certain knights and the heirs of minor barons who sat in parliament prior to 1587. A person with a title of nobility should prove easier to find than a commoner because the arms are more widely recorded in published works. Municipalities and corporate bodies can also have supporters and this possibility has to be kept in mind during the identification process.

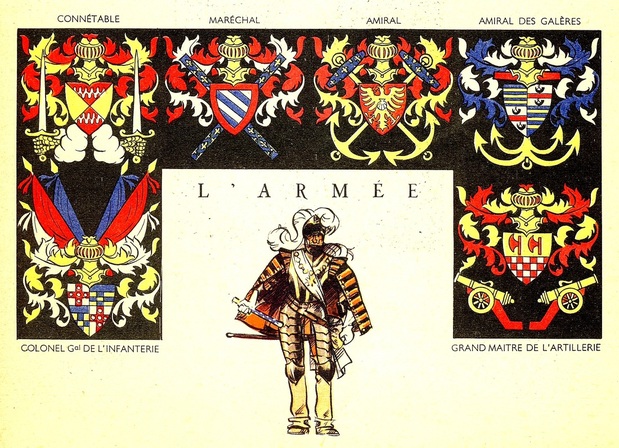

In France supporters were mostly chosen freely and could be granted to an écuyer, the lowest level of nobility. [14] The high dignitaries bore specific insignia of rank (fig. 30). The High Constable, for instance, was identified by a right hand in armour issuing from a cloud and holding a sword, on both sides outside the shield. Insignia of office placed in saltire behind the shield were frequent: two gold maces for the Chancellor, two anchors for the admiral, two gold batons strewn with blue fleurs-de-lis for the marshal, and two gold keys for the Grand Chamberlain. Napoleon’s imperial heraldry had its own marks, such as honeybees, eagles, and stars substituted for fleurs-de-lis on insignia. Caps with honeybees on the rim topped with varying numbers of ostrich feathers replaced coronets of rank. A duke of the Empire bore a red chief strewn with silver stars. Crowned batons strewn with honeybees and placed in saltire behind the shield would identify a marshal. Even colours denoted rank. Counts generally used gold figures on blue, while barons used silver on red. [15]

With the union of England and Scotland under one sovereign in 1606, the white saltire of St. Andrew, patron saint of Scotland, was added to the cross of St. George on the Union Jack. When Ireland joined the Union in 1801, the red saltire of St. Patrick came into the composition, and the flag took the form it has today. The lion and the unicorn are derived from the arms of England and Scotland respectively. The red maple leaf held by the lion in the crest can be viewed as Canada’s “red badge of courage”, since the maple leaf was included in the badge of the Canadian Expeditionary Force during the Ist World War and is now worn by members of the Royal Canadian Legion.

Looking at the central shield, one can trace the history of this country back to the United Kingdom with the gold lions of England, the rampant red lion of Scotland, the harp of Ireland, and to France by the three gold fleurs-de-lis on blue. These symbols placed together on one shield pay homage to the traditional founding nations. The same idea is repeated below the shield by a bouquet containing the rose of England, the thistle of Scotland, the shamrock of Ireland, and the lily to represent France. The sprig of three maple leaves in the tip of the shield expresses the hopes and aspirations of all Canadians and the diversity of its ethnicity. The vastness of the country from sea to sea is reflected in the motto A mari usque ad mare on a scroll beneath the shield, and since 1994, the motto of the Order of Canada appears on an annulus around the shield expressing the desire of Canadians to create a better country (Desiderentes meliorem patriam). The presence of the order’s motto also reflects a country that has come of age by establishing its own national order to recognize merit (fig. 27).

3. Heraldry as an Identification Tool

At one time or another, experts in heraldry are called upon to identify arms on such items as silverware, where they are engraved to show ownership and as a deterrent to thieves. Arms on portraits sometimes constitute the only means of identification of the sitter. The heraldist can render great services to the archaeologist who finds an unidentified armorial piece during a dig, to the museologist who grapples with a mystery artefact bearing a coat of arms, to the art historian or archivist dealing with a document or painting where arms are a key factor for identification and dating, to the art dealer whose only indication of the provenance of furniture or paintings is an armorial wax seal impressed in a discreet corner. During my career, I was called upon to identify a number of items found on sunken ships or archaeological sites. Others pieces were in museums, held by art dealers or collectors, or were family heirlooms. Several times, I was able to rescue from oblivion items of considerable historical and monetary value.

Identifying and dating artefacts by means of heraldry becomes possible because of the documentary information heraldic emblems contain. The two functions of identifying and dating are so closely interconnected that they are best treated as one process with a double purpose. Some general principles apply to any type of arms, but personal and corporate arms are looked at separately because they require a somewhat different approach.

3.1 General Approach - Before attempting to identify or date arms, one has to gain a working knowledge of heraldic language (see appendix I), be able to recognize hatchings (lines and dots indicating colours), be familiar with crowns and coronets and with various heraldic styles according to period and country, and know what tools are available to accomplish these tasks. Undertaking this type of research can prove extremely valuable as a learning experience and interesting challenge, particularly for one striving to become a heraldic scholar.

The most efficient way of identifying armorial emblems is obviously to recognize them at a glance, and this does happen sometimes with experienced heraldists. Occasionally a detective in a movie or television series will solve a mystery by recognizing arms on a button or other objects left at the crime scene, but this is not likely to happen in real life. If heraldic evidence were left at a crime scene, it would of course be given to an expert for examination, since wrong identification could have far-reaching consequences. Sometimes a depiction includes elements, particularly a motto, from which identification is possible by consulting only a few works. When quick identification does not work, even those who have delved into heraldry for many years need to follow a structured methodology.

In most cases, the first step towards successful identification is to create a file which will include a full cataloguing or descriptive sheet of the heraldic emblem and of the object on which it appears, as well as any related information. The heraldic elements may be a coat of arms or part of a coat of arms such as the crest, the crest and motto, the shield alone, or the shield with motto. It may also be a full achievement with supporters, coronets and other insignia. It may be a badge or a flag. If the heraldic device is in colour, it should be possible to arrive at a complete and accurate description. If the arms are without colours or hatching (marks that indicate colour), the description is likely to contain a lot of blanks for missing information, but this does not mean that all possibilities of success are excluded. In fact, a few elements from the shield coupled with other components such as a motto or a crest could give positive results.

One should describe all the individual arms on a shield whether they are impaled (conjoined side by side) or quartered (four or more coats on one shield). The full description is necessary since one never knows when some of this data will open important avenues. While some descriptions are simple, others can take hours if there are numerous quarterings. If the arms contain a large number of different quarters all lined up as in figure 33, one should first describe the first two quarters and try to identify them. If this fail, chances of arriving at a positive identification are not good.

Next it is necessary to fully catalogue the item itself: what it is, what it is made of, all the makers’ marks and inscriptions. Such details as size, even colour and weight, can prove invaluable. It is also important to have a photographic record of the arms and object, particularly if the original has to be returned, or if it is too fragile or precious to carry about. Moreover, photographs can be laid out on a table for easy consultation and comparison.

The final information to add to the research file is anything relating to the previous history of the artefact, in other words its the provenance. In the case of silver for example, knowing the previous owners may greatly facilitate the identification and dating in conjunction with the engraved arms. For instance, the knowledge that something originally belonged to grandparents can help in dating and can be a useful clue to the identification of armorial insignia. Where and when it was acquired by the present owner can also prove helpful. The information on provenance may prove inaccurate upon analysis because there is a tendency to give items a prestigious origin or to make them more ancient than they really are, such as going back to the Mayflower.

Any research already performed should also be added to the file. You may be dealing with the curator of a museum or art gallery, or other experts on silver, ceramics, costume, or watermarks, who have already dated the item using another discipline. In such matters, an interdisciplinary approach is frequently the only one that will provide positive results.

3.2 Personal Arms - Some special marks of identification may appear on the shield. They may be marks of cadency that identify the order of birth of the children within a family and the different branches of a family as junior or senior. These vary from country to country and sometimes from one prominent house to another. They may be simple or complex. They may be relatively easy to recognize if they are English or Scottish, or they may require extensive research. Other marks on the shield can denote titles. A red hand on a small white shield or canton (a square in the upper left corner) denotes a baronet of England, Ireland, Great Britain or the United Kingdom. Baronets of Nova Scotia, for their part, bore, in canton or centre of the shield, a blue saltire on a white field and, in the centre of the saltire, the Royal Arms of Scotland, as do the present arms of Nova Scotia.

Other important tools for identification are coronets of rank or crowns appearing with the crest. Such coronets are all the more important that they can help establish the nationality of the arms. A crown, as opposed to a coronet, would indicate very high-ranking nobility or the arms of a country. The coronets and crowns vary from one country to another and are illustrated in various works. [13] It should be kept in mind that in some countries such as France, the coronets were often of a higher rank than the actual title of an individual and were also used by commoners. Arms may also display the insignia of orders, decorations, medals or other marks of rank or office appended below or placed behind the shield. Their identification may require research in specialized works.

Supporters (animals, persons or objects supporting the shield) also point to limited categories. Today in England supporters are symbols of eminence granted only to peers, knights of the Garter, of the Thistle and (formerly) St. Patrick, and to knights of the first class of the British orders of chivalry and of the Most Venerable Order of St John of Jerusalem. In Scotland supporters are granted, at the discretion of Lord Lyon, to peers, baronets, Knights Grand Cross of the orders of chivalry, chiefs of clans, and certain knights and the heirs of minor barons who sat in parliament prior to 1587. A person with a title of nobility should prove easier to find than a commoner because the arms are more widely recorded in published works. Municipalities and corporate bodies can also have supporters and this possibility has to be kept in mind during the identification process.

In France supporters were mostly chosen freely and could be granted to an écuyer, the lowest level of nobility. [14] The high dignitaries bore specific insignia of rank (fig. 30). The High Constable, for instance, was identified by a right hand in armour issuing from a cloud and holding a sword, on both sides outside the shield. Insignia of office placed in saltire behind the shield were frequent: two gold maces for the Chancellor, two anchors for the admiral, two gold batons strewn with blue fleurs-de-lis for the marshal, and two gold keys for the Grand Chamberlain. Napoleon’s imperial heraldry had its own marks, such as honeybees, eagles, and stars substituted for fleurs-de-lis on insignia. Caps with honeybees on the rim topped with varying numbers of ostrich feathers replaced coronets of rank. A duke of the Empire bore a red chief strewn with silver stars. Crowned batons strewn with honeybees and placed in saltire behind the shield would identify a marshal. Even colours denoted rank. Counts generally used gold figures on blue, while barons used silver on red. [15]

Fig. 30 The insignia added to the shield of military and naval officers in France. From Pierre Joubert, Les lys et les lions, Les Presses de l’Île-de-France, 1947.

In Canada since 1988, all corporate bodies are entitled to supporters. In the case of personal arms, they are granted for life to governors general, lieutenant-governors, prime ministers, the chief justice of the Supreme Court, Companions of the Order of Canada, Commanders of the Order of Military Merit, Bailiffs Grand Cross and Dames Grand Cross of the Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem, the Herald Chancellor and the Deputy Herald Chancellor of the Canadian Heraldic Authority. Upon my retirement in 2000, I (Auguste Vachon) was granted supporters and given the title of Outaouais Herald Emeritus by the governor general. Likewise when Robert Watt, the first Chief Herald of Canada, retired in 2007, he received supporters and the title of Rideau Herald Emeritus. Such honours are not automatic, they are granted for outstanding service, to be borne only during the lifetime of the recipient.

If the nationality of the arms is not readily apparent, one should first attempt to determine this by using all the information compiled in the research file. Latin and French mottoes were widely used and do not denote a particular nationality, but if the motto is in another language such as Italian, German, Polish or Hungarian, the arms are likely to be from the respective country. Still there are no absolutes since people immigrate and may want to reflect something of their origins in arms designed or granted in their newly adopted country.

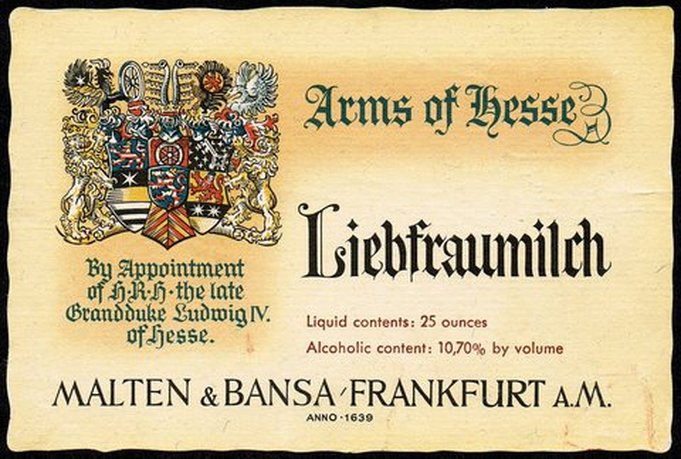

The presence of specific insignia or heraldic devices used in a particular country to denote rank should prove conclusive with respect to nationality. The experienced heraldist may be able to tell at a glance, for instance, that English, Napoleonic or German insignia are involved. Heraldic systems vary from one country to another, and to first determine the nationality of the arms will lead to the right specialized works (see appendix III and bibliography).

At other times the arms contain nothing helpful to determine nationality, but noticing this is also important, as it will orient research towards international works. Although arms granted in a certain style tend to be represented in that style for many years afterwards, the shape of the shield, the style of charges and other components such as the mantling can still provide broad clues, for instance medieval as opposed to nineteenth century. The works of Carl-Alexander von Volborth who adapted art history methodology to heraldry are particularly useful in this respect. [16] The object itself is often the best clue as to nationality, particularly if there are manufacturer’s marks. If the arms include an English motto on a piece of English silver, it is almost certainly English.

It is not always easy to know whether we are dealing with personal or corporate arms. Ecclesiastical arms are easier to recognize by the presence of specific external insignia such as hats with tassels and sometimes mitres, crosses and crosiers. But even then, there are both personal arms and those of ecclesiastical jurisdictions such as a diocese. Sometimes the shield has both: the diocesan arms on the left impaled (conjoined) with the bishop’s arms on the right.

Mural coronets that are made of masonry will normally denote a municipality, but there are exceptions to everything. The arms of Viscount Byng of Vimy include, as one of its two crests, a mural coronet representing Mouguerre in France, from which issues the colours of the 31st Regiment of Foot that he personally planted there on the enemy’s lines. In other words, his crest refers to a person, a locality in France and a British Regiment. In 1996, the Chief Herald of Canada granted Nigel Harry Richardson a crest with a mural crown in recognition of his work as an urban planner.

Quite apart from the arms, the object itself may provide dating within a decade or two and sometimes down to the month such as do some silver and ceramic marks. Dating is most important because finding to what family the arms belonged is one matter, and determining what member of that family they represent is quite another. Marks of cadency, symbols or modifications to the original arms that serve to identify senior and junior lineage, may or may not be present and are not easy to place in time. The cadency marks of a junior branch may tell us we are dealing with the fourth son of a second son, but locating these marks at a specific time within the family tree is not necessarily easy. Seeing a star on a crescent, for instance, would indicate that the arms are those of the third son of a second son, but this is not of much use without knowing to whom the arms were originally granted and where the descendants fit in. Here again heraldry goes hand in hand with genealogy.

At one point in the process, it may be a good idea to evaluate one’s chances of success. If arms, a crest and a motto are involved, chances of a positive result are normally very good. If on the other hand, the only clue is a crest in the form of a demi-lion rampant without other supporting data on file, chances are very slim. A huge number of families throughout the world have this same crest and there is no means of knowing which is represented, unless other avenues of identification exist such as provenance or other information on the artefact where the arms appear. If dealing with a demi-lion rampant holding a scimitar, chances of success are greatly increased. If the crest includes as well hatching indicating colours, chances are even better because the more the data, the more unique becomes the emblem. If the crest is accompanied by a motto on a scroll, positive identification becomes more probable because it is unlikely that two different lineages would have this same combination.

These complexities of identification may be largely eliminated as more and more information becomes available in digital form. Increasingly I would advise a search on the internet using key words of the blazon because more and more coats of arms are described on the Web. While a lot of this information is in connection with the commercial sale of arms, it may still prove useful for identification purposes.

When one has identified the arms as those of a particular family, finding the specific person they belonged to within that family constitutes another task that may prove fairly easy or very complicated. The most important element may be the artefact itself which may reveal a date from a maker’s marks which in turn would lead to members of the family living at that time. Failing this, the arms themselves may contain marks of rank that could eventually point to the right person. Supporters are excellent to identify a family, but not always helpful to identify a specific person because in the United Kingdom they often apply to a hereditary peerage that spans several generations. Conversely in many other countries, they are used freely, are not hereditary, and their use is inconsistent and not well recorded. [17] On the other hand, orders of chivalry, decorations and medals are almost inevitably lifetime honours. For this reason, they can prove essential to identify a specific person when appended below the arms.

Impaled personal arms display on one shield the arms of the husband on the left joined to those of the wife on the right (fig. 31). Should the spouse be an heiress, her shield is placed in centre of the husband’s arms as an escutcheon of pretence meaning that the children will inherit the mother’s arms. When there are several daughters and no males, each is a co-heiress, and they all transmit their father’s arms on equal terms. In such a case, all of the husbands bear the arms of their father-in-law as an escutcheon of pretence. This can prove to be an effective tool for dating if one is able to identify both the arms of the husband and wife. With the names being known, a look at a family tree should reveal when they married and provide an approximate date. In principle at least, a widower ceases to impale the arms of a deceased wife and, while a widow continues the impalement of her late husband’s arms, she does so on a lozenge. If she remarries, she will cease to use her late husband’s arms and use those of the new husband if he is armigerous (entitled to arms).

If the nationality of the arms is not readily apparent, one should first attempt to determine this by using all the information compiled in the research file. Latin and French mottoes were widely used and do not denote a particular nationality, but if the motto is in another language such as Italian, German, Polish or Hungarian, the arms are likely to be from the respective country. Still there are no absolutes since people immigrate and may want to reflect something of their origins in arms designed or granted in their newly adopted country.

The presence of specific insignia or heraldic devices used in a particular country to denote rank should prove conclusive with respect to nationality. The experienced heraldist may be able to tell at a glance, for instance, that English, Napoleonic or German insignia are involved. Heraldic systems vary from one country to another, and to first determine the nationality of the arms will lead to the right specialized works (see appendix III and bibliography).

At other times the arms contain nothing helpful to determine nationality, but noticing this is also important, as it will orient research towards international works. Although arms granted in a certain style tend to be represented in that style for many years afterwards, the shape of the shield, the style of charges and other components such as the mantling can still provide broad clues, for instance medieval as opposed to nineteenth century. The works of Carl-Alexander von Volborth who adapted art history methodology to heraldry are particularly useful in this respect. [16] The object itself is often the best clue as to nationality, particularly if there are manufacturer’s marks. If the arms include an English motto on a piece of English silver, it is almost certainly English.

It is not always easy to know whether we are dealing with personal or corporate arms. Ecclesiastical arms are easier to recognize by the presence of specific external insignia such as hats with tassels and sometimes mitres, crosses and crosiers. But even then, there are both personal arms and those of ecclesiastical jurisdictions such as a diocese. Sometimes the shield has both: the diocesan arms on the left impaled (conjoined) with the bishop’s arms on the right.

Mural coronets that are made of masonry will normally denote a municipality, but there are exceptions to everything. The arms of Viscount Byng of Vimy include, as one of its two crests, a mural coronet representing Mouguerre in France, from which issues the colours of the 31st Regiment of Foot that he personally planted there on the enemy’s lines. In other words, his crest refers to a person, a locality in France and a British Regiment. In 1996, the Chief Herald of Canada granted Nigel Harry Richardson a crest with a mural crown in recognition of his work as an urban planner.

Quite apart from the arms, the object itself may provide dating within a decade or two and sometimes down to the month such as do some silver and ceramic marks. Dating is most important because finding to what family the arms belonged is one matter, and determining what member of that family they represent is quite another. Marks of cadency, symbols or modifications to the original arms that serve to identify senior and junior lineage, may or may not be present and are not easy to place in time. The cadency marks of a junior branch may tell us we are dealing with the fourth son of a second son, but locating these marks at a specific time within the family tree is not necessarily easy. Seeing a star on a crescent, for instance, would indicate that the arms are those of the third son of a second son, but this is not of much use without knowing to whom the arms were originally granted and where the descendants fit in. Here again heraldry goes hand in hand with genealogy.

At one point in the process, it may be a good idea to evaluate one’s chances of success. If arms, a crest and a motto are involved, chances of a positive result are normally very good. If on the other hand, the only clue is a crest in the form of a demi-lion rampant without other supporting data on file, chances are very slim. A huge number of families throughout the world have this same crest and there is no means of knowing which is represented, unless other avenues of identification exist such as provenance or other information on the artefact where the arms appear. If dealing with a demi-lion rampant holding a scimitar, chances of success are greatly increased. If the crest includes as well hatching indicating colours, chances are even better because the more the data, the more unique becomes the emblem. If the crest is accompanied by a motto on a scroll, positive identification becomes more probable because it is unlikely that two different lineages would have this same combination.

These complexities of identification may be largely eliminated as more and more information becomes available in digital form. Increasingly I would advise a search on the internet using key words of the blazon because more and more coats of arms are described on the Web. While a lot of this information is in connection with the commercial sale of arms, it may still prove useful for identification purposes.

When one has identified the arms as those of a particular family, finding the specific person they belonged to within that family constitutes another task that may prove fairly easy or very complicated. The most important element may be the artefact itself which may reveal a date from a maker’s marks which in turn would lead to members of the family living at that time. Failing this, the arms themselves may contain marks of rank that could eventually point to the right person. Supporters are excellent to identify a family, but not always helpful to identify a specific person because in the United Kingdom they often apply to a hereditary peerage that spans several generations. Conversely in many other countries, they are used freely, are not hereditary, and their use is inconsistent and not well recorded. [17] On the other hand, orders of chivalry, decorations and medals are almost inevitably lifetime honours. For this reason, they can prove essential to identify a specific person when appended below the arms.

Impaled personal arms display on one shield the arms of the husband on the left joined to those of the wife on the right (fig. 31). Should the spouse be an heiress, her shield is placed in centre of the husband’s arms as an escutcheon of pretence meaning that the children will inherit the mother’s arms. When there are several daughters and no males, each is a co-heiress, and they all transmit their father’s arms on equal terms. In such a case, all of the husbands bear the arms of their father-in-law as an escutcheon of pretence. This can prove to be an effective tool for dating if one is able to identify both the arms of the husband and wife. With the names being known, a look at a family tree should reveal when they married and provide an approximate date. In principle at least, a widower ceases to impale the arms of a deceased wife and, while a widow continues the impalement of her late husband’s arms, she does so on a lozenge. If she remarries, she will cease to use her late husband’s arms and use those of the new husband if he is armigerous (entitled to arms).

Fig. 31 The arms of Arthur Alexander Greenwood impaling those of Shirley Knowles Greenwood, Nanoose Bay, British Columbia. Confirmed by the Canadian Heraldic Authority, September 15, 2005 (vol. IV, pp. 539-540). Reproduced by permission of the Canadian Heraldic Authority of Canada © Her Majesty in Right of Canada. See: http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=2383&ShowAll=1.

There are a number of other arrangements that can apply to arms of man and wife. For instance, if the husband is knight of an order and wishes to add the collar of the order around his shield, he can only add this collar to his own shield since it is personal to him. Consequently, he will place his shield with the collar on the left and his arms impaled with those of his wife on another shield to the right (fig. 32). Should a peeress in her own right marry a commoner, she cannot confer the title upon her husband. The husband’s arms will therefore include her arms as an escutcheon of pretence with the coronet or crown of her rank on top. Her own arms with her supporters will be placed on a lozenge on the right.

Fig. 32 The arms of Sir Robert Thomas White-Thomson and his wife Fanny Julia Ferguson-Davie. The shield of the husband on the left is surrounded by the ribbon with the badge of a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath to which his wife is not entitled. The husband’s arms are repeated impaled with those of his wife on the right. Fox-Davies, The Art of Heraldry, 1904, p. 198.

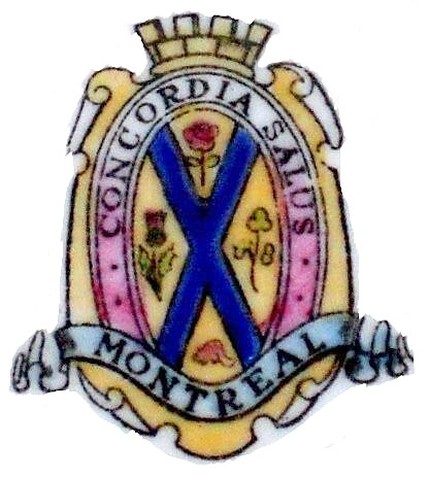

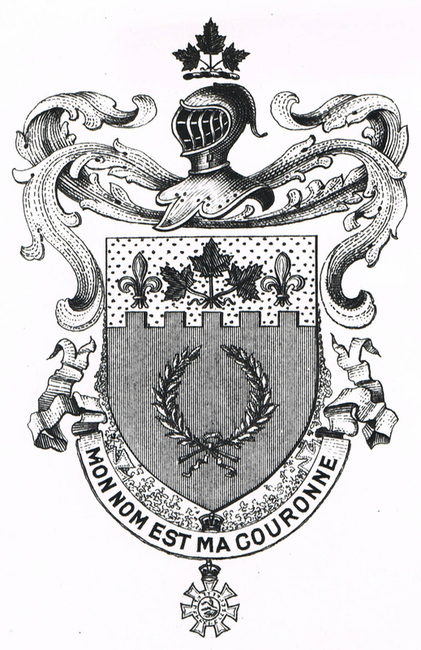

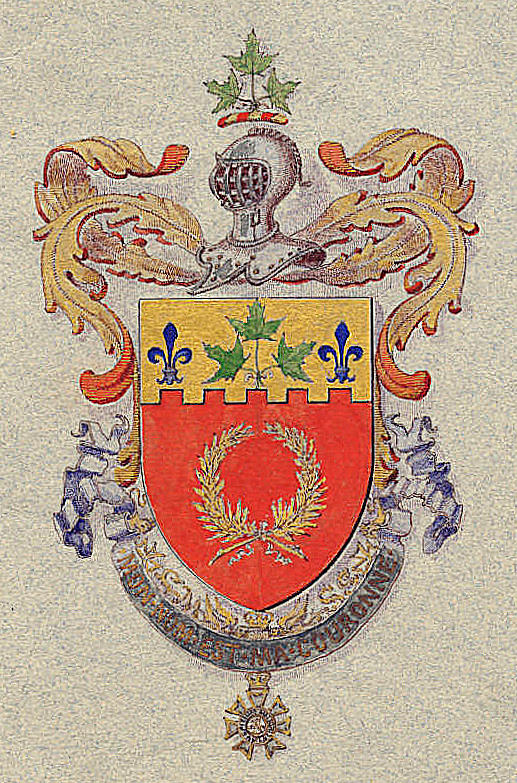

Other cases of impalement are arms of office that are placed to the left of personal arms. A mayor, for instance, is allowed to impale the arms of his municipality with his own during his tenure in office. This also applies to heads of colleges, bishops and various other offices. The task at hand is to identify the personal arms and then to discover who in that family held the office in question.