Why Three National Symbols of Sovereignty for Canada?

Auguste Vachon, Outaouais Herald Emeritus

Canada has three national symbols of sovereignty which express its supreme authority as an independent country, both nationally and internationally, namely a flag, a coat of arms and a great seal. The international scope of the flag is obvious, but the coat of arms also has international uses, for instance on one’s passport and in connexion with international treaties. The great seal likewise has international applications when affixed to the commissions of ambassadors and regular members of permanent international commissions.

The wording “national symbols of sovereignty” was chosen based on several considerations. The expression “symbols of sovereignty” appears in the title of both Conrad Swan’s Canada: Symbols of Sovereignty (1977) and Brian Barker’s work The Symbols of Sovereignty (1979). The qualifier “national” is added to underline their link with the country as a whole. There are many symbols of sovereignty within a country, but they do not all have the same scope. The authority expressed by the mace of the House of Commons and that of the Senate does not extend outside Parliament, although the two chambers together enact laws with national and sometimes international implications. Issuing currency and stamps are signs of sovereignty, but not to the same degree as the national symbols described here, even if stamps are used both nationally and internationally. Using the expressions “national symbols” or “state symbols” without the qualifier “sovereign” does not seem complete. The beaver is a national or state symbol of Canada but serves more to express identity than sovereignty. The flag, coat of arms and great seal of a country translate into concrete applications such abstract notions as sovereignty, national independence, self-government and public authority.

The most authoritative work on the matter is Conrad Swan’s Canada: Symbols of Sovereignty in which he designates such symbols “as the expression of principles of constitutional as well as international law” (see his preface). Yet a seldom raised question is, Why Canada has three symbols instead of just one? The obvious answer is that they each serve a different purpose, but clarifying the nature of these different functions is complex. What follows is an attempt to explain in simple terms some of these distinctions. Because the subject retains many complexities, links are included to websites where the reader can find additional information. The essential points are also summarized in a section entitled “In a Nutshell” at the end of the analysis.

The wording “national symbols of sovereignty” was chosen based on several considerations. The expression “symbols of sovereignty” appears in the title of both Conrad Swan’s Canada: Symbols of Sovereignty (1977) and Brian Barker’s work The Symbols of Sovereignty (1979). The qualifier “national” is added to underline their link with the country as a whole. There are many symbols of sovereignty within a country, but they do not all have the same scope. The authority expressed by the mace of the House of Commons and that of the Senate does not extend outside Parliament, although the two chambers together enact laws with national and sometimes international implications. Issuing currency and stamps are signs of sovereignty, but not to the same degree as the national symbols described here, even if stamps are used both nationally and internationally. Using the expressions “national symbols” or “state symbols” without the qualifier “sovereign” does not seem complete. The beaver is a national or state symbol of Canada but serves more to express identity than sovereignty. The flag, coat of arms and great seal of a country translate into concrete applications such abstract notions as sovereignty, national independence, self-government and public authority.

The most authoritative work on the matter is Conrad Swan’s Canada: Symbols of Sovereignty in which he designates such symbols “as the expression of principles of constitutional as well as international law” (see his preface). Yet a seldom raised question is, Why Canada has three symbols instead of just one? The obvious answer is that they each serve a different purpose, but clarifying the nature of these different functions is complex. What follows is an attempt to explain in simple terms some of these distinctions. Because the subject retains many complexities, links are included to websites where the reader can find additional information. The essential points are also summarized in a section entitled “In a Nutshell” at the end of the analysis.

N. B.

All the websites quoted here were accessed on 4 April 2017.

All the websites quoted here were accessed on 4 April 2017.

The National Flag

More than any other symbol, the flag identifies the nation and the country. At the United Nations Headquarters in New York, Canada like other nations is represented by its flag. At international events like the Olympics, nations are again represented by their country’s flag. Canada’s national flag is flown at all federal government buildings, airports, as well as military bases and establishments within and outside Canada. Since 1965, the flag is the most visible mark of Canadian identity outside embassies. Five national flags fly on Parliament Hill: one over the Peace Tower, one on each side of the Centre Block, one over the West Block, and one over the East Block. A flag is present in the House of Commons and two in the Senate, one on each side of the thrones. The nation’s flag is displayed in the office of members of Parliament and usually in that of high ranking government officials. The rules for flying the national flag are mostly technical and are aimed at preserving the dignity and respect it is due, but are not particularly restrictive, see: http://canada.pch.gc.ca/eng/1444133232522.

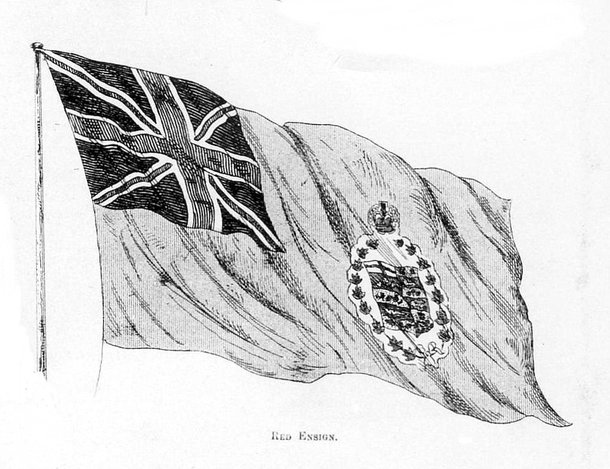

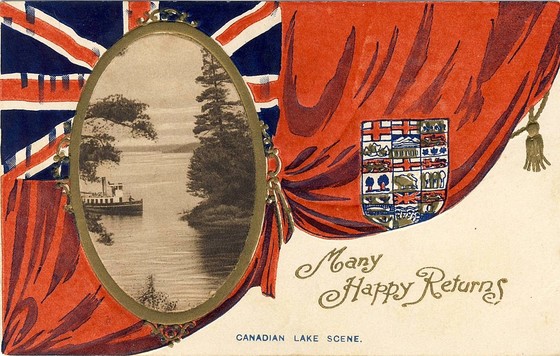

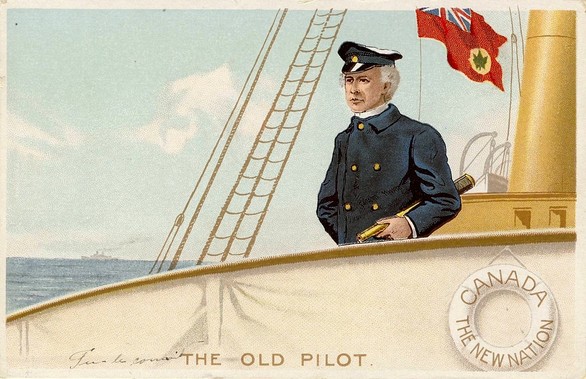

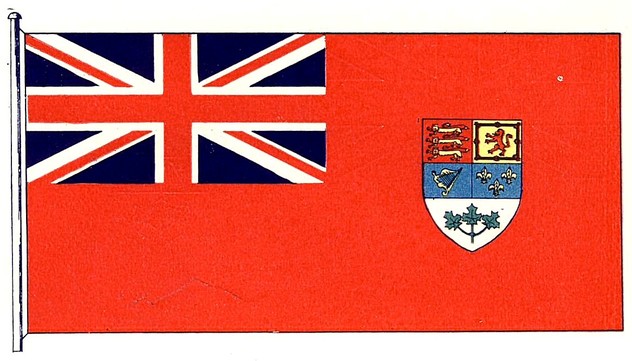

The one sure sign that the Canadian flag is considered the essential national emblem is the amount of public involvement that led to its choice. In 1866 as the terms of Confederation were being negotiated, a flag was proposed for the country by the architect Etienne-Eugène Taché, namely a beaver within a wreath of maple with the royal crown above (Robert Merrill Black, “Gleaned Here and there” in Heraldry in Canada, Dec. 1990, p. 24). Immediately after Confederation, Canadians adopted the Red Ensign as their distinctive flag with the Dominion shield of arms in the fly (figs. 1-2). This was done by popular consent, not by the government authority. Articles and pamphlets promoted their own choice for a national flag. This tendency intensified during Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King’s failed attempts to give Canada its own distinctive flag in 1925 and again in 1945. During Prime Minister Richard Bedford Bennett’s term (1930-35), a large number of flag proposals were sent to the government (See Christopher McCreery’s, “Bennett’s ‘NEW’ Canadian Flag” in Heraldry in Canada, part 1, Winter 2003 and part 2, Spring 2003). But the most intense period of public involvement occurred in the 1960’s when Lester Pearson raised the flag question again. Thousands of proposals were made by the public; many articles and pamphlets appeared; there were public demonstrations and heated debate in Parliament that the public followed in the media. In other words, the public was both concerned and involved.

A country’s flag is the symbol that arouses the most emotion. There can be a surge of national pride at a flag raising ceremony. When the flag is treated with disrespect, people get angry. In moments of strife, the national flag becomes the symbol of the ultimate sacrifice of giving one’s life for one’s country. The coffins of soldiers or members of the RCMP who have died in the service of their country are draped in the national flag as are those of journalists who were fatalities of war, for instance Michelle Lang, a Calgary Herald reporter and first Canadian journalist to die in the War in Afghanistan. Persons with a noted political or military career usually receive the same honour, for instance, Jeanne Sauvé, Lincoln Alexander, Jim Flaherty, Jack Layton and Ernest Alvia “Smokey” Smith, the only private soldier to earn the Victoria Cross in the Second World War. The casket of Peter Lougheed, former premier of Alberta, was adorned with both the national flag and the provincial flag. It is interesting that John Diefenbaker’s casket in 1979 was draped in both the Canadian Red Ensign which he defended and the present Canadian Flag which he opposed. There is no hard and fast rule on the matter, a family may choose to drape the coffin of a soldier or former soldier in the national flag no matter the rank or accomplishments (see the section “The Canadian Flag” at: http://www.rcmilord.com/media/Guidelines-for-Military-Funerals-in-Civilian-Parishes.pdf). In fact, there seems to be no rule to prevent any Canadian from using the flag in this way.

The flag is widely flown outside government circles. It is carried in parades and is present at many types of conventions and gatherings. It is seen in numerous public places such as town squares, shopping centres, at the entrance of parks. It is flown outside a large variety of buildings such as educational institutions, libraries, museums, planetariums, city halls, and fire stations. It is displayed as well outside some purely commercial buildings such as hotels, banks, stores, manufactures and large office buildings. In such cases, it is rarely flown alone. This is well illustrated by hotels that often fly the flags of a province, of Canada, and of a municipality. To these are sometimes added the flag of the United States, the Union Jack and the flag of the hotel or hotel chain which is frequently a logotype. Sometimes the flags of all the provinces accompany the national flag. By looking at a number store chains and enterprises that have buildings in many municipalities, I concluded that, apart from hotels, company buildings that display the national flag are not that numerous. Since it can be present or absent on buildings owned by the same firm and with the same name, it appears that the decision to fly the flag tends to be left to the manager of individual outlets. In the 50 years that I have been involved with heraldry, I have never seen Canada’s coat of arms displayed at the entrance of a commercial building. This would inevitably convey the impression that the building is a government one.

Tourist agencies will display the flag of many countries, for instance on tour buses for visitors. If the coats of arms of countries were ever used in this way, it would be a rare exception because flags, not coats of arms, are seen as the quintessential emblems of nations. Moreover, many tourists would not recognize the generally lesser known armorial devices.

Besides representing people collectively, national flags have a strong connection with individuals who sometimes fly them in their yards, stick them on their luggage when travelling and even paint them on their faces at sportive events. On Canada Day, a number of apartment dwellers hang the national flag from their balconies. Students are known to pin the flag to the wall of their dormitory. Small flags are ideal to be placed on a shelf in one’s apartment or on an office desk; to be carried in hand on festive days, or otherwise displayed on one’s person such as inserted in a pocket or hat band. The fact that the national flag is flown in public places and by individuals to show patriotism clearly indicates that the flag is viewed as the emblem of all collectively and of everyone individually.

The flag appears in many forms such as in print, on postage stamps and on a large number of souvenirs. It has been replicated in stained glass and in enamelled designs. But there is something special about a flag flowing in the wind from a flagpole where it can be seen at a distance. A flag fluttering in the wind looks alive; it is subject to many contortions and seems to display many moods. Yet the flag remains the most stable identifier of a nation and is rarely changed except following a momentous event such a sweeping revolution.

“The flag symbol is used to identify all departments, agencies, corporations, commissions, boards, councils, and other federal bodies and activities, unless they are authorized to be identified by the Coat of Arms.” (Federal identity Program Manual, 1.1: http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/hgw-cgf/oversight-surveillance/communications/fip-pcim/man/mantb-eng.asp). This statement clearly tells us that the flag and coat of arms of Canada share the task of identifying the services of government. This is a relatively new development since the national flag was adopted in 1965 only. The flag is of a simpler, more modern and friendlier looking design than the coat of arms. It has only one symbol, the single maple leaf, for all Canadians. This seems to go a long way towards explaining its adoption to identify many sectors of the Canadian Government, see also http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/hgw-cgf/oversight-surveillance/communications/fip-pcim/index-eng.asp. The national flag is explicitly protected from unauthorized commercial use by section 9(1)(e) of the Trade-Marks Act (http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/T-13/page-2.html#h-3).

Further reading: “National Flag of Canada” in The Canadian Encyclopedia: http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/flag-of-canada/; Alistair B. Fraser, The Flag of Canada: http://fraser.cc/FlagsCan/; John Ross Matheson, Canada’s Flag: a Search for a Country (Belleville [Ontario]: Mika Publishing, 1986).

More than any other symbol, the flag identifies the nation and the country. At the United Nations Headquarters in New York, Canada like other nations is represented by its flag. At international events like the Olympics, nations are again represented by their country’s flag. Canada’s national flag is flown at all federal government buildings, airports, as well as military bases and establishments within and outside Canada. Since 1965, the flag is the most visible mark of Canadian identity outside embassies. Five national flags fly on Parliament Hill: one over the Peace Tower, one on each side of the Centre Block, one over the West Block, and one over the East Block. A flag is present in the House of Commons and two in the Senate, one on each side of the thrones. The nation’s flag is displayed in the office of members of Parliament and usually in that of high ranking government officials. The rules for flying the national flag are mostly technical and are aimed at preserving the dignity and respect it is due, but are not particularly restrictive, see: http://canada.pch.gc.ca/eng/1444133232522.

The one sure sign that the Canadian flag is considered the essential national emblem is the amount of public involvement that led to its choice. In 1866 as the terms of Confederation were being negotiated, a flag was proposed for the country by the architect Etienne-Eugène Taché, namely a beaver within a wreath of maple with the royal crown above (Robert Merrill Black, “Gleaned Here and there” in Heraldry in Canada, Dec. 1990, p. 24). Immediately after Confederation, Canadians adopted the Red Ensign as their distinctive flag with the Dominion shield of arms in the fly (figs. 1-2). This was done by popular consent, not by the government authority. Articles and pamphlets promoted their own choice for a national flag. This tendency intensified during Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King’s failed attempts to give Canada its own distinctive flag in 1925 and again in 1945. During Prime Minister Richard Bedford Bennett’s term (1930-35), a large number of flag proposals were sent to the government (See Christopher McCreery’s, “Bennett’s ‘NEW’ Canadian Flag” in Heraldry in Canada, part 1, Winter 2003 and part 2, Spring 2003). But the most intense period of public involvement occurred in the 1960’s when Lester Pearson raised the flag question again. Thousands of proposals were made by the public; many articles and pamphlets appeared; there were public demonstrations and heated debate in Parliament that the public followed in the media. In other words, the public was both concerned and involved.

A country’s flag is the symbol that arouses the most emotion. There can be a surge of national pride at a flag raising ceremony. When the flag is treated with disrespect, people get angry. In moments of strife, the national flag becomes the symbol of the ultimate sacrifice of giving one’s life for one’s country. The coffins of soldiers or members of the RCMP who have died in the service of their country are draped in the national flag as are those of journalists who were fatalities of war, for instance Michelle Lang, a Calgary Herald reporter and first Canadian journalist to die in the War in Afghanistan. Persons with a noted political or military career usually receive the same honour, for instance, Jeanne Sauvé, Lincoln Alexander, Jim Flaherty, Jack Layton and Ernest Alvia “Smokey” Smith, the only private soldier to earn the Victoria Cross in the Second World War. The casket of Peter Lougheed, former premier of Alberta, was adorned with both the national flag and the provincial flag. It is interesting that John Diefenbaker’s casket in 1979 was draped in both the Canadian Red Ensign which he defended and the present Canadian Flag which he opposed. There is no hard and fast rule on the matter, a family may choose to drape the coffin of a soldier or former soldier in the national flag no matter the rank or accomplishments (see the section “The Canadian Flag” at: http://www.rcmilord.com/media/Guidelines-for-Military-Funerals-in-Civilian-Parishes.pdf). In fact, there seems to be no rule to prevent any Canadian from using the flag in this way.

The flag is widely flown outside government circles. It is carried in parades and is present at many types of conventions and gatherings. It is seen in numerous public places such as town squares, shopping centres, at the entrance of parks. It is flown outside a large variety of buildings such as educational institutions, libraries, museums, planetariums, city halls, and fire stations. It is displayed as well outside some purely commercial buildings such as hotels, banks, stores, manufactures and large office buildings. In such cases, it is rarely flown alone. This is well illustrated by hotels that often fly the flags of a province, of Canada, and of a municipality. To these are sometimes added the flag of the United States, the Union Jack and the flag of the hotel or hotel chain which is frequently a logotype. Sometimes the flags of all the provinces accompany the national flag. By looking at a number store chains and enterprises that have buildings in many municipalities, I concluded that, apart from hotels, company buildings that display the national flag are not that numerous. Since it can be present or absent on buildings owned by the same firm and with the same name, it appears that the decision to fly the flag tends to be left to the manager of individual outlets. In the 50 years that I have been involved with heraldry, I have never seen Canada’s coat of arms displayed at the entrance of a commercial building. This would inevitably convey the impression that the building is a government one.

Tourist agencies will display the flag of many countries, for instance on tour buses for visitors. If the coats of arms of countries were ever used in this way, it would be a rare exception because flags, not coats of arms, are seen as the quintessential emblems of nations. Moreover, many tourists would not recognize the generally lesser known armorial devices.

Besides representing people collectively, national flags have a strong connection with individuals who sometimes fly them in their yards, stick them on their luggage when travelling and even paint them on their faces at sportive events. On Canada Day, a number of apartment dwellers hang the national flag from their balconies. Students are known to pin the flag to the wall of their dormitory. Small flags are ideal to be placed on a shelf in one’s apartment or on an office desk; to be carried in hand on festive days, or otherwise displayed on one’s person such as inserted in a pocket or hat band. The fact that the national flag is flown in public places and by individuals to show patriotism clearly indicates that the flag is viewed as the emblem of all collectively and of everyone individually.

The flag appears in many forms such as in print, on postage stamps and on a large number of souvenirs. It has been replicated in stained glass and in enamelled designs. But there is something special about a flag flowing in the wind from a flagpole where it can be seen at a distance. A flag fluttering in the wind looks alive; it is subject to many contortions and seems to display many moods. Yet the flag remains the most stable identifier of a nation and is rarely changed except following a momentous event such a sweeping revolution.

“The flag symbol is used to identify all departments, agencies, corporations, commissions, boards, councils, and other federal bodies and activities, unless they are authorized to be identified by the Coat of Arms.” (Federal identity Program Manual, 1.1: http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/hgw-cgf/oversight-surveillance/communications/fip-pcim/man/mantb-eng.asp). This statement clearly tells us that the flag and coat of arms of Canada share the task of identifying the services of government. This is a relatively new development since the national flag was adopted in 1965 only. The flag is of a simpler, more modern and friendlier looking design than the coat of arms. It has only one symbol, the single maple leaf, for all Canadians. This seems to go a long way towards explaining its adoption to identify many sectors of the Canadian Government, see also http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/hgw-cgf/oversight-surveillance/communications/fip-pcim/index-eng.asp. The national flag is explicitly protected from unauthorized commercial use by section 9(1)(e) of the Trade-Marks Act (http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/T-13/page-2.html#h-3).

Further reading: “National Flag of Canada” in The Canadian Encyclopedia: http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/flag-of-canada/; Alistair B. Fraser, The Flag of Canada: http://fraser.cc/FlagsCan/; John Ross Matheson, Canada’s Flag: a Search for a Country (Belleville [Ontario]: Mika Publishing, 1986).

Fig. 1 Red Ensign in the Canadian Illustrated News, 6 May 1871, p. 281. Page 274 reads: “The Red Ensign, or flag of the Dominion proper, is for general use, and resembles the Blue Ensign in detail, the colour of the field alone being different.” The Canadian Blue Ensign with only the four-province shield in the fly was approved for government vessels in 1870. The Canadian Red Ensign with the same shield was approved for merchant ships in 1892. Its use on land as the flag of the Dominion of Canada after Confederation was a popular initiative without official sanction.

Fig. 2. After 1907, the Red Ensign used as Canada’s national flag sometimes featured a nine-province shield as shown here. This busy design was difficult to recognize when flying in the wind at a distance. Postcard by “B.B. London. [Birn Bros.] Manufactured in England.” From the postcard collection of Auguste and Paula Vachon.

Fig. 3. In 1896 Edward Marion Chadwick proposed that the composite Dominion shield in the fly of the Red Ensign be replaced by something simpler, either a single maple leaf or three leaves on one stem in centre of a white disc. He favoured three leaves. The idea of the single leaf was being circulated at the time but was not his own (E.M. Chadwick, "The Canadian Flag" Canadian Almanac [Toronto: Copp Clark, 1896], pp. 228, 233). The Numismatic Society of Montreal proposed a Union Jack with a gold leaf in centre as the national flag and a Red Ensign with a gold leaf in the fly as the merchant ensign ( Herbert George Todd, Armory and Lineages of Canada, 1919, plate I and captions, following p. 122) When a joint committee of the Senate and House of Commons appointed by the Liberal government of Mackenzie King proposed a Red Ensign with a gold maple leaf in the fly in 1946, it was hardly a new design (J.R. Matheson, Canada’s Flag, 1986, p. 63). This postcard, which is dated 20 October 1908 by the sender, six days prior to the federal election of the 26, illustrates the endorsement of the one-leaf Red Ensign by Laurier and the Liberals. Private postcard printed by the Toronto Lithographic Company. From the postcard collection of Auguste and Paula Vachon.

Fig. 4. An order in council in 1922 authorized the Red Ensign with the arms granted to Canada in 1921 to be the new ensign of Canada’s Merchant Marine. In 1924 another order-in-council authorized its use on all Canadian buildings outside Canada. A further order in council in 1945 authorized the same version to fly from federal buildings within Canada and abroad as an interim measure until Canada would adopt a national flag officially. Many Canadians believed that the Red Ensign was the national flag of Canada and that changing it was violating history and tradition.

Fig. 5. Canada’s flag was a favourite symbol of sovereignty on souvenirs during the celebration of the hundredth anniversary of Confederation. Plate by New Chelsea China Co. Ltd., England. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

The Coat of Arms

The coat of arms (achievement of arms, armorial bearings, or simply arms) of Canada was granted to the country, namely the Dominion of Canada, by royal proclamation of George V on 21 November 1921. Surprisingly the instances where the arms are displayed as the emblem of the country rather than that of government are not numerous. It is the case on the old Canadian Red Ensign, on the old flag of the governor general, and more extensively on souvenirs such as ceramics, postcards, key chains, blazer patches, T-shirts. In many cases, both the notions of country and of government are present. If one sees the arms of a country on an embassy, the first impression is rightly that it represents that country, but the embassy is essentially an extension of a government in another country and the employees within the building are doing government work. Similarly the Canadian achievement of arms on the front cover of a passport with the word “CANADA” represents the country. It immediately reveals to immigration officers what country the traveller is from. But a closer look in the inside cover reveals another depiction of the coat of arms with a statement from the “Minister of Foreign Affairs of Canada” attesting to the authenticity of the passport. At the bottom, an inscription affirms that the passport is the property of the Government of Canada. On the inside back cover is seen the flag with the words “Government of Canada” and, at the bottom, a wordmark with the flag over the “a” in the word “Canada.” The same duality exists when Canada’s armorial bearings appear on coins, banknotes, and postage stamps. At first glance, they represent the country, but these instruments are issued by crown corporations, namely the Bank of Canada and Post Canada which are ultimately responsible to the government. Beyond these examples, the fact remains that the arms of Canada have mostly served to represent the federal government and are generally viewed as a symbol of the government.

Before the adoption of the Canadian flag, the coat of arms reigned supreme as the symbol of public authority of the federal government, but as we have seen, it now competes with the flag of Canada in that sphere. The Federal Identity Program describes its use as follows: “The arms of Canada is Her Majesty's Arms in Right of Canada. It is the identifying symbol of Parliament, the Federal Judiciary, Cabinet ministers, Commissions established under the Inquiries Act and countless quasi-judicial public service institutions. The arms of Canada represents the country's diplomatic presence around the world and is used on international treaties, Canadian passports and currency.” (http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/hgw-cgf/oversight-surveillance/communications/fip-pcim/index-eng.asp#toc3). A complementary statement reads: “The Coat of Arms is used to identify ministers and their offices, parliamentary secretaries, institutions whose heads report directly to Parliament, as well as institutions with quasi-judicial functions.” (Federal identity Program Manual, 1.1: https://www.canada.ca/en/treasury-board-secretariat/services/government-communications/federal-identity-program/manual.html#toc11-2)

The arms of Canada also represent the Office of the Prime Minister, the Office of the Leader of the Opposition, and are displayed on the letterhead of the House of Commons. A few members of Parliament, although not ministers, display them on their letterhead, website, and sometimes on the front of their constituency office. David McGuinty, Member of Parliament for Ottawa South, displays the arms of Canada in all three places. I have seen many times the coat of arms on the sign in front of his office on Bank St., Ottawa. His letterhead can be seen here: http://www.unempgeninfo.com/canada/unempqs/mcguintylett.pdf and his site can be consulted at: http://dmcguinty.liberal.ca/. Badges which include Canada’s shield of arms on maces were confirmed by the Canadian Heraldic Authority for the House of Commons, the Senate, and the Parliament of Canada (see: http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1246&ProjectImageID=1613 — http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1283&ShowAll=1 — http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1284&ProjectElementID=4487).

The offices of agents of Parliament that display the coat of arms as identifier are: the Auditor General, the Commissioner of Official Languages, the Privacy Commissioner, the Information Commissioner, the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner, the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner, and the Commissioner of Lobbying. On the internet at least, Elections Canada headed by the Chief Electoral Officer apparently uses mostly a logo: http://www.elections.ca/. The armorial bearings of Canada identify certain ranks in the Canadian armed forces, see: http://www.forces.gc.ca/assets/FORCES_Internet/docs/en/honours-history-badges-colours-flags/insignia-poster.pdf and http://www.forces.gc.ca/en/honours-history-badges-insignia/rank.page.

The royal arms are traditionally associated with the administration of justice. The Supreme Court of Canada is still identified by the Royal Arms of Canada (fig. 8), but the Federal Court was granted its own armorial bearings, flag and badge by the Chief Herald of Canada in 2007 (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1203&ShowAll=1). The Court Martial Appeal Court of Canada was likewise granted arms in 1993 (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1684&ShowAll=1). Many of the federal Administrative Tribunals (agencies that implement legislative policy) are identified by the flag with the words “Government of Canada,” usually also with a large red stylized maple leaf as on the flag, and sometimes the Canada wordmark. There seems to be a tendency to abandon the arms of Canada in favour of this combination. For instance, the Public Service Staffing Tribunal and Public Service Labour Relations Board were formerly both identified by the royal arms of Canada. When they merged into the Public Service Labour Relations and Employment Board in 2014, the new organization adopted the flag and maple leaf formula. The National Parole Board was granted arms and a badge by the Chief Herald of Canada in 2014 (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=2548&ProjectElementID=9002). The Canadian Human Rights Commission and the Specific Claims Tribunal Canada have both adopted a logo. Logos are generally not favoured by heraldists, but they still make their way into government circles. Most crown corporations such Canada Post, Air Canada, Via Rail, Canadian Museum of History, National Capital Commission, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and others all have a logo.

Some administrative Tribunals that have so far (January 2017) retained the royal arms of Canada as their identifying mark are: Military Grievances External Review Committee, Immigration and Refugee Board, Privacy Commissioner of Canada, Public Service Staff Relations Board, Competition Tribunal, Public Servants Disclosure Protection Tribunal, Social Security Tribunal, and Transportation Appeal Tribunal of Canada.

Canada’s achievement of arms appears on the Great Seal of Canada since King George VI and on the interim seal of the governor general. It is seen along with the flag on the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedom; it adorns the commemorative plaques of the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada. The coat of arms is also present on certificates of “Commemoration of Canadian Citizenship” and on “Certificates of Canadian Citizenship” (citizenship cards) where, before February 2012, it was printed on the back of the card along with the image of the Great Seal of Canada. On the front of the card, the national flag is accompanied by the inscription “Government of Canada” (see: http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/citizenship/documents.asp). Canada’s armorial bearings are still seen on some federal government buildings, including embassies and older post office buildings (fig. 7), and are reproduced on various monuments. The number of coat of arms gifts created specifically for Canadian embassies is remarkable: https://www.zazzle.ca/canadian+embassy+gifts and http://www.cowcow.com/shop/watches/canadian-embassy.

The coat of arms surely arouses a certain degree of national pride and a sense of identity since it appears on souvenirs which embody such notions. Nevertheless, the arms come across as a more formal symbol than the flag and, as already mentioned, remain mostly associated with the authority of government. The three maple leaves on the shield represent Canada, but the four arms in the base of the shield honour the founding nations: England, France, Scotland and Ireland. The arms are subject to change both in style and content. Stylistic changes were made in 1923 and 1957 to the coat of arms granted in 1921, and in 1994 the style was again changed and the motto of the Order of Canada added, giving four versions so far (http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/arms-of-canada.html). The royal crown at the apex denotes that Canada is a constitutional monarchy, which is a key aspect of the Canadian government. As stated in the quote above, the arms of Canada are those of Her Majesty in Right of Canada, or more simply put, the arms of Elizabeth II as Queen of Canada. They remain the royal arms of Canada for each succeeding sovereign.

Choosing Canada’s coat of arms was done by a committee of four government officials appointed by order-in-council dated 26 March 1919. There were a few suggestions and designs transmitted by letter or through the press to the committee, mostly by heraldic amateurs, but essentially the process was a government matter. The committee clashed with Garter King of Arms who refused to accept an emblem that took the form of royal arms, but the impasse was resolved by having the grant made by royal proclamation. When the motto of the Order of Canada was added around the shield in 1994, there were mostly negative comments in the press and some wrangling in the House of Commons, none of which had any significant effect.

The coat of arms can be represented in many mediums: printed flat on paper or cloth or other supports, in stained glass, engraved in metal or glass, in three dimensions as part sculptures, carvings or mouldings. It is represented both in colour and monochrome format.

Like the national flag, the coat of arms is explicitly protected from unauthorized commercial use by section 9(1)(e) of the Trade-Marks Act (http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/T-13/page-2.html#h-3).

Further reading: Auguste Vachon, Canada’s Coat of Arms: Defining a Country within an Empire: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/canadarsquos-coat-of-arms-defining-a-country-within-an-empire.html.

The coat of arms (achievement of arms, armorial bearings, or simply arms) of Canada was granted to the country, namely the Dominion of Canada, by royal proclamation of George V on 21 November 1921. Surprisingly the instances where the arms are displayed as the emblem of the country rather than that of government are not numerous. It is the case on the old Canadian Red Ensign, on the old flag of the governor general, and more extensively on souvenirs such as ceramics, postcards, key chains, blazer patches, T-shirts. In many cases, both the notions of country and of government are present. If one sees the arms of a country on an embassy, the first impression is rightly that it represents that country, but the embassy is essentially an extension of a government in another country and the employees within the building are doing government work. Similarly the Canadian achievement of arms on the front cover of a passport with the word “CANADA” represents the country. It immediately reveals to immigration officers what country the traveller is from. But a closer look in the inside cover reveals another depiction of the coat of arms with a statement from the “Minister of Foreign Affairs of Canada” attesting to the authenticity of the passport. At the bottom, an inscription affirms that the passport is the property of the Government of Canada. On the inside back cover is seen the flag with the words “Government of Canada” and, at the bottom, a wordmark with the flag over the “a” in the word “Canada.” The same duality exists when Canada’s armorial bearings appear on coins, banknotes, and postage stamps. At first glance, they represent the country, but these instruments are issued by crown corporations, namely the Bank of Canada and Post Canada which are ultimately responsible to the government. Beyond these examples, the fact remains that the arms of Canada have mostly served to represent the federal government and are generally viewed as a symbol of the government.

Before the adoption of the Canadian flag, the coat of arms reigned supreme as the symbol of public authority of the federal government, but as we have seen, it now competes with the flag of Canada in that sphere. The Federal Identity Program describes its use as follows: “The arms of Canada is Her Majesty's Arms in Right of Canada. It is the identifying symbol of Parliament, the Federal Judiciary, Cabinet ministers, Commissions established under the Inquiries Act and countless quasi-judicial public service institutions. The arms of Canada represents the country's diplomatic presence around the world and is used on international treaties, Canadian passports and currency.” (http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/hgw-cgf/oversight-surveillance/communications/fip-pcim/index-eng.asp#toc3). A complementary statement reads: “The Coat of Arms is used to identify ministers and their offices, parliamentary secretaries, institutions whose heads report directly to Parliament, as well as institutions with quasi-judicial functions.” (Federal identity Program Manual, 1.1: https://www.canada.ca/en/treasury-board-secretariat/services/government-communications/federal-identity-program/manual.html#toc11-2)

The arms of Canada also represent the Office of the Prime Minister, the Office of the Leader of the Opposition, and are displayed on the letterhead of the House of Commons. A few members of Parliament, although not ministers, display them on their letterhead, website, and sometimes on the front of their constituency office. David McGuinty, Member of Parliament for Ottawa South, displays the arms of Canada in all three places. I have seen many times the coat of arms on the sign in front of his office on Bank St., Ottawa. His letterhead can be seen here: http://www.unempgeninfo.com/canada/unempqs/mcguintylett.pdf and his site can be consulted at: http://dmcguinty.liberal.ca/. Badges which include Canada’s shield of arms on maces were confirmed by the Canadian Heraldic Authority for the House of Commons, the Senate, and the Parliament of Canada (see: http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1246&ProjectImageID=1613 — http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1283&ShowAll=1 — http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1284&ProjectElementID=4487).

The offices of agents of Parliament that display the coat of arms as identifier are: the Auditor General, the Commissioner of Official Languages, the Privacy Commissioner, the Information Commissioner, the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner, the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner, and the Commissioner of Lobbying. On the internet at least, Elections Canada headed by the Chief Electoral Officer apparently uses mostly a logo: http://www.elections.ca/. The armorial bearings of Canada identify certain ranks in the Canadian armed forces, see: http://www.forces.gc.ca/assets/FORCES_Internet/docs/en/honours-history-badges-colours-flags/insignia-poster.pdf and http://www.forces.gc.ca/en/honours-history-badges-insignia/rank.page.

The royal arms are traditionally associated with the administration of justice. The Supreme Court of Canada is still identified by the Royal Arms of Canada (fig. 8), but the Federal Court was granted its own armorial bearings, flag and badge by the Chief Herald of Canada in 2007 (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1203&ShowAll=1). The Court Martial Appeal Court of Canada was likewise granted arms in 1993 (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1684&ShowAll=1). Many of the federal Administrative Tribunals (agencies that implement legislative policy) are identified by the flag with the words “Government of Canada,” usually also with a large red stylized maple leaf as on the flag, and sometimes the Canada wordmark. There seems to be a tendency to abandon the arms of Canada in favour of this combination. For instance, the Public Service Staffing Tribunal and Public Service Labour Relations Board were formerly both identified by the royal arms of Canada. When they merged into the Public Service Labour Relations and Employment Board in 2014, the new organization adopted the flag and maple leaf formula. The National Parole Board was granted arms and a badge by the Chief Herald of Canada in 2014 (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=2548&ProjectElementID=9002). The Canadian Human Rights Commission and the Specific Claims Tribunal Canada have both adopted a logo. Logos are generally not favoured by heraldists, but they still make their way into government circles. Most crown corporations such Canada Post, Air Canada, Via Rail, Canadian Museum of History, National Capital Commission, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and others all have a logo.

Some administrative Tribunals that have so far (January 2017) retained the royal arms of Canada as their identifying mark are: Military Grievances External Review Committee, Immigration and Refugee Board, Privacy Commissioner of Canada, Public Service Staff Relations Board, Competition Tribunal, Public Servants Disclosure Protection Tribunal, Social Security Tribunal, and Transportation Appeal Tribunal of Canada.

Canada’s achievement of arms appears on the Great Seal of Canada since King George VI and on the interim seal of the governor general. It is seen along with the flag on the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedom; it adorns the commemorative plaques of the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada. The coat of arms is also present on certificates of “Commemoration of Canadian Citizenship” and on “Certificates of Canadian Citizenship” (citizenship cards) where, before February 2012, it was printed on the back of the card along with the image of the Great Seal of Canada. On the front of the card, the national flag is accompanied by the inscription “Government of Canada” (see: http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/citizenship/documents.asp). Canada’s armorial bearings are still seen on some federal government buildings, including embassies and older post office buildings (fig. 7), and are reproduced on various monuments. The number of coat of arms gifts created specifically for Canadian embassies is remarkable: https://www.zazzle.ca/canadian+embassy+gifts and http://www.cowcow.com/shop/watches/canadian-embassy.

The coat of arms surely arouses a certain degree of national pride and a sense of identity since it appears on souvenirs which embody such notions. Nevertheless, the arms come across as a more formal symbol than the flag and, as already mentioned, remain mostly associated with the authority of government. The three maple leaves on the shield represent Canada, but the four arms in the base of the shield honour the founding nations: England, France, Scotland and Ireland. The arms are subject to change both in style and content. Stylistic changes were made in 1923 and 1957 to the coat of arms granted in 1921, and in 1994 the style was again changed and the motto of the Order of Canada added, giving four versions so far (http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/arms-of-canada.html). The royal crown at the apex denotes that Canada is a constitutional monarchy, which is a key aspect of the Canadian government. As stated in the quote above, the arms of Canada are those of Her Majesty in Right of Canada, or more simply put, the arms of Elizabeth II as Queen of Canada. They remain the royal arms of Canada for each succeeding sovereign.

Choosing Canada’s coat of arms was done by a committee of four government officials appointed by order-in-council dated 26 March 1919. There were a few suggestions and designs transmitted by letter or through the press to the committee, mostly by heraldic amateurs, but essentially the process was a government matter. The committee clashed with Garter King of Arms who refused to accept an emblem that took the form of royal arms, but the impasse was resolved by having the grant made by royal proclamation. When the motto of the Order of Canada was added around the shield in 1994, there were mostly negative comments in the press and some wrangling in the House of Commons, none of which had any significant effect.

The coat of arms can be represented in many mediums: printed flat on paper or cloth or other supports, in stained glass, engraved in metal or glass, in three dimensions as part sculptures, carvings or mouldings. It is represented both in colour and monochrome format.

Like the national flag, the coat of arms is explicitly protected from unauthorized commercial use by section 9(1)(e) of the Trade-Marks Act (http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/T-13/page-2.html#h-3).

Further reading: Auguste Vachon, Canada’s Coat of Arms: Defining a Country within an Empire: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/canadarsquos-coat-of-arms-defining-a-country-within-an-empire.html.

Fig. 6. The coat of arms of Canada as granted in 1921 on a plate commemorating the 175th anniversary of the Albion Lodge of Quebec City. A.F. & A.M stands for Ancient Free and Accepted Masons. One author states: “Albion, No. 2, Quebec. The Warrant of this famous old Lodge is of date June 12, 1752” see John Hamilton Graham, Outlines of the History of Freemasonry in the Province of Quebec (Montreal: John Lovell & Son, 1892), p. 433. Page 431 of the same work states: “No. I, Montreal, — The original Warrant of this noted Lodge, No. 22.I.R., was of date March 4, 1752, one hundred and forty years ago ! … It was attached to the 46th Regt. of Foot, and named the Lodge of ‘Social and Military Virtues.’ ” On the same page, we learn that the Montreal warrant was issued by the Grand Lodge of Ireland. On page 37, the 46th Regiment of Foot is included in a list of regiments that were present at the capitulation of Montreal in 1760 and to which lodges were attached. The Seven Years War (1756-1763) which led to the capture of Quebec City in the Fall of 1759 started in North America in 1754. There is surely an explanation, but although I have speculated a great deal on the matter, I cannot fathom why Grand Lodges in Great-Britain would have issued warrants for two cities that were part of New France in 1752 and remained thus until the Treaty of Paris of 1763. Commemorative plate by Adams, England, 1927, from the Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

Fig. 7. Armorial bearings of Canada, on the corner of the Ottawa Central Post Office, Sparks and Elgin Streets, building completed in 1939.

Fig. 8. This sign on the lawn in front of the Supreme Court building confirms that this national institution is identified by the armorial bearings of Canada.

The Great Seal

The great seal, which arrived on the scene immediately after Confederation, is Canada’s oldest symbol of sovereignty, yet it remains the less known because documents with the impressed seal are not widely distributed. Prior to the Statute of Westminster (1931) which gave Canada full legal autonomy, the seal was described as “deputed.” Today with the queen on the throne, the inscription “Elizabeth II Queen of Canada” and the coat of arms of Her Majesty in Right of Canada below the throne, the design spells out clearly that Canada is a constitutional monarchy with its own sovereign (fig. 9). At first glance, it would seem to be the one symbol that unequivocally represents the country and, although it does that, it is also an instrument of government. The seal embodies the power and authority of the Crown flowing from the sovereign to the government. This is clearly exemplified by a special ceremony. When elections are called, the great seal is returned to the governor general, it’s ultimate custodian and, following election, its custody is transferred to the Minister of Innovation, Science, and Economic Development (the ministry can change) and eventually to the Registrar General for its actual application to documents.

The Great Seal of Canada is affixed to a number of official documents as described in Seals Act Public Officers Act: http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/C.R.C.,_c._1331/page-1.html#h-3. As can be expected, it is most widely used to appoint persons to offices that exercise executive powers emanating from the Crown. While the coat of arms of Canada was assigned by a royal proclamation issued in England; the flag of Canada was assigned by a royal proclamation issued in Canada and bearing the present Great Seal of Canada. The seal clearly indicates on what authority a document is issued and guarantees its authenticity. Because it is large and contains impressive imagery, it embodies as well the notions of importance and prestige. Seals are frequently used to ensure that content will be kept secret and not tampered with such as when a seal is applied to the envelope of a letter. This is not the case for the great seal since it is affixed to open documents such as letters patent and proclamations. On the other hand, the seal could not be replicated without very exceptional means and in this sense is a further guarantee of authenticity of content.

The Great Seal of Canada is changed every time a new sovereign ascends the throne. George VI had two seals. His first seal was inscribed “IND. IMP.” (Indiae Imperator) a designation which was removed from his second seal after India gained its independence in 1947. The great seal does not give rise to the same strong patriotic emotions as does the flag. Somewhat like the coat of arms, it can still be admired for its pictorial composition. The style of the great seal came to us essentially from British royal seals. When the arms of Canada replaced the arms of the United Kingdom on the seal of George VI and when the same arms and the inscription “Queen of Canada” appeared on the present seal (fig. 13), these adjustments were handled by the Canadian government with no public input.

The great seal has sometimes appeared in print such as on citizenship cards as we have seen. It was used in printed form to identify Treasury Board shortly after Confederation and a few years after the adoption of the Canadian flag (fig. 10). The first seal (fig. 9) is carved in stone in the Hall of Honour of Parliament (http://www.parl.gc.ca/About/House/collections/heritage_spaces/honour/sculpture/6396-e.htm). It was replicated on a few commemoratives (figs. 11-12).

The great seal is protected under the Security of Information Act, Section 5(2)(e), see: http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/O-5/FullText.html.

Further reading: Conrad Swan, Canada: Symbols of Sovereignty (University of Toronto Press, 1977); Consumer and Corporate Affairs Canada, The Great Seal of Canada (1988).

The great seal, which arrived on the scene immediately after Confederation, is Canada’s oldest symbol of sovereignty, yet it remains the less known because documents with the impressed seal are not widely distributed. Prior to the Statute of Westminster (1931) which gave Canada full legal autonomy, the seal was described as “deputed.” Today with the queen on the throne, the inscription “Elizabeth II Queen of Canada” and the coat of arms of Her Majesty in Right of Canada below the throne, the design spells out clearly that Canada is a constitutional monarchy with its own sovereign (fig. 9). At first glance, it would seem to be the one symbol that unequivocally represents the country and, although it does that, it is also an instrument of government. The seal embodies the power and authority of the Crown flowing from the sovereign to the government. This is clearly exemplified by a special ceremony. When elections are called, the great seal is returned to the governor general, it’s ultimate custodian and, following election, its custody is transferred to the Minister of Innovation, Science, and Economic Development (the ministry can change) and eventually to the Registrar General for its actual application to documents.

The Great Seal of Canada is affixed to a number of official documents as described in Seals Act Public Officers Act: http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/C.R.C.,_c._1331/page-1.html#h-3. As can be expected, it is most widely used to appoint persons to offices that exercise executive powers emanating from the Crown. While the coat of arms of Canada was assigned by a royal proclamation issued in England; the flag of Canada was assigned by a royal proclamation issued in Canada and bearing the present Great Seal of Canada. The seal clearly indicates on what authority a document is issued and guarantees its authenticity. Because it is large and contains impressive imagery, it embodies as well the notions of importance and prestige. Seals are frequently used to ensure that content will be kept secret and not tampered with such as when a seal is applied to the envelope of a letter. This is not the case for the great seal since it is affixed to open documents such as letters patent and proclamations. On the other hand, the seal could not be replicated without very exceptional means and in this sense is a further guarantee of authenticity of content.

The Great Seal of Canada is changed every time a new sovereign ascends the throne. George VI had two seals. His first seal was inscribed “IND. IMP.” (Indiae Imperator) a designation which was removed from his second seal after India gained its independence in 1947. The great seal does not give rise to the same strong patriotic emotions as does the flag. Somewhat like the coat of arms, it can still be admired for its pictorial composition. The style of the great seal came to us essentially from British royal seals. When the arms of Canada replaced the arms of the United Kingdom on the seal of George VI and when the same arms and the inscription “Queen of Canada” appeared on the present seal (fig. 13), these adjustments were handled by the Canadian government with no public input.

The great seal has sometimes appeared in print such as on citizenship cards as we have seen. It was used in printed form to identify Treasury Board shortly after Confederation and a few years after the adoption of the Canadian flag (fig. 10). The first seal (fig. 9) is carved in stone in the Hall of Honour of Parliament (http://www.parl.gc.ca/About/House/collections/heritage_spaces/honour/sculpture/6396-e.htm). It was replicated on a few commemoratives (figs. 11-12).

The great seal is protected under the Security of Information Act, Section 5(2)(e), see: http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/O-5/FullText.html.

Further reading: Conrad Swan, Canada: Symbols of Sovereignty (University of Toronto Press, 1977); Consumer and Corporate Affairs Canada, The Great Seal of Canada (1988).

Fig. 9. The first Great Seal of Canada, Queen Victoria, photo of intaglio silver matrix. The photo was flipped to create a positive image for easier reading and to show what the impressed seal looks like. Library and Archives Canada, photo C 6792.

Fig. 10. A simplified version of Queen Victoria’s Great Seal served to identify Treasury Board of Canada for about a century from the 1870’s. Treasury Board was established in 1867 by Sir John A. Macdonald, but the first great seal was not used before 1870 when it arrived in Canada.

Fig. 11. The Great Seal of Canada used as the identifying mark of Treasury Board, on a glass mug made in England for its centennial in 1967. Property of Auguste and Paula Vachon.

Fig. 12. First Great Seal of Canada reproduced on a souvenir pin dish by Royal Doulton in 1967 for Canada’s Centennial. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

Fig. 13. Great Seal of Canada, Queen Elizabeth II. Silicone rubber mould in Library and Archives Canada, photo C 33866.

In a Nutshell

1. The National Flag

The flag is the emblem that more than any other symbolizes the nation and with which people identify as part of the nation. The flag has the potential to arouse strong emotions and is viewed as the symbol of sacrifice even to the point of giving one’s life for one’s country. Choosing a national flag can give rise to pronounced public fervour, but once adopted is a very stable instrument that is not changed except following momentous events like a revolution. The flag is widely flown outside government circles such as in parades, town squares and shopping centres. It is often depicted in print, but it is most effective when it flies in the wind taking on many shapes as if it were alive. The flag of Canada is a simple and modern looking design which has been widely enlisted to represent a modern government.

2. The Coat of Arms

The armorial achievement of Canada was designed by a committee of government officials and is generally viewed as representing government authority. It is a more formal, more complex, and more archaic looking than the flag and arouses more respect than patriotic sentiments. The flag has replaced the coat of arms to identify government departments. It is retained to represent the Houses of Parliament, the Office of the Prime Minister, the Office of the Leader of the Opposition, the offices of cabinet ministers, parliamentary secretaries and agents of Parliament. It represents the country on the cover of passports, outside embassies, on the great seals, on currency and stamps, although in all these cases there is strong government connection. On armorial souvenirs, it represents the country, generally without any government connection. It has undergone several changes in style over the years and one in style and content in 1994. Of the three symbols of sovereignty, it is the most vulnerable to being replaced by logos in areas that have a large public outreach.

3. The Great Seal

The great seal is the one instrument that clearly identifies Canada as a constitutional monarchy whose executive powers flow from the Crown. For this reason, it is most widely used to appoint holders of offices exercising executive powers. It is an impressive and very formal instrument which confers authenticity, authority and prestige to the documents to which it is affixed. It was used for many years as the identifying mark of Treasury Board. We see it carved in stone in the Parliament Building, and it has appeared a few times in print and on few souvenirs.

Concluding Remarks

National flags, armorial bearings and great seals are recognized as national symbols of sovereignty, but this abstract notion does not provide insight into the reasons why most nations have three such symbols instead of just one. Sovereignty is synonymous with self-government and governments exercise public authority. National flags, armorial bearings and great seals tell us from where this authority emanates and how it is exercised in specific spheres. In some countries like Peru the armorial device of the state is seen on its flag as well as on its great seal, but the three instruments remain distinct in their applications. One clear indication that the three emblems are essentially different in nature is that, while true armorial bearings follow heraldic rules, the imagery on both seals and flags can be devoid of any heraldic content or structure. The Great Seal of France has no heraldic content; the present flag of the City Ottawa is a modern graphic design which does not fit with conventional heraldry.

The decision to identify government departments with the flag was naturally a government decision, but the coat of arms could just as well have been retained for this purpose. The royal arms still identify most government departments in the United Kingdom, see: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations. Other applications could be decided by the Canadian government in years to come. Heraldic rules are not very helpful in deciding what use should be made of emblems after they become official because these rules mostly concern design. Because flags, armorial bearings and seals have been in use for centuries, those who delve in heraldry are generally aware of their traditional applications. While the past cannot completely dictate modern trends, it can provide useful insight. Now that a Canadian Heraldic Authority exists, it seems reasonable that its heralds should be consulted on the utilization of national symbols when such questions arise.

What I have written is my point of view as a historian and heraldist. While it reveals aspects that are specific to one or the other of the three national symbols of sovereignty of Canada, there can be no doubt that a legal expert or a specialist in constitutional history would justify their use very differently. This would undoubtedly shed new light on the nature of the tree emblems. A lot of the analysis here could apply to Canadian provinces and other countries that also have three symbols of sovereignty. Yet every jurisdiction has to be looked at separately because important differences exist as to how these symbols are viewed and used. Even when governments attempt to regulate the use of symbols, their applications tend to evolve in much the same way that languages do.

1. The National Flag

The flag is the emblem that more than any other symbolizes the nation and with which people identify as part of the nation. The flag has the potential to arouse strong emotions and is viewed as the symbol of sacrifice even to the point of giving one’s life for one’s country. Choosing a national flag can give rise to pronounced public fervour, but once adopted is a very stable instrument that is not changed except following momentous events like a revolution. The flag is widely flown outside government circles such as in parades, town squares and shopping centres. It is often depicted in print, but it is most effective when it flies in the wind taking on many shapes as if it were alive. The flag of Canada is a simple and modern looking design which has been widely enlisted to represent a modern government.

2. The Coat of Arms

The armorial achievement of Canada was designed by a committee of government officials and is generally viewed as representing government authority. It is a more formal, more complex, and more archaic looking than the flag and arouses more respect than patriotic sentiments. The flag has replaced the coat of arms to identify government departments. It is retained to represent the Houses of Parliament, the Office of the Prime Minister, the Office of the Leader of the Opposition, the offices of cabinet ministers, parliamentary secretaries and agents of Parliament. It represents the country on the cover of passports, outside embassies, on the great seals, on currency and stamps, although in all these cases there is strong government connection. On armorial souvenirs, it represents the country, generally without any government connection. It has undergone several changes in style over the years and one in style and content in 1994. Of the three symbols of sovereignty, it is the most vulnerable to being replaced by logos in areas that have a large public outreach.

3. The Great Seal

The great seal is the one instrument that clearly identifies Canada as a constitutional monarchy whose executive powers flow from the Crown. For this reason, it is most widely used to appoint holders of offices exercising executive powers. It is an impressive and very formal instrument which confers authenticity, authority and prestige to the documents to which it is affixed. It was used for many years as the identifying mark of Treasury Board. We see it carved in stone in the Parliament Building, and it has appeared a few times in print and on few souvenirs.

Concluding Remarks

National flags, armorial bearings and great seals are recognized as national symbols of sovereignty, but this abstract notion does not provide insight into the reasons why most nations have three such symbols instead of just one. Sovereignty is synonymous with self-government and governments exercise public authority. National flags, armorial bearings and great seals tell us from where this authority emanates and how it is exercised in specific spheres. In some countries like Peru the armorial device of the state is seen on its flag as well as on its great seal, but the three instruments remain distinct in their applications. One clear indication that the three emblems are essentially different in nature is that, while true armorial bearings follow heraldic rules, the imagery on both seals and flags can be devoid of any heraldic content or structure. The Great Seal of France has no heraldic content; the present flag of the City Ottawa is a modern graphic design which does not fit with conventional heraldry.

The decision to identify government departments with the flag was naturally a government decision, but the coat of arms could just as well have been retained for this purpose. The royal arms still identify most government departments in the United Kingdom, see: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations. Other applications could be decided by the Canadian government in years to come. Heraldic rules are not very helpful in deciding what use should be made of emblems after they become official because these rules mostly concern design. Because flags, armorial bearings and seals have been in use for centuries, those who delve in heraldry are generally aware of their traditional applications. While the past cannot completely dictate modern trends, it can provide useful insight. Now that a Canadian Heraldic Authority exists, it seems reasonable that its heralds should be consulted on the utilization of national symbols when such questions arise.

What I have written is my point of view as a historian and heraldist. While it reveals aspects that are specific to one or the other of the three national symbols of sovereignty of Canada, there can be no doubt that a legal expert or a specialist in constitutional history would justify their use very differently. This would undoubtedly shed new light on the nature of the tree emblems. A lot of the analysis here could apply to Canadian provinces and other countries that also have three symbols of sovereignty. Yet every jurisdiction has to be looked at separately because important differences exist as to how these symbols are viewed and used. Even when governments attempt to regulate the use of symbols, their applications tend to evolve in much the same way that languages do.