Chapter 5

King Rules or Heralds Rule

The design of the arms of Canada had not reached England in time to be carved on the speaker’s chair. Instead, the old four-province shield had been used and this was thought to be “on the whole historically correct” as it was supposed that “the new arms do not come into existence until the Order-in-Council has been passed.” Sir George Perley, High Commissioner of Canada in London, was pleased that the matter of the chair had come up to expedite a decision and saw this as a diplomatic victory against the College of Heralds.

“ … I think however, it was well that this matter came up for decision at this particular juncture as of course the Colonial Office and the Heralds’ College were both pressed regarding it by the Empire Parliamentary Association and I judge that the Governor-General's despatch of April 30th was submitted directly through the Secretary of State for the Colonies and the King's approval given, without any consultation at that time with the Heralds’ College. It would also appear that when the latter heard of it, they still tried but without success, to get alterations made.... In any case I am very glad that the matter has been settled. I do not know much about Heraldry but like the design as put forward by the Committee and I feel sure that these Arms will give general satisfaction.”

Perley was sure that Pope had already discussed the situation with the secretary of the Empire Parliamentary Association, Sir Howard d'Egville, who knew more than him about the controversy.[1] Still, it was ironic that the old arms should appear on the chair since the new arms would be authorized, at least partly, because of that chair.

On 21 May 1921, Churchill wrote the Deputy Earl Marshal, Lord Fitzalan of Derwent, stressing that, because the king had approved the design and the Canadian government had been informed of the king's decision, there was no alternative but to accept the situation.[2] On June 11, the governor general cabled the Colonial Office asking, on behalf of his ministers, when the royal warrant granting the arms would be issued.[3] In retrospect, Conrad Swan analyses the situation as follows:

“Thus spoke the politician, but if Churchill thought that through the Deputy Earl Marshal he could move Garter to change his stand, he must have overlooked, for the moment at least, the fact that the incumbent of that office was Irish, one of a race which tends to become more stubborn, or more firm, depending on one's point of view, the more it senses opposition. Garter remained unshaken; he could see no adequate reason to alter his opinion, and further the Law Officers had not yet given their opinion.”[4]

In June, Mulvey was in England and paid a visit to the College of Heralds to ask Lee for a rendering of the arms of Lord Byng of Vimy who had been named Governor General of Canada. The rendering was required to have the vice-regal seal prepared. Lee was not there and Mulvey left a note and cheque with Everard Green, Somerset Herald, to have the work executed. An hour after Mulvey's departure, Somerset suddenly took ill, and when Lee saw the note, he did not recognize Mulvey's name and tore it up along with the cheque. Having realized his mistake, Lee informed Mulvey that he was having a copy of Byng's arms made for delivery within a week and was asking for a new note and cheque “with apologies for my stupidity in failing to read your name.”[5]

Mulvey also spoke with Garter and was able to learn of his specific reasons for being opposed to the Canadian design, one of which being that the fleurs-de-lis could be viewed as resurrecting the old claim to the throne of France. After England, Mulvey went to France and, on July 11, left a letter at the Commissariat général du Canada en France for the Honourable Philippe Roy, Commissioner for Canada in France. He explained that Garter had objected that the lilies might raise the old issue of the English claim to the French throne. He made it clear that their sole intention was to pay tribute to the origins of French Canadians whose ancestors had lived under the lilies of France. He further commented that, in the opinion of the committee, Garter was being “hypercritical”, but he felt the cause of the committee would be helped if France stated its position in this respect.[6] On July 19, Mulvey sent a telegram from England stating that the issue of arms was being held up because Garter was insisting that an order in council was necessary in the case of this grant. He was trying to get in touch with Doughty who was in England, but had not been able to find him. Back in Ottawa in August, Mulvey responded to a letter from Chadwick. He informed him that the objections that Garter had raised to their original design had been sent to the Colonial Office, but never transmitted to Canada.

“A report to this effect was made to the Colonial Office, and never communicated here. Subsequently a new device was submitted to His Majesty the King, which was approved of by him. It is now stated that this approval was given through a misunderstanding, it being taken for granted that when the first design, to which objection had been taken, was withdrawn and a new one submitted, the objection of Garter's report had been set aside. The authorities were thus at cross-purpose, Garter insisting upon his position because of his original report, and the Colonial Office unwilling to admit any neglect in respect of communicating that report. Garter, however, was rather willing that the matter should be taken out of his hands by an Imperial Order-in-Council, and I trusted Mr. Meighen to have this done.”[7]

As we have seen at the end of chapter 4, the committee members were aware that, by placing the sprig of maple at the base of the shield as requested by the king, they were not completely addressing Garter’s real objection to royal arms for Canada. The fact that Garter's Report had not been communicated to Canada had served their cause which was to pressure Garter into compliance by first obtaining the approval of the king. Now that the king's authorization had been secured, they were in a strong position to do just that.

Gwatkin made this clear to Mulvey: “For my own part, I venture to think that acting on the King's authority notified to us by the Secretary of State for the Colonies, we should ‘make it so and carry on’, leaving it to Garter and other malcontents to remove or circumvent the dummy obstacles that they themselves have raised.”[8] The notion that Garter’s objections were senseless was also expressed earlier by Frederick Ponsonby, Keeper of the Privy Purse for George V: “… it seems almost idiotic to insist on the fleur de lys being omitted for some silly technical reason.”[9]

In the meantime, Mulvey, besides seeking the help of Meighen, had thought of approaching the Countess of Minto, wife of the late Earl of Minto, governor general of Canada (1898-1904). Pope, who was on his annual holidays at Little Metis Beach, did not think the Countess of Minto should be approached, reasoning that, while she could have some personal influence on the king, his approval had already been secured. Rather than approach Meighen, who had succeeded Borden upon his retirement in July 1920 and was preparing for a general election in December, Pope thought it was best to press the Colonial Office for an answer to the governor general's question of June 11, as to when the granting document would be issued. If an imperial order in council was required, he felt this could be accomplished, as a precedent existed for the Great Seal of Prince Edward Island in 1769.[10]

Pope’s experience in external affairs had obviously convinced him that the best way to deal with such matters was through official channels and the wisdom of this approach could hardly be disputed. When Doughty tried to get further commitments through the Countess of Minto, he was informed that the king had seen the design and thought it looked “nice”, but could not express a view as to its artistic merits. Colonel Clive Wigram, a court official, expressed the hope that the heralds would not find fault with it.[11]

In the meantime, Commissioner Roy had acknowledged Mulvey's letter, but could not reply until the officials he wanted to consult returned to Paris.[12] On August 24, the Toronto Star reported the controversy and the need to secure both the approval of France and an order in council. Now that the arms had appeared in newspapers, Chadwick thought it opportune to offer further words of advice. He liked the supporters and motto, but found the shield too crowded. He thought the fleurs-de-lis could be introduced in some way as not to offend France such as a reversal of colours as in the 1868 arms of Quebec. Because Canada was not a kingdom, he was against the royal helmet and the crown, moreover that the latter was dangling in the air above the whole achievement. He insisted that the crest and helm should face in the same direction comparing the right angle arrangement to “a man half tipsy his hat awry.” Perhaps forgetting who he was writing to, he referred to the committee as having “only a limited knowledge of heraldry” which of course was true, but, on the advice of Todd, he would later apologize to Mulvey for his lack of tact.[13] Mulvey acknowledged his letter and said he would make his objections known to the committee.

On August 24, Mulvey wrote to the secretary of the prime minister of Canada:

“I find nothing was done in London to provide for the issue of the Warrant authorizing the new Arms of Canada. We are in the very curious position that the King has approved of them and the British Government Officials will take no action. I know Mr. Meighen is very busy, nevertheless I wish you would write a letter to the Colonial Secretary for him to sign, pressing for the issue of an Imperial Order in Council approving of new Arms. In order to assist this, I am preparing a formal despatch for the Colonial Office, which will go through the ordinary channels.”[14]

Mulvey, as under-secretary of state, then officially wrote Pope, as under-secretary for external affairs, asking if any progress had been made regarding the preparation of the imperial order in council.[15] Pope replied that nothing had transpired and that the governor general's cable of June 11 had remained unanswered. He recommended that they press for a reply.[16] The reason for the delay was that Garter was still awaiting a legal opinion from the Attorney General. On August 3, he had responded curtly to a letter from the Colonial Office: “I am not yet in a position to say when the Warrant will be ready for submission to His Majesty.”[17]

On September 2, a reply to Garter's objection to the fleurs-de-lis was sent by Louis Jaray, Chairman of the Committee France-Amérique and Maître des requêtes au Conseil d'État.

“...Upon reference of this matter to our President, we have much pleasure in affording you the following information: - We do not believe that the addition of the fleurs-de-lys to the coat-of-arms of Canada can reasonably be construed as a claim of rights over France by the Canadian Government. The idea which is behind the project you mention is simply to recall an historical fact; and, moreover, the fleurs-de-lys are no longer to be found in the French escutcheon.”

Jaray further recommended that, if “it was thought advisable to remove all kinds of difficulties and to conform strictly with heraldic precedents,” they could place three fleurs-de-lis horizontally and, above them, three maple leaves, all within the fourth quarter. The sprig of three maple leaves would remain in the lower shield so that a grouping of three maple leaves would appear twice, making the whole design even more complex.

“As you are perhaps aware, an escutcheon may, according to heraldic traditions, be charged with an alliance; this is Canada's case, and the ‘lys’ of France are the legacy of France to Canada. Of course the four other parts of the escutcheon would in nowise be altered, and, as planned, the lower part of the coat-of-arms would be used for the maple leaves of Canada as its principal charge.”[18]

Growing impatient, Gwatkin wrote Mulvey: “Pardon me, but ― damn The College of Arms. The King has spoken. I think we should take him at his word and carry on.”[19] Mulvey was in agreement with Gwatkin and informed him that he had just “sent a formal despatch through the Department of External Affairs, practically demanding that a warrant be issued in accordance with the King's direction...”[20]

On September 24, Mulvey received a letter from Garter which explained his reticence:

“Since our interview here I have been daily expecting to have a note from you arranging the further interview as to the arms of Canada. You will remember that I pointed out that the substitution of the arms of France in the fourth quarter for those of England was an alteration of the Royal Arms and, according to the Act of Union, could only be done by means of an Order in Council. Personally I think that apart from this, it has the objection that it heraldically revives the claim of the Crown of England to that of France.”

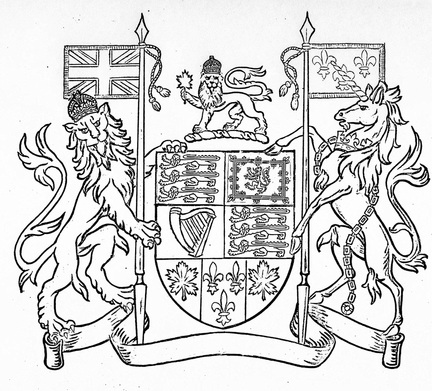

It now became clear that Garter's main objection, at least at this point, was not that Canada's arms should include the royal arms, but rather that Canada should create a new version of the royal arms since the latter were determined by the Act of Union of 1800 proclaimed in 1801. He included a sketch in which the arms of the royal arms were left intact, and the three fleurs-de-lis were moved in base between two maple leaves (fig.1).[21] Except for the matter of the royal arms, Garter’s proposal was not better than the Canadian one.

“ … I think however, it was well that this matter came up for decision at this particular juncture as of course the Colonial Office and the Heralds’ College were both pressed regarding it by the Empire Parliamentary Association and I judge that the Governor-General's despatch of April 30th was submitted directly through the Secretary of State for the Colonies and the King's approval given, without any consultation at that time with the Heralds’ College. It would also appear that when the latter heard of it, they still tried but without success, to get alterations made.... In any case I am very glad that the matter has been settled. I do not know much about Heraldry but like the design as put forward by the Committee and I feel sure that these Arms will give general satisfaction.”

Perley was sure that Pope had already discussed the situation with the secretary of the Empire Parliamentary Association, Sir Howard d'Egville, who knew more than him about the controversy.[1] Still, it was ironic that the old arms should appear on the chair since the new arms would be authorized, at least partly, because of that chair.

On 21 May 1921, Churchill wrote the Deputy Earl Marshal, Lord Fitzalan of Derwent, stressing that, because the king had approved the design and the Canadian government had been informed of the king's decision, there was no alternative but to accept the situation.[2] On June 11, the governor general cabled the Colonial Office asking, on behalf of his ministers, when the royal warrant granting the arms would be issued.[3] In retrospect, Conrad Swan analyses the situation as follows:

“Thus spoke the politician, but if Churchill thought that through the Deputy Earl Marshal he could move Garter to change his stand, he must have overlooked, for the moment at least, the fact that the incumbent of that office was Irish, one of a race which tends to become more stubborn, or more firm, depending on one's point of view, the more it senses opposition. Garter remained unshaken; he could see no adequate reason to alter his opinion, and further the Law Officers had not yet given their opinion.”[4]

In June, Mulvey was in England and paid a visit to the College of Heralds to ask Lee for a rendering of the arms of Lord Byng of Vimy who had been named Governor General of Canada. The rendering was required to have the vice-regal seal prepared. Lee was not there and Mulvey left a note and cheque with Everard Green, Somerset Herald, to have the work executed. An hour after Mulvey's departure, Somerset suddenly took ill, and when Lee saw the note, he did not recognize Mulvey's name and tore it up along with the cheque. Having realized his mistake, Lee informed Mulvey that he was having a copy of Byng's arms made for delivery within a week and was asking for a new note and cheque “with apologies for my stupidity in failing to read your name.”[5]

Mulvey also spoke with Garter and was able to learn of his specific reasons for being opposed to the Canadian design, one of which being that the fleurs-de-lis could be viewed as resurrecting the old claim to the throne of France. After England, Mulvey went to France and, on July 11, left a letter at the Commissariat général du Canada en France for the Honourable Philippe Roy, Commissioner for Canada in France. He explained that Garter had objected that the lilies might raise the old issue of the English claim to the French throne. He made it clear that their sole intention was to pay tribute to the origins of French Canadians whose ancestors had lived under the lilies of France. He further commented that, in the opinion of the committee, Garter was being “hypercritical”, but he felt the cause of the committee would be helped if France stated its position in this respect.[6] On July 19, Mulvey sent a telegram from England stating that the issue of arms was being held up because Garter was insisting that an order in council was necessary in the case of this grant. He was trying to get in touch with Doughty who was in England, but had not been able to find him. Back in Ottawa in August, Mulvey responded to a letter from Chadwick. He informed him that the objections that Garter had raised to their original design had been sent to the Colonial Office, but never transmitted to Canada.

“A report to this effect was made to the Colonial Office, and never communicated here. Subsequently a new device was submitted to His Majesty the King, which was approved of by him. It is now stated that this approval was given through a misunderstanding, it being taken for granted that when the first design, to which objection had been taken, was withdrawn and a new one submitted, the objection of Garter's report had been set aside. The authorities were thus at cross-purpose, Garter insisting upon his position because of his original report, and the Colonial Office unwilling to admit any neglect in respect of communicating that report. Garter, however, was rather willing that the matter should be taken out of his hands by an Imperial Order-in-Council, and I trusted Mr. Meighen to have this done.”[7]

As we have seen at the end of chapter 4, the committee members were aware that, by placing the sprig of maple at the base of the shield as requested by the king, they were not completely addressing Garter’s real objection to royal arms for Canada. The fact that Garter's Report had not been communicated to Canada had served their cause which was to pressure Garter into compliance by first obtaining the approval of the king. Now that the king's authorization had been secured, they were in a strong position to do just that.

Gwatkin made this clear to Mulvey: “For my own part, I venture to think that acting on the King's authority notified to us by the Secretary of State for the Colonies, we should ‘make it so and carry on’, leaving it to Garter and other malcontents to remove or circumvent the dummy obstacles that they themselves have raised.”[8] The notion that Garter’s objections were senseless was also expressed earlier by Frederick Ponsonby, Keeper of the Privy Purse for George V: “… it seems almost idiotic to insist on the fleur de lys being omitted for some silly technical reason.”[9]

In the meantime, Mulvey, besides seeking the help of Meighen, had thought of approaching the Countess of Minto, wife of the late Earl of Minto, governor general of Canada (1898-1904). Pope, who was on his annual holidays at Little Metis Beach, did not think the Countess of Minto should be approached, reasoning that, while she could have some personal influence on the king, his approval had already been secured. Rather than approach Meighen, who had succeeded Borden upon his retirement in July 1920 and was preparing for a general election in December, Pope thought it was best to press the Colonial Office for an answer to the governor general's question of June 11, as to when the granting document would be issued. If an imperial order in council was required, he felt this could be accomplished, as a precedent existed for the Great Seal of Prince Edward Island in 1769.[10]

Pope’s experience in external affairs had obviously convinced him that the best way to deal with such matters was through official channels and the wisdom of this approach could hardly be disputed. When Doughty tried to get further commitments through the Countess of Minto, he was informed that the king had seen the design and thought it looked “nice”, but could not express a view as to its artistic merits. Colonel Clive Wigram, a court official, expressed the hope that the heralds would not find fault with it.[11]

In the meantime, Commissioner Roy had acknowledged Mulvey's letter, but could not reply until the officials he wanted to consult returned to Paris.[12] On August 24, the Toronto Star reported the controversy and the need to secure both the approval of France and an order in council. Now that the arms had appeared in newspapers, Chadwick thought it opportune to offer further words of advice. He liked the supporters and motto, but found the shield too crowded. He thought the fleurs-de-lis could be introduced in some way as not to offend France such as a reversal of colours as in the 1868 arms of Quebec. Because Canada was not a kingdom, he was against the royal helmet and the crown, moreover that the latter was dangling in the air above the whole achievement. He insisted that the crest and helm should face in the same direction comparing the right angle arrangement to “a man half tipsy his hat awry.” Perhaps forgetting who he was writing to, he referred to the committee as having “only a limited knowledge of heraldry” which of course was true, but, on the advice of Todd, he would later apologize to Mulvey for his lack of tact.[13] Mulvey acknowledged his letter and said he would make his objections known to the committee.

On August 24, Mulvey wrote to the secretary of the prime minister of Canada:

“I find nothing was done in London to provide for the issue of the Warrant authorizing the new Arms of Canada. We are in the very curious position that the King has approved of them and the British Government Officials will take no action. I know Mr. Meighen is very busy, nevertheless I wish you would write a letter to the Colonial Secretary for him to sign, pressing for the issue of an Imperial Order in Council approving of new Arms. In order to assist this, I am preparing a formal despatch for the Colonial Office, which will go through the ordinary channels.”[14]

Mulvey, as under-secretary of state, then officially wrote Pope, as under-secretary for external affairs, asking if any progress had been made regarding the preparation of the imperial order in council.[15] Pope replied that nothing had transpired and that the governor general's cable of June 11 had remained unanswered. He recommended that they press for a reply.[16] The reason for the delay was that Garter was still awaiting a legal opinion from the Attorney General. On August 3, he had responded curtly to a letter from the Colonial Office: “I am not yet in a position to say when the Warrant will be ready for submission to His Majesty.”[17]

On September 2, a reply to Garter's objection to the fleurs-de-lis was sent by Louis Jaray, Chairman of the Committee France-Amérique and Maître des requêtes au Conseil d'État.

“...Upon reference of this matter to our President, we have much pleasure in affording you the following information: - We do not believe that the addition of the fleurs-de-lys to the coat-of-arms of Canada can reasonably be construed as a claim of rights over France by the Canadian Government. The idea which is behind the project you mention is simply to recall an historical fact; and, moreover, the fleurs-de-lys are no longer to be found in the French escutcheon.”

Jaray further recommended that, if “it was thought advisable to remove all kinds of difficulties and to conform strictly with heraldic precedents,” they could place three fleurs-de-lis horizontally and, above them, three maple leaves, all within the fourth quarter. The sprig of three maple leaves would remain in the lower shield so that a grouping of three maple leaves would appear twice, making the whole design even more complex.

“As you are perhaps aware, an escutcheon may, according to heraldic traditions, be charged with an alliance; this is Canada's case, and the ‘lys’ of France are the legacy of France to Canada. Of course the four other parts of the escutcheon would in nowise be altered, and, as planned, the lower part of the coat-of-arms would be used for the maple leaves of Canada as its principal charge.”[18]

Growing impatient, Gwatkin wrote Mulvey: “Pardon me, but ― damn The College of Arms. The King has spoken. I think we should take him at his word and carry on.”[19] Mulvey was in agreement with Gwatkin and informed him that he had just “sent a formal despatch through the Department of External Affairs, practically demanding that a warrant be issued in accordance with the King's direction...”[20]

On September 24, Mulvey received a letter from Garter which explained his reticence:

“Since our interview here I have been daily expecting to have a note from you arranging the further interview as to the arms of Canada. You will remember that I pointed out that the substitution of the arms of France in the fourth quarter for those of England was an alteration of the Royal Arms and, according to the Act of Union, could only be done by means of an Order in Council. Personally I think that apart from this, it has the objection that it heraldically revives the claim of the Crown of England to that of France.”

It now became clear that Garter's main objection, at least at this point, was not that Canada's arms should include the royal arms, but rather that Canada should create a new version of the royal arms since the latter were determined by the Act of Union of 1800 proclaimed in 1801. He included a sketch in which the arms of the royal arms were left intact, and the three fleurs-de-lis were moved in base between two maple leaves (fig.1).[21] Except for the matter of the royal arms, Garter’s proposal was not better than the Canadian one.

Fig. 1 Arms proposed for Canada by Garter King of Arms in September 1921. LAC RG 6, A1, vol. 210, file 1156, part 3.

|

Fig. 2 Fleurs-de-lis appeared in the shield of England from 1340 to affirm Edward III’s claim to the throne of France. They remained there until 1801. The above arms illustrate a map of Newfoundland by John Mason, 1616 or 1617, published in William Vaughan, Cambrensium Caroleia, London, 1625.

|

Fig. 3 Fleurs-de-lis are seen in the upper right quarter of this version of the royal arms impressed into paper used as a stamp to authenticate legal documents in British colonies, 1765. Library and Archives Canada, RG 4, B16, vol. 1, photo C -83435

|

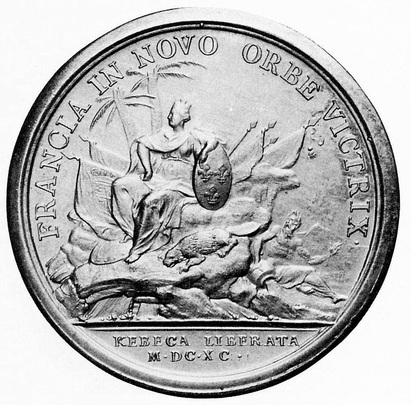

It is debatable whether the permission of republican France was required to use the arms of royal France in a historical sense. They were an intimate part of life in New France and, in the arms of Canada, they merely expressed heritage and origin. In this context, they were surely not used as arms of dominion or sovereignty, nor were they meant to represent any particular royal house. When the fleurs-de-lis were introduced into the arms of the Province of Quebec in 1868, we were not far away from the reign of Louis-Philippe (1830-48) and Napoleon III was on the throne as Emperor of France. Introducing the royal arms of France unaltered into Canadian arms at that time might have raised eyebrows in view of their former use in the arms of England as a claim to the French throne. In 1921, on the other hand, the French throne no longer existed and it seems a little far-fetched to exclude the lilies from the arms of Canada, used simply as an historical allusion, on the off chance that the monarchy might someday be restored in France.

|

Fig. 4 Kebeca liberata Medal by Jean Mauger, obverse. Celebrating Frontenac’s victory over Admiral Phipps at the siege of Quebec City in 1690. Library and Archives Canada, photo C-115686 (obverse) and C-115685 (reverse).

|

Fig. 5 Reverse of fig. 4. We have seen in chapter 2 the presence of the arms of Royal France in many aspects of life in New France. Here they are held by an allegorical female figure representing France with a beaver representing Canada below.

|

On September 29, Pope summarized the situation as follows:

“Had a meeting of the Arms Committee today at which we definitely decided to proceed with the adoption of the new Canadian Arms despite the opposition of the Herald’s College. This attitude―a most unusual one for me―is justified by the fact that the King had approved our draft, and that this approval was officially communicated to us by His Majesty’s responsible Minister, the Secretary of State for the Colonies. This is enough for me. The Heralds raise all sorts of objections, some puerile as I think, so supported by H.M.’s sanction we are going ahead. Our Arms are very handsome, loyal, British Monarchical with due recognition of Canada, in fact everything that can be desired. The motto ‘A Mari usque ad Mare’, which is an original suggestion of my own, I regard as very appropriate.”[22]

What Pope was not saying was that the committee had gone to the king to go over Garter’s head, something he did not have to do in his previous dealing with the College of Heralds to obtain arms for several provinces. A few days later, Mulvey told Garter that the committee had discussed the matter of possible alterations to the arms on several occasions and had concluded that no alterations should be made now that the king had approved them and that a formal despatch had been sent to the secretary of state for the colonies requesting that the order in council be issued: “… it is now too late to recede from the position we have taken.”[23]

It was not until October 24, that the attorney general offered the opinion that the king could proceed with the grant by a royal proclamation. Garter was now assured that he was acting with complete legality and felt that the Colonial Office had been “properly strafed.”[24] It seems that Garter blamed the Colonial Office for not transmitting to Canada his original report, for getting the king’s approval without consulting him and for constantly putting pressure on him. However, most of his troubles had been the result of manoeuvres by Canadians. He surely must have been annoyed with the arms committee as well, but while the committee was highly critical of him, he does not seem to have reciprocated.

Was Garter being overly fussy and difficult, as Canadians and some British officials believed, or was his extreme prudence justified in spite of the king’s authorization and the Colonial Office's promptings? It is certain that he did not believe royal arms to be appropriate for Canada, which he probably viewed more or less as a colony. He wanted something simpler with greater Canadian content. Moreover, the granting of a form of royal arms would, in his view, contravene a law of the British Parliament and potentially cause a diplomatic incident with France. Garter had been pictured as an obstructionist in several quarters, but if anything had gone wrong, he may well have become scapegoat. On the other hand, if Garter had believed as York did “that the Canadian Government's position is strong enough to ensure their getting what they may decide to ask for,”[25] the matter could have been resolved with a minimum of fuss. Garter’s view did not seem to take into account that, with the British North America Act, Canada had become virtually self-governing internally and was at the time quickly approaching the same status in its external affairs. Of course the country only became a sovereign nation in 1931 by the Statute of Westminster and it was only in 1953 that the styles and title of Queen Elizabeth were changed to include “Queen of Canada.”

“Had a meeting of the Arms Committee today at which we definitely decided to proceed with the adoption of the new Canadian Arms despite the opposition of the Herald’s College. This attitude―a most unusual one for me―is justified by the fact that the King had approved our draft, and that this approval was officially communicated to us by His Majesty’s responsible Minister, the Secretary of State for the Colonies. This is enough for me. The Heralds raise all sorts of objections, some puerile as I think, so supported by H.M.’s sanction we are going ahead. Our Arms are very handsome, loyal, British Monarchical with due recognition of Canada, in fact everything that can be desired. The motto ‘A Mari usque ad Mare’, which is an original suggestion of my own, I regard as very appropriate.”[22]

What Pope was not saying was that the committee had gone to the king to go over Garter’s head, something he did not have to do in his previous dealing with the College of Heralds to obtain arms for several provinces. A few days later, Mulvey told Garter that the committee had discussed the matter of possible alterations to the arms on several occasions and had concluded that no alterations should be made now that the king had approved them and that a formal despatch had been sent to the secretary of state for the colonies requesting that the order in council be issued: “… it is now too late to recede from the position we have taken.”[23]

It was not until October 24, that the attorney general offered the opinion that the king could proceed with the grant by a royal proclamation. Garter was now assured that he was acting with complete legality and felt that the Colonial Office had been “properly strafed.”[24] It seems that Garter blamed the Colonial Office for not transmitting to Canada his original report, for getting the king’s approval without consulting him and for constantly putting pressure on him. However, most of his troubles had been the result of manoeuvres by Canadians. He surely must have been annoyed with the arms committee as well, but while the committee was highly critical of him, he does not seem to have reciprocated.

Was Garter being overly fussy and difficult, as Canadians and some British officials believed, or was his extreme prudence justified in spite of the king’s authorization and the Colonial Office's promptings? It is certain that he did not believe royal arms to be appropriate for Canada, which he probably viewed more or less as a colony. He wanted something simpler with greater Canadian content. Moreover, the granting of a form of royal arms would, in his view, contravene a law of the British Parliament and potentially cause a diplomatic incident with France. Garter had been pictured as an obstructionist in several quarters, but if anything had gone wrong, he may well have become scapegoat. On the other hand, if Garter had believed as York did “that the Canadian Government's position is strong enough to ensure their getting what they may decide to ask for,”[25] the matter could have been resolved with a minimum of fuss. Garter’s view did not seem to take into account that, with the British North America Act, Canada had become virtually self-governing internally and was at the time quickly approaching the same status in its external affairs. Of course the country only became a sovereign nation in 1931 by the Statute of Westminster and it was only in 1953 that the styles and title of Queen Elizabeth were changed to include “Queen of Canada.”

|

Fig. 6 Great Seal of Charles I, as King of Scotland (obverse), appended to a charter creating Sir Duncan Campbell of Glenorchy a Baronet of Nova Scotia in 1625. Library and Archives Canada, MG 18, F 36, photos C-131775 and C-131774.

|

Fig. 7 Reverse of fig. 6. When James I ascended the throne of England in 1603, he was already James VI of Scotland. He used different arms for each kingdom, the ones above being those for Scotland as used by him and his successor Charles I.

|

|

Fig. 8 Present royal arms as used in Scotland. The practice of having different royal arms for England and Scotland inspired the idea of obtaining a version of royal arms for Canada.

|

Fig. 9 Present royal arms as used in England from which many of the components of the royal arms of Canada are derived. Figs 8 & 9 are drawn by Alan Beddoe, from Heraldry in Canada 2, no. 5 (1967), p. 20.

|

On November 25, Churchill sent Byng the king's proclamation granting arms to Canada.[26] The proclamation specified that the king was acting “… with the advice of Our Privy Council, and in exercise of the powers conferred by the first Article of the Union with Ireland Act, 1800 …”[27] It is interesting that the Union Act of 1800, which was such a concern for Garter because it fixed the composition of the royal arms, contained, in the very wording of the first article, a solution to the dilemma: “...that the Royal Stile and Titles appertaining to the Imperial Crown of the said United Kingdom and its Dependencies, and also the Ensigns Armorial Flags and Banners thereof shall be such as his Majesty, by his Royal Proclamation under the Great Seal of the United Kingdom, shall be pleased to appoint.”

The article clearly states the sovereign is empowered by royal proclamation under the Great Seal to confer upon one of his dependencies the arms he/she wished. The royal arms of the United Kingdom themselves had been changed three times since 1801. When Garter saw a clear solution to the impasse, he acted quickly, but he surely knew about the first article of the Union Act and this raises again the question as to whether obtaining legal advice on the matter may have been a delay tactic.

In the proclamation, the maple leaves in base of the shield are not described as vert (green) but as proper meaning that they could be eventually depicted green, gold, red or multicoloured. One curious discrepancy crept up in the mantling. In the wording of the proclamation, the colours in the mantling are white on the outside and red on the inside: “And upon a Royal helmet mantled Argent doubled Gules …” This seems a mistake. Anyone who has worked on grants of arms knows how easily such slips can happen. Later on, when a certified copy of the proclamation was sent to Canada, the mantling in the accompanying drawing was red on the outside and white on the inside as it should have been in the wording. It should be noted also that the drawing on the copy of the proclamation certified by Garter’s seal was in fact almost identical to the one sent to England by the committee.[28]

Except for the fact that it was in imitation of the arms of the Royal Military College, one wonders why the crown is placed above the entire achievement and not above the helmet as in the royal arms of England, those of Scotland and in the later augmentations to the arms of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and British Columbia. This seems unusual, all the more so that, from a design point of view, the whole would look better if the crown were integrated with the helmet.

A more crucial question was whether Canada had been granted royal arms? The word “royal arms” is not found in the proclamation. This is perhaps normal since the Canadian order in council of 30 April 1921 had not requested a grant of royal arms for Canada. The proclamation specified that the king was exercising powers conferred to him by the first article of the 1800 Act of Union with Ireland, but this document simply empowers the sovereign to grant arms to dependencies by proclamation under the Great Seal. It does not state that such arms are to be royal arms. Nor does the fact that the arms were granted by royal proclamation necessarily justify the appellation royal. The flag of Canada was granted by a royal proclamation in which it is referred to as the National Flag of Canada. It would seem strange to call it the Royal National Flag of Canada. The Great Seal of Canada shows the queen enthroned with sceptre and orb, the arms of Canada in the base and the inscription: “Elizabeth II Queen of Canada.” Although this instrument is eminently royal, we do not normally refer to it as the Royal Great Seal of Canada. Adding the adjective royal to the Great Seal, somehow, seems exaggerated.

In the absence of a legal document to that effect, could the arms granted to Canada be royal simply by virtue of their composition? The mention in the proclamation of a “Royal helmet” on top of the shield, of a lion “imperially crowned” on top of the helmet and of an “Imperial Crown” on top of it all, along with other elements taken from the royal arms of the United Kingdom surely signifies a very close relation with the sovereign, but royal content does not necessarily mean royal arms. The sovereign sometimes grants royal symbols as a special favour such as the crown above the arms of the Royal Military College, which does not by that fact make them royal arms, unless the term is used in a rather broad sense. Garter felt that the design was altering the royal arms of the United Kingdom, but he was perhaps just being extra cautious or thought that, by creating enough obstacles, Canada would accept something else.

Can we today argue that the arms of Canada are not royal arms? This has been done as late as 1978 by LtCol. N.A. Buckingham, Director of Ceremonial in the Canadian Forces Headquarters. Buckingham's argument is mostly based on the wording of the proclamation: “...nowhere have I been able to find mention of the ‘Royal Arms of Canada’ in any official document or authoritative work on heraldry. Therefore, I repeat, we as a Society, [Heraldry Society of Canada] would do well to take our lead from the Royal Proclamation as well as the recognized authorities and refrain from inventing expressions such as ‘The Royal Arms of Canada’.”[29] Of course, LtCol. Buckingham was correct in stating that “Royal Arms of Canada” is not to be found in the proclamation or other official documents preceding the proclamation, but other developments came into play that leave little doubt as to the nature of the arms.

Dr. Swan states that with the Statute of Westminster the arms of Canada became “arms of Dominion and Sovereignty.”[30] These are defined as the arms “used by a sovereign in the territories over which he/she has Dominion.”[31] On George VI’s Great Seal of Canada authorized in 1940, we no longer see the arms of the United Kingdom under the enthroned king, but those granted to Canada in 1921.[32] This would seem to confirm that they are viewed as the sovereign's royal arms for Canada. In 1953, Queen Elizabeth II acquired the title of Queen of Canada. Her new title appeared with her enthroned figure along with the arms of Canada on Canada's Great Seal. The Great Seal being as official a document as can be; it seems clear that the arms engraved on it were Her Majesty's royal arms for Canada. In 1962, she adopted a personal flag for use when in Canada mostly based on the arms of the country, and in 1963, she granted the Right Honourable Vincent Massey an honourable augmentation to his coat of arms which was described as “Our Crest of Canada.”[33] If the crest was that of Her Majesty for Canada, so were the entire arms, obviously.

If the arms of Canada are really royal arms of the country, why does the government not declare this openly? In fact it has done just that, although not in the early publications of the Secretary of State on the arms of Canada, from the first edition of 1921up to the fifth edition of 1947. In the 1964 edition, on the other hand, this is stated unequivocally: “Just as in Britain where the Sovereign has royal arms for use in England and different royal arms for use in Scotland, the Arms of Canada are royal arms approved for use in Canada.” On a poster accompanying The Canadian Symbols Kit, published in 1967 by the Department of the Secretary of State, the caption reads “The Royal Arms of Canada.” However the term royal is often omitted in favour of simply: “The Arms of Canada”

***

The Canadian committee had conceived the coat of arms of the country in accordance with certain principles which made them very close in design to the royal arms of the United Kingdom. When Canadians learned unofficially that Garter King of Arms was opposed to their design, they decided to first obtain approval of the king, so that heralds would have to comply with their wishes. For Garter, the composition of the design was an alteration of the royal arms as determined by the Act of Union of 1800. Because Canadians were unwilling to make changes, he established through legal advice that a new proclamation was needed. The proclamation of 1921 did not state that the arms granted were royal arms and the Secretary of State avoided this designation in its early publications on the subject. Future developments, such as the adoption in 1962 of a Royal Standard for Canada by Queen Elizabeth II, basically a banner of the Canadian arms, made it evident that this emblem was that of the sovereign for use in Canada. Nevertheless, the word royal is often omitted when referring to Canada’s coat of arms.

Obtaining armorial bearings for Canada was not an easy task, but the story of Canada’s arms was by no means over as we shall see.

The article clearly states the sovereign is empowered by royal proclamation under the Great Seal to confer upon one of his dependencies the arms he/she wished. The royal arms of the United Kingdom themselves had been changed three times since 1801. When Garter saw a clear solution to the impasse, he acted quickly, but he surely knew about the first article of the Union Act and this raises again the question as to whether obtaining legal advice on the matter may have been a delay tactic.

In the proclamation, the maple leaves in base of the shield are not described as vert (green) but as proper meaning that they could be eventually depicted green, gold, red or multicoloured. One curious discrepancy crept up in the mantling. In the wording of the proclamation, the colours in the mantling are white on the outside and red on the inside: “And upon a Royal helmet mantled Argent doubled Gules …” This seems a mistake. Anyone who has worked on grants of arms knows how easily such slips can happen. Later on, when a certified copy of the proclamation was sent to Canada, the mantling in the accompanying drawing was red on the outside and white on the inside as it should have been in the wording. It should be noted also that the drawing on the copy of the proclamation certified by Garter’s seal was in fact almost identical to the one sent to England by the committee.[28]

Except for the fact that it was in imitation of the arms of the Royal Military College, one wonders why the crown is placed above the entire achievement and not above the helmet as in the royal arms of England, those of Scotland and in the later augmentations to the arms of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and British Columbia. This seems unusual, all the more so that, from a design point of view, the whole would look better if the crown were integrated with the helmet.

A more crucial question was whether Canada had been granted royal arms? The word “royal arms” is not found in the proclamation. This is perhaps normal since the Canadian order in council of 30 April 1921 had not requested a grant of royal arms for Canada. The proclamation specified that the king was exercising powers conferred to him by the first article of the 1800 Act of Union with Ireland, but this document simply empowers the sovereign to grant arms to dependencies by proclamation under the Great Seal. It does not state that such arms are to be royal arms. Nor does the fact that the arms were granted by royal proclamation necessarily justify the appellation royal. The flag of Canada was granted by a royal proclamation in which it is referred to as the National Flag of Canada. It would seem strange to call it the Royal National Flag of Canada. The Great Seal of Canada shows the queen enthroned with sceptre and orb, the arms of Canada in the base and the inscription: “Elizabeth II Queen of Canada.” Although this instrument is eminently royal, we do not normally refer to it as the Royal Great Seal of Canada. Adding the adjective royal to the Great Seal, somehow, seems exaggerated.

In the absence of a legal document to that effect, could the arms granted to Canada be royal simply by virtue of their composition? The mention in the proclamation of a “Royal helmet” on top of the shield, of a lion “imperially crowned” on top of the helmet and of an “Imperial Crown” on top of it all, along with other elements taken from the royal arms of the United Kingdom surely signifies a very close relation with the sovereign, but royal content does not necessarily mean royal arms. The sovereign sometimes grants royal symbols as a special favour such as the crown above the arms of the Royal Military College, which does not by that fact make them royal arms, unless the term is used in a rather broad sense. Garter felt that the design was altering the royal arms of the United Kingdom, but he was perhaps just being extra cautious or thought that, by creating enough obstacles, Canada would accept something else.

Can we today argue that the arms of Canada are not royal arms? This has been done as late as 1978 by LtCol. N.A. Buckingham, Director of Ceremonial in the Canadian Forces Headquarters. Buckingham's argument is mostly based on the wording of the proclamation: “...nowhere have I been able to find mention of the ‘Royal Arms of Canada’ in any official document or authoritative work on heraldry. Therefore, I repeat, we as a Society, [Heraldry Society of Canada] would do well to take our lead from the Royal Proclamation as well as the recognized authorities and refrain from inventing expressions such as ‘The Royal Arms of Canada’.”[29] Of course, LtCol. Buckingham was correct in stating that “Royal Arms of Canada” is not to be found in the proclamation or other official documents preceding the proclamation, but other developments came into play that leave little doubt as to the nature of the arms.

Dr. Swan states that with the Statute of Westminster the arms of Canada became “arms of Dominion and Sovereignty.”[30] These are defined as the arms “used by a sovereign in the territories over which he/she has Dominion.”[31] On George VI’s Great Seal of Canada authorized in 1940, we no longer see the arms of the United Kingdom under the enthroned king, but those granted to Canada in 1921.[32] This would seem to confirm that they are viewed as the sovereign's royal arms for Canada. In 1953, Queen Elizabeth II acquired the title of Queen of Canada. Her new title appeared with her enthroned figure along with the arms of Canada on Canada's Great Seal. The Great Seal being as official a document as can be; it seems clear that the arms engraved on it were Her Majesty's royal arms for Canada. In 1962, she adopted a personal flag for use when in Canada mostly based on the arms of the country, and in 1963, she granted the Right Honourable Vincent Massey an honourable augmentation to his coat of arms which was described as “Our Crest of Canada.”[33] If the crest was that of Her Majesty for Canada, so were the entire arms, obviously.

If the arms of Canada are really royal arms of the country, why does the government not declare this openly? In fact it has done just that, although not in the early publications of the Secretary of State on the arms of Canada, from the first edition of 1921up to the fifth edition of 1947. In the 1964 edition, on the other hand, this is stated unequivocally: “Just as in Britain where the Sovereign has royal arms for use in England and different royal arms for use in Scotland, the Arms of Canada are royal arms approved for use in Canada.” On a poster accompanying The Canadian Symbols Kit, published in 1967 by the Department of the Secretary of State, the caption reads “The Royal Arms of Canada.” However the term royal is often omitted in favour of simply: “The Arms of Canada”

***

The Canadian committee had conceived the coat of arms of the country in accordance with certain principles which made them very close in design to the royal arms of the United Kingdom. When Canadians learned unofficially that Garter King of Arms was opposed to their design, they decided to first obtain approval of the king, so that heralds would have to comply with their wishes. For Garter, the composition of the design was an alteration of the royal arms as determined by the Act of Union of 1800. Because Canadians were unwilling to make changes, he established through legal advice that a new proclamation was needed. The proclamation of 1921 did not state that the arms granted were royal arms and the Secretary of State avoided this designation in its early publications on the subject. Future developments, such as the adoption in 1962 of a Royal Standard for Canada by Queen Elizabeth II, basically a banner of the Canadian arms, made it evident that this emblem was that of the sovereign for use in Canada. Nevertheless, the word royal is often omitted when referring to Canada’s coat of arms.

Obtaining armorial bearings for Canada was not an easy task, but the story of Canada’s arms was by no means over as we shall see.

Notes

LAC = Library and Archives Canada

RG 6 = Secretary of State papers

[1] LAC, RG 6, A1, vol. 210, file 1156, part 2, pp. 86-87, Perley to Pope, 18 May 1921.

[2] Conrad Swan, Canada Symbols of Sovereignty (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1960), p. 63.

[3] LAC, RG 6, A1, vol. 210, file 1156, part 2, p. 6, Pope to Mulvey, 14 September 1921.

[4] Swan, Canada Symbols of Sovereignty, p. 63.

[5] LAC, RG 6, A1, vol. 210, file 1156, part 2, p. 64, Lee to Mulvey, 23 June 1921.

[6] Ibid., pp. 61-63, Mulvey to Roy, 11 July, 1921.

[7] Ibid., p. 48, Mulvey to Chadwick, 15 August 1921.

[8] Ibid., p. 45, Gwatkin to Mulvey, 16 August 1921.

[9] LAC, RG 30, D26, vol. 2, Ponsonby to the Countess of Minto, 28 October 1920.

[10] LAC, RG 6, A1, vol. 210, file 1156, part 2, p. 30, Pope to Mulvey, 22 August 1921.

[11] LAC, RG 30, D26, vol. 2, Wigram to the Countess of Minto, 1 August 1920.

[12] LAC, RG 6, A1, vol. 210, file 1156, part 2, p. 29, Roy to Mulvey, 23 August 1921.

[13] Ibid., pp. 10-13; part 3, p. 363. Chadwick to Mulvey, 31 August and 5 September 1921.

[14] Ibid., p. 26, Mulvey to Armstrong, 24 August 1921.

[15] Ibid., p. 7, Mulvey to Pope, 13 September 1921.

[16] Ibid., p. 6, Pope to Mulvey, 14 September 1921.

[17] Swan, Canada Symbols of Sovereignty, p. 63.

[18] LAC RG 6, A1, vol. 210, file 1156, part 3, pp. 352-55, Jaray to Roy, 2 September 1921 (includes the original French text and the English translation).

[19] Ibid., p. 357, Gwatkin to Mulvey, 17 September 1921.

[20] Ibid., p. 356, Mulvey to Gwatkin, 19 September 1921.

[21] Ibid., pp. 350-351, Burke to Mulvey, 13 September 1921.

[22] Maurice Pope ed., Public Servant: the Memoirs of Sir Joseph Pope (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1960), p. 283.

[23] LAC, RG 6, A1, vol. 210, file 1156, part 3, p. 339, Mulvey to Burke, 3 October 1921.

[24] Swan, Canada Symbols of Sovereignty, p. 63.

[25] Ibid.

[26] LAC, RG 6, A1, vol. 210, file 1156, part 3, pp. 264, 275, Telegram of Churchill to Byng, 24 November 1921 and letter of Churchill to Byng, 25 November 1921.

[27] Proclamation printed in: Secretary of State, The arms of Canada, 2d ed. (Ottawa: F.A. Acland, 1923), p. 3.

[28] These two documents are reproduced in Auguste Vachon, "Significant documents" in The Archivist 18, no. 1 (January-June 1991), pp. 2-3; LAC, RG 6, A9 , vol. 1; RG 6, A1, vol. 210: file: "Arms of Canada".

[29] “Letter to the Editor from LtCol. N.A. Buckingham” in Heraldry in Canada 12, no. 1 (March 1978), pp. 27-28; "Letter to the Editor from LtCol. N. A. Buckingham" in Heraldry in Canada 12, no. 3 (September 1978), p. 7.

[30] Swan, Canada Symbols of Sovereignty, pp. 32-33.

[31] Stephen Friar, ed., A New Dictionary of Heraldry (London: A & C Black, 1987), p. 27.

[32] Swan, Canada Symbols of Sovereignty, p. 74.

[33] "Warrant of Queen Elizabeth II augmenting the arms of the Right Honourable, Charles Vincent Massey, 11 December 1963" in Alan Beddoe, Beddoe's Canadian Heraldry, revised by Col. Strome Galloway (Belleville, Ontario: Mica Publishing Company, 1981), p. 173.

LAC = Library and Archives Canada

RG 6 = Secretary of State papers

[1] LAC, RG 6, A1, vol. 210, file 1156, part 2, pp. 86-87, Perley to Pope, 18 May 1921.

[2] Conrad Swan, Canada Symbols of Sovereignty (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1960), p. 63.

[3] LAC, RG 6, A1, vol. 210, file 1156, part 2, p. 6, Pope to Mulvey, 14 September 1921.

[4] Swan, Canada Symbols of Sovereignty, p. 63.

[5] LAC, RG 6, A1, vol. 210, file 1156, part 2, p. 64, Lee to Mulvey, 23 June 1921.

[6] Ibid., pp. 61-63, Mulvey to Roy, 11 July, 1921.

[7] Ibid., p. 48, Mulvey to Chadwick, 15 August 1921.

[8] Ibid., p. 45, Gwatkin to Mulvey, 16 August 1921.

[9] LAC, RG 30, D26, vol. 2, Ponsonby to the Countess of Minto, 28 October 1920.

[10] LAC, RG 6, A1, vol. 210, file 1156, part 2, p. 30, Pope to Mulvey, 22 August 1921.

[11] LAC, RG 30, D26, vol. 2, Wigram to the Countess of Minto, 1 August 1920.

[12] LAC, RG 6, A1, vol. 210, file 1156, part 2, p. 29, Roy to Mulvey, 23 August 1921.

[13] Ibid., pp. 10-13; part 3, p. 363. Chadwick to Mulvey, 31 August and 5 September 1921.

[14] Ibid., p. 26, Mulvey to Armstrong, 24 August 1921.

[15] Ibid., p. 7, Mulvey to Pope, 13 September 1921.

[16] Ibid., p. 6, Pope to Mulvey, 14 September 1921.

[17] Swan, Canada Symbols of Sovereignty, p. 63.

[18] LAC RG 6, A1, vol. 210, file 1156, part 3, pp. 352-55, Jaray to Roy, 2 September 1921 (includes the original French text and the English translation).

[19] Ibid., p. 357, Gwatkin to Mulvey, 17 September 1921.

[20] Ibid., p. 356, Mulvey to Gwatkin, 19 September 1921.

[21] Ibid., pp. 350-351, Burke to Mulvey, 13 September 1921.

[22] Maurice Pope ed., Public Servant: the Memoirs of Sir Joseph Pope (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1960), p. 283.

[23] LAC, RG 6, A1, vol. 210, file 1156, part 3, p. 339, Mulvey to Burke, 3 October 1921.

[24] Swan, Canada Symbols of Sovereignty, p. 63.

[25] Ibid.

[26] LAC, RG 6, A1, vol. 210, file 1156, part 3, pp. 264, 275, Telegram of Churchill to Byng, 24 November 1921 and letter of Churchill to Byng, 25 November 1921.

[27] Proclamation printed in: Secretary of State, The arms of Canada, 2d ed. (Ottawa: F.A. Acland, 1923), p. 3.

[28] These two documents are reproduced in Auguste Vachon, "Significant documents" in The Archivist 18, no. 1 (January-June 1991), pp. 2-3; LAC, RG 6, A9 , vol. 1; RG 6, A1, vol. 210: file: "Arms of Canada".

[29] “Letter to the Editor from LtCol. N.A. Buckingham” in Heraldry in Canada 12, no. 1 (March 1978), pp. 27-28; "Letter to the Editor from LtCol. N. A. Buckingham" in Heraldry in Canada 12, no. 3 (September 1978), p. 7.

[30] Swan, Canada Symbols of Sovereignty, pp. 32-33.

[31] Stephen Friar, ed., A New Dictionary of Heraldry (London: A & C Black, 1987), p. 27.

[32] Swan, Canada Symbols of Sovereignty, p. 74.

[33] "Warrant of Queen Elizabeth II augmenting the arms of the Right Honourable, Charles Vincent Massey, 11 December 1963" in Alan Beddoe, Beddoe's Canadian Heraldry, revised by Col. Strome Galloway (Belleville, Ontario: Mica Publishing Company, 1981), p. 173.