Managing a Heraldic Conflict / Gestion d’un conflit héraldique

Managing a Heraldic Conflict

The Jan.-Feb. 1990 issue of The Archivist was devoted to historical Canadian flags and especially to the flag of Canada. Dr. William Kaye Lamb, retired National Librarian and Archivist, had greatly enjoyed reading it and shared an experience of his own in a letter dated 19 February 1990 to Jean-Pierre Wallot, National Archivist of Canada.

“The Canadian flag issue of The Archivist is most interesting. I lived through the later years of the great flag debate, and I knew John Matheson quite well. There is an amusing story about the flag and the Royal Society that is probably not widely known. While the flag discussions were in progress, the Royal Society decided to secure a heraldically correct coat of arms, and the design we decided upon, which Alan Beddoe put in proper form for us, included a cluster of three maple leaves―a symbol that the Royal Society had used before. As the Society had a Royal charter, we decided that we had better get the approval of the Under Secretary of State, who vetoed the design because the Canadian flag was to have a three-leaf cluster, and we should substitute a single maple leaf. We did so―and then the flag design was changed to a single-leaf design, so we ended up in conflict after all!”

The “Pearson Pennant” (fig.1) with three leaves came up for debate in the House on 15 June 1964. The veto of the under secretary of state expresses his conviction that Pearson’s three-leaf pennant was about to be adopted. But vote of the flag committee, on 22 October 1964, eliminated the pennant in favour of a one-leaf flag.

Was the objection to the three leaves justifiable? Perhaps not, since there were precedents for the use of three red maple leaves and not just in the arms of Canada. From 1871, a sprig of three maple leaves proper, therefore potentially red, was held by a lion in the crest granted to Sir John Young, Baron Lisgar, second governor general of Canada. The Canadian Army badge with a sprig of three red maple leaves was adopted in 1940, and the badge of the Royal Canadian Legion, displaying a single red leaf, also preceded the Canadian national flag. Having one element of the country’s flag in the arms of a national society, such as the Royal Society of Canada, is clearly acceptable since this happens in many granted emblems, even when there is no government tie or national scope. Following the proclamation of the one-leaf flag in 1965, the Royal Heraldry Society of Canada was granted a shield on which an escutcheon featured a single red maple leaf on a white field (fig.2). A search through the Public Register of Arms, Flags and Badges of Canada, created in 1988, reveals the presence of a single red maple leaf on a white background in the emblems of a number of organizations and individuals, for example: the badge of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service and the badge and some of the flags of the Canadian Coast Guard. This is also seen in arms granted to the School of Public Service, the Friends of Austria, the Association des Levasseur d’Amérique, and in the personal arms of Andrew Austin Duncanson and John Gerald Patrick Langton.

The duplication of the maple leaf in the crest of the Royal Society of Canada and in the flag of Canada pales in comparison to the inclusion of the entire Royal Union Flag (Union Jack) in some granted Canadian coats of arms. The shield of the Royal Military College of Canada displays in centre the Union Jack on an escutcheon (also called Union badge or Union device) without any mark of difference (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1287&ShowAll=1). The shield of the City of Fredericton (New Brunswick) contains an escutcheon of the Union Jack and another of the Royal Arms of England, both topped by the royal crown (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1592&ShowAll=1). The top portion (the chief) of the shield of British Columbia features the Union devise differenced only with a small crown. The old badge of the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire (IODE) had a Union Jack escutcheon in centre which, interestingly, has since been replaced by a red maple leaf (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=2664&ShowAll=1).

One important role of heraldry is to mark allegiances. The arms of the Nova Scotia represent an excellent example of this. The shield replicates the flag of Scotland with the tinctures reversed while the escutcheon in centre shows the arms of Scotland intact. In light of this and the several unmodified replications of the United Kingdom’s flag as well as the use of a sprig of three red leave in Canadian emblems prior to 1965, it seems that the under secretary of state could have allowed the sprig of three maple leaves in the crest of the Royal Society of Canada. Clearly his apprehensions were not based on heraldic usage, but rather on the type of nitpicking often seen among persons in authority who have a fleeting encounter with heraldry.

The Jan.-Feb. 1990 issue of The Archivist was devoted to historical Canadian flags and especially to the flag of Canada. Dr. William Kaye Lamb, retired National Librarian and Archivist, had greatly enjoyed reading it and shared an experience of his own in a letter dated 19 February 1990 to Jean-Pierre Wallot, National Archivist of Canada.

“The Canadian flag issue of The Archivist is most interesting. I lived through the later years of the great flag debate, and I knew John Matheson quite well. There is an amusing story about the flag and the Royal Society that is probably not widely known. While the flag discussions were in progress, the Royal Society decided to secure a heraldically correct coat of arms, and the design we decided upon, which Alan Beddoe put in proper form for us, included a cluster of three maple leaves―a symbol that the Royal Society had used before. As the Society had a Royal charter, we decided that we had better get the approval of the Under Secretary of State, who vetoed the design because the Canadian flag was to have a three-leaf cluster, and we should substitute a single maple leaf. We did so―and then the flag design was changed to a single-leaf design, so we ended up in conflict after all!”

The “Pearson Pennant” (fig.1) with three leaves came up for debate in the House on 15 June 1964. The veto of the under secretary of state expresses his conviction that Pearson’s three-leaf pennant was about to be adopted. But vote of the flag committee, on 22 October 1964, eliminated the pennant in favour of a one-leaf flag.

Was the objection to the three leaves justifiable? Perhaps not, since there were precedents for the use of three red maple leaves and not just in the arms of Canada. From 1871, a sprig of three maple leaves proper, therefore potentially red, was held by a lion in the crest granted to Sir John Young, Baron Lisgar, second governor general of Canada. The Canadian Army badge with a sprig of three red maple leaves was adopted in 1940, and the badge of the Royal Canadian Legion, displaying a single red leaf, also preceded the Canadian national flag. Having one element of the country’s flag in the arms of a national society, such as the Royal Society of Canada, is clearly acceptable since this happens in many granted emblems, even when there is no government tie or national scope. Following the proclamation of the one-leaf flag in 1965, the Royal Heraldry Society of Canada was granted a shield on which an escutcheon featured a single red maple leaf on a white field (fig.2). A search through the Public Register of Arms, Flags and Badges of Canada, created in 1988, reveals the presence of a single red maple leaf on a white background in the emblems of a number of organizations and individuals, for example: the badge of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service and the badge and some of the flags of the Canadian Coast Guard. This is also seen in arms granted to the School of Public Service, the Friends of Austria, the Association des Levasseur d’Amérique, and in the personal arms of Andrew Austin Duncanson and John Gerald Patrick Langton.

The duplication of the maple leaf in the crest of the Royal Society of Canada and in the flag of Canada pales in comparison to the inclusion of the entire Royal Union Flag (Union Jack) in some granted Canadian coats of arms. The shield of the Royal Military College of Canada displays in centre the Union Jack on an escutcheon (also called Union badge or Union device) without any mark of difference (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1287&ShowAll=1). The shield of the City of Fredericton (New Brunswick) contains an escutcheon of the Union Jack and another of the Royal Arms of England, both topped by the royal crown (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1592&ShowAll=1). The top portion (the chief) of the shield of British Columbia features the Union devise differenced only with a small crown. The old badge of the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire (IODE) had a Union Jack escutcheon in centre which, interestingly, has since been replaced by a red maple leaf (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=2664&ShowAll=1).

One important role of heraldry is to mark allegiances. The arms of the Nova Scotia represent an excellent example of this. The shield replicates the flag of Scotland with the tinctures reversed while the escutcheon in centre shows the arms of Scotland intact. In light of this and the several unmodified replications of the United Kingdom’s flag as well as the use of a sprig of three red leave in Canadian emblems prior to 1965, it seems that the under secretary of state could have allowed the sprig of three maple leaves in the crest of the Royal Society of Canada. Clearly his apprehensions were not based on heraldic usage, but rather on the type of nitpicking often seen among persons in authority who have a fleeting encounter with heraldry.

Fig. 1. The Pearson Pennant, postcard published by L. Lebel, Ottawa, c. 1964, property of A. & P. Vachon.

Fig. 1. Le fanion de Pearson, carte postale publiée par L. Lebel, Ottawa, vers 1964, appartient à A. et P. Vachon.

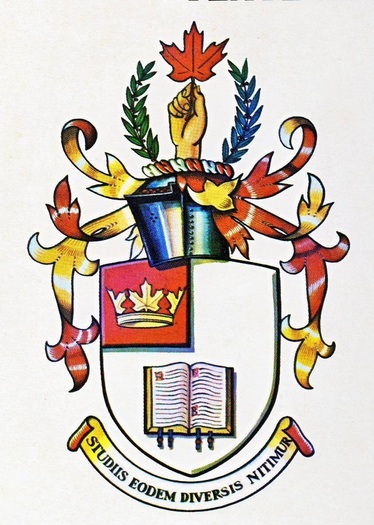

Fig. 2. A hand holding a single red maple leaf in the crest (above the helmet) of the arms of the Royal Society of Canada, granted by the Kings of Arms of England on 1 June 1965. Illustration from Beddoe's Canadian Heraldry (1981), p. 167.

Fig. 2. Une main tient une seule feuille d’érable rouge dans le cimier (au-dessus du casque) des armoiries de la Société royale du Canada, concédées par les rois d’armes d’Angleterre le 1 juin 1965. Illustration tirée de Beddoe's Canadian Heraldry (1981), p. 167.

Gestion d’un conflit héraldique

Le thème du numéro janv.-févr. 1990 de L’Archiviste portait sur les drapeaux historiques canadiens et, en particulier, sur le drapeau du Canada. William Kaye Lamb, bibliothécaire et archiviste national à la retraite, trouva ce numéro fort intéressant et voulut partager une expérience personnelle dans une lettre du 19 février adressée à Jean-Pierre Wallot, archiviste national. Il raconta que la Société royale du Canada avait décidé de se doter d’armoiries héraldiquement conformes et d’y inclure une branchette d’érable à trois feuilles rouges qu’elle avait arborée auparavant. L’héraldiste Alan Beddoe avait dessiné le tout selon les règles de l’art, mais comme il s’agissait d’une société constituée par charte royale, les responsables avaient sollicité l’accord du sous-secrétaire d’État. Le secrétaire s’y opposa prétextant que les trois feuilles allaient bientôt figurer dans le drapeau national et qu’une seule feuille conviendrait mieux. La société accepta sa proposition, mais au moment même où les hérauts de Londres préparaient les lettres d’armoiries, le comité responsable du choix d’un drapeau adoptait également une seule feuille, de sorte que la duplication ne put être évitée.

Le drapeau à trois feuilles, lancé par Pearson et surnommé « fanion de Pearson » [Pearson Pennant] (fig. 1), faisait l’objet d’un débat à la Chambre à partir du 15 juin 1964. Le refus d’autoriser les trois feuilles démontre que le sous-secrétaire d’État croyait fermement au triomphe imminent du choix de Pearson. Pourtant, le 22 octobre suivant, le comité du drapeau vota en faveur de l’unifolié éliminant ainsi le trifolié.

L’interdiction à la Société royale du Canada d’arborer trois feuilles d’érable était-elle fondée ? On peut en douter, car elles figuraient déjà dans l’héraldique canadienne, et pas seulement dans les armoiries du pays. Dès 1871, trois feuilles d’érable sur une tige au naturel, donc potentiellement rouges, apparaissaient dans la patte d’un lion servant de cimier à John Young, baron de Lisgar, deuxième gouverneur général du Canada. L’armée canadienne s’identifiait par un insigne à trois feuilles d’érable rouges depuis 1940 et l’unique feuille rouge sur fond blanc de la Légion royale canadienne précédait l’adoption du drapeau. Le fait d’inclure un élément du drapeau du pays dans les armoiries d’une société à caractère national est difficilement blâmable, d’autant plus que ce phénomène se retrouve dans plusieurs emblèmes homologués dont certains n’ont ni envergure nationale ni de lien avec le gouvernement. Après la proclamation de l’unifolié en 1965, l’écu concédé à la Société royale héraldique du Canada affichait un écusson blanc orné d’une feuille d’érable rouge (fig.2). Le Registre public des armoiries, drapeaux et insignes du Canada, créé en 1988, comprend les emblèmes d’un bon nombre d’organismes et de particuliers où figure une feuille d’érable rouge sur fond blanc. Citons, à titre d’exemple, l’insigne du Service canadien du renseignement de sécurité et l’insigne et certains drapeaux de la Garde côtière canadienne. Il en est de même pour les armoiries de l’École de la fonction publique du Canada, des Friends of Austria, de l’Association des Levasseur d’Amérique et des armoiries personnelles d’Andrew Austin Duncanson et de John Gerald Patrick Langton.

Sur l’échelle du mimétisme visuel, la présence de la feuille d’érable, à la fois dans le cimier de la Société royale du Canada et dans le drapeau national, ne peut se comparer à certaines armoiries canadiennes concédées avec le drapeau du Royaume-Uni transposé intégralement sur un écusson. C’est le cas des armoiries du Collège militaire du Canada qui porte au centre un tel écusson sans ajout (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=f&ProjectID=1287&ShowAll=1). De même, l’écu de la ville de Fredericton (Nouveau-Brunswick) renferme trois écussons dont l’un arbore l’Union Jack et l’autre les armoiries d’Angleterre, les deux écussons sommés de la couronne royale (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=f&ProjectID=1592&ShowAll=1). On retrouve également l’Union Jack brisé d’une petite couronne dans le haut (en chef) des armoiries de la Colombie-Britannique. L’ancien insigne de l'Ordre impérial des filles de l'Empire (IODE) affichait au centre l’Union Jack sur un écusson, maintenant remplacé par une feuille d’érable rouge (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=f&ProjectID=2664&ShowAll=1).

L’un des rôles majeurs de l’héraldique est de signaler des alliances ou allégeances. Les armoiries de la Nouvelle-Écosse offrent un excellent exemple de ceci. Elles reproduisent le drapeau de l’Écosse avec les émaux renversés et, au centre, les armoiries de l’Écosse sans modification. Étant donné la présence de trois feuilles d’érable rouges dans plusieurs emblèmes canadiens avant 1965, la réplication encore plus flagrante du drapeau du Royaume-Unis dans d’autres emblèmes et la notion d’alliance propre à l’héraldique, il semble que le sous-secrétaire d’État aurait pu approuver l’inclusion de la branchette d’érable dans le cimier des armoiries de la Société royale du Canada. Il paraît évident que sa crainte de commettre un impair ne relevait pas de l’usage héraldique, mais du genre de scrupule qu’on retrouve trop souvent chez des personnes en situation d’autorité qui sont exposés sommairement à la science du blason.

Le thème du numéro janv.-févr. 1990 de L’Archiviste portait sur les drapeaux historiques canadiens et, en particulier, sur le drapeau du Canada. William Kaye Lamb, bibliothécaire et archiviste national à la retraite, trouva ce numéro fort intéressant et voulut partager une expérience personnelle dans une lettre du 19 février adressée à Jean-Pierre Wallot, archiviste national. Il raconta que la Société royale du Canada avait décidé de se doter d’armoiries héraldiquement conformes et d’y inclure une branchette d’érable à trois feuilles rouges qu’elle avait arborée auparavant. L’héraldiste Alan Beddoe avait dessiné le tout selon les règles de l’art, mais comme il s’agissait d’une société constituée par charte royale, les responsables avaient sollicité l’accord du sous-secrétaire d’État. Le secrétaire s’y opposa prétextant que les trois feuilles allaient bientôt figurer dans le drapeau national et qu’une seule feuille conviendrait mieux. La société accepta sa proposition, mais au moment même où les hérauts de Londres préparaient les lettres d’armoiries, le comité responsable du choix d’un drapeau adoptait également une seule feuille, de sorte que la duplication ne put être évitée.

Le drapeau à trois feuilles, lancé par Pearson et surnommé « fanion de Pearson » [Pearson Pennant] (fig. 1), faisait l’objet d’un débat à la Chambre à partir du 15 juin 1964. Le refus d’autoriser les trois feuilles démontre que le sous-secrétaire d’État croyait fermement au triomphe imminent du choix de Pearson. Pourtant, le 22 octobre suivant, le comité du drapeau vota en faveur de l’unifolié éliminant ainsi le trifolié.

L’interdiction à la Société royale du Canada d’arborer trois feuilles d’érable était-elle fondée ? On peut en douter, car elles figuraient déjà dans l’héraldique canadienne, et pas seulement dans les armoiries du pays. Dès 1871, trois feuilles d’érable sur une tige au naturel, donc potentiellement rouges, apparaissaient dans la patte d’un lion servant de cimier à John Young, baron de Lisgar, deuxième gouverneur général du Canada. L’armée canadienne s’identifiait par un insigne à trois feuilles d’érable rouges depuis 1940 et l’unique feuille rouge sur fond blanc de la Légion royale canadienne précédait l’adoption du drapeau. Le fait d’inclure un élément du drapeau du pays dans les armoiries d’une société à caractère national est difficilement blâmable, d’autant plus que ce phénomène se retrouve dans plusieurs emblèmes homologués dont certains n’ont ni envergure nationale ni de lien avec le gouvernement. Après la proclamation de l’unifolié en 1965, l’écu concédé à la Société royale héraldique du Canada affichait un écusson blanc orné d’une feuille d’érable rouge (fig.2). Le Registre public des armoiries, drapeaux et insignes du Canada, créé en 1988, comprend les emblèmes d’un bon nombre d’organismes et de particuliers où figure une feuille d’érable rouge sur fond blanc. Citons, à titre d’exemple, l’insigne du Service canadien du renseignement de sécurité et l’insigne et certains drapeaux de la Garde côtière canadienne. Il en est de même pour les armoiries de l’École de la fonction publique du Canada, des Friends of Austria, de l’Association des Levasseur d’Amérique et des armoiries personnelles d’Andrew Austin Duncanson et de John Gerald Patrick Langton.

Sur l’échelle du mimétisme visuel, la présence de la feuille d’érable, à la fois dans le cimier de la Société royale du Canada et dans le drapeau national, ne peut se comparer à certaines armoiries canadiennes concédées avec le drapeau du Royaume-Uni transposé intégralement sur un écusson. C’est le cas des armoiries du Collège militaire du Canada qui porte au centre un tel écusson sans ajout (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=f&ProjectID=1287&ShowAll=1). De même, l’écu de la ville de Fredericton (Nouveau-Brunswick) renferme trois écussons dont l’un arbore l’Union Jack et l’autre les armoiries d’Angleterre, les deux écussons sommés de la couronne royale (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=f&ProjectID=1592&ShowAll=1). On retrouve également l’Union Jack brisé d’une petite couronne dans le haut (en chef) des armoiries de la Colombie-Britannique. L’ancien insigne de l'Ordre impérial des filles de l'Empire (IODE) affichait au centre l’Union Jack sur un écusson, maintenant remplacé par une feuille d’érable rouge (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=f&ProjectID=2664&ShowAll=1).

L’un des rôles majeurs de l’héraldique est de signaler des alliances ou allégeances. Les armoiries de la Nouvelle-Écosse offrent un excellent exemple de ceci. Elles reproduisent le drapeau de l’Écosse avec les émaux renversés et, au centre, les armoiries de l’Écosse sans modification. Étant donné la présence de trois feuilles d’érable rouges dans plusieurs emblèmes canadiens avant 1965, la réplication encore plus flagrante du drapeau du Royaume-Unis dans d’autres emblèmes et la notion d’alliance propre à l’héraldique, il semble que le sous-secrétaire d’État aurait pu approuver l’inclusion de la branchette d’érable dans le cimier des armoiries de la Société royale du Canada. Il paraît évident que sa crainte de commettre un impair ne relevait pas de l’usage héraldique, mais du genre de scrupule qu’on retrouve trop souvent chez des personnes en situation d’autorité qui sont exposés sommairement à la science du blason.