Adding and Subtracting Lions

Auguste Vachon, Outaouais Herald Emeritus

The origin of the arms of England with three gold lions on a red field, walking by and looking at the spectator (passant guardant), has been the object of considerable speculation. A persistent theory, espoused at times by both French and English authors, is that, after Henry II married Eleanor Duchess of Aquitaine in 1152, he added the lion of the Dukedom of Aquitaine (also called Guyenne) to the two lions of the Dukedom of Normandy (another of his possessions). The addition was believed to have created the three-lion emblem of England. Although this hypothesis seems eminently logical, it has been disputed by several historians. While it is certain that the old French provinces (before Napoleon) of Normandy and Guyenne were identified armorially by two and one lion respectively, establishing precisely how and when each province acquired these felines is another matter. Lions in trios, duos or singly later crossed the Atlantic to be featured in Canadian heraldry, both personal and public, to signify Anglo-Saxon origins or a link with the British Crown.

England’s Three Lions

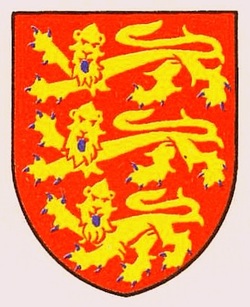

The only reliable information we have regarding the origin of the three lions of England is the second equestrian seal of Richard I dated 1198. On it Richard Cœur de Lion or the Lionheart is seen bearing a shield with three of these beasts positioned on all fours (fig. 1). The three lions remained the arms of England until 1340 when Edward III quartered them with the fleurs-de-lis of France to signify his pretention to the French Crown. We also know that, on his first seal of 1189, the Lionheart holds a shield displaying on one side a single lion rampant (standing) and looking to the right. This has given rise to speculation that there was another lion on the other side of the shield facing left, in other words two lions standing and facing each other, combatant in heraldic terminology. We also know that the Lionheart’s brother, John Lackland, before becoming king, used a seal with two lions passant guardant. It is also suggested by literary sources that Henry II, the father of Richard and John, may have borne a red shield with a gold lion rampant. Possibly as well, the three lions of Richard were inspired by the two lions of John, in the sense that Richard may have wanted to get one up on his younger brother. The lions attributed to English Kings from William the Conqueror to Richard I are likely anachronisms.[1]

The only reliable information we have regarding the origin of the three lions of England is the second equestrian seal of Richard I dated 1198. On it Richard Cœur de Lion or the Lionheart is seen bearing a shield with three of these beasts positioned on all fours (fig. 1). The three lions remained the arms of England until 1340 when Edward III quartered them with the fleurs-de-lis of France to signify his pretention to the French Crown. We also know that, on his first seal of 1189, the Lionheart holds a shield displaying on one side a single lion rampant (standing) and looking to the right. This has given rise to speculation that there was another lion on the other side of the shield facing left, in other words two lions standing and facing each other, combatant in heraldic terminology. We also know that the Lionheart’s brother, John Lackland, before becoming king, used a seal with two lions passant guardant. It is also suggested by literary sources that Henry II, the father of Richard and John, may have borne a red shield with a gold lion rampant. Possibly as well, the three lions of Richard were inspired by the two lions of John, in the sense that Richard may have wanted to get one up on his younger brother. The lions attributed to English Kings from William the Conqueror to Richard I are likely anachronisms.[1]

Fig. 1. The three lions borne by English Kings from 1198 to 1340 and as the main quarter of the royal arms to this day.

In 1884 the famous genealogist and Ulster King of Arms, Sir Bernard Burke, attributed Gules two lions passant guardant Or to William I the Conqueror. He ascribed the same arms to Henry II Plantagenet, but notes that the two lions were previous “to the King’s marriage with Eleanor of Aquitaine, when he adopted a third lion for Aquitaine.”[2] Referring to the shield of Bordeaux, Jiří Louda states “The basic charge in the city arms is the lion of Eleanor (the arms of the Duchy of Guyenne).” In a footnote the editor, Dermot Morrah, Arundel Herald Extraordinary, cautions “ Whether this lion is the origin of the three lions (or leopards) of England, which appear for the first time in the second Great Seal of Eleanor’s son, King Richard I, is a matter for speculation.”[3] A more recent work states: “The coat of Gules two Lions passant guardant Gold is generally attributed to the Norman kings … and it was the first Angevin Henry II (1154-89), who added a third lion, perhaps that of his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine who is known to have borne a single gold lion or red.”[4] Another recent work on the royal families of Europe does not hesitate to attribute two gold lions on red to William the Conqueror and one lion on red to Eleanor of Aquitaine.[5]

Other authors dispute the theory of one lion added to two to create the three-lion shield of England “The third lion does not appear in the arms of the English kings until the end of Richard I’s reign, and the theory that Henry II derived it from the arms of Aquitaine in right of his wife has nothing to support it.”[6] Early editions of Burke’s Peerage attributed two lions to William I up to Henry II who later adopted three lions.[7] But more recent editions of Burke’s only illustrate the three lions beginning with Richard I and make no changes to the royal arms until Edward III when the lilies of France are introduced.[8] Meaudre de Lapouyade rejects the idea that Henry II bore two lions and added another after his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine. In fact he very much doubts that Henry even used a heraldic shield.[9] Based on the learned works of Max Prinet and Lapouyade, Jacques Meurgey de Tupigny also dismisses as unfounded the theory of the addition of lions to create the arms of England.[10] The tombs of Alfonso VIII of Castile and that of his wife Eleanor of England (c. 1161-1214), daughter of Henry II of England and sister of Richard the Lionheart, are side by side in the Monastery of Santa María Real de las Huelgas in Burgos, Spain. The Plantagenet arms on Eleanor’s tomb display three lions.

Other authors dispute the theory of one lion added to two to create the three-lion shield of England “The third lion does not appear in the arms of the English kings until the end of Richard I’s reign, and the theory that Henry II derived it from the arms of Aquitaine in right of his wife has nothing to support it.”[6] Early editions of Burke’s Peerage attributed two lions to William I up to Henry II who later adopted three lions.[7] But more recent editions of Burke’s only illustrate the three lions beginning with Richard I and make no changes to the royal arms until Edward III when the lilies of France are introduced.[8] Meaudre de Lapouyade rejects the idea that Henry II bore two lions and added another after his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine. In fact he very much doubts that Henry even used a heraldic shield.[9] Based on the learned works of Max Prinet and Lapouyade, Jacques Meurgey de Tupigny also dismisses as unfounded the theory of the addition of lions to create the arms of England.[10] The tombs of Alfonso VIII of Castile and that of his wife Eleanor of England (c. 1161-1214), daughter of Henry II of England and sister of Richard the Lionheart, are side by side in the Monastery of Santa María Real de las Huelgas in Burgos, Spain. The Plantagenet arms on Eleanor’s tomb display three lions.

Normandy’s Two Lions

The first example I have found of the two lions of England being associated with Normandy is on a seal of John Lackland as Count of Mortain attached to a document concerning the donation of the revenues of the Chapel of Blye in England to the Archbishop of Rouen. The document is not dated but is deemed to be c. 1189 when Lackland was created Count of Mortain, a region in Normandy. The seal, however, only mentions his title as son of the English King and Lord of Ireland (Sigillum Johannis, filii regis Anglie, domini Hibernie). This means that the seal is the one John used in general and is not specific to Normandy. The imagery on the seal is described as an equestrian figure holding a shield with two lions (?) passant.[11] The question mark which follows the lions is likely due to a fuzzy or damaged impression, but we know from other sources that John Lackland’s seal did feature two lions passant guardant.

John replaced his two lions by three when he acceded to the English throne in 1199. There is no evidence that his two lions were ever used as the emblem of Normandy, which he lost to France in 1204. Henry V reconquered Normandy from 1417 to 1419, but the French recovered it towards the end of the war and achieved permanent control in 1450.

It was likely during the fifteen century that the two gold lions on red appeared on the shield of Normandy. The Armorial Bellenville, which dates from the last quarter of the fourteenth century, gives to Normandy: Azure semy of fleurs-de- lis Or within a bordure Argent. An annotation in the published version informs us that these arms were borne by the French King Charles V as Duke of Normandy before his death in1364.[12] A fifteenth century armorial in the Bibliothèque nationale de France displays the two gold lions on red for the Dukes of Nomandy (see: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b530239616/f36.image).[13] The same arms are also found in the fifteenth century section of the armorial Le Breton.[14] A seal featuring two lions on a semy of fleurs-de-lis was recently brought to light at the Departmental Archives of Calvados. It is from the time of Henry VI of England who was also Duke of Normandy from 1422 to 1450. More specifically, the seal dates from the 1440’s and is deemed to be the oldest evidence of its type, pointing again to a fifteen century origin for the two lions of Normandy (see: http://france3-regions.francetvinfo.fr/basse-normandie/les-archives-du-calvados-devoile-le-plus-ancien-sceau-aux-deux-leopards-980754.html). The late appearance of the two lions of Normandy in armorials reinforces the probability that the Norman shield came into existence in the fifteenth century some years after the English reconquered Normandy from 1417 to 1419. By the same token, it excludes the possibility that the three lions of England were constituted by the two lions of Normandy added to the single lion of Aquitaine at the time of Henry II.

The first example I have found of the two lions of England being associated with Normandy is on a seal of John Lackland as Count of Mortain attached to a document concerning the donation of the revenues of the Chapel of Blye in England to the Archbishop of Rouen. The document is not dated but is deemed to be c. 1189 when Lackland was created Count of Mortain, a region in Normandy. The seal, however, only mentions his title as son of the English King and Lord of Ireland (Sigillum Johannis, filii regis Anglie, domini Hibernie). This means that the seal is the one John used in general and is not specific to Normandy. The imagery on the seal is described as an equestrian figure holding a shield with two lions (?) passant.[11] The question mark which follows the lions is likely due to a fuzzy or damaged impression, but we know from other sources that John Lackland’s seal did feature two lions passant guardant.

John replaced his two lions by three when he acceded to the English throne in 1199. There is no evidence that his two lions were ever used as the emblem of Normandy, which he lost to France in 1204. Henry V reconquered Normandy from 1417 to 1419, but the French recovered it towards the end of the war and achieved permanent control in 1450.

It was likely during the fifteen century that the two gold lions on red appeared on the shield of Normandy. The Armorial Bellenville, which dates from the last quarter of the fourteenth century, gives to Normandy: Azure semy of fleurs-de- lis Or within a bordure Argent. An annotation in the published version informs us that these arms were borne by the French King Charles V as Duke of Normandy before his death in1364.[12] A fifteenth century armorial in the Bibliothèque nationale de France displays the two gold lions on red for the Dukes of Nomandy (see: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b530239616/f36.image).[13] The same arms are also found in the fifteenth century section of the armorial Le Breton.[14] A seal featuring two lions on a semy of fleurs-de-lis was recently brought to light at the Departmental Archives of Calvados. It is from the time of Henry VI of England who was also Duke of Normandy from 1422 to 1450. More specifically, the seal dates from the 1440’s and is deemed to be the oldest evidence of its type, pointing again to a fifteen century origin for the two lions of Normandy (see: http://france3-regions.francetvinfo.fr/basse-normandie/les-archives-du-calvados-devoile-le-plus-ancien-sceau-aux-deux-leopards-980754.html). The late appearance of the two lions of Normandy in armorials reinforces the probability that the Norman shield came into existence in the fifteenth century some years after the English reconquered Normandy from 1417 to 1419. By the same token, it excludes the possibility that the three lions of England were constituted by the two lions of Normandy added to the single lion of Aquitaine at the time of Henry II.

Fig. 2. Arms of the Province of Normandy. The two gold lions of Normandy appeared with fleurs-de-lis on a seal of Henry VI in the 1440’s. The two lions also grace the red shield of the Dukes of Normandy in the fifteenth century.

Guyenne’s Single Lion

In 1152 Eleanor of Aquitaine married Henry, Duke of Normandy and Count of Anjou, who became King Henry II of England in 1154 and ruled over Guyenne (or Aquitaine) in right of his wife. As a result of a treaty between Louis IX of France and Henry III of England in 1259, English kings held the Duchy of Guyenne as feudatories of the Kings of France. In 1294 war over Guyenne broke out between Philip IV of France and Edward I of England. Though French armies eventually gained the upper hand, Guyenne was returned to England by the Treaty of Paris in 1303 after complex negotiations involving nuptial alliances between the two rival dynasties. As a result, Bordeaux was under French control for a short period from 1294 to 1303. In 1338 Philip VI of France initiated a serious campaign to retake Guyenne, but he was unable to capture Bordeaux and abandoned his efforts in 1340 to concentrate on other fronts. By the Treaty of Brétigny in 1360, the French ceded extensive territories in northwestern France to England and Edward III renounced his claim to the throne of France. But the treaty was soon breached with fighting resuming in 1369. With the Battle of Castillon in 1453, France gained permanent control of the territory.

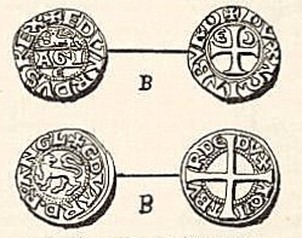

By comparing a 1297 seal of Bordeaux featuring a fleur-de-lis (fig. 3) with a fragment of a 1342 seal of that city displaying a lion (fig. 4), Meaudre de Lapouyade is able to demonstrate that the lion replaced the fleur-de-lis as the ducal emblem of Guyenne under English rule. Lapouyade also gives examples of the change from fleurs-de-lis to lions on the seals of the Palais de l’Ombrière which was the usual residence of the Dukes of Guyenne inside the City of Bordeaux.[15] Other examples of the single lion as the mark of the Dukes of Guyenne are found on deniers (fig. 5) at the time of Edward I (1272-1306) and on coins of various denominations (fig. 6) during the reign of Edward II (1307-1327).

In 1152 Eleanor of Aquitaine married Henry, Duke of Normandy and Count of Anjou, who became King Henry II of England in 1154 and ruled over Guyenne (or Aquitaine) in right of his wife. As a result of a treaty between Louis IX of France and Henry III of England in 1259, English kings held the Duchy of Guyenne as feudatories of the Kings of France. In 1294 war over Guyenne broke out between Philip IV of France and Edward I of England. Though French armies eventually gained the upper hand, Guyenne was returned to England by the Treaty of Paris in 1303 after complex negotiations involving nuptial alliances between the two rival dynasties. As a result, Bordeaux was under French control for a short period from 1294 to 1303. In 1338 Philip VI of France initiated a serious campaign to retake Guyenne, but he was unable to capture Bordeaux and abandoned his efforts in 1340 to concentrate on other fronts. By the Treaty of Brétigny in 1360, the French ceded extensive territories in northwestern France to England and Edward III renounced his claim to the throne of France. But the treaty was soon breached with fighting resuming in 1369. With the Battle of Castillon in 1453, France gained permanent control of the territory.

By comparing a 1297 seal of Bordeaux featuring a fleur-de-lis (fig. 3) with a fragment of a 1342 seal of that city displaying a lion (fig. 4), Meaudre de Lapouyade is able to demonstrate that the lion replaced the fleur-de-lis as the ducal emblem of Guyenne under English rule. Lapouyade also gives examples of the change from fleurs-de-lis to lions on the seals of the Palais de l’Ombrière which was the usual residence of the Dukes of Guyenne inside the City of Bordeaux.[15] Other examples of the single lion as the mark of the Dukes of Guyenne are found on deniers (fig. 5) at the time of Edward I (1272-1306) and on coins of various denominations (fig. 6) during the reign of Edward II (1307-1327).

Fig. 3. This 1297 seal of Bordeaux (reverse) clearly shows a fleur-de-lis between the heads of two men standing inside turrets and sounding the trumpet. From M. Lapouyade, Armoiries de Bordeaux (1913), plate I, no. II, after p. 6.

Fig. 4. Fragment from a 1342 seal (reverse) which shows a lion between the heads of the trumpeters. From M. Lapouyade, Armoiries de Bordeaux (1913), plate I, no. IV, after p. 6.

Fig. 5. Deniers (coins) for the region of Bordeaux at the time of Edward I (1272-1306), displaying on the obverse the single lion of the king as Duke of Guyenne. From M. Lapouyade, Armoiries de Bordeaux (1913), p. 8.

Fig. 6. One pound coin for the region of Bordeaux displaying the single lion of Edward II (1307-1327) as Duke of Guyenne, dated 1316. From M. Lapouyade, Armoiries de Bordeaux (1913), plate II, no. II, after p. 10. Other denominations (plate II, nos. IV, V) with the same single lion are dated 1315 and 1316.

Lapouyade searched in vain for a lion passant guardant that could be associated with Eleanor of Aquitaine or that was issued from the soil of Aquitaine. He has found no documentation to support such a claim.[16] Regarding the single lion of Guyenne, Meurgey de Tupigny merely states: “These arms are sometimes attributed to the Kingdom of Aquitaine which preceded that of Guyenne.”[17] He neither denies nor supports this notion.

When did the shield of arms of the Province of Guyenne come into being? Meurgey de Tupigny’s work on the arms of the old provinces of France provides no date.[18] The Armorial Bellenville, which as we have seen dates from the last quarter of the fourteenth century, ascribes to Gascogne Gules a lion passant guardant Or. The authors of the commentaries accompanying the published armorial identify Gascogne with Aquitaine or Guyenne.[19] The same arms are found in the fifteenth century section of the armorial Le Breton.[20] The fifteenth century armorial quoted above for Normandy also contains the single lion arms of the Duke of Guyenne, see http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b530239616/f36.image.

When did the shield of arms of the Province of Guyenne come into being? Meurgey de Tupigny’s work on the arms of the old provinces of France provides no date.[18] The Armorial Bellenville, which as we have seen dates from the last quarter of the fourteenth century, ascribes to Gascogne Gules a lion passant guardant Or. The authors of the commentaries accompanying the published armorial identify Gascogne with Aquitaine or Guyenne.[19] The same arms are found in the fifteenth century section of the armorial Le Breton.[20] The fifteenth century armorial quoted above for Normandy also contains the single lion arms of the Duke of Guyenne, see http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b530239616/f36.image.

Fig. 7. The single gold lion on red of Guyenne appeared on coins early in the fourteenth century and on the shield of the Dukes of Guyenne at the end of the same century and possibly before.

Lions one, two, three in Canada

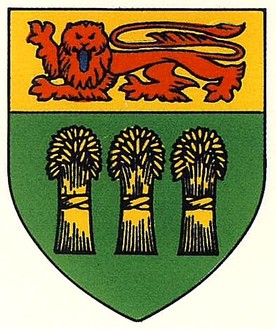

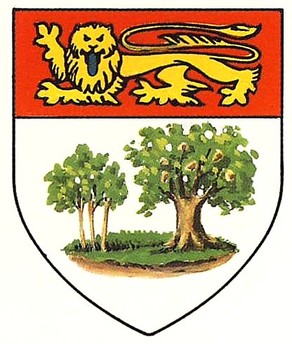

The single lion of England is present in a number of Canadian personal arms to designate British origin or a link with the Crown. In those of Alan Beddoe, Founding President of the Heraldry Society of Canada, a gold lion holds a shield with a single red maple leaf to emphasize that the granting of arms in Canada is a royal prerogative. The single lion also appears in a number of public arms. It is featured, repeated twice, in the arms granted to Newfoundland when it was a crown colony. It also figures prominently in the provincial arms of Quebec, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Saskatchewan. It is found in the crest (above the helmet) in the achievement of arms of British Columbia as well as in the crest of Canada’s national arms, which crest is also the identifying mark of the office of governor general of Canada (figs. 8-14). The lion is derived from the arms of England which has three of them, but one lion was deemed adequate to represent the relationship of a Canadian colony or province with the British Crown as was the case for Guyenne in former times.

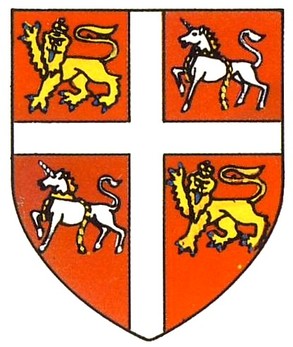

The escutcheon of Normandy with its two lions is included in the shield granted to the Association des Fortin d'Amérique by the Chief Herald of Canada on 15 November 2004, http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=408&ShowAll=1. The three lions of England are found in the first quarter of the armorial bearings of Canada (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=461&ProjectElementID=1555) as well as in the arms of Fredericton which, after considerable discussion, were granted by the Kings of Arms of England in 1971 and registered by the Chief Herald of Canada in 1992, http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1592&ProjectElementID=5331.

The single lion of England is present in a number of Canadian personal arms to designate British origin or a link with the Crown. In those of Alan Beddoe, Founding President of the Heraldry Society of Canada, a gold lion holds a shield with a single red maple leaf to emphasize that the granting of arms in Canada is a royal prerogative. The single lion also appears in a number of public arms. It is featured, repeated twice, in the arms granted to Newfoundland when it was a crown colony. It also figures prominently in the provincial arms of Quebec, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Saskatchewan. It is found in the crest (above the helmet) in the achievement of arms of British Columbia as well as in the crest of Canada’s national arms, which crest is also the identifying mark of the office of governor general of Canada (figs. 8-14). The lion is derived from the arms of England which has three of them, but one lion was deemed adequate to represent the relationship of a Canadian colony or province with the British Crown as was the case for Guyenne in former times.

The escutcheon of Normandy with its two lions is included in the shield granted to the Association des Fortin d'Amérique by the Chief Herald of Canada on 15 November 2004, http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=408&ShowAll=1. The three lions of England are found in the first quarter of the armorial bearings of Canada (http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=461&ProjectElementID=1555) as well as in the arms of Fredericton which, after considerable discussion, were granted by the Kings of Arms of England in 1971 and registered by the Chief Herald of Canada in 1992, http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1592&ProjectElementID=5331.

|

Fig. 8. Newfoundland, King Charles I, 1637.

Fig. 10. New Brunswick, Queen Victoria, 1868.

Fig. 12. Saskatchewan, King Edward VII, 1906.

|

Fig. 9. Quebec, Queen Victoria, 1868. Originally granted with two blue fleurs-de-lis on gold; changed to three gold fleurs-de-lis on blue by the province in 1939.

Fig. 11. Prince Edward Island, King Edward VII, 1905.

Fig. 13. This device, which replicates the crest of the achievement of arms of the United Kingdom, was adopted by British Columbia in 1870. With adaptations, it was granted as the crest of the province’s achievement of arms in 1987. See the full story on this site: http://heraldicscienceheraldique.com/arms-and-devices-of-provinces-and-territories.html.

|

Fig. 14. The crest of the achievement of arms of Canada is used as the unique figure on the blue flag of the Governor General of Canada and as a symbol of the viceregal office, approved by Queen Elizabeth II in 1981. See the full achievement of arms of Canada at: http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=461&ProjectElementID=1555.

Conclusion

We know that, beginning with the second equestrian seal of Richard I dated 1198, the Kings of England bore a shield with three gold lions on red. It was long believed that these lions were an addition of the two lions of Normandy with the one lion of Guyenne after the marriage of Henry II and Eleanor Duchess of Aquitaine in 1152, but there seems to be no concrete evidence to support this theory. On the other hand, there exists solid evidence that the Dukes of Normandy adopted two lions from the 1440’s. We also know that the single lion of the Kings of England as Dukes of Guyenne appeared on the seals and coins of Bordeaux in the early fourteenth century and possibly in the last quarter of the thirteenth century. Again there seems to be no evidence that such a lion was the emblem of Eleanor as Duchess of Aquitaine. In other words, the three lions of England were not the result of an addition of the two lions of Normandy with the single lion of Guyenne. In fact the documentation available demonstrates that the two lions of Normandy and the one lion of Guyenne were subtractions from the three lion of England to show the relationship between vassal and suzerain. This same type of subtraction was done to show the link between England and some Canadian colonies and provinces (figs. 8-14). It is somewhat like military ranks being designated by three, two, and one star depending on the rank.

Further reading – This article closely relates to the achievement of arms of Bordeaux whose single lion was long believed to be derived from the one attributed to Eleanor of Aquitaine. The history of the arms of Bordeaux does shed considerable light on the single lion of Aquitaine or Guyenne. As I progressed with this article, it became evident that the long and complex story of Bordeaux’s arms warranted an article of its own, see: The Achievement of Arms of Bordeaux: an Emblem Born in Strife.

Websites

All the websites cited in this article were consulted on 15 June 2016.

Notes

[1] Richard Marks and Ann Payne, British Heraldry from its Origins to c. 1800 (London: British Museum Publications, 1978), pp. 103, 109; Rodney Dennys, The Heraldic Imagination (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1976), pp. 30-31.

[2] Sir Bernard Burke, The General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales (London: Harrison, 1884), pp. lv-lvi.

[3] Jiří Louda, European Civic Coats of Arms (London: Paul Hamlyn, 1966), pp. 106-07.

[4] Stephen Friar, Heraldry (Stroud [Gloucestershire]: Sutton Publishing, 1996), pp. 232-33.

[5] Jiří Louda and Michael Maclagan, Heraldry of the Royal Families of Europe (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1981), table 2.

[6] Charles Boutell, Boutell's Heraldry, revised by J. P. Brooke-Little (London and New York: Frederick Warne, 1978), p. 207.

[7] Sir Bernard Burke, A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Peerage and Baronetage (London: Harrison, 1885), p. cxxii.

[8] Burke’s Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Peerage and Baronetage (London: Burke’s Peerage, 1949), pp. ccliii-ccliv.

[9] Meaudre de Lapouyade, Les armoiries de Bordeaux (Bordeaux : Imprimerie Gounouilhou, 1913), p. 10. This work is found at: http://1886.u-bordeaux-montaigne.fr/viewer/show/3961#page/n4/mode/1up.

[10] Jacques Meurgey [de Tupigny], Notice historique sur les blasons des anciennes provinces de France (Paris: Compagnie française des arts graphiques, 1941), pp. 15, 50.

[11] G. Demay, Inventaire des sceaux de la Normandie (Paris: Imprimerie nationale, 1881), p. 8, no. 48.

[12] Michel Pastoureau and Michel Popoff, eds., L’Armorial Bellenville, (Lathuile: éditions du Gui, 2004), vol. 1 (introductory volume), p. 51, no. 10 and vol. 2 (the armorial itself), p. 1, no. 10. The armorial is dated in vol. 1, p. 8.

[13] The full description is: “Armoriaux, l'un du temps de « Loys, daulphin de Viennois, filz de Charles septiesme, » [plus tard Louis XI], l'autre de peu postérieur.” The folio is 13v.

[14] Emmanuel de Boos et al., L’armorial Le Breton (Paris: Somogy éditions d’art et al., 2004), p. 62 (6), no. 14 ; p. 65 (9), no. 71 and p. 74 (18), no. 136. Precisions as to what parts of the armorial belong to the fifteenth and thirteenth centuries are found on pp. 14-16. Although page 18 of the armorial is in the thirteenth century section it is deemed to belong to the fifteenth century.

[15] Meaudre de Lapouyade, Les armoiries de Bordeaux (1913), pp. 6-7.

[16] Ibid., pp. 10-11.

[17] Jacques Meurgey [de Tupigny], Notice historique sur les blasons des anciennes provinces de France, p. 50.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Michel Pastoureau and Michel Popoff, eds., L’Armorial Bellenville, vol. 1, p. 51, vol. 2, p. 1.

[20] Emmanuel de Boos et al., L’armorial Le Breton, p. 62 (6), no. 15 and p. 65 (9), no. 72.

We know that, beginning with the second equestrian seal of Richard I dated 1198, the Kings of England bore a shield with three gold lions on red. It was long believed that these lions were an addition of the two lions of Normandy with the one lion of Guyenne after the marriage of Henry II and Eleanor Duchess of Aquitaine in 1152, but there seems to be no concrete evidence to support this theory. On the other hand, there exists solid evidence that the Dukes of Normandy adopted two lions from the 1440’s. We also know that the single lion of the Kings of England as Dukes of Guyenne appeared on the seals and coins of Bordeaux in the early fourteenth century and possibly in the last quarter of the thirteenth century. Again there seems to be no evidence that such a lion was the emblem of Eleanor as Duchess of Aquitaine. In other words, the three lions of England were not the result of an addition of the two lions of Normandy with the single lion of Guyenne. In fact the documentation available demonstrates that the two lions of Normandy and the one lion of Guyenne were subtractions from the three lion of England to show the relationship between vassal and suzerain. This same type of subtraction was done to show the link between England and some Canadian colonies and provinces (figs. 8-14). It is somewhat like military ranks being designated by three, two, and one star depending on the rank.

Further reading – This article closely relates to the achievement of arms of Bordeaux whose single lion was long believed to be derived from the one attributed to Eleanor of Aquitaine. The history of the arms of Bordeaux does shed considerable light on the single lion of Aquitaine or Guyenne. As I progressed with this article, it became evident that the long and complex story of Bordeaux’s arms warranted an article of its own, see: The Achievement of Arms of Bordeaux: an Emblem Born in Strife.

Websites

All the websites cited in this article were consulted on 15 June 2016.

Notes

[1] Richard Marks and Ann Payne, British Heraldry from its Origins to c. 1800 (London: British Museum Publications, 1978), pp. 103, 109; Rodney Dennys, The Heraldic Imagination (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1976), pp. 30-31.

[2] Sir Bernard Burke, The General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales (London: Harrison, 1884), pp. lv-lvi.

[3] Jiří Louda, European Civic Coats of Arms (London: Paul Hamlyn, 1966), pp. 106-07.

[4] Stephen Friar, Heraldry (Stroud [Gloucestershire]: Sutton Publishing, 1996), pp. 232-33.

[5] Jiří Louda and Michael Maclagan, Heraldry of the Royal Families of Europe (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1981), table 2.

[6] Charles Boutell, Boutell's Heraldry, revised by J. P. Brooke-Little (London and New York: Frederick Warne, 1978), p. 207.

[7] Sir Bernard Burke, A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Peerage and Baronetage (London: Harrison, 1885), p. cxxii.

[8] Burke’s Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Peerage and Baronetage (London: Burke’s Peerage, 1949), pp. ccliii-ccliv.

[9] Meaudre de Lapouyade, Les armoiries de Bordeaux (Bordeaux : Imprimerie Gounouilhou, 1913), p. 10. This work is found at: http://1886.u-bordeaux-montaigne.fr/viewer/show/3961#page/n4/mode/1up.

[10] Jacques Meurgey [de Tupigny], Notice historique sur les blasons des anciennes provinces de France (Paris: Compagnie française des arts graphiques, 1941), pp. 15, 50.

[11] G. Demay, Inventaire des sceaux de la Normandie (Paris: Imprimerie nationale, 1881), p. 8, no. 48.

[12] Michel Pastoureau and Michel Popoff, eds., L’Armorial Bellenville, (Lathuile: éditions du Gui, 2004), vol. 1 (introductory volume), p. 51, no. 10 and vol. 2 (the armorial itself), p. 1, no. 10. The armorial is dated in vol. 1, p. 8.

[13] The full description is: “Armoriaux, l'un du temps de « Loys, daulphin de Viennois, filz de Charles septiesme, » [plus tard Louis XI], l'autre de peu postérieur.” The folio is 13v.

[14] Emmanuel de Boos et al., L’armorial Le Breton (Paris: Somogy éditions d’art et al., 2004), p. 62 (6), no. 14 ; p. 65 (9), no. 71 and p. 74 (18), no. 136. Precisions as to what parts of the armorial belong to the fifteenth and thirteenth centuries are found on pp. 14-16. Although page 18 of the armorial is in the thirteenth century section it is deemed to belong to the fifteenth century.

[15] Meaudre de Lapouyade, Les armoiries de Bordeaux (1913), pp. 6-7.

[16] Ibid., pp. 10-11.

[17] Jacques Meurgey [de Tupigny], Notice historique sur les blasons des anciennes provinces de France, p. 50.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Michel Pastoureau and Michel Popoff, eds., L’Armorial Bellenville, vol. 1, p. 51, vol. 2, p. 1.

[20] Emmanuel de Boos et al., L’armorial Le Breton, p. 62 (6), no. 15 and p. 65 (9), no. 72.