Dominion Shields

From the 1870s, the constant addition of devices to Canada’s shield as new provinces or territories joined Confederation was never authorized. “Dominion Shields” is chosen here as a title because this phraseology does not imply granted emblems to the extent that “Dominion Arms” would. A new development in Canadian national heraldry took place in 1921 when Canada acquired properly granted arms. The several publications of the Department of the Secretary of State for Canada on the granted arms are all titled The Arms of Canada rather than “The Arms of the Dominion of Canada.” I have also retained “Arms of Canada” for the next section which deals with modifications in style and augmentations to Canada’s 1921 arms.

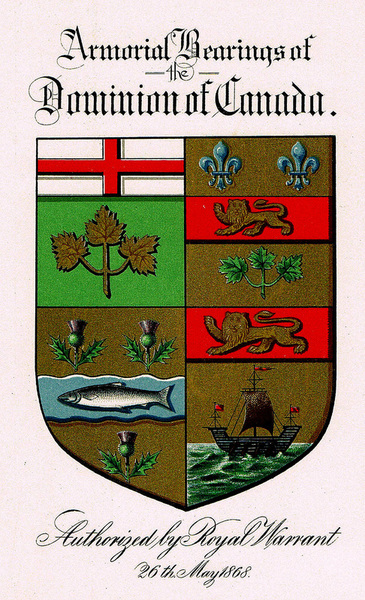

On 26 May 1868, a shield containing the quartered arms of Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick was assigned by royal warrant to serve as a common seal for the four confederated provinces called Dominion of Canada (fig. 1). When the seal of the new Dominion arrived from England, the arms of the provinces were there but separately, two on each side of Queen Victoria seated under a triple gothic canopy (fig. 2). Almost immediately, Canadians viewed the quartered arms (fig. 1) as those of the country and began using them as such. They further placed this shield in the fly of the Red Ensign to create what they considered to be a distinctive Canadian flag. As new provinces joined Confederation, whatever emblematic device they used was added to the shield. Strangely enough, the impression that the imagery lifted from seals or designed by amateurs constituted legitimate emblems was created to a large extent, as we shall see, by the British Colonial Office and the British Admiralty.

On 26 May 1868, a shield containing the quartered arms of Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick was assigned by royal warrant to serve as a common seal for the four confederated provinces called Dominion of Canada (fig. 1). When the seal of the new Dominion arrived from England, the arms of the provinces were there but separately, two on each side of Queen Victoria seated under a triple gothic canopy (fig. 2). Almost immediately, Canadians viewed the quartered arms (fig. 1) as those of the country and began using them as such. They further placed this shield in the fly of the Red Ensign to create what they considered to be a distinctive Canadian flag. As new provinces joined Confederation, whatever emblematic device they used was added to the shield. Strangely enough, the impression that the imagery lifted from seals or designed by amateurs constituted legitimate emblems was created to a large extent, as we shall see, by the British Colonial Office and the British Admiralty.

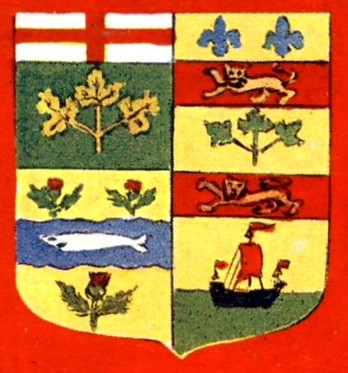

Fig. 1. Quartered arms of Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick assigned in 1868 to serve as a common seal for the new Dominion.

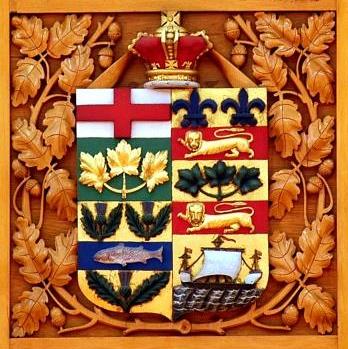

Fig. 1a. Dominion shield topped with the royal crown. Decorates the galleries of the Library of Parliament, 1876.

Fig. 2. Silver female die of the first Great Seal of Canada designed by the Wyon Brothers. The royal arms are in the base while those of the provinces are enclosed within the canopy on either side of Queen Victoria. The image has been flipped to provide a positive illustration that is easy to read.

Two important pieces of legislation had a huge impact on the quartered shield that Canada considered to be its legitimate armorial bearings. The Colonial Naval Defence Act of 1865 ruled that vessels owned or in the service of the colony were to fly the Blue Ensign with the badge or seal of the colony in the fly. This was followed by an order in council of Queen Victoria on 31 July 1869 authorizing the governors or administrators of British colonies to use the Union Jack with the badge of the colony in the centre. As a result, a series of dispatches from the secretaries of state for the colonies were sent to the governors general, lieutenant-governors, and administrators asking them to specify what they would use to identify the colony or province they represented. The dispatches clearly stated that the imagery from provincial or colonial seals or a badge would be entirely acceptable as distinctive emblems to be published in the Admiralty Flag Book. This conveyed the notion that whatever appeared on a seal or what might be adopted as a distinctive badge was on the same footing as officially granted arms and this very likely explains why such devices were added to the Dominion shield assigned in 1868 (fig. 1). For further information, see: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/chapter-3-the-dominion-shield.html

1. Augmentations to the Original Shield

In the 1870s, Canada was made up of the four original provinces to form Confederation, of the newly created province of Manitoba which joined Confederation in 1870 and of the provinces of British Columbia and Prince Edward Island which joined in 1871 and 1873 respectively. The rest of the country consisted of the Northwest Territories which had been ceded to Canada by the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1869.

These various territorial entities responded in different ways to their need for identification on the Blue Ensign and the flag of governors or administrators. Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick each used the coat of arms they were granted in 1868. Manitoba and Prince Edward Island derived an emblem from their seals, while British Columbia adopted a device of its own which was approved by the Admiralty on 9 July 1870. Although Newfoundland had arms since 1637 and could have used its shield portion, it chose badges specifically for that purpose. The badge of Newfoundland did not enter the Dominion shield because the island did not join the Canadian Confederation until 1949.

In the 1870s, Canada was made up of the four original provinces to form Confederation, of the newly created province of Manitoba which joined Confederation in 1870 and of the provinces of British Columbia and Prince Edward Island which joined in 1871 and 1873 respectively. The rest of the country consisted of the Northwest Territories which had been ceded to Canada by the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1869.

These various territorial entities responded in different ways to their need for identification on the Blue Ensign and the flag of governors or administrators. Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick each used the coat of arms they were granted in 1868. Manitoba and Prince Edward Island derived an emblem from their seals, while British Columbia adopted a device of its own which was approved by the Admiralty on 9 July 1870. Although Newfoundland had arms since 1637 and could have used its shield portion, it chose badges specifically for that purpose. The badge of Newfoundland did not enter the Dominion shield because the island did not join the Canadian Confederation until 1949.

Fig. 3. The five-province shield of the Dominion, c. 1873 to 1874.

Figure 3 displays the shield of the Dominion as it appeared in the tennis court and ballroom of Rideau Hall, the latter being opened in March of 1873. The illustration is from the article “State and Society in Ottawa” in Lippincott’s Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, June 1879, p. 656. The emblem of Manitoba in the last quarter is derived from its provincial seal and is seen added to the Dominion shield, perhaps for the first time, on the front page of L'Opinion publique of 2 January 1873.

Fig. 4. The seven-province shield of the Dominion from 1874 to c. 1915.

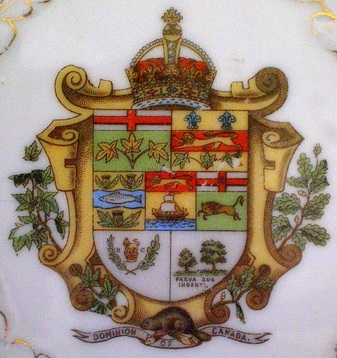

Figure 4 displays the quarters of the four original provinces to which are added depictions of the seals of Manitoba and Prince Edward Island, and the device adopted by British Columbia in 1870. The arrangement is: 1st row, Ontario and Quebec, 2nd row, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Manitoba; 3d row, British Columbia and Prince Edward Island. In some versions of Manitoba, the crown is omitted from the centre of the red St. George cross. As usual the royal crown tops the shield. This seven-province shield appeared on the front page of the Canadian Illustrated News of 5 December 1874. The same shield within a wreath of maple branches, with the royal crown on top and a beaver below, was featured on the medal of the Dominion of Canada at the Philadelphia exhibition of 1876. This combination should have gone out of existence after arms were granted to other provinces from 1905 to 1907, but it survived for several years.

Fig. 5. The same shield as fig. 4 within a wreath of maple branches. On a Wedgwood plate dated 1917.

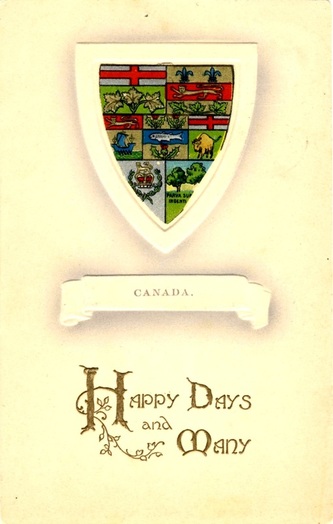

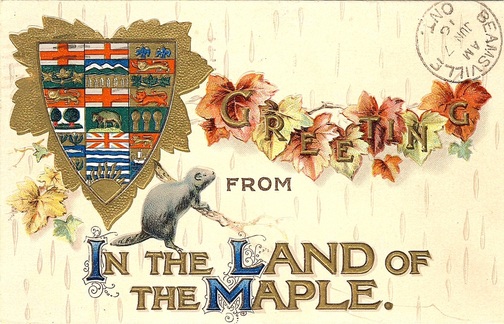

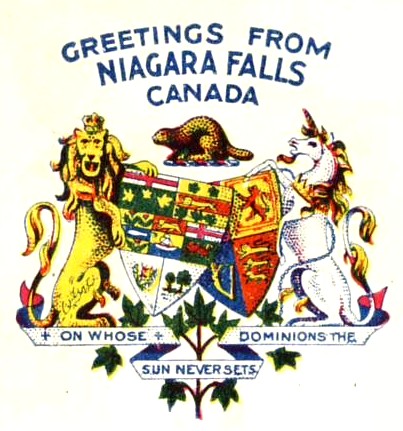

Fig. 6. This greeting postcard helps confirm that the seven-province shield was around long after the remainder of Canadian provinces were granted arms by Edward VII between May 1905 and May 1907. It is postmarked Dec. 04 (or 14) 1917. It further has an inscription relating to the 1918 New Year, see figure 7.

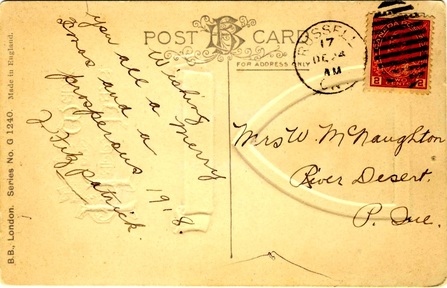

Fig. 7. Back of figure 6. The name of the company and series number is marked on the left margin. The same company made several similar greeting cards with the shield of Canada or that of one of its provinces. River Desert in the address is the former name of Maniwaki, Quebec.

Fig. 8. Another version of the shield of the Dominion from 1874 to c. 1915. From a side plate by Schmidt & Co., Altrohlau (Bohemia), c.1901.

In figure 8, the shield is on a cartouche, the royal crown sits on the shield, a branch of oak and a branch of maple are added on the sides and a beaver on a log below. The illustration dates from 1901 or later based on the shape of the crown. A postcard illustrated with the same arms by Nerlich & Co. of Toronto is postdated 27 July 1901, see: http://www.vintagepostcards.ca/Nerlich_S2.html.

Fig. 9. Dominion of Canada shield as displayed on the bow badge of the British Warship H.M.S. Canada. This photograph being rather old, the background colours are not clear. Fortunately the badge has since been restored. For further information and more recent photographs, see: http://www.nauticapedia.ca/Gallery/Canada_HMS.php and http://www.flagsforum.com/viewtopic.php?t=889.

One of the strangest armorial concoctions to ever grace the seas is the composite shield of the Dominion of Canada as seen on the bow badge of the British Warship H.M.S. Canada which was launched in 1881 and remained in service until 1897 (fig. 9). The badge was a gift by the Dominion of Canada to the shipbuilding company when the ship was launched. Before the ship was sold, the badge was removed and kept in storage until 1954. It was then retrieved by the Curator of the Royal Naval Museum in Portsmouth and presented to the Maritime Museum of British Columbia where it is displayed. The armorial quarters are from left to right: 1st row: Nova Scotia and Quebec (both granted); 2nd row: Prince Edward Island (from seal), New Brunswick (granted), British Columbia (adopted 1870); 3d row: Ontario (granted) and Manitoba (adopted in early 1880’s). The maple leaves in base of the arms of Quebec are oval shaped and the device of Prince Edward Island is presented in the manner of country scenery.

Fig. 10. A new version of the Dominion shield from c. 1903. Unmarked plate made in Austria or Germany.

This version of the Dominion shield (fig. 10) was in existence in 1903 as demonstrated on the obverse of a medal presented by the Toronto Industrial Exhibition Association to commemorate the Dominion of Canada Industrial Exhibition. The piece is marked 1903 in large numbers and struck by P. W. Ellis & Co. (Library and Archives Canada, Laurier Collection, medal 5778, photo C 53742). The same composition also appears in an advertisement of the Confederation Life Association on the back cover of the Canadian Almanac of 1903. The arrangement of the quarters is as follows: 1st row from left to right: Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia; 2nd row: New Brunswick (all four official), British Columbia (unofficial designed by Arthur John Beanlands), Prince Edward Island; 3d row: Northwest Territories, Yukon (the last three are unofficial Edward Marion Chadwick creations) and Manitoba (unofficial from its seal). I have not found the creations of Beanlands nor Chadwick on the Dominion shield prior to 1903. For information on Beanlands and Chadwick, see their names in the “Who was Who? of Canadian Heraldry”: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/b.html and http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/c.html.

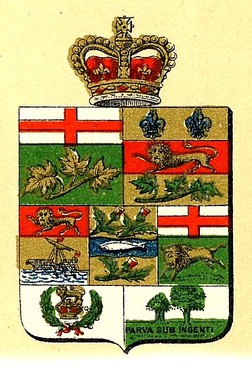

Fig. 11. All the arms on this shield are granted except those of the Yukon in the middle upper row. Alberta, which was granted arms on 30 May 1907, is missing. Wedgwood plate 1908.

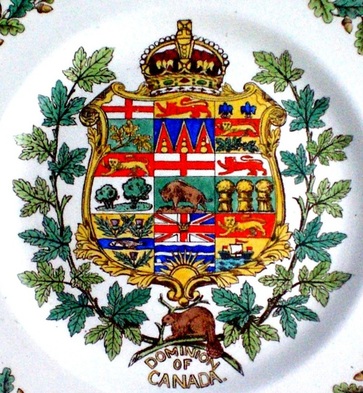

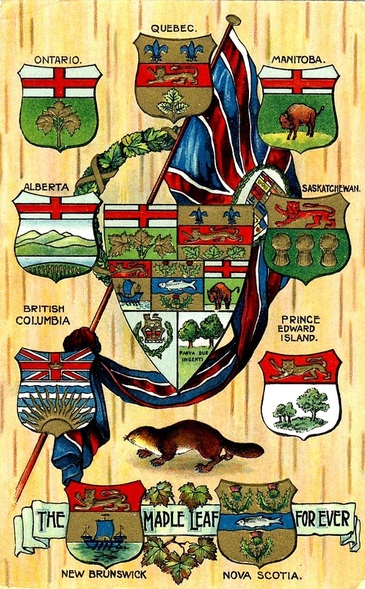

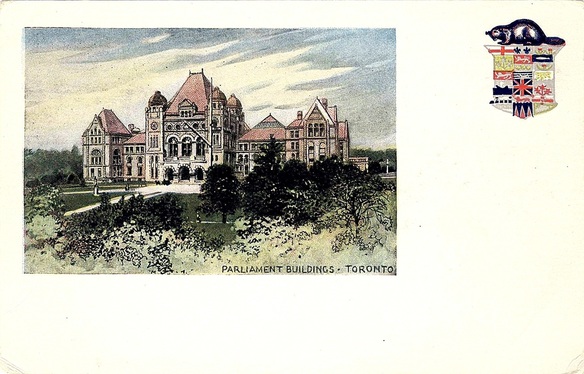

Fig. 12. A nine-province shield with all arms granted, placed on a maple leaf accompanied by a beaver. Postcard of the B. B. London Series, printed in Germany, postmarked 7 June 1910, with stamps of George V who became king that year.

The quarters are as follows: 1st row: Ontario, Alberta, Quebec; 2nd row: Prince Edward Island, Manitoba, Saskatchewan; 3d row: Nova Scotia, British Columbia, New Brunswick. Although not in the best taste, this postcard reflects a strong national sentiment, at least for the Anglophone Canadians of the time. As in figure 13, the background imitates birch bark.

Fig. 13. Postcard by The Illustrated Post Card Company of Montreal, after May 1907.

Figure 13 demonstrates again that the seven-province Dominion shield, in use from c. 1876, continued to thrive after all the provinces possessed granted arms. Here the Dominion shield is surrounded by the granted arms of all the provinces, the last grant being to Alberta on 30 May 1907. The proliferation of official arms mingled with devices of all kinds was confusing for Canadians, all the more so that the constantly modified shield used to represent Canada had no official status. In the background of the postcard, the seven-province shield also appears on the Union Jack. No doubt the flag of the Governor General of Canada is intended, but only a four province shield was authorized for that purpose. The background is an imitation of birch bark. The animal seems to be a mink. Almost everything Canadian is there: a wreath of maple leaves behind the shield and more maple leaves with a scroll inscribed “THE MAPLE LEAF FOREVER.”

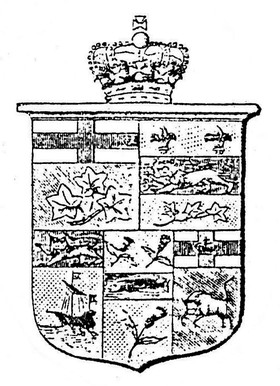

Fig. 14. Four-province shield, print by Mortimer and Co., 1904

In an effort to stem the rainbow of colours appearing in the Dominion shield, Sir Joseph Pope had this four-province shield printed in 1904 by Mortimer and Co. (fig. 14). At the time, he was convinced that Canada had been granted arms in this form by the Royal Warrant of 1868. Following Popes offensive, a certain number of four-province shield began appearing particularly on postcards, but shields with seven quarters or more continued to be used, see figures 11 to 13.

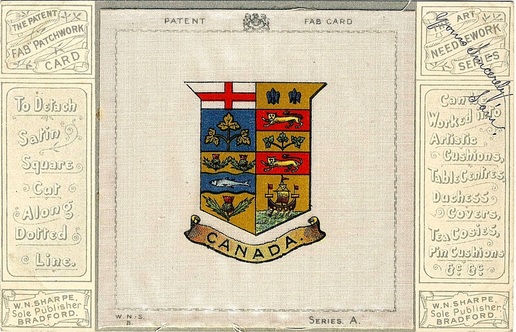

Fig. 15. This card, published in Bradford (England) c. 1910, illustrates an applied art side to heraldry. It contains clear instructions for removing the arms printed on silk and what can be done with them. Unfortunately the leafy twig of maple in the arms of Ontario should be on a green field, not a blue one.

Fig. 16. Front of a postcard folder published by H.V. Henderson, West Bathurst, New Brunswick, 1934 or later.

Figure 16 presents an example, and not a unique one, where the four province shield continued in use a number of years after Canada had been granted a proper achievement of arms in 1921. The folder of postcards contains the memorial granite cross of Jacques Cartier which was erected in 1934 at Gaspé, overlooking Gaspé Harbour where Cartier planted his original wooden cross, four centuries earlier in 1534. On souvenirs, the figure of the Royal Canadian Mounted police became popular in the second half of the twentieth century.

2. Dominion Shield with Added Supporters and Crest

What follows is a sampling of supporters added to the Dominion shield. The addition of supporters was not that frequent, but these additions came in several types. The favourite crest to add above the shield was the beaver when the royal crown was not there.

What follows is a sampling of supporters added to the Dominion shield. The addition of supporters was not that frequent, but these additions came in several types. The favourite crest to add above the shield was the beaver when the royal crown was not there.

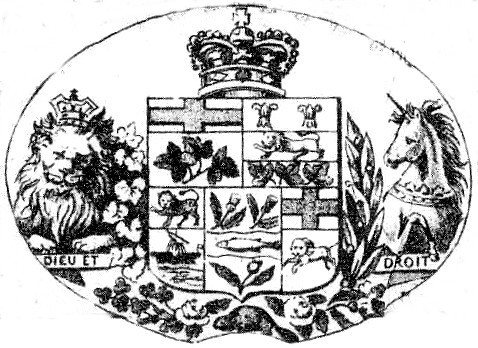

Fig. 17. Five-province shield with the addition of the supporters and motto of the United Kingdom. The motto Dieu et mon droit was originally a battle cry. From “Bird's eye view of the City of Ottawa… 1876” drawn by Herm. Brosius.

Fig. 18. The arms of the Dominion, in use from 1876 to c. 1905, augmented with the usual crown, beavers as supporters and a motto. The floral badges of England, Scotland and Ireland, mixed with maple leaves, appear around the motto scroll, an idea which will be retained for the arms granted to Canada in 1921. Illustration from Horace T. Martin, Castorologia (Montreal: Wm. Drysdale & Co., 1892), p. 201. It is signed ''HTM'' in the lower left.

Fig. 19. Nine-province shield (all granted arms) held by the divinities Ceres and Mercury on the façade of the Dominion Express Building, built in 1912 on St-Jacques St., Montreal. Illustration from Gonfanon vol. 18, no. 2 (Summer 2007), p. 16.

|

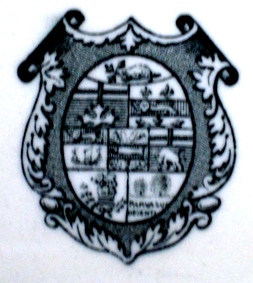

Fig. 20. Portrait plate of the Right Hon. John A. Macdonald K.C. B., Prime Minister of Canada, attributed to Wallis Gimson & Co., England. Dated in or prior to 1884 when Sir John A. became a G.C.B. A plate in the same series is dedicated to the Hon. Edward Blake, M.A., Q.C., Liberal Leader of the Opposition. The shield of the Dominion is within a cartouche and is topped with a beaver holding a sprig of maple in the mouth. |

Fig. 21. A beaver is featured on top of this Dominion shield. Detail of a bone china cup and saucer by Myott and Royal Grafton China, England, c. 1905.

3. The Dominion Shield Mixed With Emblems of Great Britain

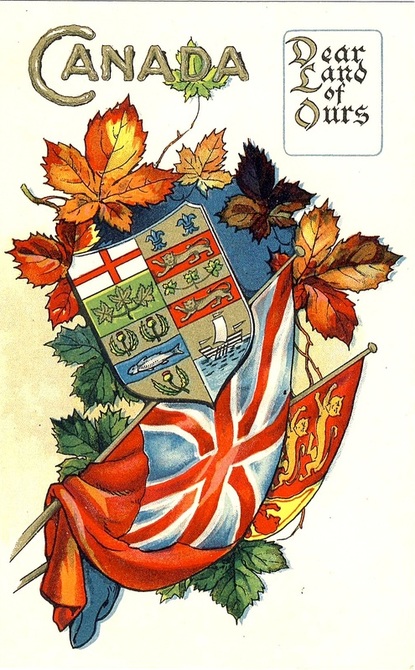

Fig. 23. This postcard with the Dominion shield and maple leaves expresses strong Canadian sentiments with nostalgia for Britain by the presence of the Red Ensign and the Royal Standard which is the sovereign’s personal banner. “National Series” published in Great Britain, No. 2261, c. 1905-1910.

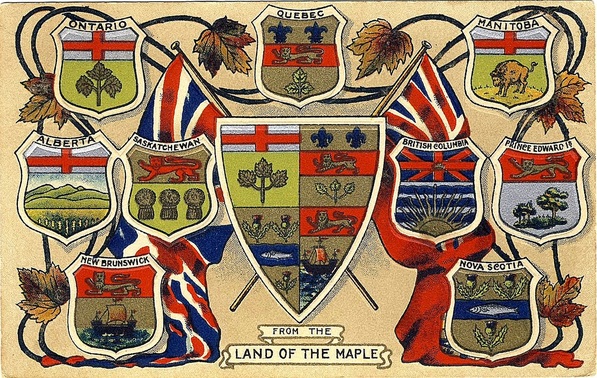

Fig. 24. The Union Jack mingles with the Dominion shield, the shields of the nine provinces, maple leaves and the Canadian Red Ensign on this postcard. Printed in Great Britain for The Valentine & Sons Publishing Co., Ltd., Montreal and Toronto, postmarked 1913.

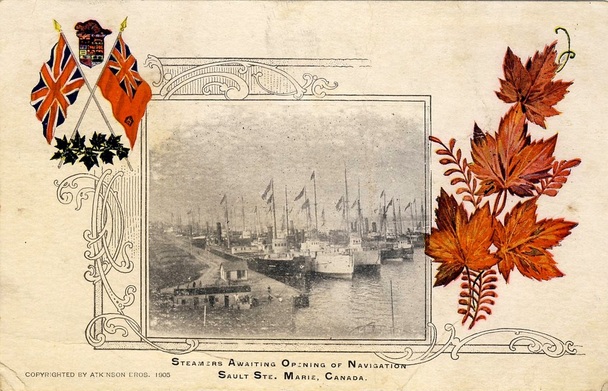

Fig. 25. The seven-province Dominion shield topped by a beaver crest is set between the flagpoles of the Union Jack and Canadian Red Ensign with a garland of maple leaves in base. Postcard by Atkinson Bros, 1905.

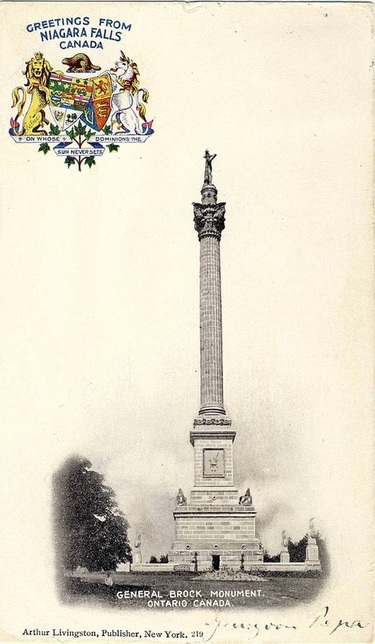

Fig. 26. Many companies published postcards with the shield of the Dominion overlapping the shield of Britain, the British supporters, and the beaver as a crest, This one was printed by Arthur Livingston of New York and is postmarked 1904.

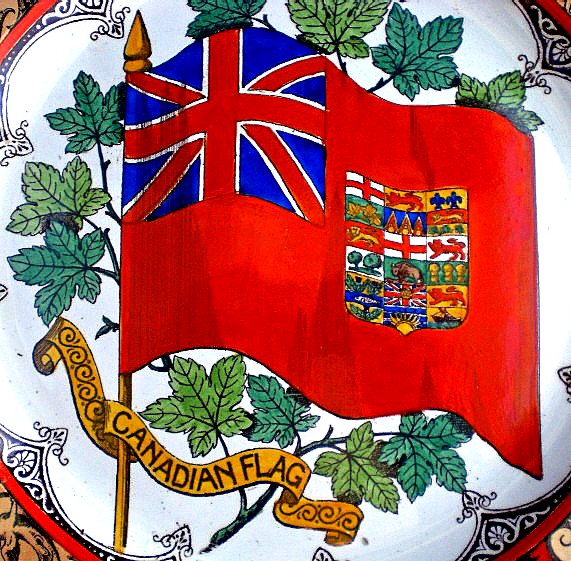

4. The Dominion Shield in the Fly of the Red Ensign

Most of the successive shields of the Dominion have appeared in the fly of the Red Ensign. A thorough and well illustrated study of this phenomenon is found on the site: http://imperialflags.blogspot.ca/2010/01/british-empire-flags.html. The examples below appeared in printed form.

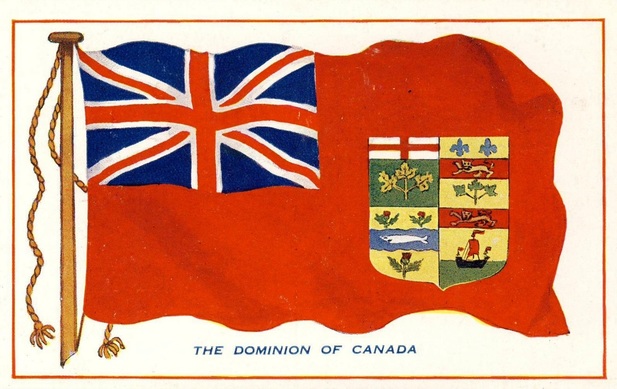

Fig. 27. The Canadianized Red Ensign as flown c. 1870 and in the early years of the twentieth century. Postcard “The Milton ‘Topical’ Series no. 17” by Woolstone Bros., London, England, c. 1910.

Fig. 28. Four-province shield with royal crown. Postcard by Raphael Tuck & Sons, postmarked Victoria B.C., August 3, 1908.

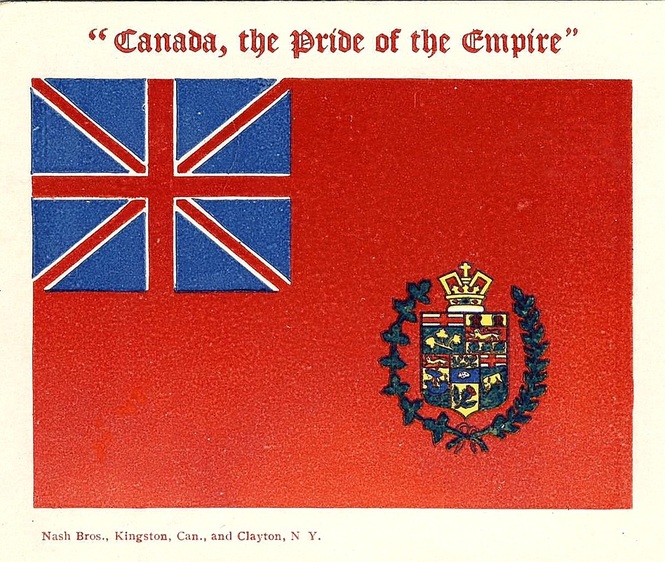

Fig. 29. Five-province shield with four granted arms and the device of Manitoba as in figure 3, with a crown and a wreath of maple and oak added. This shield was in use from c. 1873 to c. 1876. As in many other depictions of the Union Jack, the saltire cross of St. Andrew is not clearly represented (see also fig. 31). Postcard by Nash Bros., Kingston, Ontario, and Clayton New York.

Fig. 30. Seven-quarter shield in the fly of the Red Ensign, as in figures 4-6 and 7. Postcard published by Stedman Bros. Ltd, Brantford, Canada. Printed in Germany, c. 1910.

Fig. 31. Eight granted arms and Yukon, with Alberta missing. On a 1909 plate by Wedgwood, England.

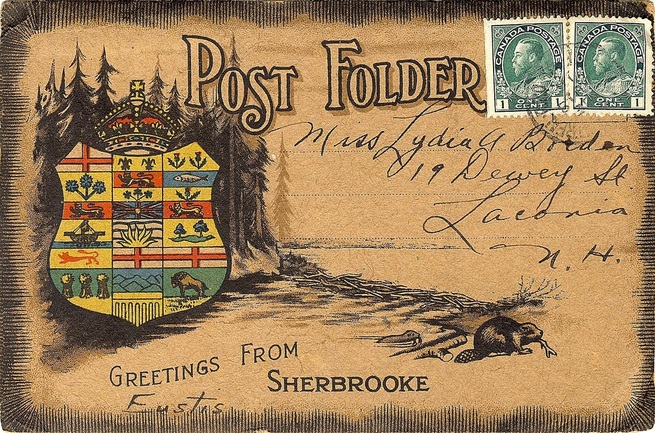

Fig. 32. Nine granted arms on a shield in the fly of the Red Ensign and also the Blue Ensign. Back of a postcard folder dedicated to Sherbrooke. The front of the folder, figure 33, displays a clearer image of the nine-province shield.

Fig. 33. Nine-province shield with all granted arms, ensigned by the royal crown. Front of a postcard folder (see fig. 32). The scenery includes a beaver dam and two beavers. The stamps with the effigy of King George V are dated 1912-1925, but these types of postcards were mostly produced prior to the First World War, therefore, c. 1912-14.

5. Picture sources

Library of Parliament, © Library of Parliament / Mone Cheng: fig. 1a.

Library and Archives Canada: figs. 2 (photo C-6792), 17.

Canadian Museum of History, Vachon Collection: figs. 5, 8, 10-11, 20-21, 30.

Auguste and Paula Vachon: figs. 1, 4, 6-7, 12-16, 22-29, 31-33.

Nota Bene

All the websites referred to above were accessed on 27 April 2016.

Work of Related Interest

W.L. Gutzman. The Canadian Patriotic Post Card Handbook 1904-1914. 1st ed. Toronto: The Unitrade Press, 1985.

Library of Parliament, © Library of Parliament / Mone Cheng: fig. 1a.

Library and Archives Canada: figs. 2 (photo C-6792), 17.

Canadian Museum of History, Vachon Collection: figs. 5, 8, 10-11, 20-21, 30.

Auguste and Paula Vachon: figs. 1, 4, 6-7, 12-16, 22-29, 31-33.

Nota Bene

All the websites referred to above were accessed on 27 April 2016.

Work of Related Interest

W.L. Gutzman. The Canadian Patriotic Post Card Handbook 1904-1914. 1st ed. Toronto: The Unitrade Press, 1985.