Royalty Mingling with Beavers and Maple Leaves

Auguste Vachon, Outaouais Herald Emeritus

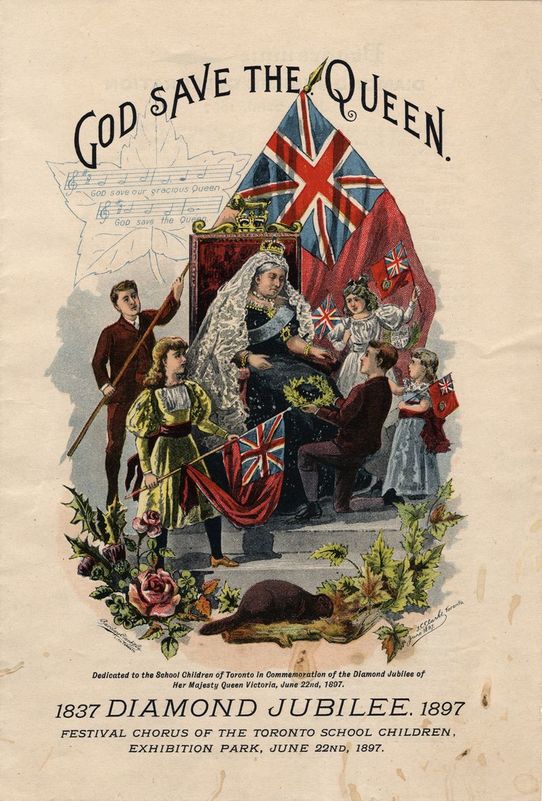

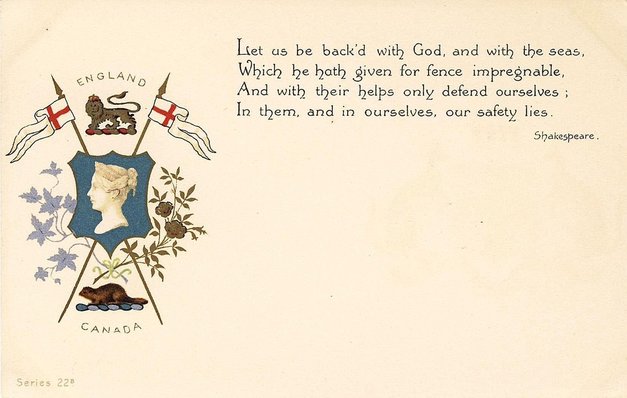

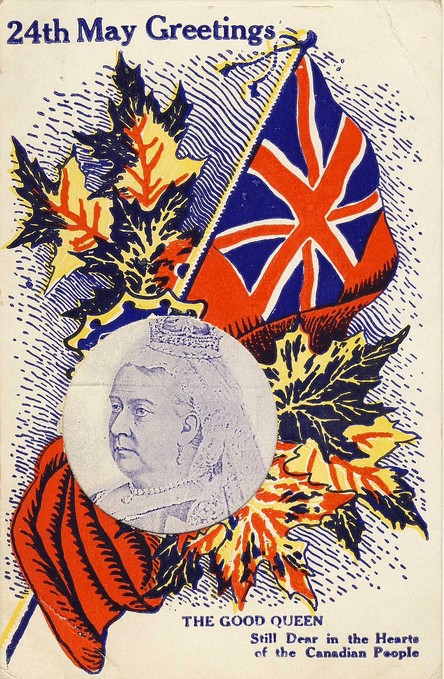

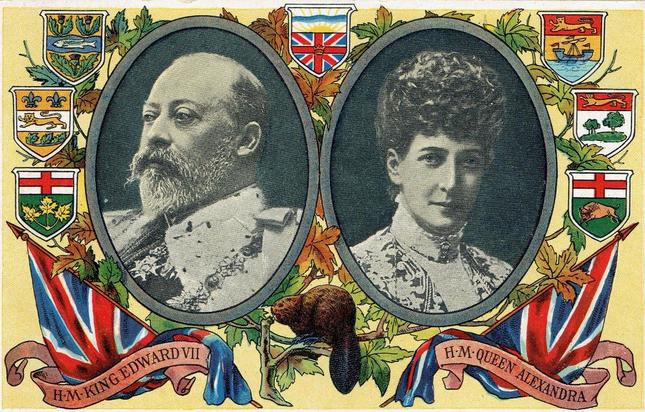

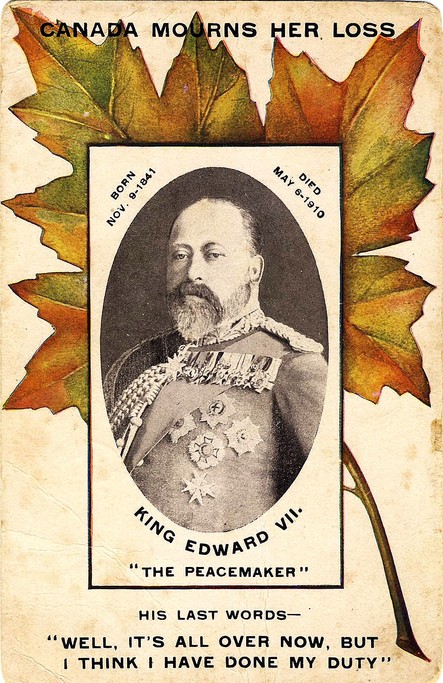

Canadian ceramic ware and postcards provide the most abundant imagery where royalty is depicted with beavers or maple leaves and sometimes both. This trend goes back a few years before the effigies of British royals began appearing on ceramic pieces or postcards made specifically for Canada rather than for the empire as a whole (figs. 2 and 3). Recurrent themes are the loyalty of Canadians to the British Crown as well as an unflinching attachment to Canada where they live. Several of the illustrations presented here are essentially folk art documenting the depiction of royalty in popular imagery, a subject which offers a vast area of investigation at the level of the British Empire or Commonwealth. Looking briefly at Canada alone, we see that J. Russell Harper’s work A people’s Art (University of Toronto Press, 1974) includes a portrait of King George III (p. 55) and one of Queen Victoria (p. 61).

Juxtaposing sovereigns with maple leaves seems as suitable as linking emperors with laurel, but the beaver does not appear to fit as well in the entourage of royalty as does the British lion. It is a rodent with admirable qualities, but still a rodent with the looks of a member of the order Rodentia, hardly an order of knighthood. In the more recent ceramic pieces commemorating royal visits to Canada or coronations, the beaver is no longer seen.

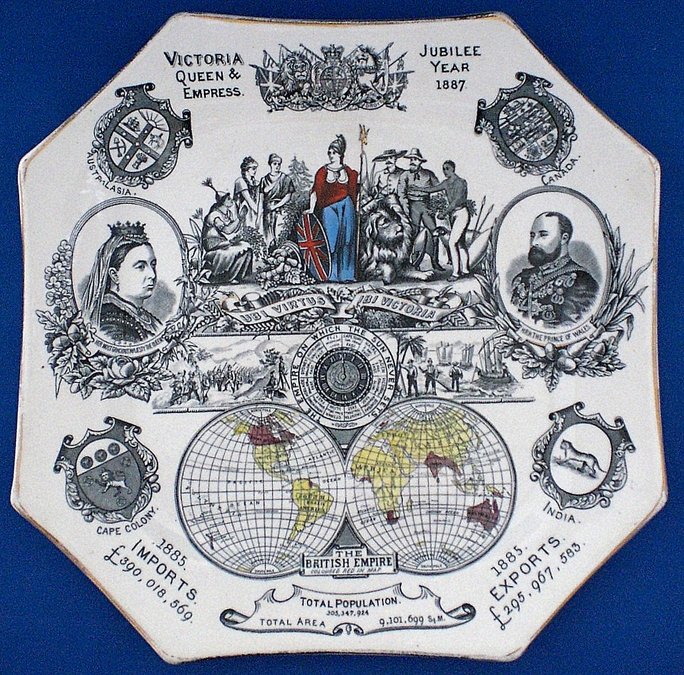

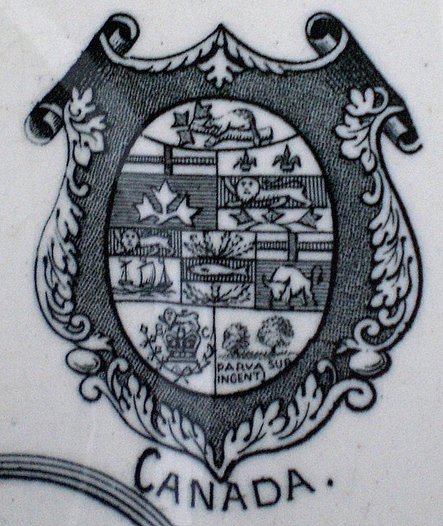

Some of the imagery at the time of Queen Victoria seems a little overdone, somewhat too busy (figs. 1- 4). I expected a more sober treatment on recent items. This has occurred to some extent for King George VI (figs. 12-14) and Queen Elizabeth II (figs. 16-17, 20), but some of the more recent souvenirs are just as charged as the earlier ones (figs. 15, 18, 21).

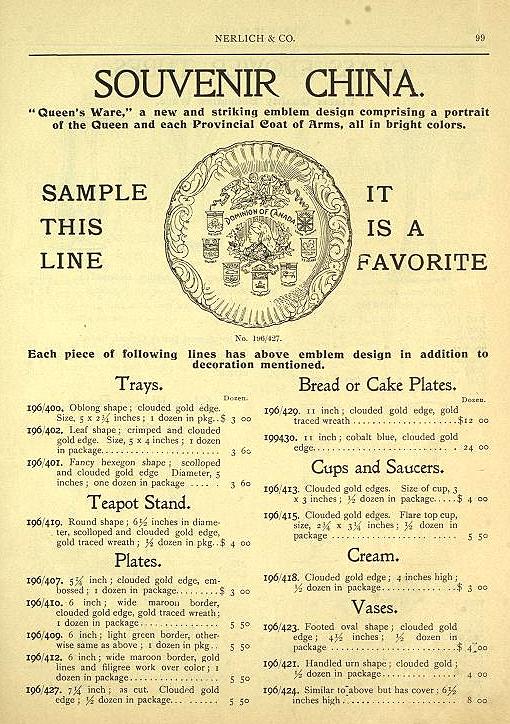

The way of depicting one’s attachment to royalty reflects the mentality of a given period. Placing the royal effigies on teapots, cups and saucers, pitchers, shaving beakers, cigarette boxes, and beer mugs is a fairly common practice and seems perfectly acceptable. On the other hand, placing food over a royal portrait seems inappropriate, at least to some of us today. This was evidently not always the case. The page from the Nerlich catalogue mentioned with figures 4 & 5 includes bread or cake plates as well as side plates. This means that food was not only placed on the effigy of Queen Victoria, but that someone eating cake from one of these plates would have touched or even scraped her portrait with a spoon or fork. Royal portraits have appeared inside sugar bowls, which gives the impression that covering royalty with sugar is a sweet gesture. However, placing royal portraits within a cup’s bowl to receive boiling tea or coffee seems a little harsh [see examples in Zeder, British Royal Commemoratives with Prices (1986), p. 85 and Davey and Mannion, Four Generations of Royal Commemorative China 1936-1990 (1991), p. 101, no. 712]. Sometimes the effigies of the sovereigns are featured inside ashtrays, a practice which is surely the height of bad taste at any time (see caption with fig. 17).

Juxtaposing sovereigns with maple leaves seems as suitable as linking emperors with laurel, but the beaver does not appear to fit as well in the entourage of royalty as does the British lion. It is a rodent with admirable qualities, but still a rodent with the looks of a member of the order Rodentia, hardly an order of knighthood. In the more recent ceramic pieces commemorating royal visits to Canada or coronations, the beaver is no longer seen.

Some of the imagery at the time of Queen Victoria seems a little overdone, somewhat too busy (figs. 1- 4). I expected a more sober treatment on recent items. This has occurred to some extent for King George VI (figs. 12-14) and Queen Elizabeth II (figs. 16-17, 20), but some of the more recent souvenirs are just as charged as the earlier ones (figs. 15, 18, 21).

The way of depicting one’s attachment to royalty reflects the mentality of a given period. Placing the royal effigies on teapots, cups and saucers, pitchers, shaving beakers, cigarette boxes, and beer mugs is a fairly common practice and seems perfectly acceptable. On the other hand, placing food over a royal portrait seems inappropriate, at least to some of us today. This was evidently not always the case. The page from the Nerlich catalogue mentioned with figures 4 & 5 includes bread or cake plates as well as side plates. This means that food was not only placed on the effigy of Queen Victoria, but that someone eating cake from one of these plates would have touched or even scraped her portrait with a spoon or fork. Royal portraits have appeared inside sugar bowls, which gives the impression that covering royalty with sugar is a sweet gesture. However, placing royal portraits within a cup’s bowl to receive boiling tea or coffee seems a little harsh [see examples in Zeder, British Royal Commemoratives with Prices (1986), p. 85 and Davey and Mannion, Four Generations of Royal Commemorative China 1936-1990 (1991), p. 101, no. 712]. Sometimes the effigies of the sovereigns are featured inside ashtrays, a practice which is surely the height of bad taste at any time (see caption with fig. 17).

N.B.

The postcards belong to Auguste and Paula Vachon. The ceramics objects are now part of the Vachon Collection of the Canadian Museum of History. The photographs were taken before donating the collection to the museum.

The postcards belong to Auguste and Paula Vachon. The ceramics objects are now part of the Vachon Collection of the Canadian Museum of History. The photographs were taken before donating the collection to the museum.

1. This plate shows the British Empire on which the sun never sets. Though a bit indirectly, it connects Queen Victoria and her son Edward Prince of Wales with maple leaves in the Dominion shield, namely in the arms of Ontario and Quebec seen at the top and the beaver on a maple log added above the shield (see detail). Although the empire as a whole is represented, the beaver and maple leaves have their corner within the realm. Plate by Wallis Gimson, 1887.

2. Front cover of the programme of a musical event held at Exhibition Park on 22 June 1897. The smaller print reads: “Dedicated to the School Children of Toronto in Commemoration of the Diamond Jubilee of Her Majesty Queen Victoria, June 22nd, 1897. This image allies royalty with strong Canadian symbolism. Queen Victoria is surrounded by school children holding one Union Flag (Jack) and four Red Ensigns, two of which have the Dominion shield in the fly. A maple leaf to the left of the queen is inscribed with some lines and music of “God save the Queen.” Below the throne, which is topped by the royal crown and lion, the traditional beaver on his log is seen between, on the left, a spray of roses (England), thistles (Scotland) and shamrocks (Ireland) and, on the right, a spray of maple leaves. The image is signed by the artist “J.C. Clarke, Toronto, June 1897.” and is printed by Barclay, Clark & Co., lithographers of Toronto. In other words, it is Canadian-made imagery for Canadians. The theme is reminiscent of what appears on some of the ceramic pieces and postcards that follow. The programme is part of the Baldwin Room Collection of the Toronto Reference Library.

3. This lithograph entitled “Her Majesty Queen Victoria's diamond jubilee, 1837-1897” features Canada depicted as a youthful figure paying homage to the queen. The youth is crowned with a wreath of maple leaves, holds a Red Ensign, and is accompanied by a beaver with a sprig of maple in the mouth. This imagery, like figure 2, is made in Canada and echoes what latter appears on ceramic pieces and postcards as in figures 4, 6 and 7. Toronto Lithographing Company, Library and Archives Canada, Accession No. 1964-99-1, C-039048.

4. The effigy of Queen Victoria is within branches of maple with a beaver below, surrounded by the shield of arms of the provinces as they were depicted around 1900 when the plate was made. This item was advertised in the 1900-1901 wholesale catalogue of Nerlich & Co. of Toronto (fig. 5). Underneath, the plate is inscribed “Regd No 1900” which corresponds to the date when the plate was manufactured. The Nerlich catalogue lists 17 items with this same imagery. At least three other series were produced: one where the central image is surrounded by a wreath of oak leaves, one bordered in cobalt blue and one in reddish-brown, yellow, and green tints.

5. Figure 4 is part of this ensemble advertized by Nerlich & Co. Though described as souvenir china, the pieces were sold wholesale by the dozen to be retailed by other merchants as utility sets or individually as souvenirs. The advertisement specifies “Queen’s Ware” which should not be confused with the cream coloured pottery called Queen's Ware produced by Wedgwood. The pieces sold by Nerlich are hard-paste porcelain and were likely made by Schmidt & Co., Altrohlau (Bohemia), Austria, now Stará Role, Czech Republic. This will be the subject of a future article on heraldic souvenirs imported by Nerlich & Co. The page is from the Nerlich & Co. Illustrated Catalogue. Fall and Holiday, Trade Season 1900-1901, Toronto, p. 99. The catalogue belongs to the Toronto Public Library, see: https://archive.org/details/fallandholiday00nerluoft (accessed 27 March 2017).

6. Queen Victoria is the noble company of the lion, the rose and the cross of St. George representing England, and the maple leaves and beaver symbolizing Canada. Postcard by C.W. Faulkner & Co., London, England.

7. The effigy of Queen Victoria is placed over the Red Ensign and a spray of maple leaves. The postcard is inscribed “S.B.” (Stedman Bros. Ltd. of Brantford) and is postdated December 1908.

8. A well-fed beaver on a maple bough with several leaved ramifications is seen between two Union Jacks. The armorial shields are Nova Scotia, Quebec and Ontario on the left, British Columbia (unofficial in centre) New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Manitoba (unofficial) on the right. From the shields, the image can be dated 1905. Postcard by Prudential Insurance Company of America, Newark, New Jersey, USA.

8a. The imagery is self-explanatory, but the inscription raises a fine point of English usage. “Canada mourns her loss” is not a mistake but an archaic form. Today we would expect “Canada mourns its loss,” but formerly the name of countries were viewed as feminine. Consider these lines from Robert Ernest Vernède’s 1914 poem To our Fallen: “But God grants your dear England / A strength that shall not cease / Till she have won for all the Earth.” The tense of “she have won” is subjunctive perfect, see: http://www.verbix.com/webverbix/English/win.html (accessed 27 March 2017). Postcard by A.H. Cooper, Toronto, postdated 10 August 1910.

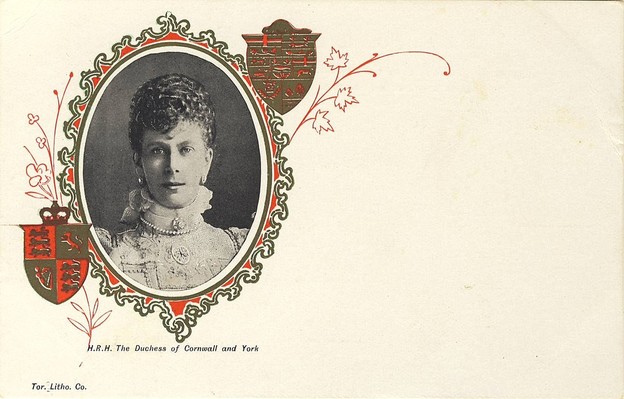

9. The portrait in miniature format of Her Royal Highness the Duchess of Cornwall and York. The postcard seems to commemorate her 1901 visit to Canada with her husband Prince George Frederick Ernest Albert, Duke of Cornwall and York, second son of Edward VII and Queen Alexandra. He later reigned as George V (1910-1936) after the death of his brother, Prince Albert Victor. The Duchess reigned as Queen Mary (fig. 10) and was also called Mary of Tech in reference to her title as Princess of Tech of the Kingdom of Württemberg. A delicate branch of maple is seen on the right along with a beaver topping the Dominion shield, something which was added in some depictions.

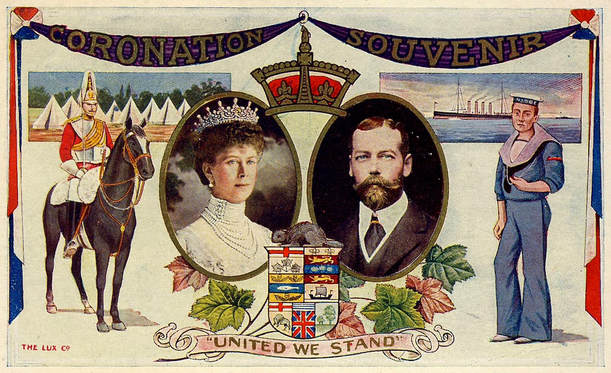

9a. Another example of mixing Canadian symbols, including the beaver and maple leaves, on this coronation souvenir of George V and Queen Mary, 22 June 1911. Postcard “Designed and printed in Canada. Published by the LUX Co. and printed by the Thomson Stationery Co., Ltd., Vancouver B.C.”

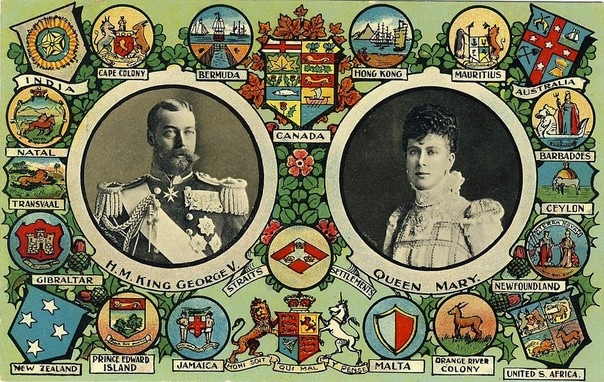

10. The shield of the Dominion is placed on a large cluster of maple between the king and queen. The badge of Newfoundland and the arms of Prince Edward Island are included among the devices of other British dependencies. Postcard in the National Series by Millar & Lang Art Publishing Co. (M & L, Ltd.), Glasgow, Scotland and London, England.

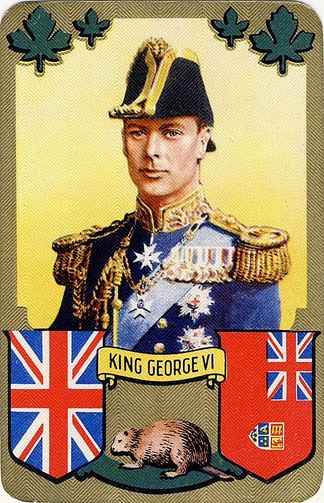

11. The portraits of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth on playing cards. A well-fed beaver is lodged between the Union Jack and the Canadian Red Ensign while green maple leaves adorn the upper corners. This is a flagrant example of popular art.

12. Bone china side plate by John Aynsley & Son, England, commemorating the visit of George VI and Queen Elizabeth to Canada and the United States in 1939. Shows Niagara Falls and the central block of the Parliament Buildings. A three-leaved sprig of maple is seen under the royal portraits and the whole is enclosed within a wreath of maple leaves. What emanates from the Union Jack on the right and the Canadian Blue Ensign on the left appears to be grape vines, but maple leaves were likely intended because the depiction of the leaves is the same as on the sprig and wreath. Moreover on a number of souvenirs, maple leaves are depicted on vines with spirally tendrils for decorative effect, see figure 14.

13. Plate by Wood and Sons, England, commemorating the visit of George VI and Queen Elizabeth to Canada and the United States in 1939. The centre block of the Canadian Parliament Buildings on the right is accompanied by the Capitol of the United States on the left. The flags are, on the right, the Canadian Blue Ensign with the cross of St. Andrew (Scotland) behind; on the left, the Union Jack with a white saltire cross on red behind (?); in the base, the Stars and Stripes or Old Glory of the United States. Garlands of maple leaves are featured with the king and queen and with the inscription at the top.

14. Plate by Grimwades (Royal Winton), England, commemorating the visit of George VI and Queen Elizabeth to Canada in 1939. Inscribed “MADE EXPRESSLY FOR NERLICH & CO; TORONTO.” The maple leaves on the border have curly tendrils like vines which are for decorative effect since the maple leaf, emblem of Canada, is obviously intended.

15. Maple leaves are present within the inner circle and with the inscription above along with roses, thistles and shamrocks. Plate by John Maddock & Sons, England. A similar design was made by the same company for the 1939 royal visit to the United States and another with the portrait of Queen Elizabeth II, see M. H. Davey and D. J. Mannion, Four Generations of Royal Commemorative China 1936-1990, (Hemmel Hampstead [Hertfordshire]: Dayman Publications, 1991) pp. 16, 98.

16. A Clarice Cliff design commemorating the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. The central portrait is a photograph by Yousuf Karsh. The arms of Quebec are those of 1868 rather than the ones with three fleurs-de-lis adopted by the province in 1939. Since 3 February 1953, the titles of Queen Elizabeth II included that of Queen of Canada. The royal arms of Canada rather than those of the United Kingdom could have been displayed at the top of the plate. By Arthur J. Wilkinson Ltd; Royal Staffordshire Pottery, England, part of the "Confederation Series Canada".

17. This souvenir of the 1959 visit to Canada of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip features the royal couple on a large maple leaf. This imagery was repeated on many souvenirs produced by such English companies as Arthur Wood, Hudson & Middleton, the Co-operative Wholesale Society (Windsor), Shore & Coggins (Queen Anne). This piece by Arthur Wood could serve as an ashtray or pin dish. Although in very poor taste, placing the portraits of Their Majesties in centre of ashtrays was not that uncommon, see for instance Audrey B. Zeder, British Royal Commemoratives with Prices, (Lombard [Illinois]: Wallace-Homestead Book Company,1986, pp. 66, 82.

18. Souvenir commissioned by the Monarchist League of Canada to commemorate the 1977 Silver Jubilee of H.M. Queen Elizabeth II and her visit to Canada that year. The names of provinces are featured on both sides on a wreath of maple leaves. Maple leaves also appear with the dates, in the arms of Canada at the top and one leaf on the insignia of the Order of Canada in base. A limited edition of 500, designed by A. Kitson Towler, produced by Mercian China; Burton-upon--Trent, England. Similar Jubilee plates were produced in England, one showing the queen with the prime ministers, another with the Law Lords (Lords of Appeal in Ordinary), and one with other sovereigns of the world.

19. An abundance of maple leaves adorn this plate dedicated to the transfer of the Canadian Constitution from Great Britain to Canada on 17 April 1982, an event termed the patriation of the Constitution. The outer rim is inscribed “TO COMMEMORATE THE VISIT OF H.M. THE QUEEN OF CANADA TO SIGN THE PATRIATION OF THE CANADIAN CONSTITUTION” and the inner rim “EN SOUVENIR DE LA VISITE DE SA MAJESTÉ ROYALE LA REINE DU CANADA POUR SIGNER LA (should be LE instead of LA) RAPATRIEMENT DE LA CONSTITUTION CANADIENNE.” A Limited Edition of 1000 plates designed by John Ball, manufactured by Caverswall, England.

20. An attractive memento to the “patriation” of the Canadian Constitution in 1982, with a frieze of maple leaves around the base and two leaves on the handle. Wedgwood, England.

21. Five red maple leaves adorn this souvenir of the 40th anniversary of accession of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II to the throne and the 125th anniversary of the Confederation of Canada. At the top, the full Arms of Canada are inscribed on either side “1867-1992” although they are the arms of Canada as granted in 1921 and modified in 1923 and 1957, see: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/arms-of-canada.html. The images from right to left are: the Parliament Buildings, Ottawa; City Hall, Kingston; Niagara Falls and Banff National Park. Produced exclusively for Peter Jones China Wakefield, in a limited edition of 5000 designed by John Ball. Manufactured by the famous manufacturer of heraldic souvenirs, Goss China, England.