Chapter VII

HERALDRY WITHIN THE SYMBOLS’ FAMILY

This is the last chapter in the trilogy art, science, symbol. Symbolism is at the apex of the triangle because it is the hidden component that gives heraldry meaning that constitutes its soul. To say that man needs symbols is a truism. They are found in all forms of religious, social or cultural manifestations and in dreams. They help gain insight into what we cannot fully understand. They help us express emotions that otherwise would require many words. They exemplify man’s desire to extend his reach, such as the primitive desire to fly like birds. They help understand opposites such as good and evil. At times the imagery found in aboriginal art forms or in the art of modern designers and artists coincides so closely with heraldry that it can be blazoned (described in heraldic language) as easily as the heraldic shield. Is this pure coincidence, or is it perhaps related to the fact that many symbols such as the sun, the cross, the circle are universal and can find expression in many types of human creations?

This chapter attempts to draw parallels between the universal world of symbols and heraldry. It strives to show that heraldry is of the same nature and works much in the same way as other symbols found around the world, that it is one of the means of expression of humanity.

1. Symbols Providing Insight

A number of concepts that cannot be fully grasped by the mind still remain important. Both zero and infinity are key mathematical concepts, although the human mind cannot fully grasp nothingness or what is limitless. In fact the human mind cannot fully grasp a very large number. A googol is a 1 followed by a 100 zeros. When written out, it seems fairly manageable, but if one starts counting 1, 2, 3, the process is virtually endless. The number of grains of sand in the world is negligible compared to this quantity. It has been estimated that a googol is larger than the number of atoms in the universe. While it is easy to speak of a 1 followed by a trillion zeros, our minds cannot begin to grasp such a large quantity, though it is not yet infinity. It seems that such unfathomable numbers have no counterpart in the concrete, something that would make them more symbolic than real as far as any practical applications are concerned. Still, the two extremes of nothingness and infinity have preoccupied mathematicians, philosophers and religious thinkers since Antiquity.

Symbolic imagery can help link these abstract notions to a visible, tangible reality. For instance, a circle that is without a starting or ending point can illustrate the idea that something can have no beginning nor end as does eternity. However, if we magnify a circle drawn with pencil on paper, we see a series of spots with spaces in-between. We then realize that the drawn circle is not a perfect symbol because it is not even continuous. If we then close our eyes we can see in our mind a circle with an imaginary line that is not material anymore. In other words, the circular line that is drawn imperfectly in reality represented in the mind becomes an abstract and pure form. No one can imagine a circle without some form of defining line no matter how fine, but it seems obvious that a circle exists first as an idea that can be represented by a material line. Of course the imagery does not offer a full understanding of the idea of an eternity without beginning or end, but it does make us envisage that such things can exist beyond the imperfections of the material world.

The Mobius strip also represents a continuous line and therefore eternity. To illustrate its properties, cut two strips of paper from a white sheet and mark one side of each with a black marker. If you join one strip to form an ordinary circle or wheel, you will find that your finger can move continually on the outside or on the inside of the circle, but cannot go from the inside to the outside without interruption. If you then take the second strip of paper and give one end an 180o twist so that the white side joins with the side marked black, you will find that you can move your finger without any break on both the white and black sides of the strip. It is little wonder that the infinity symbol takes the form of a Mobius strip (fig. 1).

Fig. 1 A Mobius strip granted as a badge to Arthur Drysdale Stairs of Halifax in 1964. From Beddoe’s Canadian Heraldry (1981), 149 no. 249, see also 135 no. 221 and 137.

This notion of the material symbolically representing the abstract seems even better illustrated if we draw a circle, mark the centre with a dot, and then completely erase it. Though we no longer have a central dot, we are still sure that there is a centre somewhere within that circle and we cannot picture that centre in our minds without a dot. But how large should the dot be? The smaller it is, the better it represents the centre. But does it not become so small as to disappear into nothingness, into pure abstraction? Again a graphic image symbolizes in a concrete and imperfect way an idea that seems pure or perfect in its abstract form. Such notions, though given imperfect expression remain extremely important in our daily lives. The wheel is an imperfect circle with an imperfect center, and yet the modern world cannot do without it.

Numerous striking symbols exist. As a youth, I was taught that a mystery was a truth that we cannot understand, but that we must believe in because revealed by God. One of the mysteries I occasionally pondered over was that of the Holy Trinity, one God comprising three persons: the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost. One day in school, a priest lit three matches that he held separately then brought together to create a single flame. I knew that he had not fully explained the Trinity, but the impact was powerful and I thought he had come as close as one could to an explanation. I was truly convinced that the symbolism of three flames becoming one had provided me with a great insight into this mystery. If material flames could be both three and one, I reasoned that such ethereal entities as compose the Holy Trinity could surely have similar properties.

Many symbols have strong emotional content. To convey a rather complex notion such as patriotism, some speak at length or write page upon page with passionate fervour. Yet the scene of a soldier in uniform intently saluting his country’s flag somehow expresses the same idea with far more power. The imagery of the saluting soldier arouses in most people emotions similar to those felt by the soldier as he salutes. There is empathy or resonance between the viewer and the symbolic gesture even if the viewer has never performed the saluting ceremony.

Symbols can also express powers or situations we strive for and frequently achieve in the future. In the past, dragons breathing out smoke and fire were viewed as having great destructive force. Today flame-throwing vehicles and bombers create greater and more threatening fires than the mythical dragon. Likewise modern jets surely can fly faster than the tiny wings on the cap and sandals of Mercury, the frail wax and feather wings of Icarus or the wings we imagine for angels. In other words, the powers of such mythical creatures that first exist in man’s mind are equalled or surpassed by man’s technical genius.

Symbols often express duality or opposites. A very good example is the Chinese Yang-Yin whose black and white segments illustrate both opposing and complementary forces with a centre as a kind of neutral zone in-between. In fact good cannot be understood without evil as its counterpart. Justice is likewise understood in the face of injustice, beauty in comparison with ugliness.

We find in symbols timeless concepts such as love, justice or courage. Heraldic symbols often honour the past such as the four quarters in the arms of Canada honouring the founding nations. They also can express hope for the future, such as the Christian cross as a symbol of redemption and salvation. The passage of time is symbolically illustrated by the hourglass, the sand at the bottom representing the past, that on top the future, and the aperture through which it flows, the fleeting present. It is in fact much easier to grasp the idea of past and future than that of present which again raises the questions: How long does the present last? Does it exist at all?

Within the universal realm of symbols, heraldry responds to both practical needs and more human ones such as the desire for meaning, beauty and order. The beauty and precision of its ancient language and the impact of its bright colours and well-balanced proportions fascinate heraldry students. When receiving a grant of arms, some recipients are moved to tears by the striking beauty of the finished art and the permanent symbolic value it represents for them and their family. Heraldry gives new meaning and life to ancient symbols and brings into its fold more contemporary notions expressed with old or new imagery. The rules that govern this art and science are specifically designed to create something of beauty that is unique and quickly recognizable at a distance: just as well on a passing municipal vehicle in modern times as on the shield of the mounted knight at full gallop in former days.

2. The Dynamic Nature of Symbols

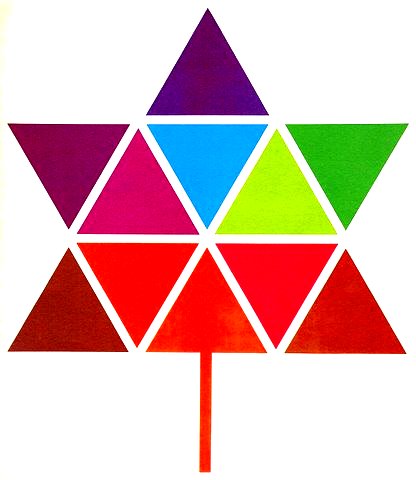

To say that symbols symbolize sounds redundant, but the verb does convey the idea of an interaction between something visible and a spectator. Indeed, to remain alive and strong, symbols must not leave the spectator indifferent. They have to impart meaning and arouse emotions, the type of emotion induced in the presence of something significant but retaining an aura of mystery. A symbol always refers to something greater and more complex than the image that represents it. Saying that the maple leaf is the symbol of Canada creates a link between a concrete palpable object and a far larger and more diversified phenomenon called Canada. There are many reasons behind this symbolization, beginning with the observable fact that the colourful leaves in autumn are a striking feature of the landscape. The maple leaf can also represent the First Nations as first occupants of the land and the first makers of maple syrup. It became the symbol of a cause when, during the Rebellions of 1837-38, it appeared on the recruitment certificates of Patriots in Upper Canada and, as a maple branch, on the rebels’ flag at St. Eustache, Lower Canada, to signify opposition to the established order. Likewise the maple leaf embraces a cause larger than its mere physical image as part of the many regimental badges of the Canadian Expeditionary Force during the First World War (http://www.britishbadgeforum.com/canadian_expeditionary_force/cef_cap_badge_index3.htm) and as a sprig of three red maple leaves on the Battle Flag of Canada deployed on the battle fields of Europe during the Second World War, from 1939 to 1944 (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1250&ProjectElementID=4672). When the maple leaf represents Canada as a huge and diversified country from sea to sea, it is then a small thing representing the many facets of a large, diversified, and complex entity that encompasses the maple leaf itself. It is in the nature of symbols to represent larger and more complex realities than themselves such as the depiction of an atom symbolizing all matter and life.

Usually symbols represent things that are not only more complex, but more abstract than what they are in concrete or depicted form. Good examples of this are the many symbols of love, whether it be a rose, a heart, cupid’s arrow, a dove, a swan, the goddess of love and beauty Aphrodite (root of the word aphrodisiac), or the god of love Eros (root of erotic) and his mate Psyche (personification of the soul). Concepts like love or infinity cannot be fully grasped. They cannot be boxed in because they have no defined limits. Love is complex and intangible; it is dynamic and pulsating; it waxes and wanes; it grows and withers.

Symbols are often at odds with conventional logic since such elements as beauty, appearance and appeal usually take precedence over more rational considerations. The red stylized heart presents a friendly appealing image and, while it is true that at times love does affect the heart by making it pump faster, this rarely results in a heart attack. When logic prevails, one cannot escape the fact that love affects the brain far more than it does the heart. It can make a person do great things such as acts of courage or generosity, writing beautiful poetry, or painting masterpieces. Conversely it can also make the affected mind do the most idiotic things, a subject upon which there is no need to elaborate.

Though an arrow through the brain to depict love would be far more appropriate, rationally, than an arrow through the heart, piercing the organ where reasoning and all the body functions are located seems most unappealing. Undeniably an arrow through the organ that is traditionally seen as the seat of emotions is more readily accepted as a friendlier, cosier image. The French thinker Blaise Pascal put this in a nutshell with the phrase “Le cœur a ses raisons que la raison ne connaît pas” (The heart has its reason of which reason knows nothing). It has become a truism that force, persecution or war cannot destroy ideology. Is it because man is such a rational creature that ideas make an indelible impression on his mind? I don’t believe so! What seems more probable is that all powerful ideas mutate into symbols with a strong emotional component that make them invincible. The motto of the French Republic “ Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité” or those of the American Revolution “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death” and “Don’t Tread on Me” are not just ideological; they act as symbols that appeal just as much to the emotions as to the mind.

Heraldic symbols often create strong emotions in connection with a sense of identity, of belonging to an ethnic or cultural group called a nation. One powerful modern manifestation where humans become most intimately connected with the symbolism of heraldry is the practice of painting national flags over one’s face at important sport events or national celebrations. Here humans use the ancient practice of body painting as a means of achieving complete identification with their national emblem. When the Greeks defeated the Czechs during the 2004 Euro soccer tournament, a fan was seen with arms outstretched over his head bowing over the flag of Greece. This worshipful gesture again conveyed a powerful image of complete identification with the national flag, with all the symbolism it contains, with all the emotions it arouses. Many similar powerful endorsements of national flags such as wearing them as articles of clothing are encountered at popular events, and it is perhaps within these circles of joy and enthusiasm that heraldry finds some of its most poignant manifestations, even though such manifestations can be viewed by some as encroaching upon the dignity of national emblems.

3. Universal Ideas and Themes

One of the aspects of heraldry that takes it beyond the realm of boast, pomp and human vanity is its ability to express universal ideas. The recurrent themes of rebirth or renaissance and its corollary immortality are powerfully expressed by the phoenix’s ability to be reborn from its ashes after burning on a pyre. Like many symbols, the phoenix is older than heraldry and not exclusive to it, but it is in the nature of symbols not to be exclusive to one domain. The symbolism of the phoenix has been applied to the Canadian Parliament Buildings destroyed by fire in 1916 and rebuilt in their present form. The great phoenix of the 21st century may well be the World Trade Centre whose towers long stood on the New York horizon as a symbol of man’s ingenuity. With their explosive destruction, they came to represent Western values and Western civilization being attacked and threatened. But a new tower has risen on the same site as a symbol of the collective will not to let evil forces prevail. The meanings attached to the towers are a good example of how symbols evolve and are fashioned by the collective consciousness.

The idea of death and rebirth is also associated with the sun that dies out at night and is reborn in the morning. The ultimate symbol of death and resurrection in Christian symbolism is Christ rising from his tomb. The arms of the Scottish Town of Inverness displays Christ on the cross, though some feel it is inappropriate to place the figure of Christ on a shield (http://www.ngw.nl/heraldrywiki/index.php?title=Inverness). Representing Christ’s resurrection and triumph over death with the “glory cross”, a Latin cross with rays emanating between its branches, conveys the same notion of resurrection in a reinforced way. In religious symbolism, an eight-pointed star is said to represent regeneration. [1]

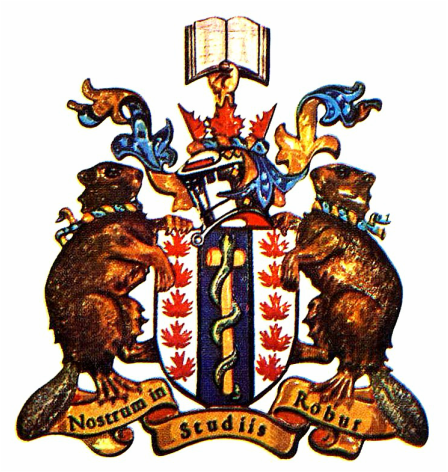

Similarly the sun’s rays can symbolize curative powers and, in fact, they can have curative properties in reality. A strong symbol of regeneration that found its way on the heraldic shield is the serpent entwining the rod of Aesculapius to symbolize healing, wisdom and knowledge (fig. 2-3). This rejuvenating power seems to come from the serpent’s ability to shed its skin and assume a new life. Of course a number of animals have similar abilities, such as the lobster that sheds its carapace and the frog or salamander that can grow new limbs.

Numerous striking symbols exist. As a youth, I was taught that a mystery was a truth that we cannot understand, but that we must believe in because revealed by God. One of the mysteries I occasionally pondered over was that of the Holy Trinity, one God comprising three persons: the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost. One day in school, a priest lit three matches that he held separately then brought together to create a single flame. I knew that he had not fully explained the Trinity, but the impact was powerful and I thought he had come as close as one could to an explanation. I was truly convinced that the symbolism of three flames becoming one had provided me with a great insight into this mystery. If material flames could be both three and one, I reasoned that such ethereal entities as compose the Holy Trinity could surely have similar properties.

Many symbols have strong emotional content. To convey a rather complex notion such as patriotism, some speak at length or write page upon page with passionate fervour. Yet the scene of a soldier in uniform intently saluting his country’s flag somehow expresses the same idea with far more power. The imagery of the saluting soldier arouses in most people emotions similar to those felt by the soldier as he salutes. There is empathy or resonance between the viewer and the symbolic gesture even if the viewer has never performed the saluting ceremony.

Symbols can also express powers or situations we strive for and frequently achieve in the future. In the past, dragons breathing out smoke and fire were viewed as having great destructive force. Today flame-throwing vehicles and bombers create greater and more threatening fires than the mythical dragon. Likewise modern jets surely can fly faster than the tiny wings on the cap and sandals of Mercury, the frail wax and feather wings of Icarus or the wings we imagine for angels. In other words, the powers of such mythical creatures that first exist in man’s mind are equalled or surpassed by man’s technical genius.

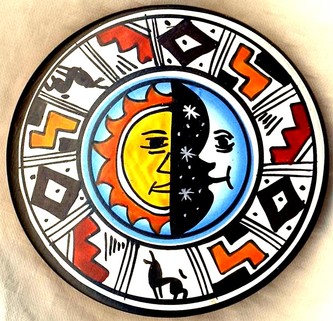

Symbols often express duality or opposites. A very good example is the Chinese Yang-Yin whose black and white segments illustrate both opposing and complementary forces with a centre as a kind of neutral zone in-between. In fact good cannot be understood without evil as its counterpart. Justice is likewise understood in the face of injustice, beauty in comparison with ugliness.

We find in symbols timeless concepts such as love, justice or courage. Heraldic symbols often honour the past such as the four quarters in the arms of Canada honouring the founding nations. They also can express hope for the future, such as the Christian cross as a symbol of redemption and salvation. The passage of time is symbolically illustrated by the hourglass, the sand at the bottom representing the past, that on top the future, and the aperture through which it flows, the fleeting present. It is in fact much easier to grasp the idea of past and future than that of present which again raises the questions: How long does the present last? Does it exist at all?

Within the universal realm of symbols, heraldry responds to both practical needs and more human ones such as the desire for meaning, beauty and order. The beauty and precision of its ancient language and the impact of its bright colours and well-balanced proportions fascinate heraldry students. When receiving a grant of arms, some recipients are moved to tears by the striking beauty of the finished art and the permanent symbolic value it represents for them and their family. Heraldry gives new meaning and life to ancient symbols and brings into its fold more contemporary notions expressed with old or new imagery. The rules that govern this art and science are specifically designed to create something of beauty that is unique and quickly recognizable at a distance: just as well on a passing municipal vehicle in modern times as on the shield of the mounted knight at full gallop in former days.

2. The Dynamic Nature of Symbols

To say that symbols symbolize sounds redundant, but the verb does convey the idea of an interaction between something visible and a spectator. Indeed, to remain alive and strong, symbols must not leave the spectator indifferent. They have to impart meaning and arouse emotions, the type of emotion induced in the presence of something significant but retaining an aura of mystery. A symbol always refers to something greater and more complex than the image that represents it. Saying that the maple leaf is the symbol of Canada creates a link between a concrete palpable object and a far larger and more diversified phenomenon called Canada. There are many reasons behind this symbolization, beginning with the observable fact that the colourful leaves in autumn are a striking feature of the landscape. The maple leaf can also represent the First Nations as first occupants of the land and the first makers of maple syrup. It became the symbol of a cause when, during the Rebellions of 1837-38, it appeared on the recruitment certificates of Patriots in Upper Canada and, as a maple branch, on the rebels’ flag at St. Eustache, Lower Canada, to signify opposition to the established order. Likewise the maple leaf embraces a cause larger than its mere physical image as part of the many regimental badges of the Canadian Expeditionary Force during the First World War (http://www.britishbadgeforum.com/canadian_expeditionary_force/cef_cap_badge_index3.htm) and as a sprig of three red maple leaves on the Battle Flag of Canada deployed on the battle fields of Europe during the Second World War, from 1939 to 1944 (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1250&ProjectElementID=4672). When the maple leaf represents Canada as a huge and diversified country from sea to sea, it is then a small thing representing the many facets of a large, diversified, and complex entity that encompasses the maple leaf itself. It is in the nature of symbols to represent larger and more complex realities than themselves such as the depiction of an atom symbolizing all matter and life.

Usually symbols represent things that are not only more complex, but more abstract than what they are in concrete or depicted form. Good examples of this are the many symbols of love, whether it be a rose, a heart, cupid’s arrow, a dove, a swan, the goddess of love and beauty Aphrodite (root of the word aphrodisiac), or the god of love Eros (root of erotic) and his mate Psyche (personification of the soul). Concepts like love or infinity cannot be fully grasped. They cannot be boxed in because they have no defined limits. Love is complex and intangible; it is dynamic and pulsating; it waxes and wanes; it grows and withers.

Symbols are often at odds with conventional logic since such elements as beauty, appearance and appeal usually take precedence over more rational considerations. The red stylized heart presents a friendly appealing image and, while it is true that at times love does affect the heart by making it pump faster, this rarely results in a heart attack. When logic prevails, one cannot escape the fact that love affects the brain far more than it does the heart. It can make a person do great things such as acts of courage or generosity, writing beautiful poetry, or painting masterpieces. Conversely it can also make the affected mind do the most idiotic things, a subject upon which there is no need to elaborate.

Though an arrow through the brain to depict love would be far more appropriate, rationally, than an arrow through the heart, piercing the organ where reasoning and all the body functions are located seems most unappealing. Undeniably an arrow through the organ that is traditionally seen as the seat of emotions is more readily accepted as a friendlier, cosier image. The French thinker Blaise Pascal put this in a nutshell with the phrase “Le cœur a ses raisons que la raison ne connaît pas” (The heart has its reason of which reason knows nothing). It has become a truism that force, persecution or war cannot destroy ideology. Is it because man is such a rational creature that ideas make an indelible impression on his mind? I don’t believe so! What seems more probable is that all powerful ideas mutate into symbols with a strong emotional component that make them invincible. The motto of the French Republic “ Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité” or those of the American Revolution “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death” and “Don’t Tread on Me” are not just ideological; they act as symbols that appeal just as much to the emotions as to the mind.

Heraldic symbols often create strong emotions in connection with a sense of identity, of belonging to an ethnic or cultural group called a nation. One powerful modern manifestation where humans become most intimately connected with the symbolism of heraldry is the practice of painting national flags over one’s face at important sport events or national celebrations. Here humans use the ancient practice of body painting as a means of achieving complete identification with their national emblem. When the Greeks defeated the Czechs during the 2004 Euro soccer tournament, a fan was seen with arms outstretched over his head bowing over the flag of Greece. This worshipful gesture again conveyed a powerful image of complete identification with the national flag, with all the symbolism it contains, with all the emotions it arouses. Many similar powerful endorsements of national flags such as wearing them as articles of clothing are encountered at popular events, and it is perhaps within these circles of joy and enthusiasm that heraldry finds some of its most poignant manifestations, even though such manifestations can be viewed by some as encroaching upon the dignity of national emblems.

3. Universal Ideas and Themes

One of the aspects of heraldry that takes it beyond the realm of boast, pomp and human vanity is its ability to express universal ideas. The recurrent themes of rebirth or renaissance and its corollary immortality are powerfully expressed by the phoenix’s ability to be reborn from its ashes after burning on a pyre. Like many symbols, the phoenix is older than heraldry and not exclusive to it, but it is in the nature of symbols not to be exclusive to one domain. The symbolism of the phoenix has been applied to the Canadian Parliament Buildings destroyed by fire in 1916 and rebuilt in their present form. The great phoenix of the 21st century may well be the World Trade Centre whose towers long stood on the New York horizon as a symbol of man’s ingenuity. With their explosive destruction, they came to represent Western values and Western civilization being attacked and threatened. But a new tower has risen on the same site as a symbol of the collective will not to let evil forces prevail. The meanings attached to the towers are a good example of how symbols evolve and are fashioned by the collective consciousness.

The idea of death and rebirth is also associated with the sun that dies out at night and is reborn in the morning. The ultimate symbol of death and resurrection in Christian symbolism is Christ rising from his tomb. The arms of the Scottish Town of Inverness displays Christ on the cross, though some feel it is inappropriate to place the figure of Christ on a shield (http://www.ngw.nl/heraldrywiki/index.php?title=Inverness). Representing Christ’s resurrection and triumph over death with the “glory cross”, a Latin cross with rays emanating between its branches, conveys the same notion of resurrection in a reinforced way. In religious symbolism, an eight-pointed star is said to represent regeneration. [1]

Similarly the sun’s rays can symbolize curative powers and, in fact, they can have curative properties in reality. A strong symbol of regeneration that found its way on the heraldic shield is the serpent entwining the rod of Aesculapius to symbolize healing, wisdom and knowledge (fig. 2-3). This rejuvenating power seems to come from the serpent’s ability to shed its skin and assume a new life. Of course a number of animals have similar abilities, such as the lobster that sheds its carapace and the frog or salamander that can grow new limbs.

The arms granted the College of Family Physicians of Canada / Collège des médecins de famille du Canada by Kings of Arms of England in 1977 (fig. 2) display an interesting variation upon the rod of Aesculapius in that the serpent entwines the handle of a gavel. Such a gavel was in fact presented by Dr. T.C. Routley at the college’s founding meeting in 1954. The same gavel is repeated in the arms granted by the English Kings of Arms to Dr. Donald W. Rae in 1978 honouring his term as president of the college (fig. 3). Illustrations from Beddoe’s Canadian Heraldry (1981): 134, no. 214; 115, no. 181. See also Heraldry in Canada / L’Héraldique au Canada11, no. 4 (December 1977): 2-5 and 13, no. 3 (September 1979), 24.

Hope remained at the bottom of Pandora’s Box as the last resort when everything else had escaped. But hope’s most frequent heraldic symbol is the dove with an olive branch in its beak referring to the dove that Noah sent out, and which returned with an olive branch (a leaf in some versions) indicating that the land was producing again after the deluge. Noah’s arc itself is a strong symbol of weathering the storm against extreme difficulties, of preserving and renewing life after a cataclysm. Another heraldic symbol of hope is the anchor that can represent the only instrument of survival for sailors in a threatening storm. The same idea appears figuratively in the Bible: “Which hope we have as an anchor of the soul…” (Hebrews 6: 19).

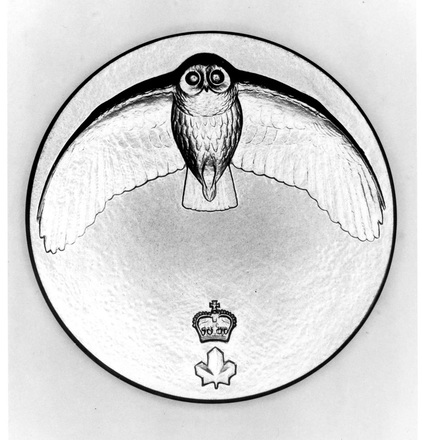

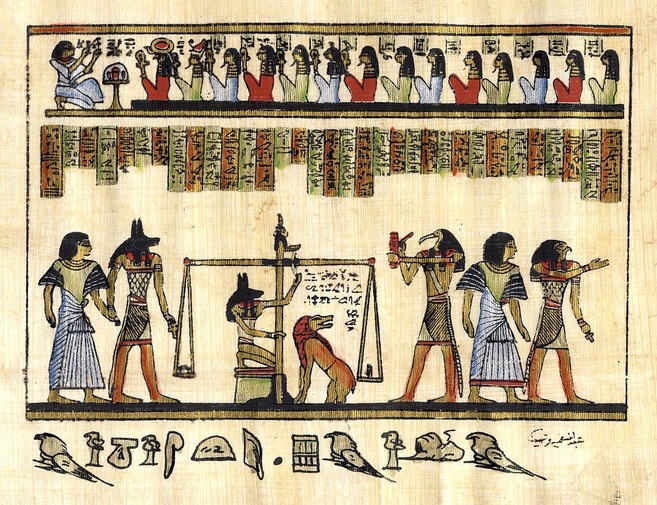

Scales are frequently used to express justice because justice requires the careful weighing of facts and testimonies to arrive at an equitable balanced judgement. In ancient Egypt, they were symbolic of the ultimate judgement at life’s end (fig. 7). The antique lamp is a frequent symbol of learning since it allows reading far into the night, and its persistent flame can also symbolize illumination of the mind. The seal of Governor General Jules Léger, later granted as a coat of arms to his descendents by the Canadian Heraldic Authority, displays an owl with expanded wings placed above the crown: http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1865&ProjectElementID=6303. The obvious symbolism is that the monarchy, which is a human institution of great dignity, must also be guided and protected by the superior force of wisdom (fig. 4).

Scales are frequently used to express justice because justice requires the careful weighing of facts and testimonies to arrive at an equitable balanced judgement. In ancient Egypt, they were symbolic of the ultimate judgement at life’s end (fig. 7). The antique lamp is a frequent symbol of learning since it allows reading far into the night, and its persistent flame can also symbolize illumination of the mind. The seal of Governor General Jules Léger, later granted as a coat of arms to his descendents by the Canadian Heraldic Authority, displays an owl with expanded wings placed above the crown: http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1865&ProjectElementID=6303. The obvious symbolism is that the monarchy, which is a human institution of great dignity, must also be guided and protected by the superior force of wisdom (fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Jules Léger’s privy seal as 21st Governor General of Canada. As a constitutional monarchy, Canada is represented by the crown above a maple leaf over which the owl with extended wings appears as the protective force of wisdom. Library and Archives Canada, photo C 98879.

Some intellectuals in the Middle Ages viewed man as a microcosm reflecting or embodying in miniature form the greater universe. Certainly mankind possesses the desire to conquer the universe and know its secrets, but humans also need at times to find refuge in more friendly and closed surroundings, perhaps in their home or a country cottage. After fixing the troubles of the Roman Republic, General Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus went back to ploughing his fields. After Desert Storm, General Norman Schwarzkopf sought the friendlier and cosier world of fly-fishing. The space ship Enterprise exemplifies these two needs quite well. After facing formidable dangers, the crew finds safety within the more friendly and relaxing confines of the spaceship. Heraldry in a sense also reflects man’s need for these two poles of being. Symbols always reflect realities greater than themselves, and in heraldic art, man’s most outstanding exploits are recorded symbolically within the friendly and manageable confines of the shield.

4. Archetypes

Man displays physical remnants of his evolutionary past such as vestiges of a tailbone in the foetus and traces of gills at the embryonic stage that point to a remote aquatic origin. Jungian psychology speculates that man also retains certain archaic mental remnants of which he is unaware at a conscious level and that predate individual existence. This ancient mental inheritance manifests itself in such areas as dreams, myths, folklore, fairy tales, and rituals.

Such manifestations termed archetypes are sufficiently similar in nature to be recognized as a variation upon a same theme. Such patterns of imagery or behaviour are common to all men and embedded in all men’s psyche no matter the age or cultural background. The primeval mind from which they emanate has been termed the collective unconscious. Archetypal dreams do not deal with ordinary occurrences, but with unusual scenes that may involve the planets, such basic elements as earth, fire and water, finding hidden treasures or temples. Archetypes find a deep-rooted resonance in man, stir up strong emotions and contain symbolic messages. It is little wonder that they have found their way unto the heraldic shield.

The already mentioned phoenix expresses the archetypal idea of death and rebirth and its corollary immortality. In fact the French heraldic word for the flames from which it rises is immortalité. The salamander that breathes flames and thrives in fire, with the motto J’y vis et je l’éteins (I live in it and put it out), was the badge of Francis I of France and is today found in the arms of the French municipalities of Fontainebleau and Le Havre and in the arms of families such as the Earls of Douglas. In Canada the supporters of the arms of the Fédération des francophones de Terre-Neuve et du Labrador are two blue salamanders to symbolize the enduring nature of the federation, its strength and long-term commitment (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=481&ProjectElementID=1613). The mastery of fire is double-edged. The salamander is a symbol of alchemy where fire becomes a creative force, as it does also in the forges of the god Vulcan. Conversely the fiery salamander parallels a more modern reptilian monster named Godzilla seen breathing fire as it moves through an enflamed city, thus symbolizing the destructive side of fire.

Fire is a symbol of burning love, zeal or passion. A burning torch in the arms attributed to St. Dorothy exemplifies the zeal of her faith. Torches and beacons often appear in coats of arms to represent the light that illuminates or shows the way. If you search the Public Register of Arms, Flags and Badges of Canada under the words flame, fire or torch under both Main Charge and Attribute, you will find a huge number of coats of arms associated with fire. Fire is often opposed to ice as in Robert Frost poem “Fire and Ice” where he debates whether the world will be destroyed by fire or ice.

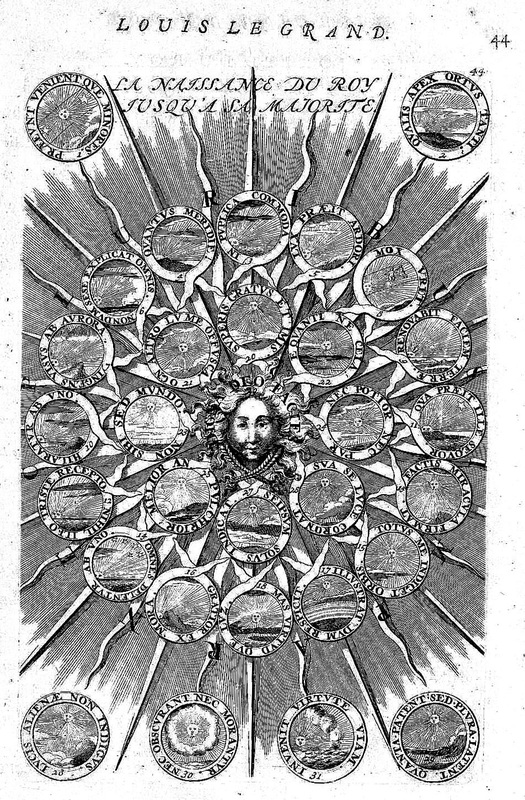

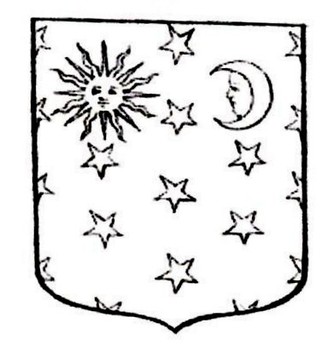

Radiant stars and suns are frequent as symbols of guidance, of illumination or the diffusion of good deeds and knowledge. The Imperial Society of Knights Bachelor whose charitable objectives are the relief of poverty, the advancement of education, supporting hospitals, aiding the elderly and needy, as well as the promotion of understanding and cooperation among citizens of the Commonwealth includes a sword enfiling (going through) a coronet and placed over a large sun. This idea is echoed in the popular notion of “bringing sunshine into others’ life” and the more recent Liberal 2015 election slogan “sunny ways” coined by the Canadian Prime Minister, Laurier in the 1890s. The radiant sun with a face adopted as an emblem by Louis XIVth was meant to symbolize his sovereign power and to indicate that he viewed himself as matchless among kings; but it also conveyed the notion of a brilliant and enlightened reign in spiritual, intellectual, and material domains (fig. 5).

4. Archetypes

Man displays physical remnants of his evolutionary past such as vestiges of a tailbone in the foetus and traces of gills at the embryonic stage that point to a remote aquatic origin. Jungian psychology speculates that man also retains certain archaic mental remnants of which he is unaware at a conscious level and that predate individual existence. This ancient mental inheritance manifests itself in such areas as dreams, myths, folklore, fairy tales, and rituals.

Such manifestations termed archetypes are sufficiently similar in nature to be recognized as a variation upon a same theme. Such patterns of imagery or behaviour are common to all men and embedded in all men’s psyche no matter the age or cultural background. The primeval mind from which they emanate has been termed the collective unconscious. Archetypal dreams do not deal with ordinary occurrences, but with unusual scenes that may involve the planets, such basic elements as earth, fire and water, finding hidden treasures or temples. Archetypes find a deep-rooted resonance in man, stir up strong emotions and contain symbolic messages. It is little wonder that they have found their way unto the heraldic shield.

The already mentioned phoenix expresses the archetypal idea of death and rebirth and its corollary immortality. In fact the French heraldic word for the flames from which it rises is immortalité. The salamander that breathes flames and thrives in fire, with the motto J’y vis et je l’éteins (I live in it and put it out), was the badge of Francis I of France and is today found in the arms of the French municipalities of Fontainebleau and Le Havre and in the arms of families such as the Earls of Douglas. In Canada the supporters of the arms of the Fédération des francophones de Terre-Neuve et du Labrador are two blue salamanders to symbolize the enduring nature of the federation, its strength and long-term commitment (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=481&ProjectElementID=1613). The mastery of fire is double-edged. The salamander is a symbol of alchemy where fire becomes a creative force, as it does also in the forges of the god Vulcan. Conversely the fiery salamander parallels a more modern reptilian monster named Godzilla seen breathing fire as it moves through an enflamed city, thus symbolizing the destructive side of fire.

Fire is a symbol of burning love, zeal or passion. A burning torch in the arms attributed to St. Dorothy exemplifies the zeal of her faith. Torches and beacons often appear in coats of arms to represent the light that illuminates or shows the way. If you search the Public Register of Arms, Flags and Badges of Canada under the words flame, fire or torch under both Main Charge and Attribute, you will find a huge number of coats of arms associated with fire. Fire is often opposed to ice as in Robert Frost poem “Fire and Ice” where he debates whether the world will be destroyed by fire or ice.

Radiant stars and suns are frequent as symbols of guidance, of illumination or the diffusion of good deeds and knowledge. The Imperial Society of Knights Bachelor whose charitable objectives are the relief of poverty, the advancement of education, supporting hospitals, aiding the elderly and needy, as well as the promotion of understanding and cooperation among citizens of the Commonwealth includes a sword enfiling (going through) a coronet and placed over a large sun. This idea is echoed in the popular notion of “bringing sunshine into others’ life” and the more recent Liberal 2015 election slogan “sunny ways” coined by the Canadian Prime Minister, Laurier in the 1890s. The radiant sun with a face adopted as an emblem by Louis XIVth was meant to symbolize his sovereign power and to indicate that he viewed himself as matchless among kings; but it also conveyed the notion of a brilliant and enlightened reign in spiritual, intellectual, and material domains (fig. 5).

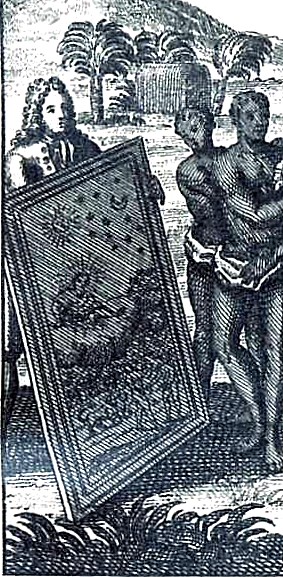

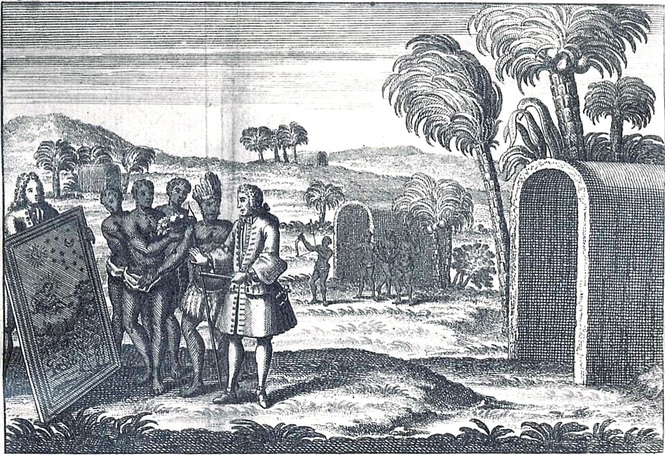

Fig. 5 Engraving entitled “La naissance du roy jusqu’à sa majorité” showing the Sun King Louis XIV surrounded by sun rays and his badges. Around the king’s head is the motto Digna deo facies which is translated as “He is like the God of this visible world.” From Histoire du roy Louis le Grand par les medailles, emblêmes, devises, jettons, inscriptions, armoiries, et autres monumens publics. Recuëillis, et expliquéz par le pere Claude Francois Menestrier de la compagnie de Iesus (Paris: I. B. Nolin, 1692): 44. Although the best known motto of Louis XIV is Nec pluribus impar (Not equalled by many), he had over 150 mottos according to Menestrier.

In his hymn to Aton the sun god, Akhenaton pictures the sun as the ultimate life-giving force that dissipates darkness and ensures the well being of all creatures. The notion of light conquering darkness is part of every civilization. In heraldry, the same idea is contained in a device called a sunburst, consisting of sunrays bursting forth from behind a cloud as a symbol of hope or better weather ahead. Light is also a symbol of spiritual illumination, or the acquisition of knowledge. The arms attributed to St. Bede, author of the first ecclesiastical history of England, contain a pitcher on a blue field and a gold sun emanating from the top of the shield to signify divine light or inspiration. The arms attributed to the great philosopher and theologian St. Thomas Aquinas display a sun in splendour with an eye in the centre to represent the divine inspiration received while writing his works. [2] My own arms represent the same notions: “The gold suns set against a black background symbolize the quest for wisdom and truth in the sometimes dark times in which we live. In universal terms, this can be seen in the eternal combat between good and evil, between positive and negative – a battle that has confronted man since his existence.” (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=212&ShowAll=1)

One archetypal image frequently appearing in heraldry is the triumph of good over evil, which is akin to light conquering darkness. A shield divided into black and white would express this in the best heraldic tradition, but good versus evil usually takes the shape of the hero or demi-god triumphing over some nefarious force. The best known such hero may well be St. George on horseback slaying a dragon. It features on the badge of the Order of St. Michael and St. George, on the shield of the City of Moscow and in the arms of a number of families such as Czertwertynski, Glasenapp, Joerg and Saint-George. A rather poignant version of the same theme is found in the crest of Robert Ratclyffe, Earl of Sussex, showing a forearm with the hand choking a dragon. Another popular slayer of demons is the archangel Michael displayed on the arms of Arkhangelsk (Russia), Brussels (Belgium), Jena (Germany), San Miguel de Allende (Mexico) and those of families such as Michael, Michel, Saint-Michel, van Schorel, and Sistrières.

Sometimes the struggle between good and evil takes the form of a David and Goliath encounter. The two hands in the city of Antwerp allude to the giant Druon Antigonus who harassed the region until slain by the hero Salvius Barbo who cut off the giant’s hands and threw him in the river Schelde. The name of the city is derived from the Flemish for hand-throwing, “hand-werpen”. The five red roundels on the arms of the Medicis according to one interpretation also recall a David-Goliath event. One of the ancestors, Evrard de Medicis, while fighting with Charlemagne against the Lombards, was confronted by a giant called Mugel holding a huge club from which depended five drops of blood. Evrard bravely countered a blow from Mugel causing the five drops of blood to fly from the club unto his shield. Another less dramatic interpretation is that the red roundels or balls on the Medici shield represent pills referring to the medical profession. In Italian, Medici is the plural of medico, which means a medical doctor.

The arms of the Visconti family display a serpent devouring a child, the archetypal theme of the devouring monster found in the account of Jonas and the whale. The same theme is recorded on the shield of Tarascon-sur-Rhône wherein a sort of dragon (tarasque) is seen devouring a man. In Fairbairn’s Crests of the Families of Great Britain and Ireland, the crest of Sanderson of Lincolnshire is described as: A wolf’s head Sable devouring a man proper, the body, from the small of the back downward, hanging out of his mouth. A truly poignant image along the same theme is Francisco de Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturn_Devouring_His_Son).

Another powerful archetype found in heraldry is the pelican in its piety, that is to say the pelican wounding itself at the breast with its beak to feed its young with its own blood. This image dramatically exemplifies maternal sacrifice and, in a broader context, self-sacrifice for the sake of others (fig. 6). The pelican’s act parallels our own practice of donating blood for transfusions that save lives. Blood shedding is universally considered a symbol of courage and sacrifice. It is ultimately reminiscent of the blood of the lamb, of the crucifixion of Jesus for the sake of humanity. Archetypes always seem to have their opposites, which in this case would be blood taking to kill or for nourishment as in the case of some bats, mosquitoes, leeches, the legendary vampire, and the more modern chupacabra.

One archetypal image frequently appearing in heraldry is the triumph of good over evil, which is akin to light conquering darkness. A shield divided into black and white would express this in the best heraldic tradition, but good versus evil usually takes the shape of the hero or demi-god triumphing over some nefarious force. The best known such hero may well be St. George on horseback slaying a dragon. It features on the badge of the Order of St. Michael and St. George, on the shield of the City of Moscow and in the arms of a number of families such as Czertwertynski, Glasenapp, Joerg and Saint-George. A rather poignant version of the same theme is found in the crest of Robert Ratclyffe, Earl of Sussex, showing a forearm with the hand choking a dragon. Another popular slayer of demons is the archangel Michael displayed on the arms of Arkhangelsk (Russia), Brussels (Belgium), Jena (Germany), San Miguel de Allende (Mexico) and those of families such as Michael, Michel, Saint-Michel, van Schorel, and Sistrières.

Sometimes the struggle between good and evil takes the form of a David and Goliath encounter. The two hands in the city of Antwerp allude to the giant Druon Antigonus who harassed the region until slain by the hero Salvius Barbo who cut off the giant’s hands and threw him in the river Schelde. The name of the city is derived from the Flemish for hand-throwing, “hand-werpen”. The five red roundels on the arms of the Medicis according to one interpretation also recall a David-Goliath event. One of the ancestors, Evrard de Medicis, while fighting with Charlemagne against the Lombards, was confronted by a giant called Mugel holding a huge club from which depended five drops of blood. Evrard bravely countered a blow from Mugel causing the five drops of blood to fly from the club unto his shield. Another less dramatic interpretation is that the red roundels or balls on the Medici shield represent pills referring to the medical profession. In Italian, Medici is the plural of medico, which means a medical doctor.

The arms of the Visconti family display a serpent devouring a child, the archetypal theme of the devouring monster found in the account of Jonas and the whale. The same theme is recorded on the shield of Tarascon-sur-Rhône wherein a sort of dragon (tarasque) is seen devouring a man. In Fairbairn’s Crests of the Families of Great Britain and Ireland, the crest of Sanderson of Lincolnshire is described as: A wolf’s head Sable devouring a man proper, the body, from the small of the back downward, hanging out of his mouth. A truly poignant image along the same theme is Francisco de Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturn_Devouring_His_Son).

Another powerful archetype found in heraldry is the pelican in its piety, that is to say the pelican wounding itself at the breast with its beak to feed its young with its own blood. This image dramatically exemplifies maternal sacrifice and, in a broader context, self-sacrifice for the sake of others (fig. 6). The pelican’s act parallels our own practice of donating blood for transfusions that save lives. Blood shedding is universally considered a symbol of courage and sacrifice. It is ultimately reminiscent of the blood of the lamb, of the crucifixion of Jesus for the sake of humanity. Archetypes always seem to have their opposites, which in this case would be blood taking to kill or for nourishment as in the case of some bats, mosquitoes, leeches, the legendary vampire, and the more modern chupacabra.

Fig. 6 The pelican wounding itself and shedding the blood from its breast to feed its young is a symbol of compassion in the arms granted in 1958 to the Grey Sisters of the Immaculate Conception, whose Mother House is in Pembroke (Ontario).The congregation traditionally administered hospitals. From Beddoe’s Canadian Heraldry (1981): 114.

One can build a coat of arms around an archetype that may constitute completely new heraldic imagery. For instance, spitting in one’s hands to give strength before attempting something especially strenuous is a universal gesture. A farmer may spit in his hands before wielding a heavy axe to split a large block of wood. The idea is that saliva is the essence of life and that it gives strength to one’s hands. Jesus restored sight to a blind man using a poultice of mud made with his spittle (John 9: 6). French speaking Canadian Lumberjacks often accomplished this ritual before lifting a heavy log and sometimes accompanied it with a short incantation which started with “Spiritum Jésome” and then spelt out the number of men involved in lifting. In other words, if there were two men, the incantation would be “Spiritum Jésome deux hommes”. [3] “Spiritum” is the accusative form of “spiritus” meaning breath, breathing, breath of life. Perhaps lumberjacks were not too versed in Latin declensions, but they did go to church where Latin prevailed not so long ago. The word “Jésome” in Canadian French is considered to be an attenuated form of Jesus, but it can also be viewed as a condensed form of “Jésus-homme” or “Jesus-Man”. But however we look at it, the meaning of these words comes across as a form of popular religious incantation asking strength from the Lord to accomplish a strenuous task.

It would be easy to construct a coat of arms around this idea. A single open red hand, red to symbolize strength, with a silver drop in the palm would be a good combination. But if this looked too much like the red hand of Ulster, three hands could be used. The motto could simply be “Spiritum Jésome”. Few people would know precisely what it meant and it might well intrigue the best linguists and scholars, but this motto would convey a religious tone and the meaning would normally be recorded with the symbolism. There is no rule in heraldry excluding a popular phrase of this type, even if it mixes languages and does not correspond to any standard language form.

5. Myths and Legends

Multiple creatures that belong to mythology or fairy tales are present in heraldry. Such creatures or monsters often seem to exemplify a power that man strives for. A number of these, such as Pegasus, dragons, and griffins are winged, and seem specialized in conquering the air, while the mermaid or merman, the sea-lion and sea-horse are masters of the sea. The salamander, the phoenix and the dragon thrive on fire, as does the heraldic panther that has flames shooting out of its mouth and ears. The swift unicorn of fairytales is definitely a land creature, as are the heraldic tiger, the heraldic antelope and the yale, an antelope or goat with the snout and tusks of a boar and two large horns, which it can move alternately forwards and backwards, a feature that would make it a powerful ally on the battlefield!

Heraldry sometimes combines human forms with animal ones as in the case of the mermaid. This practice is found in remotest Antiquity with such monsters as the Minotaur and the gods Thoth, Horus and Anubis. Combining different parts of animals to create monsters such as are found in heraldry is also very ancient. In the Egyptian Book of the Dead, we find judgement scenes where a monster called Amemait, Ammut or Amman sits waiting to devour the hearts of the dead that are so weighed down with sins as to prove heavier than the feather of the goddess of truth Ma’at. Amemait is composed of a crocodile’s head, a lion’s mane, the forepart of a leopard, and the rear part of a hippopotamus (fig. 7). It is certainly complex and intimidating but not very suitable as for the heraldic shield unlike the unicorn which is complex but elegant and associated with more positive concepts. The Canadian Heraldic Authority has created a large number of creatures combining animals together such as in its own arms (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1698&ProjectElementID=5708 and http://news.nationalpost.com/news/canada/how-canada-became-home-to-some-of-the-worlds-more-visually-stunning-and-fun-heraldry. Others include legendary monsters such as the thunderbird (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1303&ProjectElementID=4291) and Ogopogo (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=158&ShowAll=1).

It would be easy to construct a coat of arms around this idea. A single open red hand, red to symbolize strength, with a silver drop in the palm would be a good combination. But if this looked too much like the red hand of Ulster, three hands could be used. The motto could simply be “Spiritum Jésome”. Few people would know precisely what it meant and it might well intrigue the best linguists and scholars, but this motto would convey a religious tone and the meaning would normally be recorded with the symbolism. There is no rule in heraldry excluding a popular phrase of this type, even if it mixes languages and does not correspond to any standard language form.

5. Myths and Legends

Multiple creatures that belong to mythology or fairy tales are present in heraldry. Such creatures or monsters often seem to exemplify a power that man strives for. A number of these, such as Pegasus, dragons, and griffins are winged, and seem specialized in conquering the air, while the mermaid or merman, the sea-lion and sea-horse are masters of the sea. The salamander, the phoenix and the dragon thrive on fire, as does the heraldic panther that has flames shooting out of its mouth and ears. The swift unicorn of fairytales is definitely a land creature, as are the heraldic tiger, the heraldic antelope and the yale, an antelope or goat with the snout and tusks of a boar and two large horns, which it can move alternately forwards and backwards, a feature that would make it a powerful ally on the battlefield!

Heraldry sometimes combines human forms with animal ones as in the case of the mermaid. This practice is found in remotest Antiquity with such monsters as the Minotaur and the gods Thoth, Horus and Anubis. Combining different parts of animals to create monsters such as are found in heraldry is also very ancient. In the Egyptian Book of the Dead, we find judgement scenes where a monster called Amemait, Ammut or Amman sits waiting to devour the hearts of the dead that are so weighed down with sins as to prove heavier than the feather of the goddess of truth Ma’at. Amemait is composed of a crocodile’s head, a lion’s mane, the forepart of a leopard, and the rear part of a hippopotamus (fig. 7). It is certainly complex and intimidating but not very suitable as for the heraldic shield unlike the unicorn which is complex but elegant and associated with more positive concepts. The Canadian Heraldic Authority has created a large number of creatures combining animals together such as in its own arms (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1698&ProjectElementID=5708 and http://news.nationalpost.com/news/canada/how-canada-became-home-to-some-of-the-worlds-more-visually-stunning-and-fun-heraldry. Others include legendary monsters such as the thunderbird (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1303&ProjectElementID=4291) and Ogopogo (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=158&ShowAll=1).

Fig. 7 At the top, the deceased accounts for his life’s deeds before 14 judges. In centre left, the jackal god Anubis leads the deceased to the scales. To the left of the scales’ column, Anubis weighs the heart of the dead against the feather truth and justice. At the right of the scales’ column, Amemait composed of a crocodile’s head, a lion’s mane, the forepart of a leopard, and the rear part of a hippopotamus waits ready to devour any heart weighed-down by sins. On the right of the scales, Thoth, the ibis-headed god of knowledge, records the results of the weighing. In this case, the deceased was judged to be righteous and is led by Horus, the god with the falcon head, to the god Osiris (not seen here), ruler of the underworld. The Egyptian ankh cross, a symbol of life, is held by some of the judges and is found in the left hand of both Anubis and Horus. This cross is present in a number of arms granted by the Canadian Heraldic Authority, for instance: http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=795&ProjectElementID=2857.

Many legends, perhaps based on some actual events, have found their way unto the heraldic shield. One relates to the heart of King Robert the Bruce as reported by the court historian Jean Froissart. The king had brought peace to his kingdom, but although having grown old and feeble still harboured one oppressive regret: that he had not gone to the Holy Land to fight the enemies of the Christian faith. Since his body could no longer fulfill what his heart desired, he asked Sir James Douglas to have his heart embalmed after his death, and to carry it to the Holy Land to be placed on the Holy Sepulchre where the Lord was said to rest.

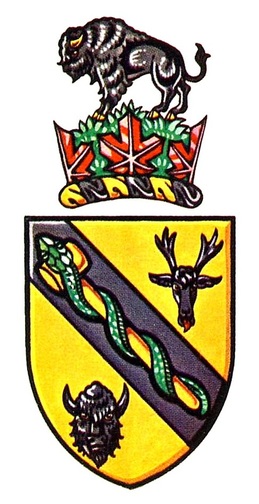

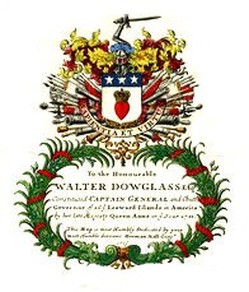

King Robert died in 1329, and Sir James set out on his unusual mission to carry the royal heart to its holy destination. En route he learnt that King Alphonso of Spain was engaged in war against the Saracen and decided on a detour to come to his help. On the field, Douglas rushed rather hastily to the front of the charge, distancing the main body of warriors and causing his troops to be surrounded by the enemy. Seeing this predicament, Douglas cast the royal heart before him towards the enemy in an attempt to fulfill the king’s desire to lead a charge on a crusade battleground. The legend goes on to say that one of the Christian knights later found the heart and brought it back to Scotland to be buried at Melrose Abbey. This would explain the crowned red heart added to the arms of the Douglas family in recognition of Sir James’ unusual feat (fig. 8).

King Robert died in 1329, and Sir James set out on his unusual mission to carry the royal heart to its holy destination. En route he learnt that King Alphonso of Spain was engaged in war against the Saracen and decided on a detour to come to his help. On the field, Douglas rushed rather hastily to the front of the charge, distancing the main body of warriors and causing his troops to be surrounded by the enemy. Seeing this predicament, Douglas cast the royal heart before him towards the enemy in an attempt to fulfill the king’s desire to lead a charge on a crusade battleground. The legend goes on to say that one of the Christian knights later found the heart and brought it back to Scotland to be buried at Melrose Abbey. This would explain the crowned red heart added to the arms of the Douglas family in recognition of Sir James’ unusual feat (fig. 8).

Fig. 8 The traditional crown and red heart of Douglas appear in the coat of arms accompanying the dedication of a map to Walter Douglas, Governor of the Leeward Islands from 1710-16. The map is of North America by Herman Moll and dated 1715. Examples of this map are in the collection of Library and Archives Canada, NMC 21061: http://data2.collectionscanada.gc.ca/nmc/n0021061k.pdf

Many of the legends that found their way unto the heraldic shield are rather bloody because they belong to the battlefield, the ground on which honour was achieved. The simple arms of Austria, a white horizontal band on a red field, are said to originate from such a gory event. As the story goes, the Margrave Leopold II of Austria returned from an especially fierce battle his coat reddened with blood. When he removed his belt, a white band that had been protected from drenching appeared underneath. Seeing in this a divine sign, he adopted the white band on red as a national emblem.

Religious legends or beliefs are also frequent in emblems. The shield of the picturesque French city of Aigues-Mortes shows St. Martin on horseback cutting half of his cloak with a sword and offering it to a scantily clad beggar with a crutch. The same imagery is found in the municipal arms of Limoux (France), of the Borough of Dover (England), and of Bingen am Rhein (Germany). In 1945 the Canadian city of Westmount was granted arms that displayed a smaller shield with a black raven carrying a piece of bread in its beak. The raven referred to St. Anthony who, according to legend, was fed by ravens bombarding his hermit’s refuge in the Egyptian desert with morsels of bread. The allusion to St. Anthony is explained by the fact that the former name of the municipality was “Côte Saint-Antoine” (fig. 9). The arms of Oslo display St. Hallvard holding arrows and a millstone with a naked maiden at his feet. This imagery relates to the saint’s attempt to rescue a maiden from pursuers who shot him with arrows and threw his body into the water weighed down by a millstone.

Religious legends or beliefs are also frequent in emblems. The shield of the picturesque French city of Aigues-Mortes shows St. Martin on horseback cutting half of his cloak with a sword and offering it to a scantily clad beggar with a crutch. The same imagery is found in the municipal arms of Limoux (France), of the Borough of Dover (England), and of Bingen am Rhein (Germany). In 1945 the Canadian city of Westmount was granted arms that displayed a smaller shield with a black raven carrying a piece of bread in its beak. The raven referred to St. Anthony who, according to legend, was fed by ravens bombarding his hermit’s refuge in the Egyptian desert with morsels of bread. The allusion to St. Anthony is explained by the fact that the former name of the municipality was “Côte Saint-Antoine” (fig. 9). The arms of Oslo display St. Hallvard holding arrows and a millstone with a naked maiden at his feet. This imagery relates to the saint’s attempt to rescue a maiden from pursuers who shot him with arrows and threw his body into the water weighed down by a millstone.

Fig. 9 The arms granted to Westmount (Quebec) in 1945 display a smaller shield with a raven carrying a morsel of bread in its beak. It refers to the raven that fed Saint Anthony in the Egyptian desert and to Côte Saint-Antoine, the former name of Westmount. From Heraldry in Canada / L’Héraldique au Canada 1, no. 4 (July, August, September 1967): 1.

The arms of the Brandenburg von Wedells tell a sad story, but with a romantic twist. During a hunt the daughter of the king of Brandenburg got caught in a millwheel. The miller, seeing her predicament, managed to stop the wheel in the nick of time with his bare hands, but also lost both his arms in the process. As good fortune would have it, the king was so overwhelmed with gratitude that he gave the miller his daughter’s hand and made him a noble with his own coat of arms, namely a millwheel on the shield and an armless man as crest. Some have punned with a degree of black humour that he had both lost and gained arms. [4]

Clairvoyance or the ability to see into the future is seen as an attribute of prophets and shamans and of such seers as Joseph in the Old Testament. The seeds of what the future holds are likely to be already found in mythology, legends, biblical accounts, fairy tales, and the works of imaginative authors. Early man expressed in myths and legends some of the powers that belong to animals: birds that fly, fish that are at home in the sea, and land animals like horses that can swiftly cover long distances. All these desires were fulfilled through man’s ingenuity in creating fantastic machines. Quite a number of these machines such as planes, trains, and boats have found their way unto the heraldic shield, though in such cases it is best only to use a significant part of a large machine, such as a propeller, a boat wheel, or a locomotive wheel.

Instant displacement is not an idea exclusive to Star Trek, since the same notion is found in the apparitions of angels, saints, and fairies. Communication without language, also termed mind reading, telepathy or ESP is as old as recorded history and has received considerable scientific attention for about a century. The search for immortality is as old as man and is dramatized by Juan Ponce de León’s search for the fountain of youth. When such abilities cease to be in the realm of legends, myths or the supernatural and become reality, perhaps through a better understanding of brain functions or some wonderful machine or drug, they could be given heraldic expression by drawing on both ancient and modern imagery. A modern example of this idea is the alternating bird wings and stars on an astral coronet to represent the Air Force and flight which is beginning to make travel to the stars a reality. Billets (rectangles) have been used in modern heraldry to represent computer chips (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1338&ShowAll=1). Depictions of atoms or neutrons also appear in some grant of arms (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1180&ShowAll=1).

6. Heraldry Creates Its Own Fables

In July 1985, two peace campers on Parliament Hill, protesting the testing of U.S. missiles in Canada, attacked two sculptures in front of the Peace Tower with a hammer. This was an unfortunate act of vandalism against two beautiful works of art, the lion holding the royal shield and the unicorn that of Canada, both sculptured by Coeur-de-Lion MacCarthy and Cléophas Soucy and now part of the national heritage. It seems that the chain of the unicorn in particular had been the victim of a great deal of this destructive rage. I was asked to speak on the radio concerning the significance of the unicorn’s chain, which is often viewed as the enslavement of French Canada. Ten years later, on 1 December 1995, a letter in the newspaper Le Devoir resurrected the same idea that the unicorn in Canada’s arms represented Quebec and the chain “servitude”. I refuted this on December 17, but the myth lives on. I encountered it recently on the internet.

It is understandable that francophone Canadians should view the unicorn as representing them, since it holds the old banner of France that flew from Pierre Du Gua de Monts’ lodgings at his settlement on Île Sainte-Croix (Dochet Island) in 1604. The chain is further suspended from a coronet topped with fleurs-de-lis around the unicorn’s neck. But history tells quite another story since the origin of the chained unicorn now in Canada’s arms predates the discovery of Canada by more than a century.

During the reign of James I (1424-1437), the chained unicorn replaced the dragon as a supporter of the arms of Scotland. James III (1460-1488), it seems, used a single unicorn supporter, and by 1503 James IV had adopted two unicorns. In 1603, when James VI of Scotland also became James I of England, he introduced the unicorn into the arms of England as one of its supporters, and eventually the unicorn became a supporter for most members of the Royal Family. From these noble sources, the unicorn made its way to Canada, first as the left supporter of the arms of Nova-Scotia, c. 1625, then in 1637, within the second and third quarters of the arms of Newfoundland. In 1921 the unicorn became the right supporter of Canada`s arms, and in 1992, the governor general, as head of the Canadian Heraldic Authority, granted a unicorn as dexter supporter in augmentation to the arms of Manitoba, recognizing the importance of Scottish settlement in that province.

However, why the unicorn is chained in the first place is more difficult to explain. Chaining animals in heraldry is a common practice and many of the chained animals such as bulls, deer, lions, griffins, and unicorns are strong, swift or ferocious. One can hardly speak of enslavement since the chain's end is generally not tied down. If fetters were originally intended, the animal obviously got away bringing along both collar and chain. In heraldry, chained animals retain a haughty independent appearance, almost as if they had voluntarily chosen to serve the armiger (bearer of arms). Their chain seems to convey a notion of discipline, but without diminishment. One is reminded of the motto "Libre et ordonné", chosen by the late Right Honourable Roland Michener, former Governor General of Canada.

Chevalier and Gheerbrant’s dictionary of symbolism states that the chain does not necessarily signify enslavement: “In the sociopsychological context, chains symbolize the need to adapt to communal life and the ability to integrate with the group”. One Scottish armorist, recalling that the unicorn would rather die than be brought to submission, thought that the creature was intended to declare Scotland's sovereign independence, but he offered no explanation of its collar and chain. One interpretation is that the beast having been tamed and its haughty spirit daunted, was enlisted to serve the Scottish King. A corollary of this is that the chained unicorn in the royal arms of Scotland, England, and Canada is a beast with special qualities made to serve the sovereign.

Some have viewed the combination of the fleurs-de-lis banner and unicorn as symbolic of the old alliance between Scotland and France. But the more likely reason why the unicorn is holding the banner of France in Canada’s arms is that it had little choice in the matter. The committee that designed the arms of Canada wanted to represent the founding nations. Since it was normal for the lion, an emblem of England, to hold the Union Flag, the unicorn was left with the banner of royal France. The original idea of including banners had come from the royal arms of France in which two angels hold the old banner of France. But lifting an angel from the arms of royal France was put down by Edward Marion Chadwick, a heraldist from Toronto, who strongly objected to the coupling of an angel with a beast. In any case those who designed the Canadian arms would not have honoured the French as a founding nation by placing fleurs-de-lis on the shield and then surreptitiously introducing the base idea of their enslavement in the chain (See on this site the article The Unicorn in Canada [http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/the-unicorn-in-canada.html] and chapter 4 the work Canada’s Coat of Arms [http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/chapter-4-one-resolute-man.html]). Though I have responded to inquiries, spoken on the radio and written articles on the matter, the idea of the chain signifying enslavement keeps coming back and will keep on resurging. It has become part of popular folklore or myth.

The three maple leaves on one stem in base of the shield of Canada’s arms have also given rise to considerable speculation. These three leaves first appeared as Canadian symbols in the shields granted to Ontario and Quebec in 1868. In successive booklets printed on the arms of Canada by the government from 1921, it is merely stated that the sprig of three maple leaves is there as an emblem of Canada. But the public incubated other interpretations, namely, that the leaves represent the Trinity, Eastern, Central and Western Canada or Francophones, Anglophones and Indigenous Peoples.

Another irrepressible notion relates to the symbolism of the Canadian flag in which some want to see Canada’s geography. A flag much flaunted during the Flag Debate was the so-called Pearson Pennant composed of three red maple leaves on one stem over a white field and two blue vertical bands on both sides meant to represent Canada “from sea to sea” (fig. 10). In the present flag, although the bands are red, the idea of seas has survived in the minds of many.

Clairvoyance or the ability to see into the future is seen as an attribute of prophets and shamans and of such seers as Joseph in the Old Testament. The seeds of what the future holds are likely to be already found in mythology, legends, biblical accounts, fairy tales, and the works of imaginative authors. Early man expressed in myths and legends some of the powers that belong to animals: birds that fly, fish that are at home in the sea, and land animals like horses that can swiftly cover long distances. All these desires were fulfilled through man’s ingenuity in creating fantastic machines. Quite a number of these machines such as planes, trains, and boats have found their way unto the heraldic shield, though in such cases it is best only to use a significant part of a large machine, such as a propeller, a boat wheel, or a locomotive wheel.

Instant displacement is not an idea exclusive to Star Trek, since the same notion is found in the apparitions of angels, saints, and fairies. Communication without language, also termed mind reading, telepathy or ESP is as old as recorded history and has received considerable scientific attention for about a century. The search for immortality is as old as man and is dramatized by Juan Ponce de León’s search for the fountain of youth. When such abilities cease to be in the realm of legends, myths or the supernatural and become reality, perhaps through a better understanding of brain functions or some wonderful machine or drug, they could be given heraldic expression by drawing on both ancient and modern imagery. A modern example of this idea is the alternating bird wings and stars on an astral coronet to represent the Air Force and flight which is beginning to make travel to the stars a reality. Billets (rectangles) have been used in modern heraldry to represent computer chips (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1338&ShowAll=1). Depictions of atoms or neutrons also appear in some grant of arms (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1180&ShowAll=1).

6. Heraldry Creates Its Own Fables

In July 1985, two peace campers on Parliament Hill, protesting the testing of U.S. missiles in Canada, attacked two sculptures in front of the Peace Tower with a hammer. This was an unfortunate act of vandalism against two beautiful works of art, the lion holding the royal shield and the unicorn that of Canada, both sculptured by Coeur-de-Lion MacCarthy and Cléophas Soucy and now part of the national heritage. It seems that the chain of the unicorn in particular had been the victim of a great deal of this destructive rage. I was asked to speak on the radio concerning the significance of the unicorn’s chain, which is often viewed as the enslavement of French Canada. Ten years later, on 1 December 1995, a letter in the newspaper Le Devoir resurrected the same idea that the unicorn in Canada’s arms represented Quebec and the chain “servitude”. I refuted this on December 17, but the myth lives on. I encountered it recently on the internet.

It is understandable that francophone Canadians should view the unicorn as representing them, since it holds the old banner of France that flew from Pierre Du Gua de Monts’ lodgings at his settlement on Île Sainte-Croix (Dochet Island) in 1604. The chain is further suspended from a coronet topped with fleurs-de-lis around the unicorn’s neck. But history tells quite another story since the origin of the chained unicorn now in Canada’s arms predates the discovery of Canada by more than a century.