Un écu fictif pour Samuel de Champlain / A Fictitious Shield for Samuel de Champlain

Un écu fictif pour Samuel de Champlain

Vers le milieu de son mandat comme gouverneur général du Canada, le très honorable Jules Léger avait conçu l’idée de créer une galerie de portraits des gouverneurs généraux depuis l’époque coloniale jusqu’à lui. Après des recherches poussées menées par mes collègues et moi du service iconographiques des Archives nationales du Canada, force était de constater qu’il n’existait pas de portraits authentiques pour environ les deux tiers des gouverneurs généraux du temps de la Nouvelle-France. Léger revint à la charge avec l’idée d’un panneau arborant les armoiries et les noms des gouverneurs.

Ma participation au projet consistait à fournir à l’artiste Art Price d’Ottawa une illustration des armoiries et à vérifier l’exactitude du travail peint en couleurs. Un seul problème à l’horizon! Des recherches menées depuis plusieurs années n’avaient pas révélé d’armoiries pour Samuel de Champlain. Un événement tend à confirmer qu’il n’en possédait pas. Le 6 mai 1624, la pierre qu’il posa dans les fondations de sa deuxième habitation était gravée des armes du roi, de celles d’Henri II, duc de Montmorency et vice-roi de la Nouvelle-France, de son nom comme lieutenant d’Henri II et de la date de l’événement (Laverdière, Œuvres de Champlain, vol. 5, pp. 1057-58). S’il avait possédé des armoiries, c’était le moment par excellence de les faire graver avec les deux autres.

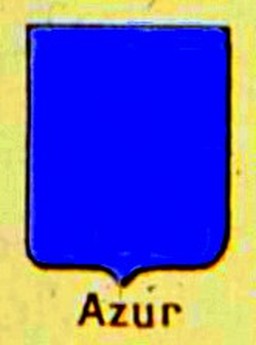

Le plus facile aurait été d’éliminer Champlain du panthéon puisqu’il n’avait pas le titre de gouverneur, même si ses pouvoirs auraient pu justifier cette désignation. Mais il s’agissait d’une décision déjà prise; son nom figurait déjà sur le panneau qui allait recevoir les écus armoriés. On avait proposé de le représenter par une fleur de lis, mais je savais par expérience que, si on choisissait cette figure, elle serait éventuellement reproduite comme étant ses armoiries authentiques. Par bonheur, le vocabulaire héraldique contenait une solution en perspective. Champ plain (ou plein) signifie en héraldique qu’un écu est rempli d’un seul émail. Ceci m’inspira l’idée de mettre sur l’écu réservé à Champlain un champ plain d’azur dit d’azur plain en langue du blason. Son Excellence accepta avec enthousiasme cette proposition qui l’amusait beaucoup.

Vers le milieu de son mandat comme gouverneur général du Canada, le très honorable Jules Léger avait conçu l’idée de créer une galerie de portraits des gouverneurs généraux depuis l’époque coloniale jusqu’à lui. Après des recherches poussées menées par mes collègues et moi du service iconographiques des Archives nationales du Canada, force était de constater qu’il n’existait pas de portraits authentiques pour environ les deux tiers des gouverneurs généraux du temps de la Nouvelle-France. Léger revint à la charge avec l’idée d’un panneau arborant les armoiries et les noms des gouverneurs.

Ma participation au projet consistait à fournir à l’artiste Art Price d’Ottawa une illustration des armoiries et à vérifier l’exactitude du travail peint en couleurs. Un seul problème à l’horizon! Des recherches menées depuis plusieurs années n’avaient pas révélé d’armoiries pour Samuel de Champlain. Un événement tend à confirmer qu’il n’en possédait pas. Le 6 mai 1624, la pierre qu’il posa dans les fondations de sa deuxième habitation était gravée des armes du roi, de celles d’Henri II, duc de Montmorency et vice-roi de la Nouvelle-France, de son nom comme lieutenant d’Henri II et de la date de l’événement (Laverdière, Œuvres de Champlain, vol. 5, pp. 1057-58). S’il avait possédé des armoiries, c’était le moment par excellence de les faire graver avec les deux autres.

Le plus facile aurait été d’éliminer Champlain du panthéon puisqu’il n’avait pas le titre de gouverneur, même si ses pouvoirs auraient pu justifier cette désignation. Mais il s’agissait d’une décision déjà prise; son nom figurait déjà sur le panneau qui allait recevoir les écus armoriés. On avait proposé de le représenter par une fleur de lis, mais je savais par expérience que, si on choisissait cette figure, elle serait éventuellement reproduite comme étant ses armoiries authentiques. Par bonheur, le vocabulaire héraldique contenait une solution en perspective. Champ plain (ou plein) signifie en héraldique qu’un écu est rempli d’un seul émail. Ceci m’inspira l’idée de mettre sur l’écu réservé à Champlain un champ plain d’azur dit d’azur plain en langue du blason. Son Excellence accepta avec enthousiasme cette proposition qui l’amusait beaucoup.

D’azur plein, c’est-à-dire un champ plain (ou plein) d’azur. / The expression champ plain (or plein) signifies in French blazonry that the field of a shield is filled with a single tincture.

A Fictitious Shield for Samuel de Champlain

At about mid-term as Governor General of Canada, the Right Honourable Jules Léger envisaged the possibility of creating a gallery of portraits of all the governors general from colonial times up to himself. Intensive research conducted by my colleagues and myself of the Iconography Division of the National Archives of Canada revealed that authentic portraits were missing for about two thirds of the governors for the period of New France. Léger returned with the idea of creating a panel displaying the coats of arms and the names of the governors.

My contribution to the project was to provide the artist Art Price of Ottawa with an illustration of each coat of arms and to verify the accuracy of the work once painted in colour. One problem loomed large on the horizon! Research conducted over many years had not unearthed any armorial bearings for Samuel de Champlain. In fact one event tends to confirm that he did not possess arms. On 6 May 1624, Champlain placed a stone in the foundation of his second habitation on which were engraved the arms of the king, those of Henry II, Duke of Montmorency and Viceroy of New France, as well as his own name as lieutenant of Henry II, and the date of the event (Laverdière, Œuvres de Champlain, vol. 5, pp. 1057-58). Had he possessed a coat of arms, it would have been a golden opportunity to have them engraved alongside the other two shields.

The easiest solution would have been to eliminate his name from the roll since he did not have the title of governor, although the powers he exercised could have justified such a designation. But the decision to include him was already taken. In fact his name was already engraved on the panel where the shields of arms were to be placed. A proposal was made to represent him by a fleur-de-lis, but I knew by experience that this device, if used, would eventually be reproduced as being his authentic arms. Fortunately heraldic vocabulary offered a possible solution. A champ plain (or plein) in French blazonry means that a shield is filled with a single tincture. This gave me the idea to represent Champlain with a shield filled entirely in blue, which is blazoned un champ plain d’azur or more simply put d’azur plain. His Excellency accepted with enthusiasm this proposal, which he found most amusing.

At about mid-term as Governor General of Canada, the Right Honourable Jules Léger envisaged the possibility of creating a gallery of portraits of all the governors general from colonial times up to himself. Intensive research conducted by my colleagues and myself of the Iconography Division of the National Archives of Canada revealed that authentic portraits were missing for about two thirds of the governors for the period of New France. Léger returned with the idea of creating a panel displaying the coats of arms and the names of the governors.

My contribution to the project was to provide the artist Art Price of Ottawa with an illustration of each coat of arms and to verify the accuracy of the work once painted in colour. One problem loomed large on the horizon! Research conducted over many years had not unearthed any armorial bearings for Samuel de Champlain. In fact one event tends to confirm that he did not possess arms. On 6 May 1624, Champlain placed a stone in the foundation of his second habitation on which were engraved the arms of the king, those of Henry II, Duke of Montmorency and Viceroy of New France, as well as his own name as lieutenant of Henry II, and the date of the event (Laverdière, Œuvres de Champlain, vol. 5, pp. 1057-58). Had he possessed a coat of arms, it would have been a golden opportunity to have them engraved alongside the other two shields.

The easiest solution would have been to eliminate his name from the roll since he did not have the title of governor, although the powers he exercised could have justified such a designation. But the decision to include him was already taken. In fact his name was already engraved on the panel where the shields of arms were to be placed. A proposal was made to represent him by a fleur-de-lis, but I knew by experience that this device, if used, would eventually be reproduced as being his authentic arms. Fortunately heraldic vocabulary offered a possible solution. A champ plain (or plein) in French blazonry means that a shield is filled with a single tincture. This gave me the idea to represent Champlain with a shield filled entirely in blue, which is blazoned un champ plain d’azur or more simply put d’azur plain. His Excellency accepted with enthusiasm this proposal, which he found most amusing.