Chapter II

TAKING A CLOSER LOOK

Misunderstanding as to the nature and function of heraldry is widespread. One reason is that most people are exposed to the field through peddlers who would have the public believe that a coat of arms exists for every name and that they can provide the right one. Many Canadians ignore that coats of arms are granted to a person and descendants to be used by them alone. Another source of mistrust is the deeply rooted belief that heraldry revolves around nobility and pretence without taking into account its evolution and numerous scientific applications. It is even more distressing when these same prejudices are found among professionals such as historians, archivists and museologists who should have been exposed to heraldry as an auxiliary science to their fields. This attitude can be explained in part by the fact that auxiliary sciences to other fields such as history are not taught to any significant degree in the universities of North America. Not understanding how heraldry relates to their discipline, some professionals dismiss it as trivial or irrelevant. Of course, these misconceptions do not extend to everyone. It is in fact within these same disciplines that heraldry finds its most learned and ardent supporters.

Confusion can also arise when the adoption of public arms, such as those of a municipality, becomes a hot political issue. Local newspapers frequently dramatize the matter, though journalists rarely have any knowledge of heraldic design or of the function and significance of heraldry. Unfortunately there are few practical works that can offer guidance in these difficult situations.

Relevance Today

A common perception of heraldry is that it has become irrelevant in this modern age. This spontaneous reaction is usually based on vague general impressions that heraldry belongs to the past or to nobility; that those who seek personal arms are deluding themselves into believing that they belong to a select class. When asked why we see so many flags at Olympic Games or coat of arms on public buildings if heraldry is vain or obsolete? The answers reveal that most people have not given the matter much thought and that collective manifestations of heraldry are generally more acceptable than personal ones.

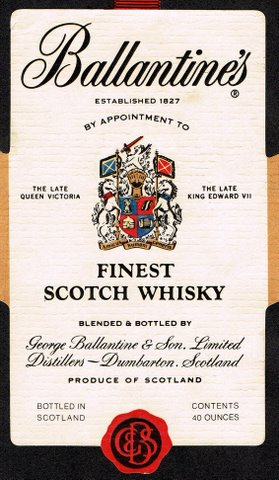

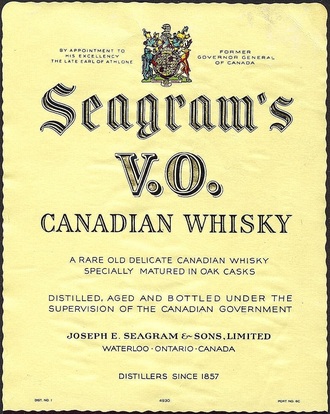

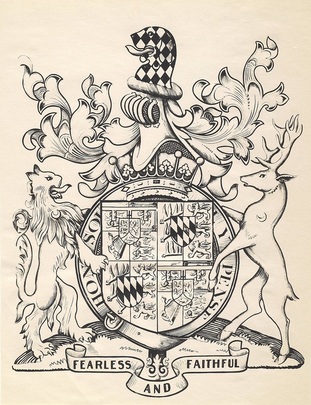

There are few houses in North America where one would not find heraldic emblems. It may be the flag of one’s country, province or state that was purchased or handed out at a special celebration. It may appear on a university diploma or an award, a government document or even a tax bill from one’s municipality. It may be on a pin, a lapel button or on a bottle in one’s liquor cabinet. Most illustrated dictionaries and encyclopaedias contain pictures of coats of arms and flags. If you own a Cadillac, you will find on it an enamelled design based on the self-attributed arms of Antoine Laumet styled de la Mothe Cadillac, the colourful and enterprising founder of Detroit.

Confusion can also arise when the adoption of public arms, such as those of a municipality, becomes a hot political issue. Local newspapers frequently dramatize the matter, though journalists rarely have any knowledge of heraldic design or of the function and significance of heraldry. Unfortunately there are few practical works that can offer guidance in these difficult situations.

Relevance Today

A common perception of heraldry is that it has become irrelevant in this modern age. This spontaneous reaction is usually based on vague general impressions that heraldry belongs to the past or to nobility; that those who seek personal arms are deluding themselves into believing that they belong to a select class. When asked why we see so many flags at Olympic Games or coat of arms on public buildings if heraldry is vain or obsolete? The answers reveal that most people have not given the matter much thought and that collective manifestations of heraldry are generally more acceptable than personal ones.

There are few houses in North America where one would not find heraldic emblems. It may be the flag of one’s country, province or state that was purchased or handed out at a special celebration. It may appear on a university diploma or an award, a government document or even a tax bill from one’s municipality. It may be on a pin, a lapel button or on a bottle in one’s liquor cabinet. Most illustrated dictionaries and encyclopaedias contain pictures of coats of arms and flags. If you own a Cadillac, you will find on it an enamelled design based on the self-attributed arms of Antoine Laumet styled de la Mothe Cadillac, the colourful and enterprising founder of Detroit.

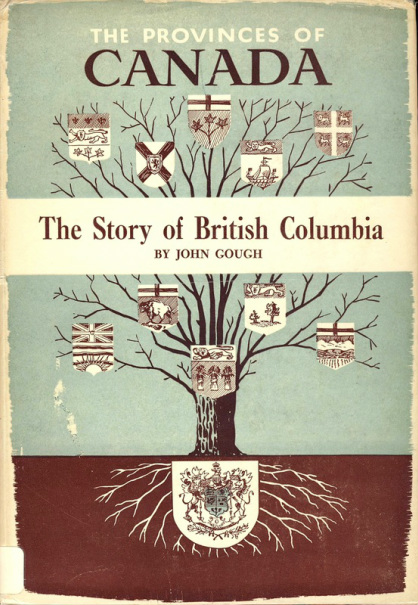

History book displaying the arms of Canada and ten provinces published as part of “The Story of Canada Series” by J. M. Dent & Sons, 1952. Similar book covers can be found in many Canadians’ library.

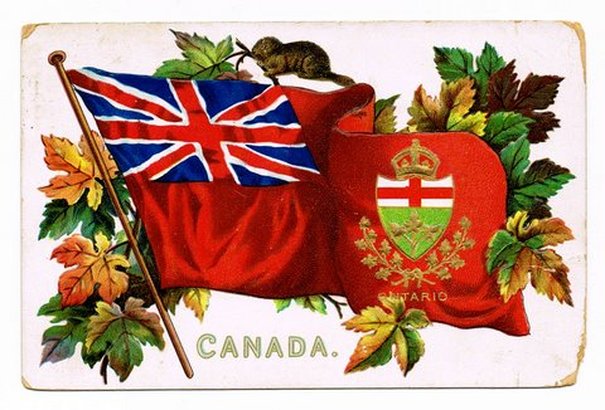

A version of the arms of Ontario on the Red Ensign by Raphael Tuck & Sons, publishers to their Majesties the King & Queen. Printed in Saxony by appointment. Postmarked London, Ontario, April 9, 1913. This card predates by 52 years the adoption of a similar flag by Ontario. Property of A. & P. Vachon.

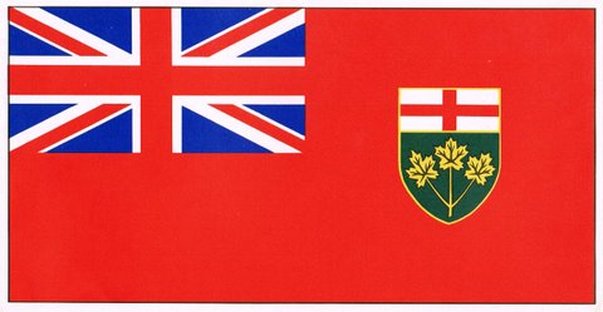

Flag of Ontario, adopted by the Legislature in 1965.

Porcelain caster with Dominion shield by Locke & Co., Worcester, England, ca. 1905. One of many utility ceramic items displaying Canadian arms created before the First World War. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

Sir Henry Percy and his horse in heraldic regalia, on a stein by Ellgreave Pottery, England. Medieval nostalgia items of this type are widely sold.

Anyone who participates in public life will encounter heraldry. It may be in the town hall or in other public places. Many hotels fly the flag of various countries, provinces or states to make guests welcome. Flags are carried into parades and are flown from ships and pleasure boats. Although some flags are not heraldic compositions, many others are in the finest heraldic tradition. Coats of arms are frequently found in stained glass windows and on historical plaques and other forms of dedications. They identify government buildings and often decorate older hotels, banks, university buildings and the stores of the Hudson’s Bay Company which still uses its arms widely. Hatchments, which represent a deceased person’s arms combined with those of a spouse or spouses, are painted on a lozenge and displayed in some churches. Bishops and dioceses usually have arms that are displayed in various places such as on cathedrae and in stained glass windows. Wherever various countries are represented, for instance at large athletic competitions, many national flags are flown. Flags serve to express patriotism after tragedies such as that of September 11th (2000) in New York. Coffins are frequently draped in the national flag, and arms are found on tombstones. The moment one makes a conscious effort to look more closely, and it is hoped that the reader will do this; one discovers that many types of heraldic manifestations are present in one’s surroundings.

Arms of the Hudson’s Bay Company, still widely used today. From Beddoe’s Canadian Heraldry, plate XXIII.

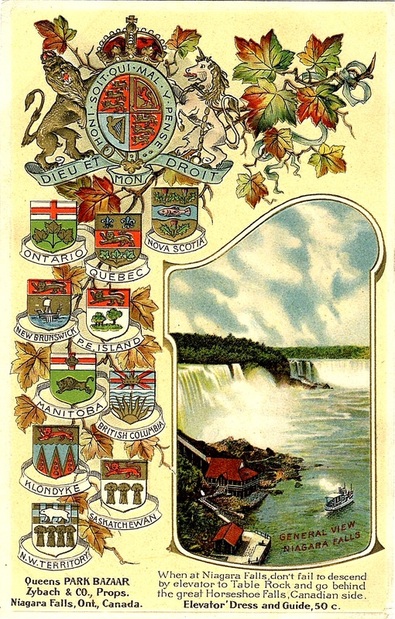

Postcard with view of Niagara Falls displaying the arms of the United Kingdom with those of Canadian provinces and territories, postdated 14 August 1907. Note the name ''Klondyke'' for the Yukon. Property of A. & P. Vachon.

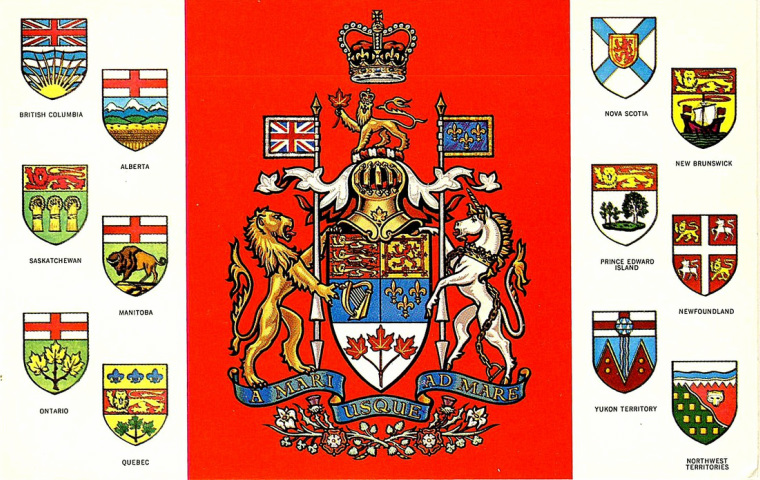

Cover of a booklet of postcards with the arms of Canada, provinces and territories, published between 1957 and 1994. Traveltime Product printed in Vancouver by Grant-Mann Lithographers. Property of A. & P. Vachon.

Throughout all of the twentieth century, Canadian patriotism was expressed by bringing coats of arms on the table in the form of numerous tea or coffee services and sometimes full dinner services. Some hotels and restaurants displayed on their ware the arms of the historical figures from whom they derive their name. Universities used their arms on cafeteria ware, ashtrays, and sometimes on finer pieces for executive or more formal use. The armed forces displayed their badges on the tableware they used in Canada and Germany. In the second half of the twentieth century, arms became fashionable on mugs and steins, particularly for universities and the Canadian Armed forces, and on all kinds of souvenirs. [1]

The idea of creating Canadian souvenirs for sale to Canadians as well as tourists made its way in the nineteenth century and became widespread in the twentieth century. Besides armorial tableware, the craze for patriotic souvenirs was remarkably strong from 1900 to 1914. [2] These souvenirs took the form of such items as Canadian Red Ensigns, postcards, silver spoons, small dishes, brooches and belt buckles. The arms of Canada began appearing on stamps in 1938 while the arms of Newfoundland were featured on a 1910 stamp commemorating the tercentenary of its foundation. [3] Today Canadian arms, national, provincial, and municipal, are seen on a variety of souvenirs. Modern methods of printing have made their reproduction on glass much easier. We find them on a variety of objects such as drinking recipients and ashtrays. They decorate T-shirts as they do in many other countries.

The idea of creating Canadian souvenirs for sale to Canadians as well as tourists made its way in the nineteenth century and became widespread in the twentieth century. Besides armorial tableware, the craze for patriotic souvenirs was remarkably strong from 1900 to 1914. [2] These souvenirs took the form of such items as Canadian Red Ensigns, postcards, silver spoons, small dishes, brooches and belt buckles. The arms of Canada began appearing on stamps in 1938 while the arms of Newfoundland were featured on a 1910 stamp commemorating the tercentenary of its foundation. [3] Today Canadian arms, national, provincial, and municipal, are seen on a variety of souvenirs. Modern methods of printing have made their reproduction on glass much easier. We find them on a variety of objects such as drinking recipients and ashtrays. They decorate T-shirts as they do in many other countries.

The 1994 Arms of Canada with two Canadian Flags on a T-Shirt.

|

Belt buckle enamelled with the Dominion shield, advertised in T. Eaton’s Catalogue 1899-1901 along with similar “patriotic pins” specifically intended for Canadians. Property of A. & P. Vachon. |

Pin dish enamelled with the shield of the Dominion, provincial emblems, and maple leaves, ca. 1900. A souvenir that was sold both to Canadians and tourists. Property of A. & P. Vachon.

|

Silver spoon souvenirs with the arms of the Dominion, c. 1900, inscribed left “Calgary,” right “Montréal.” These souvenirs spoons were popular from the start of the twentieth century. They were sold in many stores as well as catalogues, such as the T. Eaton Catalogue, along with heraldic brooches and pins. Property of A. & P. Vachon.

|

Arms of the Phi Delta Theta International Fraternity at University of Alberta. Inscribed “DEN” on opposite side, the nickname of the member. Pottery stein by Nassau China, Trenton, New Jersey, USA, 1964. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

|

Arms of Macdonald College, Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, Quebec. Pottery stein decorated by Canadian Art China, Collingwood, Ontario, 1960s. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

|

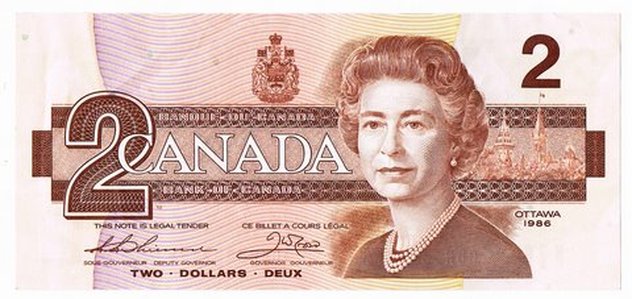

One of the fascinating aspects of Canadian emblematic history is the use of coats of arms on currency. The royal shield of France was seen on coins used in Canada at the time of New France, and the arms of both Portugal and Spain were found on coins that circulated in the colony. The royal arms of Great-Britain were also present on many coins that circulated on Canadian soil. The Hudson’s Bay Company featured its arms on notes from the 1820s, and the Bank of Montreal issued a halfpenny with the arms of Montreal in 1837. During the second half of the nineteenth century, the Royal Arms of Great Britain appeared on a number of notes as did the arms of Montreal (Bank of Montreal), and those of Nova Scotia (Bank of Nova Scotia). The Dominion arms were featured on a twenty dollar note issued by the Banque de St. Hyacinthe in 1892. It appeared on $500 to $5,000 Dominion of Canada notes from 1896 and on $5 and $10 gold coins from 1911. [4] After Canada received a grant of arms in 1921, the shield alone or the full achievement of arms began appearing on Canadian coinage and on some banknotes.

The arms of Canada on a 1986 two dollar note and on a 1979 fifty cent coin. Coats of arms appeared on coins and paper money used in Canada from early colonial times.

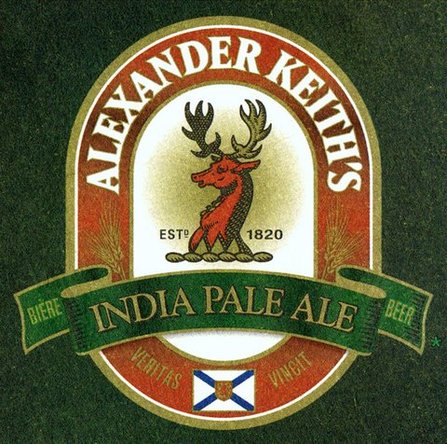

Alexander Keith’s coaster displaying the crest and motto (Veritas Vincit) of Clan Keith and the Flag of Nova Scotia.

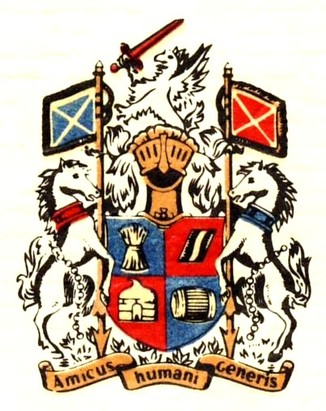

Many labels on the spirits available today feature

heraldic emblems. The Ballantine label displays the coat of arms granted to the

company by Lord Lyon, King of Arms, in 1938. The quarters of the shield

illustrate the elements required to make whisky: a sheaf of barley, pure running water, a pot still,

and a barrel to mature the product.

Many labels on the wines sold today are decked with attractive heraldic emblems as they were in the past.

That countries, provinces or states, universities, societies and churches should display coats of arms and fly flags is widely accepted. It is not that we pay much attention to them as a rule, but we feel that this is normal that they be there, and if they were to disappear suddenly, we would feel that something was missing. It is well known that whenever someone modifies public symbols, people become emotional. Personal arms, on the other hand, still bear the stigma of misconceptions. This is somewhat ironical since armorial shields originated as personal marks of identification for knights who defended the land and adhered to a code of honour.

Some have told me that, if they could discover authentic arms coming down from an ancestor through inheritance, they would display them with pride, but that they would never petition for a personal grant, as this seems too self-centred. In other words, they would be pleased if an ancestor had accomplished this presumably pretentious gesture, or again, it could possibly be left to a descendant who would feel more comfortable with the idea. Others view arms, not so much as something they want for themselves, but as something they will leave to their children as a spiritual legacy. The rationale is to leave them a memento that is not material and that will last as a special mark of family identification as long as descendants exist. In fact it is as the emblems of families that heraldry fulfils one of its most important social roles.

Nature has given all of us individual characters, traits and distinctive fingerprints. Everyone feels a natural desire to escape complete anonymity, to pull free from the grips of eternal oblivion. It is an almost universal fact that nobody wants to be a nobody. Even those engaged in philanthropic activities hope that their work will be acknowledged in some way, and not just in the afterlife. People need something unique that identifies them and their descendants and serves as an oasis in a cold world where increasingly we are all evaluated according to our possessions, credit rating, and efficiency.

Heraldry gives a sense of identity, of belonging to a greater reality, and there is no need to be deprived of its benefits because of a false sense of modesty. Genealogists undertake painstaking research to find information concerning their ancestors. They are inevitably pleased if they discover that someone has taken steps to obtain a well-documented emblem revealing something about the life and beliefs of one or several ancestors. In a country like Canada, such a step can be taken by those living presently. Arms are not only a means of surviving in the memory of posterity; they provide a sense of lineal continuity in a tangible way.

Coats of arms are powerful motivation tools, and that is why countries, cities and corporate bodies such as universities display them. They can also be a source of encouragement for members of a family over many generations. Armorial emblems beckon one to live up to certain standards in the same sense that knights lived up to certain ideals. Even a simple motto like “Never quit!” could provide oneself or a descendant with the courage and determination needed to overcome painful and difficult situations such as life inevitably presents. One account describes how Russian soldiers fighting during the Second World War drew courage from drawings of the arms of their municipality they carried in their uniform pocket: “in the dark days of retreat, these drawings served to remind us of our native town and Fatherland.” [5]

When becoming the recipient of a coat of arms, one becomes a link between the past and the future. The symbols that one adopts should not be chosen lightly. They are meant to represent what has been most significant in one’s ancestry and what we are in our innermost self, even beyond the wealth or honours we may have acquired and beyond our own shortcomings and failures. They are meant to give a message of hope and encouragement to future generations, to those who will perpetuate the lineage.

Some have told me that, if they could discover authentic arms coming down from an ancestor through inheritance, they would display them with pride, but that they would never petition for a personal grant, as this seems too self-centred. In other words, they would be pleased if an ancestor had accomplished this presumably pretentious gesture, or again, it could possibly be left to a descendant who would feel more comfortable with the idea. Others view arms, not so much as something they want for themselves, but as something they will leave to their children as a spiritual legacy. The rationale is to leave them a memento that is not material and that will last as a special mark of family identification as long as descendants exist. In fact it is as the emblems of families that heraldry fulfils one of its most important social roles.

Nature has given all of us individual characters, traits and distinctive fingerprints. Everyone feels a natural desire to escape complete anonymity, to pull free from the grips of eternal oblivion. It is an almost universal fact that nobody wants to be a nobody. Even those engaged in philanthropic activities hope that their work will be acknowledged in some way, and not just in the afterlife. People need something unique that identifies them and their descendants and serves as an oasis in a cold world where increasingly we are all evaluated according to our possessions, credit rating, and efficiency.

Heraldry gives a sense of identity, of belonging to a greater reality, and there is no need to be deprived of its benefits because of a false sense of modesty. Genealogists undertake painstaking research to find information concerning their ancestors. They are inevitably pleased if they discover that someone has taken steps to obtain a well-documented emblem revealing something about the life and beliefs of one or several ancestors. In a country like Canada, such a step can be taken by those living presently. Arms are not only a means of surviving in the memory of posterity; they provide a sense of lineal continuity in a tangible way.

Coats of arms are powerful motivation tools, and that is why countries, cities and corporate bodies such as universities display them. They can also be a source of encouragement for members of a family over many generations. Armorial emblems beckon one to live up to certain standards in the same sense that knights lived up to certain ideals. Even a simple motto like “Never quit!” could provide oneself or a descendant with the courage and determination needed to overcome painful and difficult situations such as life inevitably presents. One account describes how Russian soldiers fighting during the Second World War drew courage from drawings of the arms of their municipality they carried in their uniform pocket: “in the dark days of retreat, these drawings served to remind us of our native town and Fatherland.” [5]

When becoming the recipient of a coat of arms, one becomes a link between the past and the future. The symbols that one adopts should not be chosen lightly. They are meant to represent what has been most significant in one’s ancestry and what we are in our innermost self, even beyond the wealth or honours we may have acquired and beyond our own shortcomings and failures. They are meant to give a message of hope and encouragement to future generations, to those who will perpetuate the lineage.

The Past Lives On

Heraldry is frequently discarded as being something of the past, something we don’t need today. Yet the reader of this book may be sitting in a chair, perhaps at a table with a cup and saucer, in a house, on a street all of which came into being centuries ago. The public in general has a vague awareness that knights bore heraldic shields into battle and at tournaments, and that heraldry was part of the knight’s life in former days. Their image of medieval times is often a quixotic version that is centred on chivalric and amorous exploits, as generally promoted by the film industry. In other words, medieval life tends to become a fairy tale and is frequently assimilated to the fiction of the period such as the legend of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. Of course this can make heraldry popular which is important, but it does not do much to promote its image as a serious science and a demanding art.

Like so many other realities, heraldry is something that has survived from former times because it remains useful. As we see throughout this work, it is an art and a science and neither art nor science is easily destroyed. No one has ever succeeded in destroying very ancient arts such as painting, sculpture, music and poetry. Heraldry also embodies abstract notions and ideas in the form of symbolism and symbols are “monuments more lasting than bronze” to quote the Roman poet Horace.

One reason for such misconceptions is that many historians have been taught to use printed and manuscript sources, but rarely visual documents. In fact for some historians, textual documents are the only ones that are worthy of consideration. A painting, drawing or print, a medal, a seal or a coat of arms are rarely seen as having historical value. All too often the few experts in such fields as numismatics, sigillography (study of seals) or heraldry are viewed as having strayed off the beaten path, something I know from experience. In European archives, these areas are generally well-respected specialties. Fortunately there are signs that they are slowly gaining grounds in America, particularly as the teaching of historical methodology and archival sciences become more widespread and better structured.

Changes in public heraldic emblems or the adoption of new ones frequently attract the attention of journalists. Some journalists take time to find out what they are dealing with and report in correct sober terms. Others clearly use heraldry to promote political views and arouse indignation. Such articles usually take a declamatory tone with only the skimpiest grasp of what is involved. When the motto of the Order of Canada “Desiderantes meliorem patriam” (They desire a better country) was added around the shield of Canada’s arms in 1994, this was done in imitation of the arms of Great Britain that are surrounded by the motto of the Order of the Garter “Honi soit qui mal y pense”. This change gave rise to many indignant and ill-founded reactions in the press. [6]

Strome Galloway, the author of Beddoe’s Canadian Heraldry and editor emeritus of Heraldry in Canada once remarked: “It is strange how people accept that engineers or doctors must study for many years to be qualified, while people think they can become experts in heraldry overnight.” In a more positive vein, objections to the 1994 changes in the arms of Canada did show that Canadians cared for their national symbols. Of course the sort of passionate and rather imaginative reporting mentioned here is by no means exclusive to Canada. It takes place in other countries with freedom of the press whenever emblems undergo a change. In the summer of 1970, Gérard Pelletier, Secretary of State, declared in a television interview that traditional symbols like the Canadian coat of arms “do not mean a thing in the 20th century”. He went on to state that “We could put Schenley’s (a whiskey brand) coat of arms on government buildings and no one would know the difference.” [7] Ironically some twenty-five years later, his successor, Heritage Minister Michel Dupuy, was struggling to ward off criticism as the public learned that Canada’s arms had been revised. [8]

Heraldry is deemed by some to be snobbish because it is viewed as belonging to a special class. In fact all people who associate with the arts such as theatre, opera, ballet, music and painting (all things that came into existence centuries ago) are sometimes branded as snobs, though this word should be used with caution. In fact, most people who support the arts do so out of genuine appreciation. They come from all walks of life and remain loyal to their art forms over a lifetime. It would seem that appreciation of the arts is something that certain persons have and others don’t, no matter what their level of education or wealth may be.

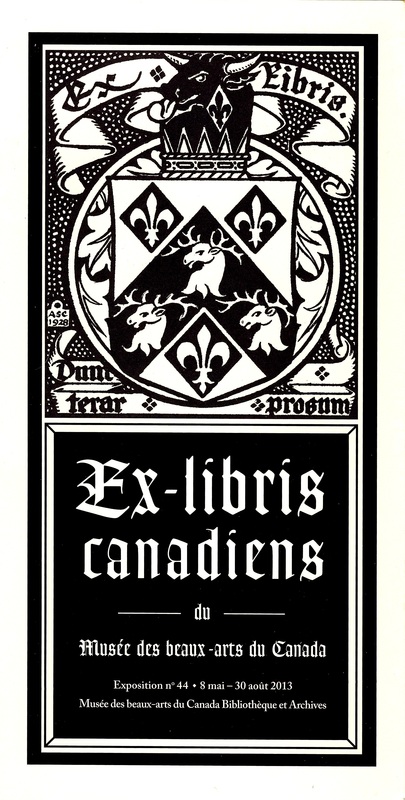

Most heraldry enthusiasts are attached to tradition and family values and love the colour and pageantry that heraldry provides. Some are avid readers in the field and quite knowledgeable while others are more interested in researching and writing or specializing in a particular aspect such as its nature and applications as defined by the laws of a particular country. Others still are collectors of heraldic bookplates, stamps, medals, ceramics, and so on. Heraldry societies are open to all and have reasonable membership fees that usually include a publication.

Heraldry is frequently discarded as being something of the past, something we don’t need today. Yet the reader of this book may be sitting in a chair, perhaps at a table with a cup and saucer, in a house, on a street all of which came into being centuries ago. The public in general has a vague awareness that knights bore heraldic shields into battle and at tournaments, and that heraldry was part of the knight’s life in former days. Their image of medieval times is often a quixotic version that is centred on chivalric and amorous exploits, as generally promoted by the film industry. In other words, medieval life tends to become a fairy tale and is frequently assimilated to the fiction of the period such as the legend of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. Of course this can make heraldry popular which is important, but it does not do much to promote its image as a serious science and a demanding art.

Like so many other realities, heraldry is something that has survived from former times because it remains useful. As we see throughout this work, it is an art and a science and neither art nor science is easily destroyed. No one has ever succeeded in destroying very ancient arts such as painting, sculpture, music and poetry. Heraldry also embodies abstract notions and ideas in the form of symbolism and symbols are “monuments more lasting than bronze” to quote the Roman poet Horace.

One reason for such misconceptions is that many historians have been taught to use printed and manuscript sources, but rarely visual documents. In fact for some historians, textual documents are the only ones that are worthy of consideration. A painting, drawing or print, a medal, a seal or a coat of arms are rarely seen as having historical value. All too often the few experts in such fields as numismatics, sigillography (study of seals) or heraldry are viewed as having strayed off the beaten path, something I know from experience. In European archives, these areas are generally well-respected specialties. Fortunately there are signs that they are slowly gaining grounds in America, particularly as the teaching of historical methodology and archival sciences become more widespread and better structured.

Changes in public heraldic emblems or the adoption of new ones frequently attract the attention of journalists. Some journalists take time to find out what they are dealing with and report in correct sober terms. Others clearly use heraldry to promote political views and arouse indignation. Such articles usually take a declamatory tone with only the skimpiest grasp of what is involved. When the motto of the Order of Canada “Desiderantes meliorem patriam” (They desire a better country) was added around the shield of Canada’s arms in 1994, this was done in imitation of the arms of Great Britain that are surrounded by the motto of the Order of the Garter “Honi soit qui mal y pense”. This change gave rise to many indignant and ill-founded reactions in the press. [6]

Strome Galloway, the author of Beddoe’s Canadian Heraldry and editor emeritus of Heraldry in Canada once remarked: “It is strange how people accept that engineers or doctors must study for many years to be qualified, while people think they can become experts in heraldry overnight.” In a more positive vein, objections to the 1994 changes in the arms of Canada did show that Canadians cared for their national symbols. Of course the sort of passionate and rather imaginative reporting mentioned here is by no means exclusive to Canada. It takes place in other countries with freedom of the press whenever emblems undergo a change. In the summer of 1970, Gérard Pelletier, Secretary of State, declared in a television interview that traditional symbols like the Canadian coat of arms “do not mean a thing in the 20th century”. He went on to state that “We could put Schenley’s (a whiskey brand) coat of arms on government buildings and no one would know the difference.” [7] Ironically some twenty-five years later, his successor, Heritage Minister Michel Dupuy, was struggling to ward off criticism as the public learned that Canada’s arms had been revised. [8]

Heraldry is deemed by some to be snobbish because it is viewed as belonging to a special class. In fact all people who associate with the arts such as theatre, opera, ballet, music and painting (all things that came into existence centuries ago) are sometimes branded as snobs, though this word should be used with caution. In fact, most people who support the arts do so out of genuine appreciation. They come from all walks of life and remain loyal to their art forms over a lifetime. It would seem that appreciation of the arts is something that certain persons have and others don’t, no matter what their level of education or wealth may be.

Most heraldry enthusiasts are attached to tradition and family values and love the colour and pageantry that heraldry provides. Some are avid readers in the field and quite knowledgeable while others are more interested in researching and writing or specializing in a particular aspect such as its nature and applications as defined by the laws of a particular country. Others still are collectors of heraldic bookplates, stamps, medals, ceramics, and so on. Heraldry societies are open to all and have reasonable membership fees that usually include a publication.

Cover of the catalogue of an exhibition of Canadian bookplates at the National Gallery of Canada in 2013. The bookplate is that of the Right Honourable Vincent Massey created by Alexander Scott Carter. Many other heraldic bookplates were on display. There are many collectors of heraldic bookplates that are still created today.

Most grants of arms today are not made to nobility, but to non-nobles or “commoners” as they are sometimes called. English kings of arms began granting to “eminent men” from the fifteenth century and, of course, although titles subsist in Great Britain, commoners have the right to petition for a grant of arms. In France arms were almost exclusively granted to nobles prior to the Edict of 1696 which extended grants to the bourgeois class, but everyone, noble or commoner, had the legal right to freely adopt and bear arms long before that date.

The arms granted in Canada have nothing to do with titles of nobility. Canadians can no longer receive foreign titles and Canada has never granted titles. But a Canadian citizen can hold dual citizenship; have a title that is recognized in one country and not in the other. If a titled immigrant becomes a Canadian citizen, no one will interfere with the use of the title in correspondence and in society, but the Canadian government will not officially recognize or validate the title in any way.

In Canada a grant of arms is considered an honour from the Canadian Crown and requires some degree of merit, but it is not restrictive. Anyone who has done community, voluntary or charitable work, or has contributed in some way to the well-being of others would normally qualify. The potential grantee is recommended by a herald to the Herald Chancellor or Deputy Herald Chancellor who issues a warrant to the Chief Herald of Canada authorizing the grant. For further information, readers should consult the Canadian Heraldic Authority section of the Rideau Hall site.

The arms granted in Canada have nothing to do with titles of nobility. Canadians can no longer receive foreign titles and Canada has never granted titles. But a Canadian citizen can hold dual citizenship; have a title that is recognized in one country and not in the other. If a titled immigrant becomes a Canadian citizen, no one will interfere with the use of the title in correspondence and in society, but the Canadian government will not officially recognize or validate the title in any way.

In Canada a grant of arms is considered an honour from the Canadian Crown and requires some degree of merit, but it is not restrictive. Anyone who has done community, voluntary or charitable work, or has contributed in some way to the well-being of others would normally qualify. The potential grantee is recommended by a herald to the Herald Chancellor or Deputy Herald Chancellor who issues a warrant to the Chief Herald of Canada authorizing the grant. For further information, readers should consult the Canadian Heraldic Authority section of the Rideau Hall site.

The World of Bogus Heraldry

Bogus heraldry involves selling someone a coat of arms based on a name only. No genealogical research is done to uncover authentic arms or alternately to demonstrate that an individual has no entitlement to ancestral arms. In extremely rare cases, these peddlers will, by pure chance, find arms that actually belong to a client’s ancestry, but they supply no genealogical proof of this. As a rule, they will sell a person arms that belong to another family with the same name. Usually the arms are accompanied by diffuse generalities concerning ancestry that are of no practical use. Their certificates may contain information on the origins of the name that can be found in a number of name dictionaries. They frequently mention illustrious persons with the same name found in encyclopaedias, but who are rarely related to one’s own lineage. Statements to the effect that one’s family is very ancient (we all go back to Adam and Eve) and fought bravely in many wars may be true, but can be made of almost any family. In England and many other European countries, arms are granted to one person and descendants and, unless one can prove descent from the person to whom the arms were granted, one cannot claim a historical right to arms.

A contrivance of certain peddlers is to make the recipient believe that some arms are so ancient that they belong to all persons of a given name. As we know, in Scotland all arms are registered under a specific name in the Lord Lyon’s Register with individual differences for each. From the fifteenth century, there have been in England, a number of visitations by heraldic officers aimed at eliminating the illegitimate use of arms.

Hawkers of bogus arms can have many tricks up their sleeve. If they do not find your name in an armorial (book illustrating and/or describing arms), some will not hesitate to sell clients those of a person with a similar name though the owner of the arms may be of a completely different nationality. The armorials they refer to are almost always The General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales by Sir Bernard Burke often called Burke’s General Armory and J.B. Rietstap’s Armorial Général. During my days at the National Archives of Canada (now Library and Archives Canada), I sometimes ran across cases of modern attributions for families that had been extinct for centuries. An article in the Family Chronicle mentions a modern attribution of arms for the name Moorshead, although the line of the original recipient, William Morshead (note the spelling), had become extinct in the early 1900s. [9] Another popular trick is to create arms for a person whose name does not appear in the above works. This usually involves taking elements from one existing shield and combining them with elements from another. Such arms are meaningless for the recipient, but the purveyor of such insignificant tokens has made money and is happy.

Often boutiques will get away with selling arms that supposedly belong to one’s clan. Books on Scottish clans can contain arms as do maps, but these are the arms of the chief of the clan and can only be used by the rightful chief when duly registered in his name in the Public Register of all Arms and Bearings in Scotland. Scottish heraldic law is strict but clear. Every generation must have its arms matriculated, that is, duly registered and individually differenced. In other words, if a person does not have arms matriculated in his name, that person has no arms at all as far as Scottish authorities are concerned. If one decides to design and freely adopt personal arms, they do not exist as arms in Scottish heraldic law. On the other hand, all clan members are allowed to wear the clan bonnet badge that consists of the crest from the chief’s arms within a strap-and-buckle bearing the chief’s motto. A clan member may also petition for the grant of a coat of arms patterned after that of the chief and clearly identifying the bearer of the arms as belonging to a particular clan, but sufficiently differenced to make them unique to the grantee. [10]

Today some individuals or firms in France will produce coats of arms for North Americans of French descent or for family associations with a French name that have members all over the continent. Their claim to legally register such arms is misleading. In France, a copy of anything that is printed has to be deposited by law with the Department of the Interior (Ministère de l’intérieur) and any printed image has to be deposited at the National Library (Bibliothèque nationale). This legal deposit aims at conserving the printed heritage of France and offers in itself no protection of intellectual property. It is not unlike the Canadian Legal Deposit for published material. Banking on this requirement of compulsory deposit, a number of French heraldists have tried to convince recipients that the process makes the arms official. This is all the more ironic that France presently has no mechanism to grant or make the arms of its own citizens and corporate bodies official. One “heraldist” further informs clients that their arms are registered in the Armorial of France and Europe, which is a kind of compilation with no official status. There is nothing wrong with compiling arms, but if they have no official status to begin with, including them in some kind of register or armorial will not make them more official. The Republic of France has a Commission nationale d’héraldique presided over by the Director of the National Archives of France that acts in an advisory capacity for the creation of new territorial arms or the modification of such arms. [11]

The only persons who can officially grant arms in Canada since 1988 are the Governor General and the Chief Herald of Canada, both acting on behalf of the Canadian Crown. No person or institution from another country can give Canadian arms an official status. Arms officially granted by the Canadian Heraldic Authority can be protected under Section 9(1) (n.1) of the Trade-Marks Act. If one should wish to remain in the domain of assumed arms as opposed to officially granted ones, one could protect a newly created coat of arms by registering it as an original artistic creation under our own Canadian Copyright Act. But again it should be remembered that this registration for intellectual protection is not the same as the grant of an honour from the Crown.

The question inevitably arises as to why bogus heraldry is not prevented by law. Of course legal action is sometimes taken if there are enough complaints from the public, but even then it is not always effective. My own experience in this area will provide some insight. In 1985, I was subpoenaed to appear in the Provincial Court of Ontario within the Judicial District of Ottawa-Carleton as an expert witness in a case where a company named Halbert’s was accused under the Combines Investigation Act of providing false and misleading advertisement, part of which related to genealogy and heraldry. The company was convicted of three counts of false and misleading advertisement and fined $9,000. This conviction was reported in a number of Canadian newspapers, but it did not stop the company’s activities. [12]

In 1991 I received a letter from Consumer and Corporate Affairs informing me that I was required to appear as a witness for the Crown in the City Hall Court House in Toronto in a case involving the same company and similar infractions of false and misleading advertisement. When the subpoena did not arrive, I called Consumer and Corporate Affairs to be informed that the company had paid a fine and would not appear in court. And they simply continued to sell their dubious arms and genealogical generalities by mail. Some time later, I received a letter from Halbert’s, operating from Pierrefonds (Quebec) and offering to sell me a wonderful book regarding the Vachons. The book, which I bought as evidence should I be summoned to court again, in fact included the arms of a noble Vachon family of a different lineage whose only representative in Canada had been the Sulpician priest François Vachon de Belmont (1645-1732), an historian like myself, but not my ancestor, I am sure!

The only safeguard against being sold bogus family heraldry is public education. Many genealogical societies are warning their members to stay away from heraldry hawkers, but a great deal remains to be done. Many customers are happy to pay for what they believe to be their authentic arms, all the more so that the amounts are usually not that high. But in other cases, Canadian citizens have complained to me that they had paid hundreds of dollars to certain arms peddlers only to realize later that what they had received was bogus.

There are a number of ways one can avoid being the victim of bogus heraldry.

1) Do not be in a hurry. Some people call the Canadian Heraldic Authority or Library and Archives Canada a few weeks in advance of Christmas or of an anniversary looking for a coat of arms as a gift for someone. Because these institutions cannot help them within this time frame, they are happy to use the services of hawkers who can supply something on time without any concern for authenticity.

2) Do not buy arms offered by mail or being sold by a firm having set up shop in airports, shopping centres, hotels or other public places.

3 Never buy arms from someone who readily finds them on a computer. Right to ancestral arms is based on genealogy. If an arms company does not know who your father or grandfather was, there is no way that it can establish your entitlement to ancestral arms. The perspective buyer should ask to which ancestor the arms were granted, and to be shown how the arms being offered have come to him or her by descent.

4) Refuse to be taken in by some advertisements on the web where peddlers assume the most official sounding titles and claim their right to sell arms from the highest imperial or royal authority.

5) The correct way to proceed is outlined in chapter IV. One should not hesitate to consult the site of the Canadian Heraldic Authority or to ask one of its heralds for further clarification.

There are instances where someone has obtained an armorial plaque from a hawker to grace the walls of a den, though well aware that the arms were not authentic. This is a very easy-going approach to the matter. Taking time to reflect that, in all likelihood, someone else’s coat arms is being displayed on the wall, might stir a few pangs of guilt. But often the real victims are the children of the purchaser who will inevitably grow up thinking that the family possesses authentic arms and will likely be disappointed if they find out that their parents have been flaunting arms belonging to another lineage.

As in other countries, bogus heraldry in Canada is not likely to be completely eradicated. All one can do is keep on preaching that a claim to ancestral arms is based on descent from someone to whom arms were granted by the official heraldic authorities of a sovereign country and that one must prove descent, usually in the male line, from the specific ancestor to whom the arms were granted or, for some countries of Eastern Europe, a specific family group usually called a clan! But even in a case where research leads to ancestral arms, the claim will remain a historical one unless the country where the arms originated recognizes the claim, or the country where the claimant may now be living is able to confirm the entitlement based on solid documentation and possibly make the confirmation official.

Prior to the establishment of the Canadian Heraldic Authority in 1988, officers of the Crown in England or Scotland made grants to Canadian citizens, municipalities and a few other corporate bodies. [13] There is no doubt that these grants are legal and valid in Canada even after 1988. But many other Canadians bear arms from Europe for which the entitlement is no longer clear for various reasons such as: a change from a monarchy to a republic in the country of origin, the loss of documentation, or variances introduced over the years in the depiction of the arms. In Canada, it would be important to have these arms confirmed by the Canadian Heraldic Authority, even if a new Canadian grant with differences might be required. In fact, even when the entitlement can be easily proven, it seems important to register the arms in Canada so that descendants will have a clear record in the country where they live.

Bogus heraldry involves selling someone a coat of arms based on a name only. No genealogical research is done to uncover authentic arms or alternately to demonstrate that an individual has no entitlement to ancestral arms. In extremely rare cases, these peddlers will, by pure chance, find arms that actually belong to a client’s ancestry, but they supply no genealogical proof of this. As a rule, they will sell a person arms that belong to another family with the same name. Usually the arms are accompanied by diffuse generalities concerning ancestry that are of no practical use. Their certificates may contain information on the origins of the name that can be found in a number of name dictionaries. They frequently mention illustrious persons with the same name found in encyclopaedias, but who are rarely related to one’s own lineage. Statements to the effect that one’s family is very ancient (we all go back to Adam and Eve) and fought bravely in many wars may be true, but can be made of almost any family. In England and many other European countries, arms are granted to one person and descendants and, unless one can prove descent from the person to whom the arms were granted, one cannot claim a historical right to arms.

A contrivance of certain peddlers is to make the recipient believe that some arms are so ancient that they belong to all persons of a given name. As we know, in Scotland all arms are registered under a specific name in the Lord Lyon’s Register with individual differences for each. From the fifteenth century, there have been in England, a number of visitations by heraldic officers aimed at eliminating the illegitimate use of arms.

Hawkers of bogus arms can have many tricks up their sleeve. If they do not find your name in an armorial (book illustrating and/or describing arms), some will not hesitate to sell clients those of a person with a similar name though the owner of the arms may be of a completely different nationality. The armorials they refer to are almost always The General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales by Sir Bernard Burke often called Burke’s General Armory and J.B. Rietstap’s Armorial Général. During my days at the National Archives of Canada (now Library and Archives Canada), I sometimes ran across cases of modern attributions for families that had been extinct for centuries. An article in the Family Chronicle mentions a modern attribution of arms for the name Moorshead, although the line of the original recipient, William Morshead (note the spelling), had become extinct in the early 1900s. [9] Another popular trick is to create arms for a person whose name does not appear in the above works. This usually involves taking elements from one existing shield and combining them with elements from another. Such arms are meaningless for the recipient, but the purveyor of such insignificant tokens has made money and is happy.

Often boutiques will get away with selling arms that supposedly belong to one’s clan. Books on Scottish clans can contain arms as do maps, but these are the arms of the chief of the clan and can only be used by the rightful chief when duly registered in his name in the Public Register of all Arms and Bearings in Scotland. Scottish heraldic law is strict but clear. Every generation must have its arms matriculated, that is, duly registered and individually differenced. In other words, if a person does not have arms matriculated in his name, that person has no arms at all as far as Scottish authorities are concerned. If one decides to design and freely adopt personal arms, they do not exist as arms in Scottish heraldic law. On the other hand, all clan members are allowed to wear the clan bonnet badge that consists of the crest from the chief’s arms within a strap-and-buckle bearing the chief’s motto. A clan member may also petition for the grant of a coat of arms patterned after that of the chief and clearly identifying the bearer of the arms as belonging to a particular clan, but sufficiently differenced to make them unique to the grantee. [10]

Today some individuals or firms in France will produce coats of arms for North Americans of French descent or for family associations with a French name that have members all over the continent. Their claim to legally register such arms is misleading. In France, a copy of anything that is printed has to be deposited by law with the Department of the Interior (Ministère de l’intérieur) and any printed image has to be deposited at the National Library (Bibliothèque nationale). This legal deposit aims at conserving the printed heritage of France and offers in itself no protection of intellectual property. It is not unlike the Canadian Legal Deposit for published material. Banking on this requirement of compulsory deposit, a number of French heraldists have tried to convince recipients that the process makes the arms official. This is all the more ironic that France presently has no mechanism to grant or make the arms of its own citizens and corporate bodies official. One “heraldist” further informs clients that their arms are registered in the Armorial of France and Europe, which is a kind of compilation with no official status. There is nothing wrong with compiling arms, but if they have no official status to begin with, including them in some kind of register or armorial will not make them more official. The Republic of France has a Commission nationale d’héraldique presided over by the Director of the National Archives of France that acts in an advisory capacity for the creation of new territorial arms or the modification of such arms. [11]

The only persons who can officially grant arms in Canada since 1988 are the Governor General and the Chief Herald of Canada, both acting on behalf of the Canadian Crown. No person or institution from another country can give Canadian arms an official status. Arms officially granted by the Canadian Heraldic Authority can be protected under Section 9(1) (n.1) of the Trade-Marks Act. If one should wish to remain in the domain of assumed arms as opposed to officially granted ones, one could protect a newly created coat of arms by registering it as an original artistic creation under our own Canadian Copyright Act. But again it should be remembered that this registration for intellectual protection is not the same as the grant of an honour from the Crown.

The question inevitably arises as to why bogus heraldry is not prevented by law. Of course legal action is sometimes taken if there are enough complaints from the public, but even then it is not always effective. My own experience in this area will provide some insight. In 1985, I was subpoenaed to appear in the Provincial Court of Ontario within the Judicial District of Ottawa-Carleton as an expert witness in a case where a company named Halbert’s was accused under the Combines Investigation Act of providing false and misleading advertisement, part of which related to genealogy and heraldry. The company was convicted of three counts of false and misleading advertisement and fined $9,000. This conviction was reported in a number of Canadian newspapers, but it did not stop the company’s activities. [12]

In 1991 I received a letter from Consumer and Corporate Affairs informing me that I was required to appear as a witness for the Crown in the City Hall Court House in Toronto in a case involving the same company and similar infractions of false and misleading advertisement. When the subpoena did not arrive, I called Consumer and Corporate Affairs to be informed that the company had paid a fine and would not appear in court. And they simply continued to sell their dubious arms and genealogical generalities by mail. Some time later, I received a letter from Halbert’s, operating from Pierrefonds (Quebec) and offering to sell me a wonderful book regarding the Vachons. The book, which I bought as evidence should I be summoned to court again, in fact included the arms of a noble Vachon family of a different lineage whose only representative in Canada had been the Sulpician priest François Vachon de Belmont (1645-1732), an historian like myself, but not my ancestor, I am sure!

The only safeguard against being sold bogus family heraldry is public education. Many genealogical societies are warning their members to stay away from heraldry hawkers, but a great deal remains to be done. Many customers are happy to pay for what they believe to be their authentic arms, all the more so that the amounts are usually not that high. But in other cases, Canadian citizens have complained to me that they had paid hundreds of dollars to certain arms peddlers only to realize later that what they had received was bogus.

There are a number of ways one can avoid being the victim of bogus heraldry.

1) Do not be in a hurry. Some people call the Canadian Heraldic Authority or Library and Archives Canada a few weeks in advance of Christmas or of an anniversary looking for a coat of arms as a gift for someone. Because these institutions cannot help them within this time frame, they are happy to use the services of hawkers who can supply something on time without any concern for authenticity.

2) Do not buy arms offered by mail or being sold by a firm having set up shop in airports, shopping centres, hotels or other public places.

3 Never buy arms from someone who readily finds them on a computer. Right to ancestral arms is based on genealogy. If an arms company does not know who your father or grandfather was, there is no way that it can establish your entitlement to ancestral arms. The perspective buyer should ask to which ancestor the arms were granted, and to be shown how the arms being offered have come to him or her by descent.

4) Refuse to be taken in by some advertisements on the web where peddlers assume the most official sounding titles and claim their right to sell arms from the highest imperial or royal authority.

5) The correct way to proceed is outlined in chapter IV. One should not hesitate to consult the site of the Canadian Heraldic Authority or to ask one of its heralds for further clarification.

There are instances where someone has obtained an armorial plaque from a hawker to grace the walls of a den, though well aware that the arms were not authentic. This is a very easy-going approach to the matter. Taking time to reflect that, in all likelihood, someone else’s coat arms is being displayed on the wall, might stir a few pangs of guilt. But often the real victims are the children of the purchaser who will inevitably grow up thinking that the family possesses authentic arms and will likely be disappointed if they find out that their parents have been flaunting arms belonging to another lineage.

As in other countries, bogus heraldry in Canada is not likely to be completely eradicated. All one can do is keep on preaching that a claim to ancestral arms is based on descent from someone to whom arms were granted by the official heraldic authorities of a sovereign country and that one must prove descent, usually in the male line, from the specific ancestor to whom the arms were granted or, for some countries of Eastern Europe, a specific family group usually called a clan! But even in a case where research leads to ancestral arms, the claim will remain a historical one unless the country where the arms originated recognizes the claim, or the country where the claimant may now be living is able to confirm the entitlement based on solid documentation and possibly make the confirmation official.

Prior to the establishment of the Canadian Heraldic Authority in 1988, officers of the Crown in England or Scotland made grants to Canadian citizens, municipalities and a few other corporate bodies. [13] There is no doubt that these grants are legal and valid in Canada even after 1988. But many other Canadians bear arms from Europe for which the entitlement is no longer clear for various reasons such as: a change from a monarchy to a republic in the country of origin, the loss of documentation, or variances introduced over the years in the depiction of the arms. In Canada, it would be important to have these arms confirmed by the Canadian Heraldic Authority, even if a new Canadian grant with differences might be required. In fact, even when the entitlement can be easily proven, it seems important to register the arms in Canada so that descendants will have a clear record in the country where they live.

A Double-edged Instrument

Symbols appeal to patriotism because they embody the very essence of a nation. Some people shed tears when a flag is raised. Flags bring people together in both times of joy and tragedy. As instruments that arouse strong emotions, symbols can be used to serve good causes as well as bad ones. The latter may take the form of aggressive nationalism, domination, subjugation and persecution. Sects are masters at using symbolism such as impressive insignia patterned on orders of chivalry. Amazingly they are able to bring highly educated and intelligent people to believe in myths just as fantastic as those that have come to us from the past.

On a national level, we often think of Nazi Germany and its impressive array of flags and insignia that make the joy of some collectors today. Napoleon I was the heir of a revolution that he turned into a regime dedicated largely to his own imperial glory. For some he is a hero and a great liberator; for others he is a man who upset everything and did more harm than good. It is interesting that, although the revolution had abolished nobility and all its trappings including the use of coats of arms, Napoleon re-established his own nobility, a system of honours known as the Légion d’honneur, and his own heraldic system. The French have a saying relating to revolution: “Plus ça change; plus ça demeure le même”— “The more it changes; the more it remains the same”.

As a reflection of the essence of a nation, heraldry is frequently used in a derogatory manner within caricatures. A large engraved cartoon entitled “British Resentment or the French fairly coopt at Louisbourg” published in London in 1755 is full of heraldic allusions. The moon bearing the royal arms of Great Britain is seen eclipsing the sun bearing the fleurs-de-lis of France. A lily is wilting at the side of a thriving rose, the British lion dominates the map of North America, the motto of Scotland Nemo Me Impune Lacessit (No one will assail me with impunity) is displayed above a dais lodging Britannia with Neptune beside her, flying the Union Flag from his trident. [14] We have all seen the maple leaf or fleur-de-lis upside down in one caricature or another or the arms of Canada developed into a grotesque concoction.

Symbols appeal to patriotism because they embody the very essence of a nation. Some people shed tears when a flag is raised. Flags bring people together in both times of joy and tragedy. As instruments that arouse strong emotions, symbols can be used to serve good causes as well as bad ones. The latter may take the form of aggressive nationalism, domination, subjugation and persecution. Sects are masters at using symbolism such as impressive insignia patterned on orders of chivalry. Amazingly they are able to bring highly educated and intelligent people to believe in myths just as fantastic as those that have come to us from the past.

On a national level, we often think of Nazi Germany and its impressive array of flags and insignia that make the joy of some collectors today. Napoleon I was the heir of a revolution that he turned into a regime dedicated largely to his own imperial glory. For some he is a hero and a great liberator; for others he is a man who upset everything and did more harm than good. It is interesting that, although the revolution had abolished nobility and all its trappings including the use of coats of arms, Napoleon re-established his own nobility, a system of honours known as the Légion d’honneur, and his own heraldic system. The French have a saying relating to revolution: “Plus ça change; plus ça demeure le même”— “The more it changes; the more it remains the same”.

As a reflection of the essence of a nation, heraldry is frequently used in a derogatory manner within caricatures. A large engraved cartoon entitled “British Resentment or the French fairly coopt at Louisbourg” published in London in 1755 is full of heraldic allusions. The moon bearing the royal arms of Great Britain is seen eclipsing the sun bearing the fleurs-de-lis of France. A lily is wilting at the side of a thriving rose, the British lion dominates the map of North America, the motto of Scotland Nemo Me Impune Lacessit (No one will assail me with impunity) is displayed above a dais lodging Britannia with Neptune beside her, flying the Union Flag from his trident. [14] We have all seen the maple leaf or fleur-de-lis upside down in one caricature or another or the arms of Canada developed into a grotesque concoction.

|

Medal struck in 1759 to celebrate the success of British troops in North America. The inverted fleur-de-lis is surrounded by the Latin inscription PERFIDIA INVERSA, “the perfidious overthrown.” Library and Archives Canada, negative C 62216.

|

On the obverse King George II appears to be smiling. L Library and Archives Canada, negative C 62215.

|

When a new emblem is being created or changes are made to an old one, it is normal that the emblem itself be made fun of in caricature. This happened to the Pearson Pennant and to the present flag during the debates that led to its adoption. It also took place when the motto of the Order of Canada was added to the arms of Canada in 1994. It frequently occurs when a municipality adopts new arms or changes older ones. An entirely suitable, beautiful and heraldically correct design can be rejected by the population because of derision by cartoonists and journalists, but this is inevitable in a democratic system.

Because heraldic insignia represents people collectively, they often appear in cartoons to show opposition, poke fun at, ridicule or condemn actions or ideas, usually of a political nature. This use of heraldry within a context of humorous diatribes or ridicule is considered fair game. Editorial cartoonists are professionals in this respect and it is not in their interest to look petty, vindictive, unfair or overly partisan. Their distortion of symbols is normally done in a humorous and clever way to get a point across rather than convey hate or scorn for the symbols themselves.

Sometimes, however, insults to national emblems can take the form of desecration such as flag burning, spitting or walking on a flag and worst. Such manifestations have unfortunately taken place in Canada against the Maple Leaf Flag or the Fleurdelisé to show opposition to the federal government or the independence movement in Quebec. In such cases, protesters fail to keep in mind that these flags do not represent a particular political orientation, or a party in power, but people collectively. In Quebec the Fleurdelisé is a provincial flag and represents everyone living in that province, though it is sometimes viewed as an exclusively francophone or even a separatist flag. Attacks on flags only exacerbate distrust and hatred and serve no constructive purpose. Fortunately they remain rare manifestations that most Canadians deplore.

Cultural diversity, including the presence of minority flags, is generally accepted. The Métis of the West are represented by a blue and a red flag both bearing a white infinity sign. In the Maritime Provinces, the Acadian tricolour adopted in 1884 and granted to the Société nationale de l’Acadie by the Canadian Heraldic Authority in 1995 is proudly flown. The Newfoundland and Labrador Francophone Federation was granted full arms and a flag by the Canadian Heraldic Authority in 2004, based on a flag it flew since 1986. The francophone minorities of Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia, Yukon and Northwest Territories have all adopted their own flag. [15] These groups are cultural and perhaps political entities, but not necessarily legal entities. If such minorities wanted to make their flags official, the Chief Herald would have to decide if the flags are “grantable”, but if a grant was made in original or modified form, it would have to be made to a society or association having a corporate status and not to a cultural group. For example, the Comité d’action francophone Pontiac was granted a flag by the Canadian Heraldic Authority in the year 2000 as a registered corporate body.

Because heraldic insignia represents people collectively, they often appear in cartoons to show opposition, poke fun at, ridicule or condemn actions or ideas, usually of a political nature. This use of heraldry within a context of humorous diatribes or ridicule is considered fair game. Editorial cartoonists are professionals in this respect and it is not in their interest to look petty, vindictive, unfair or overly partisan. Their distortion of symbols is normally done in a humorous and clever way to get a point across rather than convey hate or scorn for the symbols themselves.

Sometimes, however, insults to national emblems can take the form of desecration such as flag burning, spitting or walking on a flag and worst. Such manifestations have unfortunately taken place in Canada against the Maple Leaf Flag or the Fleurdelisé to show opposition to the federal government or the independence movement in Quebec. In such cases, protesters fail to keep in mind that these flags do not represent a particular political orientation, or a party in power, but people collectively. In Quebec the Fleurdelisé is a provincial flag and represents everyone living in that province, though it is sometimes viewed as an exclusively francophone or even a separatist flag. Attacks on flags only exacerbate distrust and hatred and serve no constructive purpose. Fortunately they remain rare manifestations that most Canadians deplore.

Cultural diversity, including the presence of minority flags, is generally accepted. The Métis of the West are represented by a blue and a red flag both bearing a white infinity sign. In the Maritime Provinces, the Acadian tricolour adopted in 1884 and granted to the Société nationale de l’Acadie by the Canadian Heraldic Authority in 1995 is proudly flown. The Newfoundland and Labrador Francophone Federation was granted full arms and a flag by the Canadian Heraldic Authority in 2004, based on a flag it flew since 1986. The francophone minorities of Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia, Yukon and Northwest Territories have all adopted their own flag. [15] These groups are cultural and perhaps political entities, but not necessarily legal entities. If such minorities wanted to make their flags official, the Chief Herald would have to decide if the flags are “grantable”, but if a grant was made in original or modified form, it would have to be made to a society or association having a corporate status and not to a cultural group. For example, the Comité d’action francophone Pontiac was granted a flag by the Canadian Heraldic Authority in the year 2000 as a registered corporate body.

****

Some people have little or no interest in heraldry in the same way that others have no appreciation of modern art or opera. Their personal approach to life is such that they have no exposure to or taste for such things. Like the general public, the majority of historians and archivists have no special interest in heraldry. Historians who have encountered heraldry perhaps when writing a biography or verifying the authenticity of the titles used by an historical figure often have great respect for the field without necessarily making it an area of study. The same respect is found among archivists and museologists who work with medals or old maps illustrated with arms, and who have seen the importance of heraldry for the identification and dating of documents and artefacts. After these initial contacts, some make it a domain of specialization. Other professionals not only remain aloof from heraldry, but for some reason, choose to treat it with open contempt. One of the aims of this work is to change such attitudes that sometimes belong to one generation but not necessarily to the next. It is hoped, at least, that the readers of this chapter will become more aware of the heraldry they encounter in their daily lives.

In this chapter we have looked at several less brilliant manifestations of heraldry. A number of the illustrations belong to the domain of popular heraldry and are not always commendable artistically, although such spontaneous manifestations are part of our history and have helped keep interest alive until the country decided to choose a more disciplined approach. The next chapter deals with heraldry’s struggle to keep its traditional place as it confronts the rising tide of the modern logo.

In this chapter we have looked at several less brilliant manifestations of heraldry. A number of the illustrations belong to the domain of popular heraldry and are not always commendable artistically, although such spontaneous manifestations are part of our history and have helped keep interest alive until the country decided to choose a more disciplined approach. The next chapter deals with heraldry’s struggle to keep its traditional place as it confronts the rising tide of the modern logo.

Notes

[1] My wife and I have collected over 1100 Canadian heraldic ceramic items, including a few complete tea sets, which we donated to the Canadian Museum of History.

[2] Auguste Vachon, “La céramique armoriée d’importation, reflet du nationalisme canadien (1887-1921),” Genealogica & Heraldica: Proceedings of the 22nd International Congress of Genealogical and Heraldic Sciences in Ottawa, August 18-23, 1996 (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1998), 485-86.

[3] Lyman’s Standard Catalogue of Canada-BNA Postage Stamps, 34th ed. (Toronto: The Charlton Press, 1982), 30, 121.

[4] Most of this information is found on the website of the National Currency Museum of the Bank of Canada: http://www.currencymuseum.ca/ (accessed 7 January 1915); The Charlton Standard Catalogue of Canadian Coins, 45th ed. (Toronto: The Charlton Press, 1991), 2-11, 15-19, 183.

[5] V. Molchanov, “Heraldry — a design of the times,” Pravda (English edition), October, 1987; Heraldry in Canada / L’Héraldique au Canada, 22 (June 1988), 1.

[6] Colby Cosh, “A coat to fit Quebec” in Alberta Report, 25 Dec. 1995, 9; Robert Pichette, “The ignorant tilt at francophone windmills: The moribund CoR ranks have been firing missives both misguided and misinformed” in Saint John Telegraph Journal, 1 March 1996, A11 (CoR is the New Brunswick Confederation of Regions Party); Diane Francis, “Crest change a sellout to separatists” in Saskatoon Star-Phoenix, 5 Sept. 1996, A2.

[7] “From the Editors Desk: is Canada’s coat of arms becoming meaningless?” in Heraldry in Canada / LHéraldique au Canada, 5 (March 1971), 31.

[8] Edward Greenspon, “Reform outraged by secret in Canada’s coat of arms,” Globe and Mail, 6 December 1995, A1-2; Jules Richer, “Le Reform soulève une tempête aux Communes,” Le Soleil, 6 Dec. 1995, 14.

[9] Halvor Moorshead, “How to Get a Real Coat of Arms!” and “Acquiring a Real Coat of Arms,” Family Chronicle, (Sept/Oct. 2003), 27-31 and (Nov./Dec. 2003), 27-29. See also: http://www.familychronicle.com/CoatofArms1.htm; http://www.familychronicle.com/CoatofArms2.htm; http://www.familychronicle.com/CoatofArms3.htm. (accessed 7 January 2015).

[10] George Way of Plean and Romilly Squire, Scottish, Clan & Family Encyclopedia (Glasgow: Harper Collins, 1994), 29-30, 46.

[11] http://www.archivesdefrance.culture.gouv.fr/archives-publiques/organisation-du-reseau-des-archives-en-france/commission-nationale-d-heraldique/ (accessed 7 January 2015).

[12] “A not so Amazing Story,” Heraldry in Canada / LHéraldique au Canada, 20 (June 1986), 33.

[13] Before the establishment of the Canadian Heraldic Authority in 1988, most municipalities obtained their arms from amateur artists as described in chapter III. Most of these were of a popular, folk art type and not the best heraldry. The designs that respected the laws of heraldry were few. The first official municipal grant was to the City of Westmount by the Lord Lyon King of Arms in 1945. By the time the Heraldry Society of Canada was founded in October 1966, the number of lawful municipal grants was 25 and, by 1988, when the Canadian Heraldic Authority was established, 84 Canadian municipalities had received grants from the College of Arms or the Court of the Lord Lyon. Harold A. Diceman, “Municipal Heraldry,” Heraldry in Canada / LHéraldique au Canada, 3 (June 1969): 24-25; Ian L. Campbell, The Identifying Symbols of Canadian Institutions, Part III, The Identifying Symbols of Canadian Municipalities, vol. 2 (Waterloo: Canadian Heraldry Associates, 1990), 20-21.

[14] This engraving can be viewed on many websites by using its title.

[15] Hélène-Andrée Bizier and Claude Paulette, Fleur de lys d’hier à aujourd’hui (Montréal : Éditions Art Global, 1997), 144.

[1] My wife and I have collected over 1100 Canadian heraldic ceramic items, including a few complete tea sets, which we donated to the Canadian Museum of History.

[2] Auguste Vachon, “La céramique armoriée d’importation, reflet du nationalisme canadien (1887-1921),” Genealogica & Heraldica: Proceedings of the 22nd International Congress of Genealogical and Heraldic Sciences in Ottawa, August 18-23, 1996 (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1998), 485-86.

[3] Lyman’s Standard Catalogue of Canada-BNA Postage Stamps, 34th ed. (Toronto: The Charlton Press, 1982), 30, 121.

[4] Most of this information is found on the website of the National Currency Museum of the Bank of Canada: http://www.currencymuseum.ca/ (accessed 7 January 1915); The Charlton Standard Catalogue of Canadian Coins, 45th ed. (Toronto: The Charlton Press, 1991), 2-11, 15-19, 183.

[5] V. Molchanov, “Heraldry — a design of the times,” Pravda (English edition), October, 1987; Heraldry in Canada / L’Héraldique au Canada, 22 (June 1988), 1.

[6] Colby Cosh, “A coat to fit Quebec” in Alberta Report, 25 Dec. 1995, 9; Robert Pichette, “The ignorant tilt at francophone windmills: The moribund CoR ranks have been firing missives both misguided and misinformed” in Saint John Telegraph Journal, 1 March 1996, A11 (CoR is the New Brunswick Confederation of Regions Party); Diane Francis, “Crest change a sellout to separatists” in Saskatoon Star-Phoenix, 5 Sept. 1996, A2.

[7] “From the Editors Desk: is Canada’s coat of arms becoming meaningless?” in Heraldry in Canada / LHéraldique au Canada, 5 (March 1971), 31.

[8] Edward Greenspon, “Reform outraged by secret in Canada’s coat of arms,” Globe and Mail, 6 December 1995, A1-2; Jules Richer, “Le Reform soulève une tempête aux Communes,” Le Soleil, 6 Dec. 1995, 14.

[9] Halvor Moorshead, “How to Get a Real Coat of Arms!” and “Acquiring a Real Coat of Arms,” Family Chronicle, (Sept/Oct. 2003), 27-31 and (Nov./Dec. 2003), 27-29. See also: http://www.familychronicle.com/CoatofArms1.htm; http://www.familychronicle.com/CoatofArms2.htm; http://www.familychronicle.com/CoatofArms3.htm. (accessed 7 January 2015).

[10] George Way of Plean and Romilly Squire, Scottish, Clan & Family Encyclopedia (Glasgow: Harper Collins, 1994), 29-30, 46.

[11] http://www.archivesdefrance.culture.gouv.fr/archives-publiques/organisation-du-reseau-des-archives-en-france/commission-nationale-d-heraldique/ (accessed 7 January 2015).

[12] “A not so Amazing Story,” Heraldry in Canada / LHéraldique au Canada, 20 (June 1986), 33.