Chapter 1

European Heritage

In Canada, the First Nations possessed their own emblems prior to the arrival of Europeans in the New World. These had evolved into complex systems, reflecting their customs and beliefs. Though the term heraldry is sometimes loosely applied to these emblematic traditions, they are not heraldry in the Europeans sense. For identification on the battlefield, Medieval Europe developed a highly specialized and specific art, which was also a science with its own structure and terminology. This art and science survived to this day and was transmitted to the Americas by the colonizing powers and by immigrating families who possessed coats of arms. Though heraldry is of European origin, it can include symbols from other cultures including those of First Nations, which are already beautifully stylised in a way that can blend harmoniously with heraldic art.

1. Native Emblems

Native emblems are complex and specialized and, like European heraldry, are linked to tradition and family. The totemic emblems of important chiefs appeared on a large number of the treaties signed with Europeans. A fine example of the blending of traditions is exemplified by the seal of Joseph Brant, a well known First Nations Loyalist. The Mohawk chief used a seal, a European practice, to display the totems of his clans, the turtle, the wolf, and the bear (fig. 1). While it is interesting to compare the heraldic systems of Europe with the emblems of First Nations and to discover parallels, it is ludicrous to try to assimilate one to the other, because they belong to very different origins.

1. Native Emblems

Native emblems are complex and specialized and, like European heraldry, are linked to tradition and family. The totemic emblems of important chiefs appeared on a large number of the treaties signed with Europeans. A fine example of the blending of traditions is exemplified by the seal of Joseph Brant, a well known First Nations Loyalist. The Mohawk chief used a seal, a European practice, to display the totems of his clans, the turtle, the wolf, and the bear (fig. 1). While it is interesting to compare the heraldic systems of Europe with the emblems of First Nations and to discover parallels, it is ludicrous to try to assimilate one to the other, because they belong to very different origins.

Fig. 1 Seal of Joseph Brant displaying a turtle, a wolf, and a bear representing the clans of his Mohawk tribe. Library and Archives Canada.

Some early explorers, such as Baron de Lahontan who spent ten years in New France (1683-93), went so far as to ridicule First Nations emblems on the grounds that they did not correspond to the canons of European heraldry:

“After a perusal of the former Accounts I sent you of the Ignorance of the Savages with reference to Sciences, you will not think it strange that they are unacquainted with Heraldry. The Figures you have represented in this Cut [engraving] will certainly appear ridiculous to you, and indeed they are nothing less: But after all you’ll content yourself with excusing these poor Wretches, without rallying upon their extravagant Fancies.”[1]

Between 1659 and 1661, John Gibbon, who later was to become Bluemantle Pursuivant at the College of Arms in England, journeyed to Virginia as a guest of Colonel Richard Lee. As he observed the ceremonial dances of the Amerindians, he noticed that that he could describe some of the body paintings and shields in heraldic terms. He concluded that, “heraldry was ingrafted naturally into the sense of human Race”.[2] In fact, heraldic language is a powerful instrument to describe imagery, which makes possible the description of some emblems from various emblematic traditions, and occasionally, other visual forms such as pieces of clothing, ties for instance, and other forms of design, even the odd painting. No doubt, a degree of coincidence comes into play, but beyond that, it seems normal that humans should express their creativity in similar ways, so that the structure of their creations at times corresponds closely enough to heraldry to be described in heraldic language.

Since its creation in 1988, the Canadian Heraldic Authority has granted many emblems which incorporate First Nations symbols to traditional European heraldry. However, for emblems that are distinctively First Nations, it has created a special register recognizing the specificity of their emblematic systems.

2. European Origins of Heraldry

In the European tradition, coats of arms, also termed armorial bearings, armorial ensigns or simply arms, came into use as a necessity during medieval warfare. The knight whose body, including his face, was entirely enclosed in armour needed a highly visible mark to be recognized as friend of foe on the battlefield. To this end, he painted distinctive marks on his shield, banner and surcoat: a coat worn over armour, hence the expression “coat of arms”. On his helmet, which was covered by a piece of cloth for protection from the sun's rays, he placed a figure, often an animal made of wood or boiled leather, which provided further identification. These markings were often repeated on the trappings of the horse, including the helmet figure (crest) perched on the horse’s head. Thus, both knight and horse were clearly identified, the latter being a valuable piece of property.

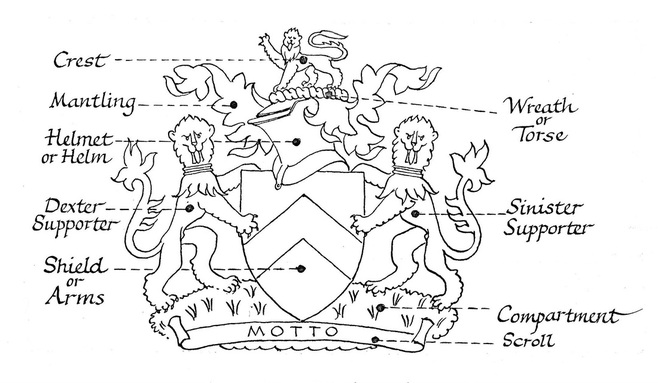

Today, a modern coat of arms is almost entirely derived from the knight's accoutrement. The shield, the helmet, the mantling (piece of cloth on helmet), the crest (helmet figure) and the crest wreath (a circle of two different coloured ropes twisted and placed between the mantling and crest) all come directly from the knight's armour. Some mottoes such as Dieu et mon droit (England) and Montjoie Saint-Denis (France) were obviously war cries, but most mottoes are of a different source as they express moral or pious sentiments. In early days, they were a feature of an important household's identity along with household badges and liveries.

The supporters, animals or humans and sometimes objects holding the shield on both sides and seemingly protecting it, do not necessarily come from the battlefield. One theory is that supporters originated from the tendency in Romanesque art to fill empty spaces with decorative animals. When the oblong shield was placed on the usually round surface of a seal, it left some unused space on both sides that engravers filled with decorative animals. Beyond their decorative value, these animals came to be associated with the shield and to the family by extension. Another theory is that animals were taken from badges, where they were frequent, to act as supporters for the shield. Other authors believe that supporters grew out of the pas d’armes, a minor sort of tournament that confronted a limited number of knights having challenged one another. The participating knights were required to hang their shields from posts to be examined by challengers who would verify the opponent’s titles of nobility. These shields were guarded by squires or pageboys dressed as lions, griffins, sirens or other real or imaginary animals. The theory is that these creatures eventually have found their way on both sides of the heraldic shield.[3] Even today, most supporters are animals. The compartment, usually a mound, is the support for the supporters, but it also ties together the supporters, the motto scroll, and the tip of the shield (fig. 2).

“After a perusal of the former Accounts I sent you of the Ignorance of the Savages with reference to Sciences, you will not think it strange that they are unacquainted with Heraldry. The Figures you have represented in this Cut [engraving] will certainly appear ridiculous to you, and indeed they are nothing less: But after all you’ll content yourself with excusing these poor Wretches, without rallying upon their extravagant Fancies.”[1]

Between 1659 and 1661, John Gibbon, who later was to become Bluemantle Pursuivant at the College of Arms in England, journeyed to Virginia as a guest of Colonel Richard Lee. As he observed the ceremonial dances of the Amerindians, he noticed that that he could describe some of the body paintings and shields in heraldic terms. He concluded that, “heraldry was ingrafted naturally into the sense of human Race”.[2] In fact, heraldic language is a powerful instrument to describe imagery, which makes possible the description of some emblems from various emblematic traditions, and occasionally, other visual forms such as pieces of clothing, ties for instance, and other forms of design, even the odd painting. No doubt, a degree of coincidence comes into play, but beyond that, it seems normal that humans should express their creativity in similar ways, so that the structure of their creations at times corresponds closely enough to heraldry to be described in heraldic language.

Since its creation in 1988, the Canadian Heraldic Authority has granted many emblems which incorporate First Nations symbols to traditional European heraldry. However, for emblems that are distinctively First Nations, it has created a special register recognizing the specificity of their emblematic systems.

2. European Origins of Heraldry

In the European tradition, coats of arms, also termed armorial bearings, armorial ensigns or simply arms, came into use as a necessity during medieval warfare. The knight whose body, including his face, was entirely enclosed in armour needed a highly visible mark to be recognized as friend of foe on the battlefield. To this end, he painted distinctive marks on his shield, banner and surcoat: a coat worn over armour, hence the expression “coat of arms”. On his helmet, which was covered by a piece of cloth for protection from the sun's rays, he placed a figure, often an animal made of wood or boiled leather, which provided further identification. These markings were often repeated on the trappings of the horse, including the helmet figure (crest) perched on the horse’s head. Thus, both knight and horse were clearly identified, the latter being a valuable piece of property.

Today, a modern coat of arms is almost entirely derived from the knight's accoutrement. The shield, the helmet, the mantling (piece of cloth on helmet), the crest (helmet figure) and the crest wreath (a circle of two different coloured ropes twisted and placed between the mantling and crest) all come directly from the knight's armour. Some mottoes such as Dieu et mon droit (England) and Montjoie Saint-Denis (France) were obviously war cries, but most mottoes are of a different source as they express moral or pious sentiments. In early days, they were a feature of an important household's identity along with household badges and liveries.

The supporters, animals or humans and sometimes objects holding the shield on both sides and seemingly protecting it, do not necessarily come from the battlefield. One theory is that supporters originated from the tendency in Romanesque art to fill empty spaces with decorative animals. When the oblong shield was placed on the usually round surface of a seal, it left some unused space on both sides that engravers filled with decorative animals. Beyond their decorative value, these animals came to be associated with the shield and to the family by extension. Another theory is that animals were taken from badges, where they were frequent, to act as supporters for the shield. Other authors believe that supporters grew out of the pas d’armes, a minor sort of tournament that confronted a limited number of knights having challenged one another. The participating knights were required to hang their shields from posts to be examined by challengers who would verify the opponent’s titles of nobility. These shields were guarded by squires or pageboys dressed as lions, griffins, sirens or other real or imaginary animals. The theory is that these creatures eventually have found their way on both sides of the heraldic shield.[3] Even today, most supporters are animals. The compartment, usually a mound, is the support for the supporters, but it also ties together the supporters, the motto scroll, and the tip of the shield (fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Components of a full coat of arms also called achievement of arms. From the original manuscript for Beddoe’s Canadian Heraldry entitled: Our Unknown Heritage: Heraldry in Canada, copy in possession of A. Vachon.

Heralds developed a specialized language to describe the shield of arms of the knights who participated in tournaments. The shields often featured geometric figures such as crosses and chevrons, animals such as lions and unicorns, celestial figures such as stars and crescents, and plants such as oak trees and roses. Flags to a large extent adopted the rules and aesthetics developed for medieval shields of arms.

The rules of heraldry require that only a limited number of elements be placed on a shield, that they be arranged symmetrically even if this entails repeating some elements. The whole combination of shield, motto, crest and supporters should be striking and pleasing. In order that the colours stand out, a metal, or (yellow) and argent (white) should never be placed on a metal, nor a colour on a colour, these being azure (blue), gules (red), sable (black) and vert (green). The essentials of the medieval heraldic system were transmitted to modern times. When a talented heraldic artist stylizes the components, adjusts the proportions and colour tones, the result can be stunning. Those who would judge this form of art to be too gaudy should remember that the primary objective of heraldry is instant recognition even at a distance.

3. Emblems of Early Explorers

A Danish raven or an Irish symbol may have adorned the first flag raised on what is now Canadian soil. It is now clear that Norsemen and possibly Irish monks were here long before the known explorers. In some recorded accounts, the place of landing is not clear. Historians have long speculated as to where John Cabot landed in 1497: what is now Canadian soil or the coast of Maine? Portuguese insignia may have been brought to the Canadian east coast by Gaspar Corte Real in 1501, Spanish insignia by Estavao Gomes in 1524 and French insignia by Giovanni da Verrazzano that same year. Breton fisherman had reached North American shores as early as 1504. In 1508, Thomas Aubert, an explorer from Dieppe, who located the fishing banks of Bonavista for Norman fishermen, brought the first Amerindians to set foot in Europe to his native province of Normandy. Basques may also have displayed their colours here before the official discovery of Canada.[4]

4. France’s Emblems in New France

4.1 Royal Arms at Land Claims

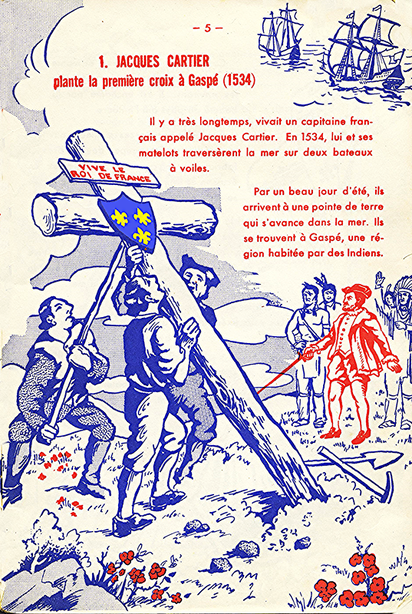

The first recorded land claiming ceremony to have unfolded indubitably on Canadian soil and to involve heraldry took place at the time of the official discovery of Canada. The coast of North America had been explored and chartered long before the arrival of Jacques Cartier, an explorer from Saint-Malo (Brittany). He is credited as the discoverer of Canada because he explored the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Gaspé Bay in 1534, and the next year, he followed the river into the interior of the continent. He planted at least five crosses during his voyages in 1534 and 1535-36, the best known instances being on the Gaspé coast on 24 July 1534 and at Stadacona (Quebec) on 3 May 1536. Both ceremonies mention a cross bearing a shield of the royal arms of France which was blue with three gold fleurs-de-lis. The Gaspé ceremony is described as follows:

“On [Friday] the twenty-fourth of the said month [of July], we had a cross made thirty feet high, which was put together in the presence of a number of the Indians on the point at the entrance to this harbour, under the cross-bar of which we fixed a shield with three fleurs-de-lys in relief, and above it a wooden board, engraved in large Gothic characters, where was written, LONG LIVE THE KING OF FRANCE.” [5]

After wintering at Stadacona (Quebec) in 1536, Cartier planted a similar cross:

“On [Wednesday¨] May 3, which was the festival of the Holy Cross, the Captain in celebration of this solemn feast, had a beautiful cross erected some thirty-five feet high, under the cross-bar of which was attached an escutcheon, embossed with the arms of France, whereon was printed in Roman characters: LONG LIVE FRANCIS I. BY GOD’S GRACE KING OF FRANCE.”[6]

In a less formal fashion, Cartier planted a number of other crosses which as it seems were intended as beacons or landmarks.[7]

Fig 2(a) On 24 July 1534, on the Gaspé coast, Jacques Cartier raises a cross bearing the Royal Arms of France to lay claim to the surrounding territory. Source: Ils ont fait notre pays : Histoire du Canada, manuel de 3e année (Montreal, Les Frères des écoles chrétiennes, 1953), p. 5.

Following Cartier's unsuccessful attempts on the St. Lawrence, Florida was chosen for the next colonization venture of France in North America. This was a first French attempt at creating an empire extending from Canada to Florida. This dream is illustrated on maps of the Americas by Abraham Ortelius published from 1570 to 1587, where New France is depicted as extending up to Florida, and beyond on certain of his maps.[8] The promoter was the Huguenot French patriot, Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, an avowed rival of Spain. He was supported financially by the most influential members of the French court. The commander, Jean Ribaut (Ribault) of Dieppe, also a Huguenot, was one of France's most capable seamen. On the first of May 1562, a day after reaching Florida near present day St. Augustine, Ribaut entered the mouth of the St. Johns River where he erected an octagonal stone column adorned on four angles with the royal arms of France surrounded by the Order of Saint-Michel. When Captain René de Laudonnière returned to the site two years later, the Indians brought the French before the column, which was now surrounded with offerings of fruit, food, medicinal herbs, jugs of perfumed oils and bows and arrows. After greeting and kissing this recent divinity, the chief invited his hosts to do the same. The scene has been captured by the artist Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues and published as an engraving in Theodore de Bry's second volume of the America series.[9]

In the summer of 1608, Samuel de Champlain, a capable explorer and geographer, at the time a lieutenant of Pierre du Gua de Monts, began a new settlement at Quebec, the first permanent settlement in Canada. Champlain was named the lieutenant general of Louis XIII in 1612, and in 1613, having renewed the quest for a route to the kingdom of China, he set out to explore the Ottawa River. As Cartier had done before him, he planted a number of crosses on his route. Some of them bore the royal arms of France, for instance, one on an island of Lac des Chats (Quebec), which he named Sainte-Croix Island, and one made of white cedar on the shore of Lac aux Allumettes (Province of Quebec). Champlain admonished the Amerindians to take good care of the crosses, some serving to mark his exploration route, others being more formal witnesses of his claim to the territory.[10]

In June 1671, Simon-François Daumont de Saint-Lusson gathered together fourteen First Nations tribes that had come from 100 leagues (some 400 kilometers) around the Jesuit mission at Sault-Ste-Marie. The interpreter, Nicolas Perrot, read a document in the native language claiming all the territories so far discovered and those to be discovered in the name of the King of France. A cross was raised, and beside it, a cedar post bearing the royal arms. A "sod of earth" was lifted in the air three times while the French and Amerindians shouted repeatedly "Long live the King". The assembly then chanted the Vexilla Regis (banners of the king) and the Exaudiat te Dominus (May the Lord hear you) which the Amerindians listened to in wonderment. Afterwards Father Allouez extolled the greatness and power of Louis XIV whose arms were displayed on the post and whom he described as the "Captain of the Greatest Captains". Daumont de Saint-Lusson then praised the sovereign, in "martial and eloquent language," and extended the protection of the king to the nations in attendance. In the evening, there were large bonfires, exchange of gifts, and a Te Deum (You God) was sung to thank God in the name of the First Nations, “… that they were now the subjects of so great and powerful a Monarch.”[11]

After attempts in Florida, the dream of a French north south empire was revived on a much stronger footing by the settlement of Louisiana. On 14 March 1682, René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle arrived at the village of the Arkansas Indians and, in the name of Louis XIV, took possession of the surrounding lands which he called Louisiana in honour of his king. The ceremony consisted of planting a column fashioned from a tree trunk on which was painted a cross bearing the royal arms of France. This ceremony was followed by native dances which marked the beginning of a three day feast. Further on, probably near the city now called Venice, at the mouth of the Mississippi River on the Gulf of Mexico, he again took possession of the territory during an impressive ceremony. He had the top of a hill cleared, put on a scarlet coat with gold trimmings, a large hat and a sword. A tree trunk floating in the river was squared and planted on the hill. The arms of the king were painted on the post, and an inscription engraved with a red-hot iron read: “Louis the Great, King of France and Navarre, reigns April 9, 1682.” Then the arms of the king were engraved on a sheet of copper cut out of a pot and were fixed to the post. Next, a large cross was erected while the Vexilla Regis and Te Deum were sung. This was followed by three musket salvos and cries of “Long live the King.” Finally La Salle harangued the crowd and took possession of the territory in the name of the king and his heirs. The new royal possessions were listed like an inventory which included geographic features and inhabitants: seas, harbours, ports, bays, adjacent straits, and all its nations, peoples, provinces, cities, towns, villages, mines, open-pit mines (minières), fisheries, and rivers.[12]

Louis-Joseph Gaultier de La Vérendrye, referred to as chevalier from 1736 onwards, was the fourth son of the explorer Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye. On 19 March 1743, he arrived with his men at the fort of the people he refers to as Gens de la Petite-Cerise in front of the present day Pierre, capital of South Dakota. On March 30, wanting to record his passage in the area, the Chevalier buried a lead tablet in the earth without telling his hosts. One side, no doubt prepared in a workshop since it is cleanly done, displays the royal arms of France within a triple circle and bears an inscription referring to the 26th year of the reign of Louis XV and to the Marquis Charles de Beauharnois, then Governor of New France. The date 1741 is clearly visible and the inscription goes on to inform us that Pierre Gaultier de La Vérendrye is the one placing the tablet. The reverse, which is crudely engraved with some kind of point, updates the information on the obverse. It clearly specifies that the tablet was placed there by the Chevalier de La Vérendrye on 30 March 1743. The plaque was found in 1913.[13]

In a report dated 10 October 1670, Talon states that he had requested everyone who claimed new land to display the royal arms of France and to prepare a written record of the claim, which would eventually serve to inform the sovereign.[14] Many land claiming ceremonies took place at the time of New France, but it is not always well recorded whether the arms of France were displayed or not. It is likely that the explorer, in many instances, did not have a durable material such as copper or lead on which to engrave the arms. The following are additional instances of land claiming ceremonies that involve the display of the royal arms of France. They are arranged chronologically and are gleaned from the Dictionary of Canadian Biography on line unless otherwise specified.

1583 - Étienne Bellenger takes possession of the area around the Bay of Fundy by attaching the arms of Cardinal de Bourbon to a tall tree, which possibly were discovered by Champlain in 1607.

1663 – The missionary Guillaume Couture plants a cross bearing the arms of the king in lower James Bay.[15]

1666 – Daniel Rémy de Courcelle plants a large cross and a post bearing the royal arms of France to claim Mohawk lands for Louis XIV.

1672 – Father Albanel buries a copper plate engraved with the royal arms at the foot of a large tree at James Bay and proclaims that the surrounding territories belong to France. On their way back, his companion, Denys de Saint-Simon, as instructed by Intendant Talon, plants the royal arms at Lake Nemiskau.[16]

1679 – Daniel Greysolon Dulhut winters at Sault Ste Marie and, in the summer, raises the arms of France in the land of the Nadouesioux. Similar ceremonies take place in strategic places of the Upper Great Lakes to serve notice on the English that these lands are now claimed by Louis XIV.

1693 - Claude-Sébastien de Villieu receives orders to post the king’s arms along a line separating New-France from New England.[17]

1732 - Joseph-Laurent Normandin marks the watershed separating the claims of England from those of France, north of Lake St. Jean, by means of fleurs-de-lis placed on trees.[18]

1749 - On reaching the Allegheny River on 15 June 1749, Pierre-Joseph Céloron de Blainville buries the first of a series of engraved lead plates claiming the land for France and attaches a plaque with the royal arms to a tree. At the end of August, he buries the last of his lead plates at the mouth of the Rivière à la Roche (Great Miami River).

4.2 Opposition to Land Claims

After Cartier had erected a cross at Gaspé Bay on 24 July 1534, chief Donnacona felt that he had been wronged and, when he approached Cartier’s ship in a canoe to protest, the French seized him and brought him on board along with those who were with him. Cartier feasted the chief and persuaded him to let his two sons, Domagaya and Taignoagny, sail away with him, promising to bring them back.

As we have seen, La Vérendrye secretly buried a lead plate in 1743, without telling his hosts. This surreptitious way of taking possession of a territory was in sharp contrast with the ostentatious and public fashion with which some other explorers proceeded, for instance, Daumont de Saint-Lusson and Cavelier de la Salle,

4.3 Royal Arms on other Occasions

An attempt at French colonization in North America was carried out on Sainte-Croix Island in 1604 by Pierre Du Gua de Monts who had been granted trade and settlement privilege by the king. The island not being large enough to sustain a permanent settlement, François Gravé, Sieur du Pont, the deputy of de Monts, and Samuel de Champlain moved the settlement to Port-Royal in 1605. This new settlement was the scene of an important heraldic event. On the 14 November 1606, Champlain and Jean de Biencourt de Poutrincourt, lieutenant-governor of Acadia, returned from a voyage of exploration which had brought them down to Cape Cod. To celebrate their return, a play called Le Théâtre de Neptune (The Theatre of Neptune) was staged in Annapolis Basin in front of the habitation at Port Royal. Above the gate, were installed the royal arms of France enclosed with a wreath of laurel. The arms must have been those of both France and Navarre since Marc Lescarbot, who describes this event, included a map in his History of New France displaying the two arms side by side. With the arms was the motto Duo protegit unus (One protects two), which may refer to the king protecting both France and Navarre. Underneath were the arms of de Monts with an inscription: Dabit Deus his quoque finem (God shall also give an end to these toils) from the Aeneid, book I.1.199. On the opposite side, the arms of de Poutrincourt were accompanied by the inscription Invia virtuti nulla est via (To valour no path is impassible) from Ovid, 14 Meiam 113.[19] These shields can be seen on the reconstructed gate: http://www.flickr.com/photos/kitonlove/3618044281/ (consulted 8 January 2014).

On 3 June, 1620, Jean Dobleau, superior of the Recollets, placed the first stone of their church, Notre-Dame-des-Anges, on which were engraved the arms of France and those of Henri de Bourbon, Prince of Condé, who had just been replaced as Viceroy of New France.[20] The practice of placing the arms of dignitaries on cornerstones of important buildings seemed habitual. On 6 May 1624, Champlain placed a stone in the foundation of his second habitation on which were engraved the arms of the king, those of Henry II, Duc of Montmorency, Viceroy of New France, as well as his own name and the date of the event.[21] The presence of Champlain’s name only seems a good indication that he did not possess arms, and no arms were ever uncovered for him.

A ceremony at which the arms of the king and of various dignitaries were displayed was the planting of the Maypole, originally a European tradition. The pole was ornamented with various decorations, religious symbols and arms. On the 1st of May 1637, soldiers erected such a pole in front of Fort Saint-Louis, the third fort of that name constructed in 1636 by Governor Charles Huault de Montmagny. The arms of the King Louis XIII, those of Cardinal Richelieu, the king’s chief minister, and those of Governor Montmagny were attached to the pole.[22]

In a letter of 29 October 1725, the military engineer, Joseph-Gaspard Chaussegros de Léry, informed the French Minister of Colonies that the arms of His Majesty had not been displayed in the colony as was proper. To remedy the situation, he had a number of them prepared by a sculptor and duly installed above the principal gates, buildings, forts and public places, namely at Château St. Louis (residence of the governor), the Palace (residence of the intendant), the stores, the barracks, Fort Chambly, as well as the guard-houses, prisons, and courts in Trois-Rivières and Montreal, so that the king’s sovereignty would be affirmed in his North American possessions.[23] The arms were also installed in churches and were later removed by the British.

The royal arms appeared on the seal of New France’s Conseil souverain, later named Conseil supérieur (fig. 3), and also on the reverse of coins widely circulated in New France, for instance: the écu which came in various denominations some of which continued to circulate after 1763, the douzain which was given a rating of 20 deniers when it appeared in the colony in 1662, the ½ and double sol shipped in large amounts to New France in 1720, as well as gold and silver Louis and the 5-sol and 15-sol pieces coined specifically for the North American colonies.[24] Although it is not known to what extent some coins circulated in New France, and in spite of the fact, that there was a chronic shortage of metallic money, coins probably remained the most important vehicle whereby the public came into contact with the sovereign’s shield: écu in French, the name given to one of the coins. On the Kebeca Liberata (Quebec delivered) medal struck to celebrate Count Frontenac’s victory over Admiral William Phips’ fleet before Quebec City in 1690, France is represented by a feminine allegorical figure, her left arm resting on a shield of the royal arms.[25] Officers’ gorgets were sometimes decorated in the centre with the royal coat of arms applied as a silver plate.[26] The arms of French sovereigns were also found on a large number of maps relating to North America to signify sovereignty over these territories.[27]

Fig. 3 Seal of the Conseil supérieur of New France, 1742. Library and Archives Canada, MG 18, H18, negative C – 103324.

The arms of the sovereigns were also used on a number of items connected with the Church. The Basilica-Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Québec has two liturgical vestments, a cope with the arms of France and Navarre and a richly embroidered chasuble with the same arms repeated below the crossbar, on both sides of a cross.[28] Another chasuble offered to the Parish of Saint-Charles-Borromée, Province of Quebec, is embroidered with the arms of Maria Theresa of Austria, spouse of Louis XIV. They display on a same shield, the royal arms of France on the left, alongside the arms of Habsburg Spain on the right.[29] Maria Theresa’s mother, Anne of Austria, who was also greatly appreciated for her faith and generosity to the Church, was honoured, on 13 August 1666, by an impressive service with many hatchments (arms displayed at funerals) and chapelle ardente (a chapel of rest for the deceased until the funeral service), in this case symbolically since her body was in France. The entry is as follows: “The 13th. A solemn service, with chapelle ardente and a great number of hatchments, etc., for the deceased Queen. Father Dablon pronounced the funeral oration, which gave great satisfaction.”[30] The royal arms also appeared on liturgical vessels such as a ciborium engraved with the arms of Louis XIV on the lid and foot, made at Rochefort in 1706 for Acadian missions.[31] A chalice and paten from Notre-Dame-de-l'Assomption parish in Beaubassin, bearing the royal arms on the foot of the chalice and rim of the paten, is held by the Musée acadien of the University of Moncton.[32] Three fleurs-de-lis arranged as in the royal arms are also found on church bells, one taken from the parish in Beaubassin and one dated 1666 which is said to have been offered to the chapel at Beauport by the seigneur Robert Giffard.[33] Many goods manufactured in France were marked with one or several fleurs-de-lis. An impressive bronze mortar made in France in 1636 displays six fleurs-de-lis, three on each side. It was found near Parry Sound (Ontario) in 1870 and is now held by the Canadian Museum of History.[34]

The arms of the Compagnie des Indes occidentales granted in 1664 are a blue field completely strewn with gold fleurs-de-lis, while in those granted to the Compagnie d'Occident in 1717, only the upper part (chief) is strewn with fleurs-de-lis. Arms promoted for Canada around 1715, but never granted, consist of a blue field peppered with gold fleurs-de-lis and the addition of a sun representing the Sun King, Louis XIV.[35]

4.4 French Flags

Fort Caroline erected in 1564 by the French Huguenots in what is now Jacksonville, Florida, displayed the banner of France as well as the royal arms, both featuring three gold fleurs-de-lis on a blue field.[36] The fort was destroyed the next year by the Spanish established at St. Augustine. The banner of France also flew from Pierre Du Gua de Monts’ quarters within the fort on Sainte-Croix Island in 1604.[37] This banner seems to have gone out of use with the death of Henry IV in 1610.[38] On the habitation Champlain built at Quebec in 1608, there was a mast above a sundial from which flew a dovetailed flag with fleurs-de-lis. What this flag was is not clear. It may have been a naval or military flag that Champlain had on hand and used to represent France.

Two other flags bore the royal arms on a white field. In 1664, article 27 of the edict creating the Compagnie des Indes occidentales authorized the company to fly the completely white flag of the French Royal Marine with the royal arms in centre.[39] On 3 December 1738, François Gaultier du Tremblay de La Vérendrye entered the main Mandan village in a region corresponding roughly to present-day North Dakota. He carried with him the same white flag with the royal arms.[40] The entirely white flag of the Royal Marine was at that time considered by Canadians as the flag of the French nation.[41]

5. English Tradition

5.1 Royal Emblems at Land Claims

When John Cabot (Giovanni Caboto) landed on the coast of North America on St. John the Baptist Day, 24 June 1497, he formally took possession of the surrounding territory in the name of King Henry VII of England. The letters patent from the king authorized him to sail under the royal flags, banners and ensigns and to take possession of any establishment or land under his banners and ensigns. During the land claiming ceremony, Cabot planted a large cross along with the Royal Standard (a banner of the king’s arms) and the banner of St. Mark.[42] The Royal Standard at the time consisted of the three gold fleurs-de-lis of France on blue and the three gold lions of England on red, both repeated twice. Since 1340, the fleurs-de-lis occupied the most important quarters of both the Royal Standard and royal arms to express England’s claim to the throne of France. Both banners raised by Cabot are illustrated on the following site: http://www.reformation.org/british-lion-venetian-lion.html (consulted 8 January 2014). Some historians have concluded that the flag Cabot raised was the banner of St. George with its red cross on white.[43] This is surely not a valid interpretation. The letters patent from the king clearly specified “our banner, flags and ensign” and the flag raised with the cross is designated as the bandera (bandièra) regia or royal banner.[44] It is also well documented that, at such ceremonies, the royal arms were usually displayed and the Royal Standard is essentially a banner of the royal arms. At that time, the red cross of St. George was a military flag and perhaps in the process of becoming a naval flag, but there is no reason to believe that it was closely connected with the sovereign.[45] Where Cabot landed exactly has been the object of much speculation. A Canadian landing is most likely, though a landing in Maine remains a possibility.[46] What is important here is that Cabot’s landing describes the first British land claiming ceremony in North America.

A rowboat used during Frobisher’s expedition to Baffin Island in 1577 carried the banner of St. George bearing in the centre the arms of Elizabeth I, which display the fleurs-de-lis and lion as did the Royal Standard raised by Cabot.[47] It is interesting that on a map in his 1615 journal, William Baffin marked his discovery route in search of the Northwest Passage with banners of St. George as well as with an ensign with multi-coloured horizontal stripes and the cross of St. George in canton. Both of these flags were likely also flown from his ship.[47a] On 5 August 1583, in St. John Harbour, Sir Humphrey Gilbert formally took possession of Newfoundland and the surrounding territory, 200 leagues (some 600 miles) to the north and south. This time, the witnesses at the ceremony were not members of the First Nations, but merchants and fishermen from 36 ships, Portuguese, Basque, French, and English in the harbour. The ceremony included presenting Gilbert with a rod representing authority and turf symbolizing the land. The laws and religion of England were proclaimed in the territory and a lead plate engraved with the arms of Queen Elizabeth I was attached to a pillar of wood.[48] In the spring of 1613, Sir Thomas Button who had wintered at the mouth of the Nelson River, planted a cross and a post to which were affixed the arms of England to take possession of the territory.[49] At Port Nelson in 1670, Charles Bayly went ashore, nailed the arms of Charles II engraved in brass to a tree, and laid claim to the territory.[50]

5.2 Removing Rival Emblems

In May 1613, Samuel Argall attacked Port Royal and after taking “everything that seemed convenient to him, even to the boards, bolts, locks and nails, set the place on fire.” They had “destroyed, everywhere, all monuments and evidences of the dominion of the French; and this they did not forget to do so here [Port Royal], even to making use of pick and chisel upon a large and massive stone, on which were cut the names of sieur de Monts and other Captains, with the fleurs-de-lys.” In July, the fort being built at Saint-Sauveur, on Mount Desert Island, now in Maine, received a similar treatment: “They burned our fortifications and tore down our Crosses, raising another to show they had taken possession of the country, and were the Masters thereof. … This Cross had carved upon it the name of the King of Great Britain.”[51] In 1632, Andrew Forrester sacked the French fort on the Saint-John River and destroyed a large wooden cross bearing the arms of France.[52]

When Quebec City was captured on 16 September 1759, two shields were taken from the city gates by James Murray, who was to become Governor of Canada, and by Vice-Admiral Charles Saunders, commander of the fleet which carried Wolfe's troops to Canada. James Murray presented his shield to the city of Hastings, of which he was a jurat. Saunders presented his to the Royal Naval College of Portsmouth where it was placed on a special panel in one of the rooms of the College's dockyard. Below the shield, was a panoply in centre of which a cartouche bore the inscription:

“This trophy was taken down from the gates of Quebec when that place was conquered on the 18th of Sept., 1759 by the Perseverance and Conduct of VICE-ADMIRAL SAUNDERS and BRIGADIER-GENERAL WOLFE, seconded by the Bravery and continued ardour OF THE FLEET AND ARMY, under their respective Commands.”

The shield at Portsmouth was returned to Canada in 1917 at the request of Sir Arthur Doughty, Dominion Archivist, and with the strong support of Lord Grey, then governor general of Canada, and Lord Jellicoe, First Sea Lord and Chief of Naval staff of Britain, who was a good friend of Doughty (fig. 4). In 1920, Quebec City began investigating the possibility of having the Hastings shield returned. Based on the Portsmouth precedent and with strong support from the High Commissioner of Canada in London, M. P. C. Larkin, and the governor general of Canada, Lord Willington, a former Member of Parliament for Hastings, the City was successful in its quest. The shield was returned to the City of Quebec during an official ceremony in 1925.[53]

The arms of the Compagnie des Indes occidentales granted in 1664 are a blue field completely strewn with gold fleurs-de-lis, while in those granted to the Compagnie d'Occident in 1717, only the upper part (chief) is strewn with fleurs-de-lis. Arms promoted for Canada around 1715, but never granted, consist of a blue field peppered with gold fleurs-de-lis and the addition of a sun representing the Sun King, Louis XIV.[35]

4.4 French Flags

Fort Caroline erected in 1564 by the French Huguenots in what is now Jacksonville, Florida, displayed the banner of France as well as the royal arms, both featuring three gold fleurs-de-lis on a blue field.[36] The fort was destroyed the next year by the Spanish established at St. Augustine. The banner of France also flew from Pierre Du Gua de Monts’ quarters within the fort on Sainte-Croix Island in 1604.[37] This banner seems to have gone out of use with the death of Henry IV in 1610.[38] On the habitation Champlain built at Quebec in 1608, there was a mast above a sundial from which flew a dovetailed flag with fleurs-de-lis. What this flag was is not clear. It may have been a naval or military flag that Champlain had on hand and used to represent France.

Two other flags bore the royal arms on a white field. In 1664, article 27 of the edict creating the Compagnie des Indes occidentales authorized the company to fly the completely white flag of the French Royal Marine with the royal arms in centre.[39] On 3 December 1738, François Gaultier du Tremblay de La Vérendrye entered the main Mandan village in a region corresponding roughly to present-day North Dakota. He carried with him the same white flag with the royal arms.[40] The entirely white flag of the Royal Marine was at that time considered by Canadians as the flag of the French nation.[41]

5. English Tradition

5.1 Royal Emblems at Land Claims

When John Cabot (Giovanni Caboto) landed on the coast of North America on St. John the Baptist Day, 24 June 1497, he formally took possession of the surrounding territory in the name of King Henry VII of England. The letters patent from the king authorized him to sail under the royal flags, banners and ensigns and to take possession of any establishment or land under his banners and ensigns. During the land claiming ceremony, Cabot planted a large cross along with the Royal Standard (a banner of the king’s arms) and the banner of St. Mark.[42] The Royal Standard at the time consisted of the three gold fleurs-de-lis of France on blue and the three gold lions of England on red, both repeated twice. Since 1340, the fleurs-de-lis occupied the most important quarters of both the Royal Standard and royal arms to express England’s claim to the throne of France. Both banners raised by Cabot are illustrated on the following site: http://www.reformation.org/british-lion-venetian-lion.html (consulted 8 January 2014). Some historians have concluded that the flag Cabot raised was the banner of St. George with its red cross on white.[43] This is surely not a valid interpretation. The letters patent from the king clearly specified “our banner, flags and ensign” and the flag raised with the cross is designated as the bandera (bandièra) regia or royal banner.[44] It is also well documented that, at such ceremonies, the royal arms were usually displayed and the Royal Standard is essentially a banner of the royal arms. At that time, the red cross of St. George was a military flag and perhaps in the process of becoming a naval flag, but there is no reason to believe that it was closely connected with the sovereign.[45] Where Cabot landed exactly has been the object of much speculation. A Canadian landing is most likely, though a landing in Maine remains a possibility.[46] What is important here is that Cabot’s landing describes the first British land claiming ceremony in North America.

A rowboat used during Frobisher’s expedition to Baffin Island in 1577 carried the banner of St. George bearing in the centre the arms of Elizabeth I, which display the fleurs-de-lis and lion as did the Royal Standard raised by Cabot.[47] It is interesting that on a map in his 1615 journal, William Baffin marked his discovery route in search of the Northwest Passage with banners of St. George as well as with an ensign with multi-coloured horizontal stripes and the cross of St. George in canton. Both of these flags were likely also flown from his ship.[47a] On 5 August 1583, in St. John Harbour, Sir Humphrey Gilbert formally took possession of Newfoundland and the surrounding territory, 200 leagues (some 600 miles) to the north and south. This time, the witnesses at the ceremony were not members of the First Nations, but merchants and fishermen from 36 ships, Portuguese, Basque, French, and English in the harbour. The ceremony included presenting Gilbert with a rod representing authority and turf symbolizing the land. The laws and religion of England were proclaimed in the territory and a lead plate engraved with the arms of Queen Elizabeth I was attached to a pillar of wood.[48] In the spring of 1613, Sir Thomas Button who had wintered at the mouth of the Nelson River, planted a cross and a post to which were affixed the arms of England to take possession of the territory.[49] At Port Nelson in 1670, Charles Bayly went ashore, nailed the arms of Charles II engraved in brass to a tree, and laid claim to the territory.[50]

5.2 Removing Rival Emblems

In May 1613, Samuel Argall attacked Port Royal and after taking “everything that seemed convenient to him, even to the boards, bolts, locks and nails, set the place on fire.” They had “destroyed, everywhere, all monuments and evidences of the dominion of the French; and this they did not forget to do so here [Port Royal], even to making use of pick and chisel upon a large and massive stone, on which were cut the names of sieur de Monts and other Captains, with the fleurs-de-lys.” In July, the fort being built at Saint-Sauveur, on Mount Desert Island, now in Maine, received a similar treatment: “They burned our fortifications and tore down our Crosses, raising another to show they had taken possession of the country, and were the Masters thereof. … This Cross had carved upon it the name of the King of Great Britain.”[51] In 1632, Andrew Forrester sacked the French fort on the Saint-John River and destroyed a large wooden cross bearing the arms of France.[52]

When Quebec City was captured on 16 September 1759, two shields were taken from the city gates by James Murray, who was to become Governor of Canada, and by Vice-Admiral Charles Saunders, commander of the fleet which carried Wolfe's troops to Canada. James Murray presented his shield to the city of Hastings, of which he was a jurat. Saunders presented his to the Royal Naval College of Portsmouth where it was placed on a special panel in one of the rooms of the College's dockyard. Below the shield, was a panoply in centre of which a cartouche bore the inscription:

“This trophy was taken down from the gates of Quebec when that place was conquered on the 18th of Sept., 1759 by the Perseverance and Conduct of VICE-ADMIRAL SAUNDERS and BRIGADIER-GENERAL WOLFE, seconded by the Bravery and continued ardour OF THE FLEET AND ARMY, under their respective Commands.”

The shield at Portsmouth was returned to Canada in 1917 at the request of Sir Arthur Doughty, Dominion Archivist, and with the strong support of Lord Grey, then governor general of Canada, and Lord Jellicoe, First Sea Lord and Chief of Naval staff of Britain, who was a good friend of Doughty (fig. 4). In 1920, Quebec City began investigating the possibility of having the Hastings shield returned. Based on the Portsmouth precedent and with strong support from the High Commissioner of Canada in London, M. P. C. Larkin, and the governor general of Canada, Lord Willington, a former Member of Parliament for Hastings, the City was successful in its quest. The shield was returned to the City of Quebec during an official ceremony in 1925.[53]

Fig. 4 Trophy taken from the gates of Quebec City in 1759. Given to the Royal Naval College of Portsmouth by Vice-Admiral Charles Saunders. Returned to Canada in 1917. Now held by the Canadian War Museum.

In 1775, Guy Carleton, Governor General of Canada, received instructions from London “… that Our Arms [King George III] and Insignia be put up not only in all … Churches and Places of holy Worship, but also in all Courts of Justice; and that the Arms of France be taken down in every such Church or Court, where they may at present remain.” Perhaps this was not done too diligently since Governor Carlton, then Lord Dorchester, received the same instructions in 1791.[54]

5.3 The Royal Arms of the United Kingdom on other Occasions

The royal arms, as well as the effigy of Britannia holding a shield bearing the Union Flag, appeared on a number of coins circulated in Canada.[55] The arms were also featured on the provincial seals prior to Confederation and sometimes after, on the Great Seals of Canada from Queen Victoria to King George V (fig. 5), as well as on some of the Great Seals of British sovereigns used in connection with Canada. The royal arms as borne from 1801 to 1806 appear under the arches of the crown which tops Canada’s Senate mace. They adorn a number of documents such as royal proclamations relating to Canada and grants of arms to Canadian citizens or corporations by the Kings of Arms of England.

5.3 The Royal Arms of the United Kingdom on other Occasions

The royal arms, as well as the effigy of Britannia holding a shield bearing the Union Flag, appeared on a number of coins circulated in Canada.[55] The arms were also featured on the provincial seals prior to Confederation and sometimes after, on the Great Seals of Canada from Queen Victoria to King George V (fig. 5), as well as on some of the Great Seals of British sovereigns used in connection with Canada. The royal arms as borne from 1801 to 1806 appear under the arches of the crown which tops Canada’s Senate mace. They adorn a number of documents such as royal proclamations relating to Canada and grants of arms to Canadian citizens or corporations by the Kings of Arms of England.

Fig. 5 Great Seal of the Province of Canada, following the union of Upper and Lower Canada in 1840. Two allegorical figures hold the former seals of Upper Canada (right) and of Lower Canada (left). The arms of Queen Victoria are at the top. Reproduced on a pin dish created by Doulton & Co. (England) in 1967. A. & P. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

The royal emblem was often used in connection with churches because the sovereign is the temporal head of the Anglican Church. A first important royal gift was a communion set given by Queen Anne to the Mohawks in 1711. The three items of the set, a footed paten, a chalice and a flagon are all engraved with the arms of the queen and her cypher. These treasures are housed in Christ Church, Her Majesty's Chapel of the Mohawks near Deseronto, Ontario, which is administered by the Anglican Parish of Tyendinaga. In 1984, to mark the bicentennial of the coming of the United Empire Loyalists to Ontario, including the Mohawks, Queen Elizabeth II donated the chapel a communion chalice displaying her royal arms of Canada. The original wood carving of the royal arms given to the church by George III in 1798 were destroyed by fire in 1905 and replaced by a replica offered by King George V. St. Paul's Anglican Church, Halifax, received a communion set commissioned by Queen Anne and presented by King George I around 1720. It displays the arms of the queen, but the royal cypher was re-engraved to GR rather than AR. The set came to St. Paul’s from Annapolis Royal in 1759 on the order of Governor Lawrence. The governor’s pew in the church was ornamented with the arms of King George III in 1786.

In Newfoundland, the arms of George III, circa 1786, are found in St. Luke’s Anglican Church, Placentia and in St. Thomas' Anglican Church, also called Old Garrison Church, opened in 1836 in St. John’s. The arms of Queen Victoria are displayed above the door of St. Luke’s Anglican Church in Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia, and the royal arms as they existed from 1714 to 1801 can be seen over the west door of Trinity Church, St. John, New Brunswick. Christ Church in Sorel possesses an oil painting of the royal arms which are said to have been sent from England to hang over the pew of Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, son of George III, who was appointed General and Commander-in-Chief of the Forces in North America in 1799. These arms still exist and hang in the present church as a valued possession from earlier days, but the connection with the Duke of Kent is not clear. He does not seem to have been present at Sorel long enough to qualify as a resident.[56]

In 1790, at the founding of the Parish of Christ Church in Windsor, Nova Scotia, George III, through the Archbishop of Canterbury, presented the parish with silver flagons, a paten, two chalices and a collection of plates engraved with the royal arms. The set is still used for special ceremonies. Holy Trinity Anglican Church (Bishop Stewart Memorial Church) in

Frelighsburg, Quebec, has a silver flagon and footed paten both adorned with the arms and cypher of George III. One of the finest gifts of altar vessels was made by George III to The Holy Trinity Anglican Cathedral of Quebec City in1804. It consists of twelve pieces of solid silver all embossed with the royal arms and the arms of the diocese. The viceregal pew in St. Bartholomew's Anglican Church, Ottawa, built in 1868, is decorated with the royal arms. The bells of Notre Dame Cathedral in Montreal, cast by Thomas Mears of Whitechapel Foundery, London in 1843, are marked with the royal arms of Queen Victoria.[57]

As can be expected the royal arms also adorn stained glass windows in churches. Examples of the arms as used from Queen Victoria’s time are found in a window representing Queen Anne receiving the four Indian Kings at Court in 1710 in Her Majesty’s Chapel of the Mohawks near Deseronto, and in King George V Silver Jubilee window in St. James Cathedral in Toronto. In St. James also, the Victoria arms are seen below a clock in front of the organ balcony.

The royal arms of the United Kingdom are displayed in the British Columbia courts as well as in the Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador. They were used in other provinces and, because of their historical importance, some of these arms have been preserved, even after Canada had its own royal arms and had become an independent country in 1931. The royal arms of George IV are seen on a panel between two allegorical figures, one representing law, the other justice, behind the justice’s bench in the Appeal Court of New Brunswick in Fredericton. In the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal, located in the Law Courts Building in Halifax, the arms of the sovereign, as they exist since the time of Victoria, are displayed above the justice’s bench in the sixth-floor courtroom. The same arms are present over the dais of the Court of Appeal for Ontario at Osgoode Hall and adorn the tympanum of the portico of Charlotte County Court House in St. Andrews, New Brunswick.

The idea of the royal mail was given expression by the royal arms on Canadian Post Offices. The arms of Queen Victoria, carved in stone, still appear above the portico of Toronto’s seventh Post Office built in 1851-53 on Toronto Street. Some letterboxes bearing the royal arms are now kept in various collections.[58]

The royal emblem was also displayed during royal visits to Canada. When George VI visited Canada in 1939, his arms were placed under the headlights of C.N.R. locomotive #6047. The royal arms are also seen on government buildings, for instance; above the main entrance to Rideau Hall, in many provincial parliament buildings, on the façade of the Royal Mint in Ottawa, above the main entrance to the Meteorological building erected as an observatory by the Canadian Government and now the Admissions and Awards Office of the University of Toronto, and over the entrance portico of the Dominion Astrophysical Observatory in Victoria (British Columbia). A lion holds the royal arms in front of the Peace Tower of the Parliament building and inside, over doors of the House of Commons, the arms accompany the heads of Henry VII (reigned 1485-1509) and François I (reigned 1515-1547), two kings who presided over the early discoveries in North America. The arms of France and Navarre accompany one set of heads, while two versions of the royal arms of England accompany the other set. Ironically, François I’s titles did not include Navarre, nor did he place the arms of that kingdom along those of France. Also the arms of England are not of the times when the two kings reigned. The shield on the right is of the periods 1603-1688 and 1702-1707, and the shield on the left was in use from 1714 to 1801.

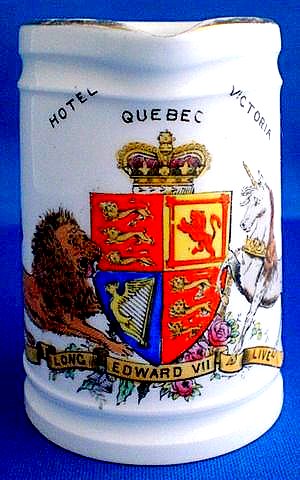

The armorial bearings of British sovereigns also occurred in many other places often in connection with royalty, but also on souvenirs sold in Canada and sometimes in connection with commercial enterprises (figs 6-9).

In Newfoundland, the arms of George III, circa 1786, are found in St. Luke’s Anglican Church, Placentia and in St. Thomas' Anglican Church, also called Old Garrison Church, opened in 1836 in St. John’s. The arms of Queen Victoria are displayed above the door of St. Luke’s Anglican Church in Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia, and the royal arms as they existed from 1714 to 1801 can be seen over the west door of Trinity Church, St. John, New Brunswick. Christ Church in Sorel possesses an oil painting of the royal arms which are said to have been sent from England to hang over the pew of Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, son of George III, who was appointed General and Commander-in-Chief of the Forces in North America in 1799. These arms still exist and hang in the present church as a valued possession from earlier days, but the connection with the Duke of Kent is not clear. He does not seem to have been present at Sorel long enough to qualify as a resident.[56]

In 1790, at the founding of the Parish of Christ Church in Windsor, Nova Scotia, George III, through the Archbishop of Canterbury, presented the parish with silver flagons, a paten, two chalices and a collection of plates engraved with the royal arms. The set is still used for special ceremonies. Holy Trinity Anglican Church (Bishop Stewart Memorial Church) in

Frelighsburg, Quebec, has a silver flagon and footed paten both adorned with the arms and cypher of George III. One of the finest gifts of altar vessels was made by George III to The Holy Trinity Anglican Cathedral of Quebec City in1804. It consists of twelve pieces of solid silver all embossed with the royal arms and the arms of the diocese. The viceregal pew in St. Bartholomew's Anglican Church, Ottawa, built in 1868, is decorated with the royal arms. The bells of Notre Dame Cathedral in Montreal, cast by Thomas Mears of Whitechapel Foundery, London in 1843, are marked with the royal arms of Queen Victoria.[57]

As can be expected the royal arms also adorn stained glass windows in churches. Examples of the arms as used from Queen Victoria’s time are found in a window representing Queen Anne receiving the four Indian Kings at Court in 1710 in Her Majesty’s Chapel of the Mohawks near Deseronto, and in King George V Silver Jubilee window in St. James Cathedral in Toronto. In St. James also, the Victoria arms are seen below a clock in front of the organ balcony.

The royal arms of the United Kingdom are displayed in the British Columbia courts as well as in the Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador. They were used in other provinces and, because of their historical importance, some of these arms have been preserved, even after Canada had its own royal arms and had become an independent country in 1931. The royal arms of George IV are seen on a panel between two allegorical figures, one representing law, the other justice, behind the justice’s bench in the Appeal Court of New Brunswick in Fredericton. In the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal, located in the Law Courts Building in Halifax, the arms of the sovereign, as they exist since the time of Victoria, are displayed above the justice’s bench in the sixth-floor courtroom. The same arms are present over the dais of the Court of Appeal for Ontario at Osgoode Hall and adorn the tympanum of the portico of Charlotte County Court House in St. Andrews, New Brunswick.

The idea of the royal mail was given expression by the royal arms on Canadian Post Offices. The arms of Queen Victoria, carved in stone, still appear above the portico of Toronto’s seventh Post Office built in 1851-53 on Toronto Street. Some letterboxes bearing the royal arms are now kept in various collections.[58]

The royal emblem was also displayed during royal visits to Canada. When George VI visited Canada in 1939, his arms were placed under the headlights of C.N.R. locomotive #6047. The royal arms are also seen on government buildings, for instance; above the main entrance to Rideau Hall, in many provincial parliament buildings, on the façade of the Royal Mint in Ottawa, above the main entrance to the Meteorological building erected as an observatory by the Canadian Government and now the Admissions and Awards Office of the University of Toronto, and over the entrance portico of the Dominion Astrophysical Observatory in Victoria (British Columbia). A lion holds the royal arms in front of the Peace Tower of the Parliament building and inside, over doors of the House of Commons, the arms accompany the heads of Henry VII (reigned 1485-1509) and François I (reigned 1515-1547), two kings who presided over the early discoveries in North America. The arms of France and Navarre accompany one set of heads, while two versions of the royal arms of England accompany the other set. Ironically, François I’s titles did not include Navarre, nor did he place the arms of that kingdom along those of France. Also the arms of England are not of the times when the two kings reigned. The shield on the right is of the periods 1603-1688 and 1702-1707, and the shield on the left was in use from 1714 to 1801.

The armorial bearings of British sovereigns also occurred in many other places often in connection with royalty, but also on souvenirs sold in Canada and sometimes in connection with commercial enterprises (figs 6-9).

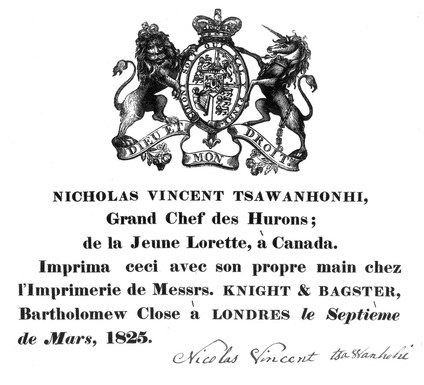

Fig. 6 This little handbill features the arms of King George IV along with an inscription informing us that Nicolas Vincent Tsawanhonhi (Tsaouenhohoui), grand chief of the Hurons of Jeune-Lorette (Wendake, Quebec), printed this creation with his own hand at Knight & Bagster, printers in Bartholomew Close, London, 7 March 1825. It is signed by the grand chief. Library and Archives Canada, negative C – 111475.

Fig. 7 Royal arms on a creamer of Hotel Victoria, Quebec City, c. 1901, by The Foley China (Wileman & Co), England. A. & P. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

Fig. 8 Prince Arthur William Patrick Albert, Duke of Connaught and of Strathearn, Governor General of Canada, 1911-16, bore the royal arms differenced with the smaller shield of Saxony in centre and a specific label (looks like a three-footed bench) at the top of the shield and on the lion in the crest. Around the shield is the collar of the Most Noble Order of the Garter.

Fig. 9 Royal arms on a souvenir plate of Montreal, 1911, by Wedgwood, England. Similar plates were created for cities across Canada. A. & P. Vachon Collection, Canadian Museum of History.

5.4 The Union Flag (Union Jack)

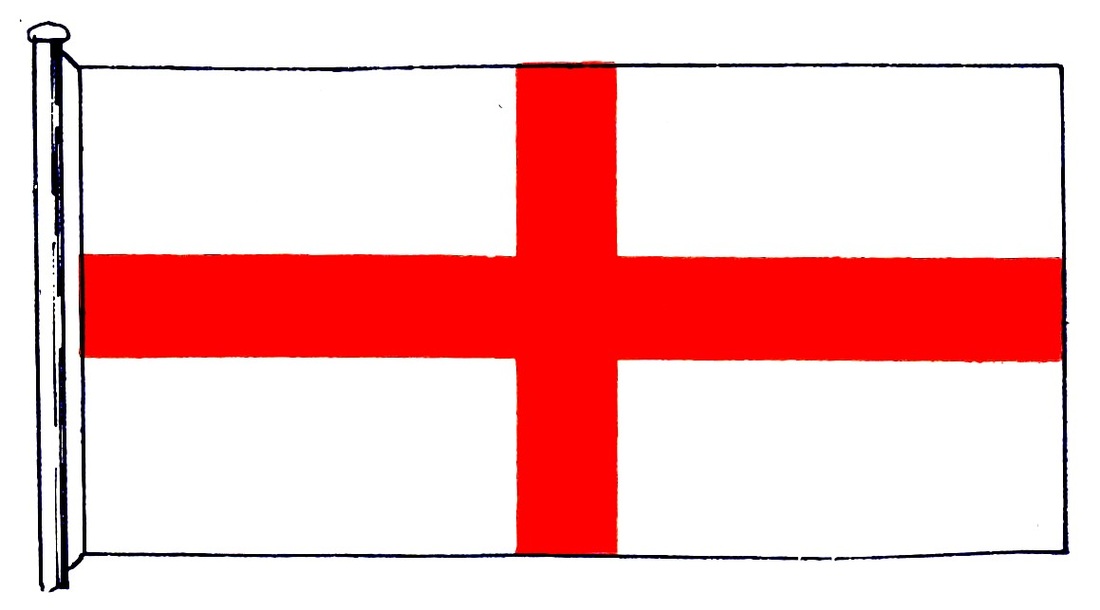

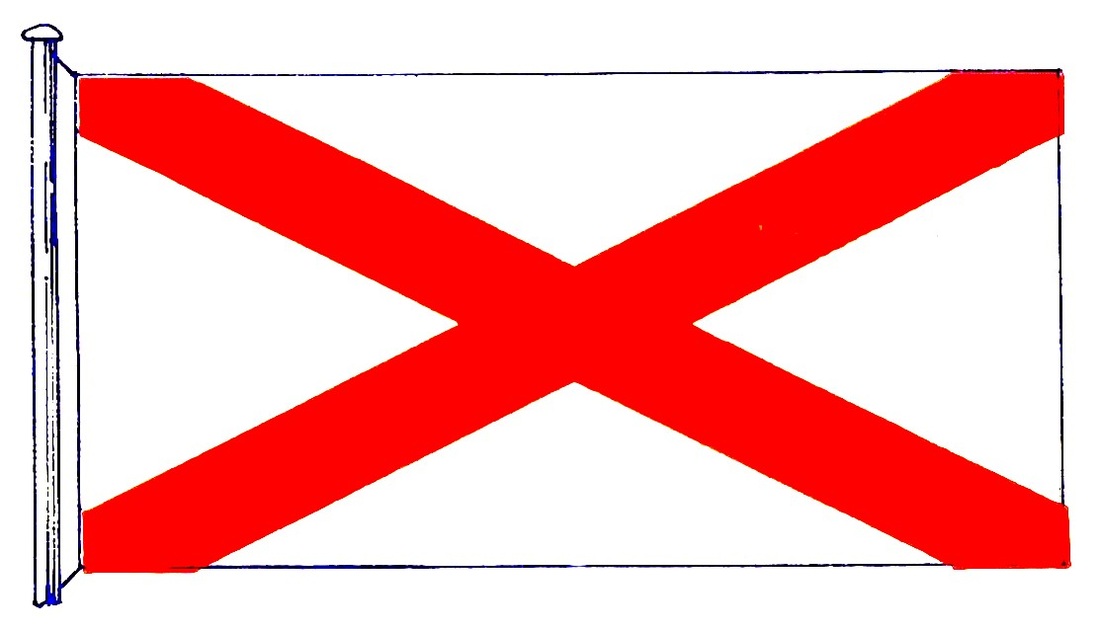

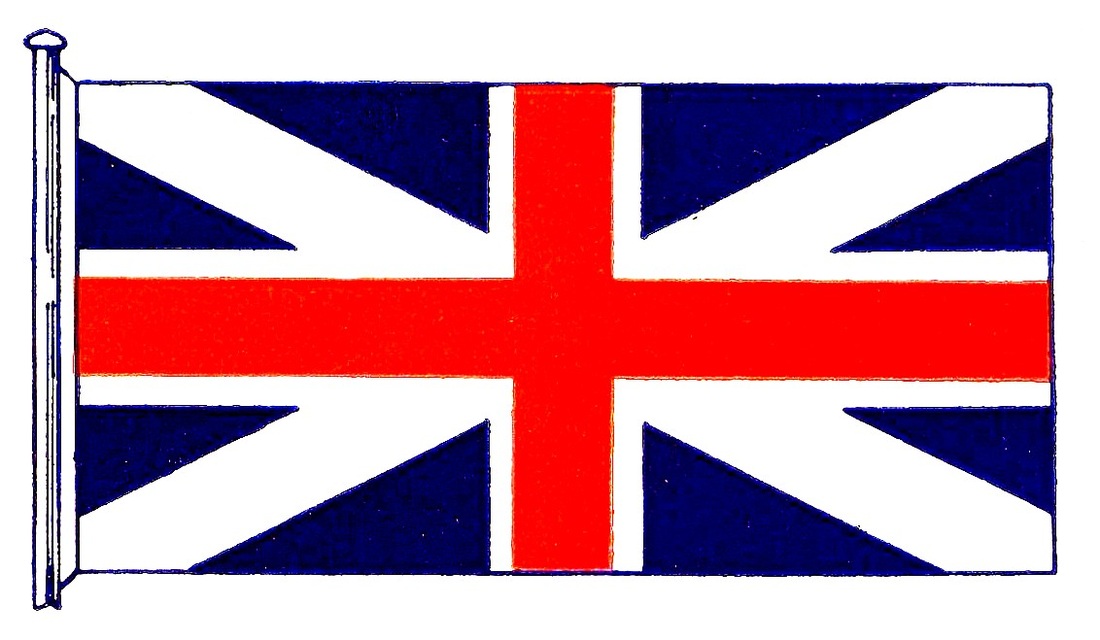

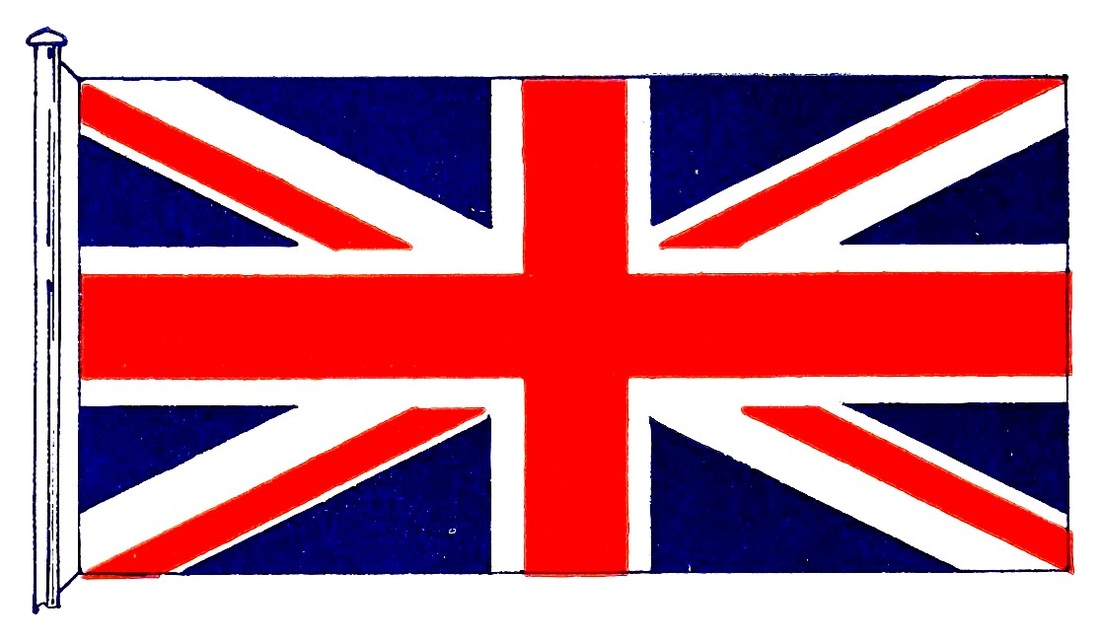

The use of the banner of St. George by English kings is recorded in the second half of the thirteenth century. In the last quarter of the fourteenth century, the banner represented England both on the battlefield and on the sea.[59] The flag with the cross of St. George and the saltire of St. Andrew came into being in 1606 after the crowns of England and Scotland were united. It was replaced by another type of Jack during the period of the Cromwells, but was brought back in 1660 with the restoration of Charles II and kept following the union of England and Scotland to create the United Kingdom in 1707. When Ireland joined the United Kingdom in 1801, the saltire of St. Patrick was added to the other two crosses (figs. 10-15).

The use of the banner of St. George by English kings is recorded in the second half of the thirteenth century. In the last quarter of the fourteenth century, the banner represented England both on the battlefield and on the sea.[59] The flag with the cross of St. George and the saltire of St. Andrew came into being in 1606 after the crowns of England and Scotland were united. It was replaced by another type of Jack during the period of the Cromwells, but was brought back in 1660 with the restoration of Charles II and kept following the union of England and Scotland to create the United Kingdom in 1707. When Ireland joined the United Kingdom in 1801, the saltire of St. Patrick was added to the other two crosses (figs. 10-15).

A view of Montreal in Canada, Taken from Isle St. Helena in 1762 by Thomas Davies shows the Union Jack flying within the fortifications of the city. [60] The use of this flag on forts is also recorded very early, for instance; we find the two-cross flag in the engraving entitled A north-east view of Prince of Wales’s Fort in Hudson’s, Bay North America by Samuel Hearne, 1777.[61] On the other hand, A South West View of Prince of Wales's Fort, Hudson’s Bay dated 1797, shows the St. George cross only.[62] This may seem like an aberration, but it is recorded that on the English forts of West Africa, in Gambia, Sierra Leone, and Cape Coast, governors and generals had permission to fly the Union Jack, whereas lesser officers were allowed to fly the cross of St. George.[63] Although we do not know on what authority this was allowed, it might explain the cross of St. George on Fort Prince of Wales, since there tended to be some uniformity throughout the empire.

The two-cross Union Flag or Jack flies from Fort York (York Factory) taken in 1782 by Jean-François Galaup, Count of La Pérouse.[64] The same flag flies from the blockhouses of Fort Lawrence, near present day Amherst, Nova Scotia, as seen in a 1755 drawing by Captain J. Hamilton.[65] In a watercolour of the interior of Fort York in 1804, a large two-cross Union Flag is flying from a mast near a blockhouse.[66] The three-cross Union Flag flies from a mast in the middle of Colonel Wolseley’s camp at Prince Arthur Landing on Lake Superior, Ontario, in 1870. The troops are on their way to the Red River in Manitoba.[67]

The rivalry between the Red Ensign and Union Flag that existed on forts continued on government buildings. This will be dealt with in chapter III.

5.5 The Red Ensign

From 1620 to 1707, the Red Ensign displayed only the red cross of St. George in canton. In1707, the white saltire of St. Andrew was added, and in 1801, the red saltire of St. Patrick joined the other two.[68] Though there seems to be no document granting such an authorization, the Red Ensign, which is the flag of the British Merchant Marine, was flown from forts in Canada, much in the same way that the white flag of French Royal Marine was flown from the forts of New France. A very early example of this use can be seen on an engraving showing the capture of Fort Nelson by Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville in 1697. From one of the fort’s towers flies the Red Ensign with the single cross of St. George in the upper corner adjacent to the staff.[69] The rather indiscriminate use of flags leads one to believe that the keepers of forts sometimes flew whatever they had on hand. For instance, a watercolour by James Hunter dated 1779 shows the Blue Ensign flying from Fort Saint John on the Richelieu River, while another by James Peachey dated 1783 shows the Red Ensign flying from Fort Cataraqui.[70]

We know from the watercolours of Peter Rindisbacher that the flying of the Red Ensign over Hudson’s Bay Company forts had become widespread by 1821, but when did the company begin placing the letters HBC in the fly?[71] In the eighteenth century, the Hudson’s Bay placed these letters on flags of various colours, but what was the exact purpose of these flags remains a mystery.[72] The placement of the letters HBC in the fly of the Red Ensign is clearly recorded for the year 1845, although the practice could have existed long before that date.[73] In the second half of the nineteenth century, this pattern is well established as can be seen in a watercolour of Fort William (Thunder Bay, Ontario) in 1878 and an interior view of Fort Garry (Winnipeg, Manitoba) in the 1880s.[74] In the case of the North West Company, the Red Ensign with the monogram N. W. Co. was already present at its post on Charlton Island in James Bay in 1804.[75]

Besides its use on forts, the Red Ensign was flown on land to mark Canada’s links with Great Britain. This was done both before and following Confederation.[76] A royal warrant of Queen Victoria granted arms to the provinces of Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in 1868. The warrant further authorized that these four arms quartered on one shield should serve as a common seal for the newly confederated provinces. The quartered arms were viewed as being those of Canada and served to create a canadianized version of the Red Ensign, at first spontaneously, then officially. The quartered shield also appeared on the Union Jack to provide a distinctive flag for the governor general. These matters are dealt with in detail in chapter III.

***

The object of this chapter is not to include every instance where the emblems of France or the United Kingdom were used in Canada. Its purpose is rather to show that the display of the emblems of these two countries goes back to the days of discovery and settlement of Canada and constitute an essential part of the country’s European heraldic heritage. Though these emblems were here at a time of intense rivalry between two European powers, they are today well represented in the arms granted to Canada in 1921.

The two-cross Union Flag or Jack flies from Fort York (York Factory) taken in 1782 by Jean-François Galaup, Count of La Pérouse.[64] The same flag flies from the blockhouses of Fort Lawrence, near present day Amherst, Nova Scotia, as seen in a 1755 drawing by Captain J. Hamilton.[65] In a watercolour of the interior of Fort York in 1804, a large two-cross Union Flag is flying from a mast near a blockhouse.[66] The three-cross Union Flag flies from a mast in the middle of Colonel Wolseley’s camp at Prince Arthur Landing on Lake Superior, Ontario, in 1870. The troops are on their way to the Red River in Manitoba.[67]

The rivalry between the Red Ensign and Union Flag that existed on forts continued on government buildings. This will be dealt with in chapter III.

5.5 The Red Ensign

From 1620 to 1707, the Red Ensign displayed only the red cross of St. George in canton. In1707, the white saltire of St. Andrew was added, and in 1801, the red saltire of St. Patrick joined the other two.[68] Though there seems to be no document granting such an authorization, the Red Ensign, which is the flag of the British Merchant Marine, was flown from forts in Canada, much in the same way that the white flag of French Royal Marine was flown from the forts of New France. A very early example of this use can be seen on an engraving showing the capture of Fort Nelson by Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville in 1697. From one of the fort’s towers flies the Red Ensign with the single cross of St. George in the upper corner adjacent to the staff.[69] The rather indiscriminate use of flags leads one to believe that the keepers of forts sometimes flew whatever they had on hand. For instance, a watercolour by James Hunter dated 1779 shows the Blue Ensign flying from Fort Saint John on the Richelieu River, while another by James Peachey dated 1783 shows the Red Ensign flying from Fort Cataraqui.[70]

We know from the watercolours of Peter Rindisbacher that the flying of the Red Ensign over Hudson’s Bay Company forts had become widespread by 1821, but when did the company begin placing the letters HBC in the fly?[71] In the eighteenth century, the Hudson’s Bay placed these letters on flags of various colours, but what was the exact purpose of these flags remains a mystery.[72] The placement of the letters HBC in the fly of the Red Ensign is clearly recorded for the year 1845, although the practice could have existed long before that date.[73] In the second half of the nineteenth century, this pattern is well established as can be seen in a watercolour of Fort William (Thunder Bay, Ontario) in 1878 and an interior view of Fort Garry (Winnipeg, Manitoba) in the 1880s.[74] In the case of the North West Company, the Red Ensign with the monogram N. W. Co. was already present at its post on Charlton Island in James Bay in 1804.[75]

Besides its use on forts, the Red Ensign was flown on land to mark Canada’s links with Great Britain. This was done both before and following Confederation.[76] A royal warrant of Queen Victoria granted arms to the provinces of Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in 1868. The warrant further authorized that these four arms quartered on one shield should serve as a common seal for the newly confederated provinces. The quartered arms were viewed as being those of Canada and served to create a canadianized version of the Red Ensign, at first spontaneously, then officially. The quartered shield also appeared on the Union Jack to provide a distinctive flag for the governor general. These matters are dealt with in detail in chapter III.

***

The object of this chapter is not to include every instance where the emblems of France or the United Kingdom were used in Canada. Its purpose is rather to show that the display of the emblems of these two countries goes back to the days of discovery and settlement of Canada and constitute an essential part of the country’s European heraldic heritage. Though these emblems were here at a time of intense rivalry between two European powers, they are today well represented in the arms granted to Canada in 1921.

NOTES

[1] Reuben Gold Thwaites, New Voyages to North America by Baron de Lahontan, vol. 2 (Chicago: A. C. McClurg &Co., 1905), p. 510.

[2] Sir Anthony Wagner, Heralds and Ancestors (London: British Museum, 1978), p. 7.

[3] Stephen Friar, A New Dictionary of Heraldry (London: A & C Black, 1987), pp. 330-33; G. Eysenbach, Histoire du blason et science des armoiries (Tours: Ad Mame, 1848), p. 176.

[4] For further information, see George MacBeath, “The Atlantic Region” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1966), pp. 21-26; Thomas Aubert’s biography in Dictionary of Canadian Biography online: http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/aubert_thomas_1E.html, consulted 23 January 2014.

[5] H.P. Biggar, The Voyages of Jacques Cartier (Ottawa: F.A. Acland, 1924), p. 64.

[6] Ibid., p. 225.

[7] Cartier’s biography in Dictionary of Canadian Biography online: http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cartier_jacques_1491_1557_1E.html, consulted 8 Jan. 2014.

[8] John Goss, The Mapping of North America, Three centuries of map-making 1500-1860, (Secaucus [New Jersey]: Wellfleet Press, 1990), pp. 34-35.

[9] W.P. Cumming, R.A. Skelton, D.B. Quinn, The Discovery of North America (New York: American Heritage Press, 1972), pp. 154-55; La Renaissance et le Nouveau Monde (Quebec: Musée du Québec, 1984), p. 89. The image of the ceremony is found at many places on the Internet.

[10] C.H. Laverdière, Œuvres de Champlain, 2d ed. (Quebec: Geo. Desbarats, 1870), vol. 3, pp. 451, 467, vol. 5, pp. 864, 879 ; Œuvres de Champlain présenté par Georges Émile Giguère (Montreal: Éditions du Jour, 1973), pp. 451, 466.

[11] Thwaites, The Jesuit Relations, vol. 55, pp. 104-15; biography of Simon-François Daumont de Saint-Lusson in Dictionary of Canadian Biography online: http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/daumont_de_saint_lusson_simon_francois_1E.html, consulted 8 January 2014.

[12] Naissance de la Louisiane, tricentenaire des découvertes de Cavelier de La Salle (Alençon, [France], 1982), pp. 12, 17 nos. 23-25 (exhibition catalogue). Biography of La Salle in Dictionary of Canadian Biography online: http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cavelier_de_la_salle_rene_robert_1E.html, consulted 15 January 2014.

[13] Biography of Louis-Joseph Gaultier de La Vérendrye and of François Gaultier du Tremblay in Dictionary of Canadian Biography online: http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gaultier_de_la_verendrye_louis_joseph_3E.html; http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gaultier_du_tremblay_francois_4E.html, consulted 24 January 2014; Antoine Champagne, Nouvelles études sur les La Vérendrye et le poste de l'Ouest (Quebec: Les Presses de l'Université Laval, 1971), pp. 87, 151-52.

[14] “Mémoire de Talon sur le Canada” (10 October 1670) in Rapport de l’archiviste de la province de Québec pour 1930-1931 (Quebec: Rédempti Paradis, 1931), p. 121.