Chapter IV

THE QUEST FOR ARMS

The previous two chapters have largely dealt with heraldry’s struggle for survival in the face of false notions, prejudices, misconceptions, preconceived ideas, and the inroads of the logo at the expense of municipal and corporate heraldry. This chapter is dedicated to more positive aspects of the subject, namely how arms are inherited and the right approach to acquiring a proper grant if someone is not heir to ancestral arms.

Some enthusiastic genealogists are willing to perform considerable research in the hope of finding hereditary arms that they can claim. This is natural considering the frequently repeated axiom that heraldry and genealogy go hand in hand. Others suspect that they have ancestral arms stemming from a persistent rumour in the family or some extant armorial heirloom such as a bookplate, a ring or inherited silver. They want to investigate this further in the hope that a legitimate family coat of arms will be uncovered. Finally some prefer to design their own arms, sometimes leaving open the option of making them official at a future date. This chapter investigates the merits and drawbacks of each approach. Most petitioners for a grant from the Canadian Heraldic Authority are reasonably sure that no ancestral arms exist for their family, based on the origins and occupations of their ancestors or research into the matter. They therefore request a grant of original arms for themselves and their descendants.

Tracing Ancestral Arms

While researching ancestral arms, one may encounter heraldic descriptions called blazons, and to understand what they describe, the researcher will have to learn to acquire general notions of blazonry as outlined in Appendix I. The search for arms may well lead to various European countries. The path to follow in this eventuality is described in Appendix II which is focussed on North America, the British Isles and France as is the bibliography. For other countries, only general advice is offered, which is understandable given the many languages involved and the specificity of heraldic systems in each country. An excellent international bibliography by Michel Popoff is available on http://sfhs.free.fr/documents/biblio_internationale.pdf where works relating to a specific country can be found by entering appropriate search words. See also: http://www.heraldica.org/biblio/annotate.htm.

Before attempting to trace ancestral arms, it is necessary to know something about the descent of arms, at least in general terms. Traditionally in Europe arms descended in the male line. The eldest son received the undifferenced (without additions) arms and the juniors were generally required to place a distinctive mark on their shield. The husband could place the arms of his wife alongside his own on one shield, but the children did not automatically inherit the arms of the mother. This occurred only if the wife had no brothers and thus became an heiress or co-heiress. In such cases, the husband placed the shield of his wife in the centre of his own arms (an escutcheon of pretence), and though the husband had no personal right to the arms of his wife, the children inherited them quartered (repeated diagonally in two segments of the shield) with those of their father. In other words, as a general rule, women transmit arms when there is no male heir, that is when her own father is deceased and all the brothers and their descendants, male and female, have died. If there are several sisters, they become co-heiresses, all transmitting the father’s arms on an equal basis.

If the male line dies out, a descendant could claim the arms through a female line many years down the road, although that person would normally have a different family name. In some cases, a man marrying an heiress uses her name and arms. This happened several times in Canada’s history. For instance, the title and arms of Baron of Longueuil were transmitted to the Grant family by the marriage of Captain David Alexander Grant to the baroness Marie-Charles-Joseph LeMoyne de Longueuil who was heiress to both the title and arms. The baroness had gained recognition of her title by France in the 1770s and Queen Victoria recognized the title in 1880 in response to the claim of Charles Colmore Grant 7th Baron of Longueuil. [1]

Similarly Sir Henri-Gustave Joly de Lotbinière, prime-minister of Quebec 1878-79, became heir to the arms and name of Chartier de Lotbinière from his father Pierre-Gustave Joly, a Swiss citizen who married Julie-Christine in 1828, daughter and co-heiress of Michel-Eustache-Gaspard-Alain Chartier, Marquis de Lotbinière. His arms were recognized by letters patent of the College of Heralds on 30 June 1908. Above the shield is seen the coronet of a French marquis in reference to the ancestral title. [2] In these two cases, arms originating under the French Crown were given recognition by the English Crown.

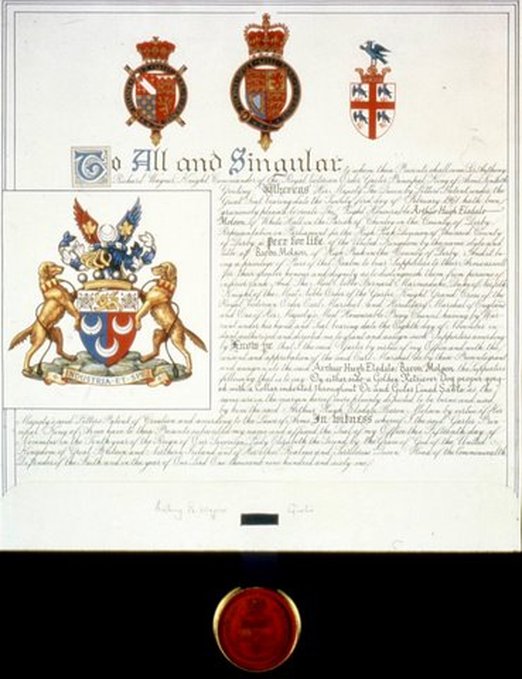

Tracing ancestral arms can, in some cases, be relatively simple. For instance, if your family was from England and you remember that your grandfather kept a patent of arms in his study with three red seals appended (example fig. 1) and called it his own grandfather’s patent―your own great-great-grandfather― there is a good chance that someone in the family has kept this document and that it can still be consulted. The document would tell you specifically to whom the arms were granted. If the document cannot be found, it should not be too difficult to have this confirmed by the College of Arms in England. A first enquiry should be made by providing your genealogy up to your great-great-grandfather. Claiming the actual arms would require legal documents proving descent in the male line. The process is similar to claiming an inheritance based on a will going several generations back. In both cases you have to produce solid proofs that you are the only heir or one of the heirs to whatever is contained in the will.

In the case described above, it may turn out that the great-great-grandfather was of the maternal line. In other words, your great-great-grandfather would be the father of your great-grandmother. If there were a number of great-granduncles in the maternal line you could only claim entitlement to the arms if all their descendants in both the male and female lines had become extinct with only the line of your great-grandmother surviving. If there were only great-granddaughters, they would all be co-heiresses to the arms, and the arms would have descended to your grandfather and finally to yourself. If the great-grandmother was the unique child, your grandfather would also have inherited the arms. To claim full arms without any difference, your grandfather, your father and yourself would all have to be the eldest male of each generation; otherwise, you would be entitled to a differenced version of the arms. Perhaps what is most important to retain is that proving entitlement to arms in the female line is generally far more complex than in the male line because of the way arms were inherited.

Proving descent from a more or less distant ancestor may turn out to be easy if a genealogy enthusiast has already delved into the matter, but failing this, months or even years of work can be involved. When going even a few generations back, an enormous amount of research may be required to prove that a line has become extinct and that the arms can be claimed by another line. In a sense, heraldry is a mirror of life itself where people marry sometimes several times, usually have children but sometimes not, where people die at varying ages and where a line can survive or become extinct. Ultimately the claim of entitlement to ancestral English arms through descent should receive confirmation from the College of Arms.

Some enthusiastic genealogists are willing to perform considerable research in the hope of finding hereditary arms that they can claim. This is natural considering the frequently repeated axiom that heraldry and genealogy go hand in hand. Others suspect that they have ancestral arms stemming from a persistent rumour in the family or some extant armorial heirloom such as a bookplate, a ring or inherited silver. They want to investigate this further in the hope that a legitimate family coat of arms will be uncovered. Finally some prefer to design their own arms, sometimes leaving open the option of making them official at a future date. This chapter investigates the merits and drawbacks of each approach. Most petitioners for a grant from the Canadian Heraldic Authority are reasonably sure that no ancestral arms exist for their family, based on the origins and occupations of their ancestors or research into the matter. They therefore request a grant of original arms for themselves and their descendants.

Tracing Ancestral Arms

While researching ancestral arms, one may encounter heraldic descriptions called blazons, and to understand what they describe, the researcher will have to learn to acquire general notions of blazonry as outlined in Appendix I. The search for arms may well lead to various European countries. The path to follow in this eventuality is described in Appendix II which is focussed on North America, the British Isles and France as is the bibliography. For other countries, only general advice is offered, which is understandable given the many languages involved and the specificity of heraldic systems in each country. An excellent international bibliography by Michel Popoff is available on http://sfhs.free.fr/documents/biblio_internationale.pdf where works relating to a specific country can be found by entering appropriate search words. See also: http://www.heraldica.org/biblio/annotate.htm.

Before attempting to trace ancestral arms, it is necessary to know something about the descent of arms, at least in general terms. Traditionally in Europe arms descended in the male line. The eldest son received the undifferenced (without additions) arms and the juniors were generally required to place a distinctive mark on their shield. The husband could place the arms of his wife alongside his own on one shield, but the children did not automatically inherit the arms of the mother. This occurred only if the wife had no brothers and thus became an heiress or co-heiress. In such cases, the husband placed the shield of his wife in the centre of his own arms (an escutcheon of pretence), and though the husband had no personal right to the arms of his wife, the children inherited them quartered (repeated diagonally in two segments of the shield) with those of their father. In other words, as a general rule, women transmit arms when there is no male heir, that is when her own father is deceased and all the brothers and their descendants, male and female, have died. If there are several sisters, they become co-heiresses, all transmitting the father’s arms on an equal basis.

If the male line dies out, a descendant could claim the arms through a female line many years down the road, although that person would normally have a different family name. In some cases, a man marrying an heiress uses her name and arms. This happened several times in Canada’s history. For instance, the title and arms of Baron of Longueuil were transmitted to the Grant family by the marriage of Captain David Alexander Grant to the baroness Marie-Charles-Joseph LeMoyne de Longueuil who was heiress to both the title and arms. The baroness had gained recognition of her title by France in the 1770s and Queen Victoria recognized the title in 1880 in response to the claim of Charles Colmore Grant 7th Baron of Longueuil. [1]

Similarly Sir Henri-Gustave Joly de Lotbinière, prime-minister of Quebec 1878-79, became heir to the arms and name of Chartier de Lotbinière from his father Pierre-Gustave Joly, a Swiss citizen who married Julie-Christine in 1828, daughter and co-heiress of Michel-Eustache-Gaspard-Alain Chartier, Marquis de Lotbinière. His arms were recognized by letters patent of the College of Heralds on 30 June 1908. Above the shield is seen the coronet of a French marquis in reference to the ancestral title. [2] In these two cases, arms originating under the French Crown were given recognition by the English Crown.

Tracing ancestral arms can, in some cases, be relatively simple. For instance, if your family was from England and you remember that your grandfather kept a patent of arms in his study with three red seals appended (example fig. 1) and called it his own grandfather’s patent―your own great-great-grandfather― there is a good chance that someone in the family has kept this document and that it can still be consulted. The document would tell you specifically to whom the arms were granted. If the document cannot be found, it should not be too difficult to have this confirmed by the College of Arms in England. A first enquiry should be made by providing your genealogy up to your great-great-grandfather. Claiming the actual arms would require legal documents proving descent in the male line. The process is similar to claiming an inheritance based on a will going several generations back. In both cases you have to produce solid proofs that you are the only heir or one of the heirs to whatever is contained in the will.

In the case described above, it may turn out that the great-great-grandfather was of the maternal line. In other words, your great-great-grandfather would be the father of your great-grandmother. If there were a number of great-granduncles in the maternal line you could only claim entitlement to the arms if all their descendants in both the male and female lines had become extinct with only the line of your great-grandmother surviving. If there were only great-granddaughters, they would all be co-heiresses to the arms, and the arms would have descended to your grandfather and finally to yourself. If the great-grandmother was the unique child, your grandfather would also have inherited the arms. To claim full arms without any difference, your grandfather, your father and yourself would all have to be the eldest male of each generation; otherwise, you would be entitled to a differenced version of the arms. Perhaps what is most important to retain is that proving entitlement to arms in the female line is generally far more complex than in the male line because of the way arms were inherited.

Proving descent from a more or less distant ancestor may turn out to be easy if a genealogy enthusiast has already delved into the matter, but failing this, months or even years of work can be involved. When going even a few generations back, an enormous amount of research may be required to prove that a line has become extinct and that the arms can be claimed by another line. In a sense, heraldry is a mirror of life itself where people marry sometimes several times, usually have children but sometimes not, where people die at varying ages and where a line can survive or become extinct. Ultimately the claim of entitlement to ancestral English arms through descent should receive confirmation from the College of Arms.

Fig. 1 Grant of arms to Sarah Ellen Pignatore née Molson and to the descendants of John Molson, 7 Sept. 1934, by Kings of Arms of England. Library and Archives Canada, negative C 127982.

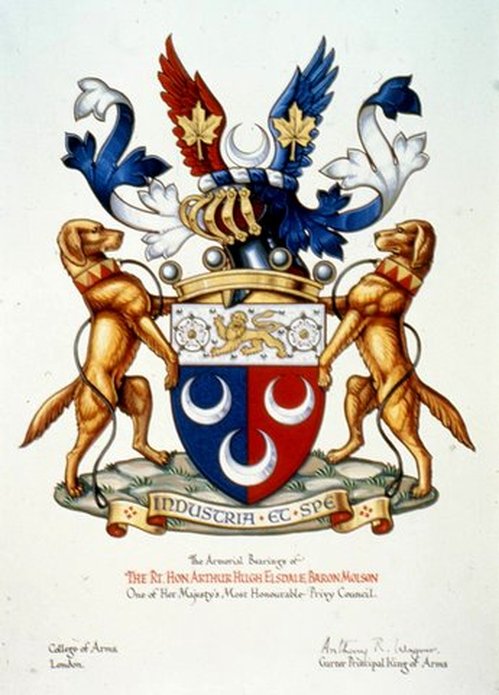

Fig. 2 Grant of supporters under Garter’s seal to the Right Honourable Arthur Hugh Elsdale Baron Molson, great-great-grandson of the Honourable John Molson the elder of Montreal. Library and Archives Canada, negative C 127983.

Fig. 3 Exemplification of the arms of the Right Honourable Arthur Hugh Elsdale Baron Molson, Library and Archives Canada.

If a claimant came to the Chief Herald of Canada with the actual granting patent and solid proof of senior descent from the grantee in the male line, the incumbent of the office might, on a discretionary basis, proceed with a registration, but if the grant went too far back or something was unclear in the line of descent, a new grant would no doubt be required with certain modifications to the arms. Again the petitioner would have to prove descent from the ancestral armiger with proper documentation such as birth certificates, civil registrations, marriage certificates or registrations, wills and other legal documents such as land or property transactions, census records, church records relating to birth, baptism, marriage and burial. Even an inscription on a tombstone could constitute concrete proof of lineage. Of course, every case has its own particularities and the ultimate decision in such matters in Canada rests with the Chief Herald of Canada.

Some Canadians are descended from a Scottish ancestor who was granted arms by Lord Lyon. In Scotland it is unlawful for descendants to use such arms without being assigned appropriate modifications that are recorded every generation in the Public Register of All Arms and Bearings in Scotland. If a Canadian of Scottish origin could prove entitlement to ancestral arms and wanted to record them in Canada, the Chief Herald would have no option but to proceed with a differenced grant of the arms or an entirely new grant. In Canada arms belong to one person and to descendants with proper differences. Clan arms of Irish, Polish or Hungarian origin would also have to be differenced, as would, in most cases, a number of authentic arms granted to Canadians at the time of New France.

The arms of Pierre Boucher, Sieur de Grosbois, were clearly assigned to him on 26 April 1708 by Charles d’Hozier, Judge of Arms of France and Keeper of the Armorial (juge d’armes de France et garde de l’Armorial). There is surely someone who is entitled to the full arms based on descent in the senior male line, but this would no doubt be hard to prove, though perhaps not impossible. Because marks of difference in France were not frequently enforced, one could argue that all the descendants would be entitled to the full arms. This, however, would not be compatible with the Canadian system of one coat of arms for one person, in the sense that the arms descend to one person without differences and the others are entitled to modified arms. The Boucher descent is considerable and, like many noble families, has branched out into many names like Boucherville, Grandpré, Grosbois, La Bruère, La Perrière, Montarville, Montbrun, and Montizambert. All of the descendants of these branches should be able to obtain a differenced Canadian version of the original arms with proof that they are descended from the original Boucher.

If a document relating to arms is found in family archives or during genealogical research, it has to be closely examined to determine whether it has any legitimacy. It can easily be from a completely bogus source or from a source that is not authorized to grant arms. In Canada a number of well-intentioned persons, acting on their own, set themselves up as a sort of registry office or college and began recording genealogies and arms. They understood that genealogy and heraldry were twin sciences, and the underlying goal was to preserve both family and armorial heritage by recording them for posterity. However, their attribution of arms to specific families often lacked the required scientific rigor. Also, some artists began creating entirely new arms in response to an existing need, sometimes because their clients were unwilling to go overseas, but more often because they did not even know of such possibilities.

One of the first persons to labour for the preservation of Canada’s armorial heritage was a man who styled himself Frédéric Gregory Forsyth, Vicomte de Fronsac. Forsyth was an American who came to Canada in 1893 and set up on his own authority what he styled a Canadian College of Arms. His college took on many pompous titles, the more modest ones being “College of Arms of Canada” but also “College of Arms of the Noblesse in Canada” and “Aryan Order College of Arms in Canada”.

The “Vicomte” attempted to bring together the nobility of America, to record their titles and arms in his college as well as to provide families with certificates of registration, genealogies and copies of arms. In some cases, the arms registered by Fronsac were authentic, but in other cases, the evidence was quite flimsy. Be that as it may, it is important to remember that Fronsac’s college had no official status and therefore no authority to make arms authentic. If one finds in family papers certificates or documentation relating to arms issued by Fronsac’s college, they have to be examined with the greatest care. If the arms in question came from England, Scotland or Ireland, any claim made by Fronsac would have to be checked with the existing heraldic authorities of these countries. [3]

Another heraldic college was the Collège héraldique of the Société historique de Montréal, which came into existence around 1915. Again the arms created by this college had no official status and those it registered were not necessarily arms that had been previously granted by a recognized authority, even though the president of the College was Victor Morin, a well-known francophone heraldist. One case in point is the arms of Sir Wilfrid Laurier. As a G.C.M.G. (Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St. Michael and St. George), Laurier would normally have obtained properly granted arms from the Heralds of England, but he had no interest in the matter. An amateur heraldist named Étienne-Eugène Taché, architect of the Quebec Parliament Buildings, eventually produced arms for him that were registered by the Collège héraldique. The arms were well designed, but registering them in the College did not make them more legitimate, since the college had no mandate from the Crown to grant arms. [4]

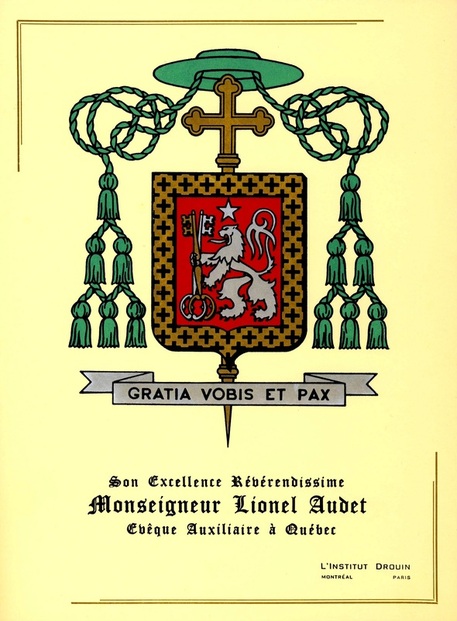

Two other institutions that were active in creating arms for francophone individuals and municipalities were the Institut généalogique Drouin created in 1899, and the Collège canadien des armoiries that worked in Montreal during the 1950s. Both these private companies produced instances of good heraldry, but again they had no mandate to give these arms any official status (fig. 4).

Some Canadians are descended from a Scottish ancestor who was granted arms by Lord Lyon. In Scotland it is unlawful for descendants to use such arms without being assigned appropriate modifications that are recorded every generation in the Public Register of All Arms and Bearings in Scotland. If a Canadian of Scottish origin could prove entitlement to ancestral arms and wanted to record them in Canada, the Chief Herald would have no option but to proceed with a differenced grant of the arms or an entirely new grant. In Canada arms belong to one person and to descendants with proper differences. Clan arms of Irish, Polish or Hungarian origin would also have to be differenced, as would, in most cases, a number of authentic arms granted to Canadians at the time of New France.

The arms of Pierre Boucher, Sieur de Grosbois, were clearly assigned to him on 26 April 1708 by Charles d’Hozier, Judge of Arms of France and Keeper of the Armorial (juge d’armes de France et garde de l’Armorial). There is surely someone who is entitled to the full arms based on descent in the senior male line, but this would no doubt be hard to prove, though perhaps not impossible. Because marks of difference in France were not frequently enforced, one could argue that all the descendants would be entitled to the full arms. This, however, would not be compatible with the Canadian system of one coat of arms for one person, in the sense that the arms descend to one person without differences and the others are entitled to modified arms. The Boucher descent is considerable and, like many noble families, has branched out into many names like Boucherville, Grandpré, Grosbois, La Bruère, La Perrière, Montarville, Montbrun, and Montizambert. All of the descendants of these branches should be able to obtain a differenced Canadian version of the original arms with proof that they are descended from the original Boucher.

If a document relating to arms is found in family archives or during genealogical research, it has to be closely examined to determine whether it has any legitimacy. It can easily be from a completely bogus source or from a source that is not authorized to grant arms. In Canada a number of well-intentioned persons, acting on their own, set themselves up as a sort of registry office or college and began recording genealogies and arms. They understood that genealogy and heraldry were twin sciences, and the underlying goal was to preserve both family and armorial heritage by recording them for posterity. However, their attribution of arms to specific families often lacked the required scientific rigor. Also, some artists began creating entirely new arms in response to an existing need, sometimes because their clients were unwilling to go overseas, but more often because they did not even know of such possibilities.

One of the first persons to labour for the preservation of Canada’s armorial heritage was a man who styled himself Frédéric Gregory Forsyth, Vicomte de Fronsac. Forsyth was an American who came to Canada in 1893 and set up on his own authority what he styled a Canadian College of Arms. His college took on many pompous titles, the more modest ones being “College of Arms of Canada” but also “College of Arms of the Noblesse in Canada” and “Aryan Order College of Arms in Canada”.

The “Vicomte” attempted to bring together the nobility of America, to record their titles and arms in his college as well as to provide families with certificates of registration, genealogies and copies of arms. In some cases, the arms registered by Fronsac were authentic, but in other cases, the evidence was quite flimsy. Be that as it may, it is important to remember that Fronsac’s college had no official status and therefore no authority to make arms authentic. If one finds in family papers certificates or documentation relating to arms issued by Fronsac’s college, they have to be examined with the greatest care. If the arms in question came from England, Scotland or Ireland, any claim made by Fronsac would have to be checked with the existing heraldic authorities of these countries. [3]

Another heraldic college was the Collège héraldique of the Société historique de Montréal, which came into existence around 1915. Again the arms created by this college had no official status and those it registered were not necessarily arms that had been previously granted by a recognized authority, even though the president of the College was Victor Morin, a well-known francophone heraldist. One case in point is the arms of Sir Wilfrid Laurier. As a G.C.M.G. (Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St. Michael and St. George), Laurier would normally have obtained properly granted arms from the Heralds of England, but he had no interest in the matter. An amateur heraldist named Étienne-Eugène Taché, architect of the Quebec Parliament Buildings, eventually produced arms for him that were registered by the Collège héraldique. The arms were well designed, but registering them in the College did not make them more legitimate, since the college had no mandate from the Crown to grant arms. [4]

Two other institutions that were active in creating arms for francophone individuals and municipalities were the Institut généalogique Drouin created in 1899, and the Collège canadien des armoiries that worked in Montreal during the 1950s. Both these private companies produced instances of good heraldry, but again they had no mandate to give these arms any official status (fig. 4).

Fig.4 An example of the work of l’Institut Drouin, print 1952, property of A. & P. Vachon.

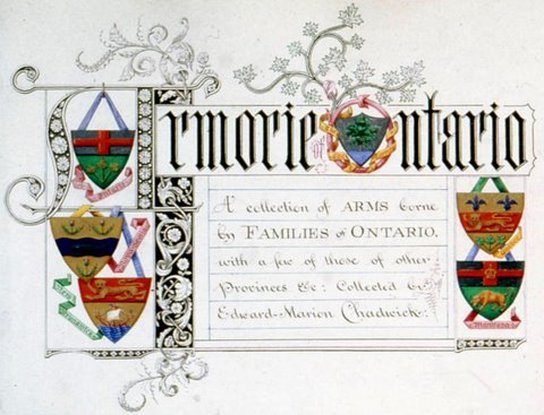

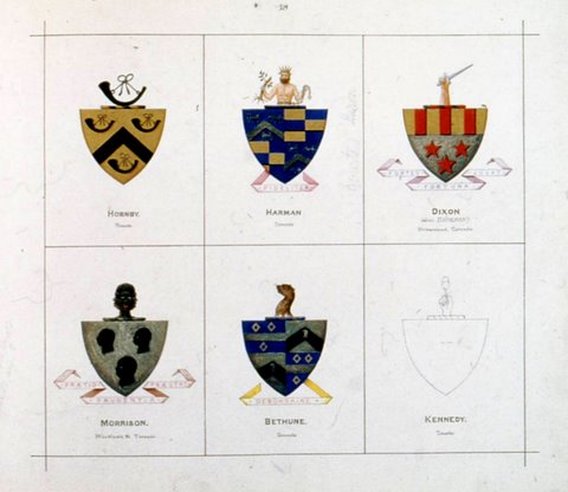

Heraldry in Ontario has been marked by the work of the genealogist and heraldist Edward Marion Chadwick, a Toronto lawyer. As author of Ontarian Families and of the quarterly The Ontario Genealogist and Family Historian, he attributed arms to many families (figs. 5-6), but each case requires close verification, all the more so that Chadwick sometimes took liberties with heraldry. [5]

Fig. 5 “ARMORIE of ONTARIO: A collection of ARMS borne by FAMLIES of ONTARIO with a few of those of other Provinces etc: Collected by Edward Marion Chadwick,” Library and Archives Canada, negative C 128097.

Fig. 6 Page 18 from Chadwick’s unfinished ARMORIE of ONTARIO, Library and Archives Canada.

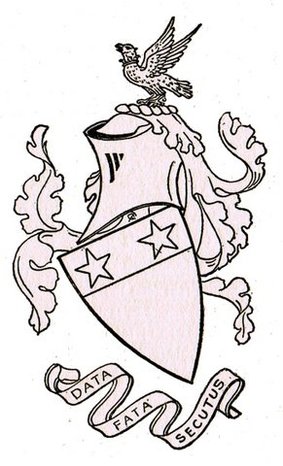

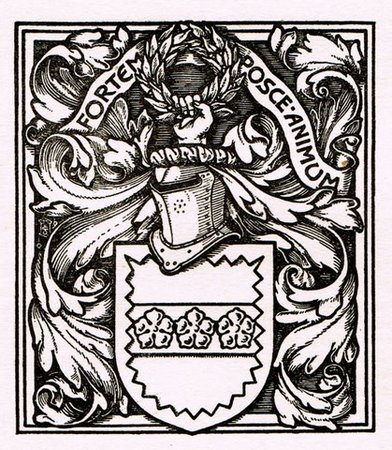

Herbert George Todd, a mechanical engineer born in Quebec and living in Yonkers (New York), produced several editions of a work entitled Armory and Lineages of Canada dated 1913 to 1919. Again some of the arms are authentic such as those he describes for Walter Reginald Baker of Montreal, John Charles Alison Heriot of Montreal, Edward Æmilius Jarvis of Toronto, St. Andrew St. John of Orillia (figs. 7-10). These arms are accompanied by substantial genealogies and clearly demonstrate that a number of families, sometimes living in small communities, are entitled to arms because one of their ancestors took steps to obtain properly granted arms. Others require further research, all the more so that the author does not give any information as to their source. Some are obviously incorrect, as when he attributes to Governor General Monk a wyvern (two legs) instead of a dragon (four legs) as dexter supporter and, to Governor Louis Buade de Frontenac, three gold griffins on a blue field instead of three gold griffins legs on blue. The arms he attributes to General James Wolfe and to Robert Cavelier de La Salle are likewise completely erroneous. [6]

|

Fig. 7 Arms of Walter Reginald Baker of Montreal, granted by Kings of Arms of England, 1912. Fig. 9 Arms of St. Andrew St. John of Orillia, attributed by descent from the 10th Baron of St. John.

|

Fig. 8 Arms of Edward Æmilius Jarvis of Toronto, granted by Kings of Arms of England, 25 October 1915.

Fig. 10 Arms of John Charles Alison Heriot of Montreal, granted by Lord Lyon King of Arms, 29 April 1905. |

In the 1970s the federal government promoted a number of multi-cultural programmes, some of which were initiated at the National Archives of Canada. At that time Hans Dietrich Birk was hired on contract to document the arms of families of European origin other than those from the British Isles or France, and to ensure that this information was preserved for posterity (figs. 11-12). His efforts were published in the work entitled Birk’s Armorial Heritage in Canada. [7] The work is helpful as it gives some family history and the place of residence of the family claiming the arms at the time of publication. In every case, Birk has verified these claims using many printed sources and, in some cases, from the actual granting document still extant in the family. Of course Birk’s publication and the fact that his working files are held by Library and Archives Canada, does not make the arms official in Canada. No matter how ancient and dignified in their country of origin, the arms can only be made official in Canada by being confirmed by the Canadian Heraldic Authority in a registration or grant, usually with proper differences making them unique to the grantee.

The only two persons in Canada to have held government positions relating specifically to heraldry prior to the creation of the Canadian Heraldic Authority were Maurice Brodeur who signed his letters as Chef du service héraldique, Secrétariat de la province (province of Quebec) in the 1950s, and myself who was responsible for heraldic collections at the National Archives of Canada from 1967 to 1988. Brodeur was active in designing a large number of coats of arms including those of Lieutenant Governors Gaspard Fauteux and Eugène Fiset, none of which had official status. While my own role was to preserve heraldic documentation and reply to questions from the public relating to armorial matters, my advice was sought for about a dozen designs. Some came out well and others were acceptable, but in many cases, the creator was mostly seeking approval for a fait accompli. All these designs were without official status because they were not grants from the Crown. Nevertheless, these experiences do bring home the fact that a heraldic authority cannot just be an advisory body if it is to function properly. It has to be a granting body that is able to control what is granted.

Over the years, a number of heraldists and artists have produced arms particularly for individuals and cities, a few of which were good, many not so good and quite a few not heraldic at all. Although these creations have acquired a certain historical dimension, they are not granted by heraldic officers of the Crown, and therefore, again, have no official status. [8]

Canada is composed of immigrants from many European countries that have a heraldic system or have had one in the past. These systems differ from one country to another and, to have a historic right to such ancestral arms, one must still prove this by descent or lineage and in conformity with the heraldic system of a given country (see appendix II). Here again there is no easy solution when claiming ancestral emblems and only serious research can provide reliable results.

Any way we look at it, researching ancestral arms requires patience and a scientific approach. It is also important to realize that even the most exhaustive research may not yield results. A sound attitude is to get involved for genealogical reasons, and hope that the research will lead to the discovery of arms that one can claim. Being reasonably sure that one does not have ancestral arms following serious research is also valuable information. One should also be guided by common sense. If your ancestor came from Great Britain or France as an artisan or laborer, the chances of finding ancestral arms are not very good. A person having found authentic ancestral arms could use them based on a historical right, but it would be better still to approach the heraldic authority of the country where one lives, if such a body exists, to obtain clear undisputed property of the arms based on a registration or a differenced grant.

Family Heirlooms and Other Evidence

Some persons approach the Canadian Heraldic Authority claiming that they have arms that have been in use for generations. Others may speak of a persistent rumour within the family concerning ancestral arms or may claim that one of their relatives has succeeded in tracing the family’s arms. When faced with such situations, heralds might be tempted to say, “If you have arms, why are you coming to me?” But this would not be helpful. In such cases, the inquirer usually has doubts concerning the validity of the arms and believes that heralds can easily verify this in some form of register or by computer. But authenticating arms, or finding out what family they belong to, requires a lot of genealogical work and may involve going back to the country of origin of the family where the arms were presumably granted. Arms do not belong to a name! They belong originally to one person and are inherited by that person’s descendants somewhat like other types of property as we have seen. Because of the amount of research required, the onus is really upon the claimant to prove entitlement to the arms.

If a relative claims to have found the family arms, it is necessary to ask that person to provide an illustration or heraldic description of the emblem and the genealogical proof that it belongs to the family lineage. With the information in hand, a herald would be able to better judge if there is any legitimacy to the claim. If it turns out to be based on authentic documentation, all the better! Unfortunately the source of such arms is often an armorial (book of arms) which provides little genealogical information or even a certificate sold by a peddler of arms, which has no validity.

Even in cases where considerable genealogical work has been done, it often turns out that genealogists are less rigorous in heraldic matters than they are in genealogical research. Ideally proof of entitlement to ancestral arms is established by a reliable source demonstrating beyond any doubt that the arms were indeed officially granted to a specific ancestor, and that the claimant is descended from that ancestor, usually in the male line. Such documents, in ideal circumstances, would be the granting document itself and proof of descent from the grantee or a letter from the official granting authority stating that the proofs to entitlement are valid, based on the genealogy and information drawn from its records. In many cases, the only information available is that families or clans of the same name bore certain arms in the region from where the ancestor immigrated.

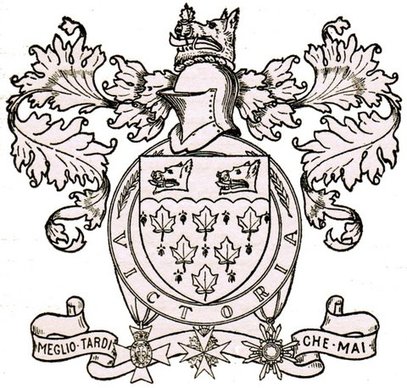

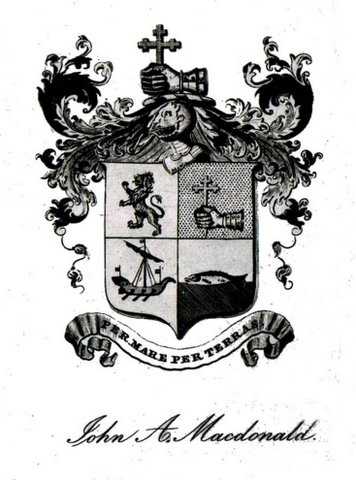

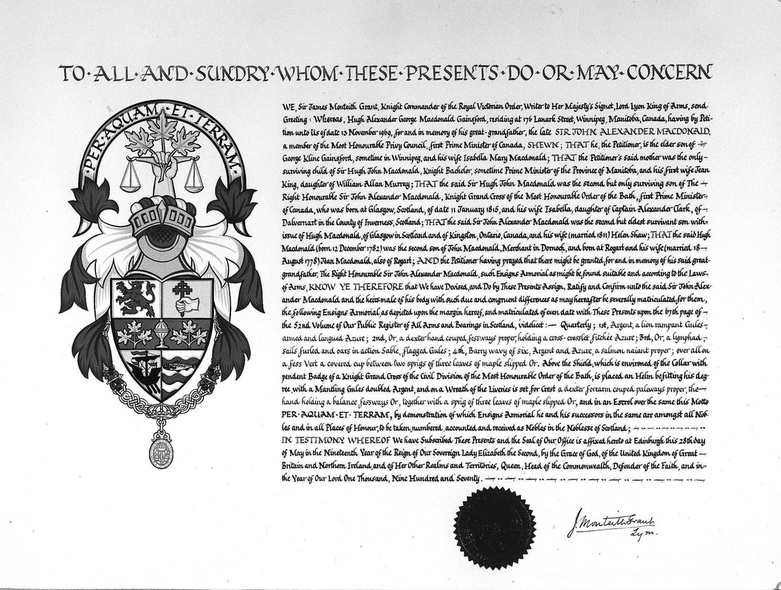

In other instances, the claim is based on a family heirloom such as silverware, a ring or a bookplate decked with arms. Such indications are well worth following up, but do not as such constitute proof of entitlement. During his lifetime, Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald used the arms of clan Macdonald of Sleat to which he was not entitled, for instance on his bookplate and silver. The idea of obtaining proper arms for the first prime minister was promoted by Clan Donald. Following a petition by his great-grandson, Alexander George Macdonald Gainsford of Winnipeg, Lord Lyon King of Arms granted armorial bearings to Sir John A. and his descendants (“the heirs male of his body”) by letters patent dated 28 May 1970 (figs. 13-15). [9] These arms were later registered by the Canadian Heraldic Authority.

Over the years, a number of heraldists and artists have produced arms particularly for individuals and cities, a few of which were good, many not so good and quite a few not heraldic at all. Although these creations have acquired a certain historical dimension, they are not granted by heraldic officers of the Crown, and therefore, again, have no official status. [8]

Canada is composed of immigrants from many European countries that have a heraldic system or have had one in the past. These systems differ from one country to another and, to have a historic right to such ancestral arms, one must still prove this by descent or lineage and in conformity with the heraldic system of a given country (see appendix II). Here again there is no easy solution when claiming ancestral emblems and only serious research can provide reliable results.

Any way we look at it, researching ancestral arms requires patience and a scientific approach. It is also important to realize that even the most exhaustive research may not yield results. A sound attitude is to get involved for genealogical reasons, and hope that the research will lead to the discovery of arms that one can claim. Being reasonably sure that one does not have ancestral arms following serious research is also valuable information. One should also be guided by common sense. If your ancestor came from Great Britain or France as an artisan or laborer, the chances of finding ancestral arms are not very good. A person having found authentic ancestral arms could use them based on a historical right, but it would be better still to approach the heraldic authority of the country where one lives, if such a body exists, to obtain clear undisputed property of the arms based on a registration or a differenced grant.

Family Heirlooms and Other Evidence

Some persons approach the Canadian Heraldic Authority claiming that they have arms that have been in use for generations. Others may speak of a persistent rumour within the family concerning ancestral arms or may claim that one of their relatives has succeeded in tracing the family’s arms. When faced with such situations, heralds might be tempted to say, “If you have arms, why are you coming to me?” But this would not be helpful. In such cases, the inquirer usually has doubts concerning the validity of the arms and believes that heralds can easily verify this in some form of register or by computer. But authenticating arms, or finding out what family they belong to, requires a lot of genealogical work and may involve going back to the country of origin of the family where the arms were presumably granted. Arms do not belong to a name! They belong originally to one person and are inherited by that person’s descendants somewhat like other types of property as we have seen. Because of the amount of research required, the onus is really upon the claimant to prove entitlement to the arms.

If a relative claims to have found the family arms, it is necessary to ask that person to provide an illustration or heraldic description of the emblem and the genealogical proof that it belongs to the family lineage. With the information in hand, a herald would be able to better judge if there is any legitimacy to the claim. If it turns out to be based on authentic documentation, all the better! Unfortunately the source of such arms is often an armorial (book of arms) which provides little genealogical information or even a certificate sold by a peddler of arms, which has no validity.

Even in cases where considerable genealogical work has been done, it often turns out that genealogists are less rigorous in heraldic matters than they are in genealogical research. Ideally proof of entitlement to ancestral arms is established by a reliable source demonstrating beyond any doubt that the arms were indeed officially granted to a specific ancestor, and that the claimant is descended from that ancestor, usually in the male line. Such documents, in ideal circumstances, would be the granting document itself and proof of descent from the grantee or a letter from the official granting authority stating that the proofs to entitlement are valid, based on the genealogy and information drawn from its records. In many cases, the only information available is that families or clans of the same name bore certain arms in the region from where the ancestor immigrated.

In other instances, the claim is based on a family heirloom such as silverware, a ring or a bookplate decked with arms. Such indications are well worth following up, but do not as such constitute proof of entitlement. During his lifetime, Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald used the arms of clan Macdonald of Sleat to which he was not entitled, for instance on his bookplate and silver. The idea of obtaining proper arms for the first prime minister was promoted by Clan Donald. Following a petition by his great-grandson, Alexander George Macdonald Gainsford of Winnipeg, Lord Lyon King of Arms granted armorial bearings to Sir John A. and his descendants (“the heirs male of his body”) by letters patent dated 28 May 1970 (figs. 13-15). [9] These arms were later registered by the Canadian Heraldic Authority.

Fig. 15 Grant of arms to Sir John A. Macdonald by the Lyon King of arms in 1970. The patent of arms is kept by Library and Archives Canada, negative C 23322. See registration by Canadian Heraldic Authority: http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=2392&ShowAll=1.

At times inquirers are simply looking for arms to decorate their family tree. That is a legitimate quest and indeed, if you expand your family tree into many lateral lines, you may well find several ancestors who were entitled to arms. These can be included in a family tree beside the name of the armiger, but one cannot use them personally, unless directly descended from the person in question.

In some cases, persons claim to be descended from a titled family. If the ancestral title is authentic, arms are likely to be associated with it. However, this is not always the case. A number of Canadians with titles of knighthood did not take time to have official arms recorded. Perhaps the most prominent names are Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir Wilfrid Laurier, but there are many others. Of the numerous Sirs recorded in dictionaries of Canadian biography, very few are known to have possessed granted arms. Researching the Canadian “Sirs” who bore arms and those that did not would be a mammoth task but a most valuable contribution to heraldic knowledge.

Similar situations existed for some persons ennobled at the time of New France. For instance, Mathieu Amiot dit Villeneuve received letters of nobility in 1668, but Intendant Talon did not know whether to register them with the Conseil Souverain at Quebec or with the Parliament in Paris. By the time he received an answer, Louis XIV had abolished all unregistered titles and Amiot made no effort to have his title recognized as others successfully did. [10] Since the right to be granted arms was based on his letters of nobility, when these were invalidated, the right to obtain granted arms was voided at the same time. It is important to describe in some details situations dating back to the French Regime in Canada because so many Canadians all across the country as well as Americans, often speaking English only, are of French origin and information on the subject in English is not easy to come by.

A persistent idea is that if your ancestor was a seigneur at the time of New France, he was automatically a noble. While some seigneurs were nobles, many were not. Only eleven land grants at the time of New France were titled lands: two marquisates, two counties, two baronies, and one châtellenie. Moreover, the acquisition of titled land did not automatically transfer the title to the owner. If a noble acquired titled land, the authorization of the sovereign was still required to bear the title attached to the land. Furthermore, a commoner was not authorized to use the title attached to newly acquired land. Only the designation of seigneur was allowed and this was not a title of nobility. [11]

One title often claimed for an ancestor is that of chevalier, meaning knight in English. Chevalier is a title in itself to which less than 300 families in France are entitled. It belongs to descendants from the old knightly nobility. [12] The orders of the Kings of France included the rank of chevalier and indeed most of the members of these orders were nobles and would normally have been granted arms. On the other hand, the Order of Saint-Louis was opened to commoners who in some rare cases would not have been armigerous (entitled to arms). But these cases are rare, since most officers were nobles, and nobles remained a majority in the Order of Saint-Louis. [13]

The Legion of Honour, created at the time of Napoleon, was opened to all classes of society and its members were granted arms, but Napoleon’s heraldic system was abandoned in 1815 following the Restoration, as were the automatic grants to members of the Legion. The arms granted at the time of Napoleon are well documented; see https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Armorial_du_Premier_Empire#Bibliographie especially section 8.1 “Notes et références.” Many titles of chevalier today do not convey any notion of nobility. Chevalier de l’Ordre national du Québec, Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur, Chevalier de l’Ordre de Pie IX, Chevalier de l’ordre de la Pléade, Chevalier de l’ordre de la Palme académique are all authentic titles, but none of them confer nobility. Various types of societies also use the designation of chevalier as do the Chevaliers de Colomb (Knights of Columbus). Therefore if someone is addressed as chevalier, it rarely means descent from nobility. Again, caution is in order!

If your ancestor was an officer in the French army or navy at the time of New France, chances are very good that he was armigerous, since most officers were drawn from the nobility. But this should only serve as a guideline since there are exceptions to this general rule. A case in point is Charles Daniel who was a sea captain (a senior officer) in New France, long before the king ennobled him in 1648. Had he not been ennobled or deceased before being ennobled, he would not normally have been entitled to granted arms although he had served for many years as an officer. The same is true of Joseph-François de la Fresnière who, although made a lieutenant in 1696 and a captain in 1712, only received letters of nobility and a proper grant of arms in 1716. [14]

During the period of New France, the king ennobled eleven worthy Canadians and some noble families settled in the colony. But nobles were a very small percentage of the population, in fact about 100 families in 1767. [15] If you can prove that you are descended from one of these nobles and can identify their coat of arms, you certainly have an historic claim to the arms. France today is a republic and does not give official recognition to arms. But if you are a Canadian descended from a French armigerous ancestor, the Chief Herald of Canada would be able to grant you the old arms with adequate marks of difference added to make them specific to yourself.

There is no doubt that there are other families of French origin whose ancestors made use of bourgeois arms, but they are not numerous in Canada. [16] In fact such claims are most difficult to prove. French sources frequently state that a family in a particular area bore such and such arms and this is really too vague to constitute a proof of entitlement for a person living today. Indeed, proof may be almost impossible in the case of the arms of commoners, particularly if they precede1696 when such arms began to be registered. But anyone who seriously and with scientific rigor searches for ancestral arms through genealogy and historical documentation cannot be faulted, even if the search should prove inconclusive. In many cases, heraldic authorities will grant elements of the arms traditionally used by families in a specific area of a country if the ancestors of the petitioner originate from that area.

Assumed Arms

In some cases, persons will design their own original arms or have them designed by an amateur heraldist. That approach is not illegal and is more honest than taking someone else’s arms from a published work based only on a family name.

On the other hand, such arms do not necessarily respect some of the fundamental rules of heraldry and are sometimes drawn contrary to its aesthetics. If such arms begin appearing on bookplates, rings and other family heirlooms, descendants are easily convinced that they are true authentic emblems. Over time one of the descendants is bound to discover, with some disappointment, that the arms used for many years or by several generations by his family have no official status and cannot be made official in the form in which they were designed.

It takes years of study and practice to become a competent lawyer, engineer or doctor. Similarly it takes many years of study and practice to become competent in heraldry. While heralds should possess a good knowledge of history, mythology and a broad general culture allowing them to design beautiful and significant heraldry, they do not necessarily have any artistic talent. They usually have to call upon an artist able to depict coats of arms with the beauty they warrant. Conversely artists may not possess the historical knowledge required to create significant arms. Only a few persons can do both. That is why heraldic authorities work as a team of highly skilled specialists. From this point of view, it is pretentious for an individual to think of creating good heraldry overnight or that a friend with artistic ability will put a design into proper form. Even a person highly skilled in drawing and painting requires a period of study and practice to become a successful heraldic artist.

Grants by Metropolitan Authorities

At the time of New France, nobles who settled in Canada brought their own arms with them, but grants of arms to persons living in Canada were very few. We know that, of the eleven Canadians ennobled by the sovereign, at least ten had arms. The edict of 1696 did not apply to New France, but possibly a few Canadians were in France at the time the edict was in force and obtained arms via that route (fig. 16). After Canada had been conquered in 1759, at least one Canadian had armorial dealings with France. In 1761 Pierre Raimbault de Simblim obtained arms from the judge of arms Louis-Pierre d’Hozier for his father Paul, a seigneur but apparently not a noble. In 1787 Michel Chartier de Lotbinière had his ancestral arms modified by the Judge of Arms Antoine-Marie d’Hozier de Sérigny. [17] An estimate of the total French grants to Canadians would be about a dozen, possibly a little more.

In some cases, persons claim to be descended from a titled family. If the ancestral title is authentic, arms are likely to be associated with it. However, this is not always the case. A number of Canadians with titles of knighthood did not take time to have official arms recorded. Perhaps the most prominent names are Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir Wilfrid Laurier, but there are many others. Of the numerous Sirs recorded in dictionaries of Canadian biography, very few are known to have possessed granted arms. Researching the Canadian “Sirs” who bore arms and those that did not would be a mammoth task but a most valuable contribution to heraldic knowledge.

Similar situations existed for some persons ennobled at the time of New France. For instance, Mathieu Amiot dit Villeneuve received letters of nobility in 1668, but Intendant Talon did not know whether to register them with the Conseil Souverain at Quebec or with the Parliament in Paris. By the time he received an answer, Louis XIV had abolished all unregistered titles and Amiot made no effort to have his title recognized as others successfully did. [10] Since the right to be granted arms was based on his letters of nobility, when these were invalidated, the right to obtain granted arms was voided at the same time. It is important to describe in some details situations dating back to the French Regime in Canada because so many Canadians all across the country as well as Americans, often speaking English only, are of French origin and information on the subject in English is not easy to come by.

A persistent idea is that if your ancestor was a seigneur at the time of New France, he was automatically a noble. While some seigneurs were nobles, many were not. Only eleven land grants at the time of New France were titled lands: two marquisates, two counties, two baronies, and one châtellenie. Moreover, the acquisition of titled land did not automatically transfer the title to the owner. If a noble acquired titled land, the authorization of the sovereign was still required to bear the title attached to the land. Furthermore, a commoner was not authorized to use the title attached to newly acquired land. Only the designation of seigneur was allowed and this was not a title of nobility. [11]

One title often claimed for an ancestor is that of chevalier, meaning knight in English. Chevalier is a title in itself to which less than 300 families in France are entitled. It belongs to descendants from the old knightly nobility. [12] The orders of the Kings of France included the rank of chevalier and indeed most of the members of these orders were nobles and would normally have been granted arms. On the other hand, the Order of Saint-Louis was opened to commoners who in some rare cases would not have been armigerous (entitled to arms). But these cases are rare, since most officers were nobles, and nobles remained a majority in the Order of Saint-Louis. [13]

The Legion of Honour, created at the time of Napoleon, was opened to all classes of society and its members were granted arms, but Napoleon’s heraldic system was abandoned in 1815 following the Restoration, as were the automatic grants to members of the Legion. The arms granted at the time of Napoleon are well documented; see https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Armorial_du_Premier_Empire#Bibliographie especially section 8.1 “Notes et références.” Many titles of chevalier today do not convey any notion of nobility. Chevalier de l’Ordre national du Québec, Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur, Chevalier de l’Ordre de Pie IX, Chevalier de l’ordre de la Pléade, Chevalier de l’ordre de la Palme académique are all authentic titles, but none of them confer nobility. Various types of societies also use the designation of chevalier as do the Chevaliers de Colomb (Knights of Columbus). Therefore if someone is addressed as chevalier, it rarely means descent from nobility. Again, caution is in order!

If your ancestor was an officer in the French army or navy at the time of New France, chances are very good that he was armigerous, since most officers were drawn from the nobility. But this should only serve as a guideline since there are exceptions to this general rule. A case in point is Charles Daniel who was a sea captain (a senior officer) in New France, long before the king ennobled him in 1648. Had he not been ennobled or deceased before being ennobled, he would not normally have been entitled to granted arms although he had served for many years as an officer. The same is true of Joseph-François de la Fresnière who, although made a lieutenant in 1696 and a captain in 1712, only received letters of nobility and a proper grant of arms in 1716. [14]

During the period of New France, the king ennobled eleven worthy Canadians and some noble families settled in the colony. But nobles were a very small percentage of the population, in fact about 100 families in 1767. [15] If you can prove that you are descended from one of these nobles and can identify their coat of arms, you certainly have an historic claim to the arms. France today is a republic and does not give official recognition to arms. But if you are a Canadian descended from a French armigerous ancestor, the Chief Herald of Canada would be able to grant you the old arms with adequate marks of difference added to make them specific to yourself.

There is no doubt that there are other families of French origin whose ancestors made use of bourgeois arms, but they are not numerous in Canada. [16] In fact such claims are most difficult to prove. French sources frequently state that a family in a particular area bore such and such arms and this is really too vague to constitute a proof of entitlement for a person living today. Indeed, proof may be almost impossible in the case of the arms of commoners, particularly if they precede1696 when such arms began to be registered. But anyone who seriously and with scientific rigor searches for ancestral arms through genealogy and historical documentation cannot be faulted, even if the search should prove inconclusive. In many cases, heraldic authorities will grant elements of the arms traditionally used by families in a specific area of a country if the ancestors of the petitioner originate from that area.

Assumed Arms

In some cases, persons will design their own original arms or have them designed by an amateur heraldist. That approach is not illegal and is more honest than taking someone else’s arms from a published work based only on a family name.

On the other hand, such arms do not necessarily respect some of the fundamental rules of heraldry and are sometimes drawn contrary to its aesthetics. If such arms begin appearing on bookplates, rings and other family heirlooms, descendants are easily convinced that they are true authentic emblems. Over time one of the descendants is bound to discover, with some disappointment, that the arms used for many years or by several generations by his family have no official status and cannot be made official in the form in which they were designed.

It takes years of study and practice to become a competent lawyer, engineer or doctor. Similarly it takes many years of study and practice to become competent in heraldry. While heralds should possess a good knowledge of history, mythology and a broad general culture allowing them to design beautiful and significant heraldry, they do not necessarily have any artistic talent. They usually have to call upon an artist able to depict coats of arms with the beauty they warrant. Conversely artists may not possess the historical knowledge required to create significant arms. Only a few persons can do both. That is why heraldic authorities work as a team of highly skilled specialists. From this point of view, it is pretentious for an individual to think of creating good heraldry overnight or that a friend with artistic ability will put a design into proper form. Even a person highly skilled in drawing and painting requires a period of study and practice to become a successful heraldic artist.

Grants by Metropolitan Authorities

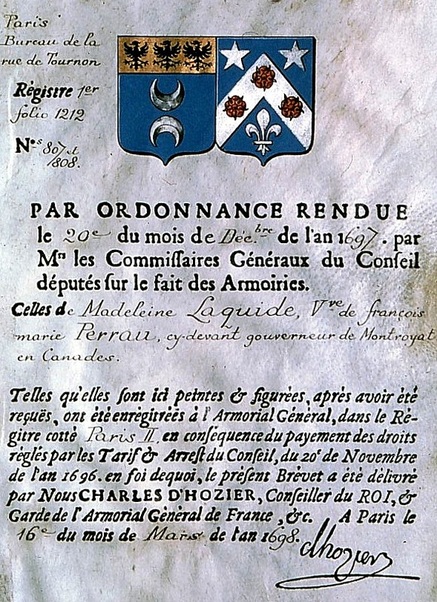

At the time of New France, nobles who settled in Canada brought their own arms with them, but grants of arms to persons living in Canada were very few. We know that, of the eleven Canadians ennobled by the sovereign, at least ten had arms. The edict of 1696 did not apply to New France, but possibly a few Canadians were in France at the time the edict was in force and obtained arms via that route (fig. 16). After Canada had been conquered in 1759, at least one Canadian had armorial dealings with France. In 1761 Pierre Raimbault de Simblim obtained arms from the judge of arms Louis-Pierre d’Hozier for his father Paul, a seigneur but apparently not a noble. In 1787 Michel Chartier de Lotbinière had his ancestral arms modified by the Judge of Arms Antoine-Marie d’Hozier de Sérigny. [17] An estimate of the total French grants to Canadians would be about a dozen, possibly a little more.

Fig. 16 Certificate issued 16 March 1698 by Charles d’Hozier, garde de l’Armorial général de France, on behalf of Madeleine Meynier Laguide, widow of François-Marie Perrau (Perrot), governor of Montréal (1669-1684) and of Acadia (1684-1687), died in Paris in 1691. Document in the Archives nationales du Québec, photographed by the National Archives of Canada in 1977.

Prior to the establishment of the Canadian Heraldic Authority in 1988, the Heralds of England and the Court of the Lord Lyon in Scotland made a number of grants in favour of Canadians. An early confirmation of arms by the British Heralds dated 29 September 1760 was to Thomas Ainslie, a Scottish collector of customs at Quebec. A second person to seek the services of the College of Arms was the military engineer Gaspard-Joseph Chaussegros de Léry. Having been wounded during the battle of the Plains of Abraham, he was sent to France with his family in 1761. When he failed to receive an interesting appointment from the French government, he went to England and there had his genealogy, the arms of his father as well as the Cross of Saint-Louis―whom several members of his family had received―registered by Somerset and Lancaster Heralds in a document dated 1st June 1763. [18] He was the first Canadian seigneur to be presented to an English sovereign, namely George III. Another early grant was in 1778 by the Lyon King of Arms in favour of James Cuthbert, seigneur of Berthier. [19]

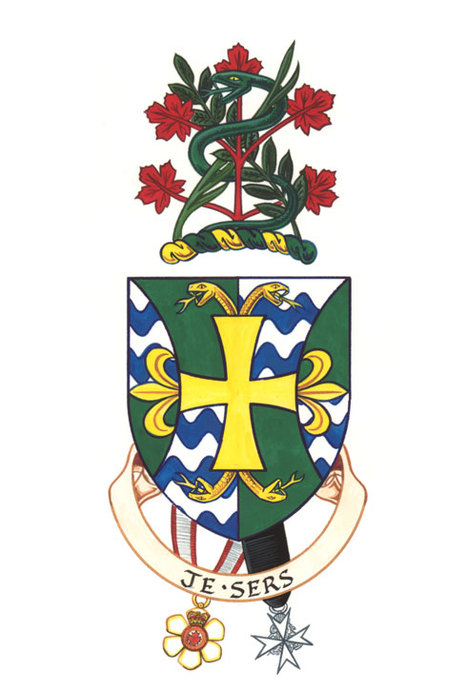

Such grants became more numerous in the 19th and 20th centuries and the descendants of these grantees are entitled to arms, but the claim should be based on a copy of the granting document and proof of descent from the grantee or confirmation by the College of Arms, Court of the Lord Lyon or Chief Herald of Ireland where the arms were granted originally (figs. 17-19).

Such grants became more numerous in the 19th and 20th centuries and the descendants of these grantees are entitled to arms, but the claim should be based on a copy of the granting document and proof of descent from the grantee or confirmation by the College of Arms, Court of the Lord Lyon or Chief Herald of Ireland where the arms were granted originally (figs. 17-19).

Fig. 17 The arms of Gustave Gingras of Monticello, Prince Edward Island, recorded by the College of Arms, London, England, 18 June 1974, registered at the Canadian Heraldic Authority, 22 December 1993, vol. II, p. 300: http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1719&ProjectElementID=5780. The insignia of a Companion of the Order of Canada and of a Knight of Justice of the Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem are appended below his shield. Reproduced by permission of the Canadian Heraldic Authority of Canada © Her Majesty in Right of Canada. For further information on the College of arms see: http://www.college-of-arms.gov.uk/services/granting-arms.

Fig. 18 The arms of John Ross Matheson of Rideau Ferry, Ontario, recorded at the Court of the Lord Lyon, Edinburgh, Scotland, 14 September 1959, registered at the Canadian Heraldic Authority, March 20, 1990, vol. II, p. 17: http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1420&ShowAll=1 and http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1421. Reproduced by permission of the Canadian Heraldic Authority of Canada © Her Majesty in Right of Canada. For further information on the Court of the Lord Lyon see: http://www.lyon-court.com/lordlyon/228.html.

Fig. 19 The arms of John Redmond Roche of Montréal, Quebec, recorded at the Office of the Chief Herald of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland, 1 June 1962, recorded at the College of Arms, 10 October 1967, registered at the Canadian Heraldic Authority, 20 May 1992,vol. II, p. 162: http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=1578 and http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project-pic.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=501&ProjectElementID=1685. The insignia (from left to right) of an Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, of a Member of the Order of Canada and of a Knight of Justice of the Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem are appended below his shield. The motto alludes to the name of the armiger as do the fish (roach). Reproduced by permission of the Canadian Heraldic Authority of Canada © Her Majesty in Right of Canada. For further information on the Chief Herald of Ireland, see: http://www.nli.ie/en/applying-for-a-grant-of-arms.aspx, which has a section entitled “recently granted Grants of Arms” where the format of letters of arms can be viewed.

The Canadian Heraldic Authority

The prerogative in matters of official heraldry in Canada has always belonged to the Crown. It was the prerogative of French monarchs until 1763 and of British sovereigns afterwards. On 4 June 1988, the exercise of the royal prerogative in all heraldic matters was transferred to the Governor General of Canada by virtue of a Royal Proclamation of Queen Elizabeth II as Queen of Canada, a title bestowed upon her by the Canadian Parliament in 1953. Though empowered to grant armorial bearings in Canada, the governor general has delegated most of the granting authority to the Chief Herald of Canada, appointed by commission and assisted by a Deputy Chief Herald and several heralds.

The title of Chief Herald of Canada sounds like that of Chief Herald of Ireland, although Ireland is a republic and Canada a constitutional monarchy. Despite this political status, Canada sometimes finds it advantageous to navigate between monarchical and republican attitudes. It is well known that the Fathers of Confederation had opted for Kingdom of Canada as a name for the newly formed country, but the British government urged them to find another title for fear of antagonizing the United States. [20] At that time, just after the Civil War, the Americans could have mustered formidable forces against their northern neighbour. Similarly, while the title of King of Arms of Canada would have delighted some Canadians, it would surely have raised eyebrows in other quarters.

For administrative purposes, the Chief Herald is responsible to the Deputy Herald Chancellor who in turn reports to the Herald Chancellor who is also Secretary to the Governor General. In England, Norroy holds the office of king of arms of the northern province (north of the River Trent) and Clarenceux is king in the south. In Canada, heralds are named after rivers such as the St. Lawrence, Athabaska, Fraser, Saguenay, Assiniboine, Miramichi and Coppermine rivers and have no assigned territorial jurisdiction. Besides the permanent heralds, there are a number of heralds who acted as consultants in various regions and who were later appointed Heralds Extraordinary under the names of Dauphin, Niagara, Cowichan, Albion, Capilano and Rouge. Independent artists, duly accredited by the Canadian Heraldic Authority and supervised by Fraser Herald, do the artwork and calligraphy. Two heralds have received the honorary title of emeritus upon retirement: Outaouais (Auguste Vachon, 2000, formerly Saint-Laurent), Rideau (Robert D. Watt, 2007, formerly Chief Herald of Canada).

Since most municipalities, corporate bodies, institutions, First Nations and individuals in Canada did not possess duly granted arms, the Canadian Heraldic Authority was brought into existence in 1988 to fill this void. The authority was empowered by royal proclamation to grant arms in the name of the Canadian Crown, as an expression of national sovereignty (figs 20-21). Since 1988 the Chief Herald of Canada has granted thousands of arms to municipalities, institutions, corporations and individuals. The governor general grants directly in special circumstances such as augmentations (additions) to the arms of provinces, the arms of his successor and the badges of heralds and special honours such as supporters granted to heralds emeritus. The Chief Herald of Canada grants most arms including those of the Herald Chancellor, Deputy Herald Chancellor and the lieutenant governors. In England grants of armorial bearings are issued under the individual seals of kings of arms. In Canada they are impressed with the seal of the Canadian Heraldic Authority or with the privy seal of the governor general in the special cases just mentioned. Contrary to English practice, none of the officers of arms of the Canadian Heraldic Authority have a seal of office.

The services provided by the Canadian Heraldic Authority can be summarized as follows:

1) diffuse information regarding its creation, mandate and structure;

2) make available a detailed procedure guide outlining the various steps required to petition for a grant of arms, the time required, the costs and the options available; [21]

3) receive petitions for grants of arms and work with the petitioner to arrive at a suitable design for specific arms;

4) prepare the Letters Patent by which the arms are granted;

5) answer any question relating to grants after they are completed;

6) provide information on correct heraldic practices;

7) offer general guidance on a number of heraldic matters, for instance the interpretation of a heraldic description.

The prerogative in matters of official heraldry in Canada has always belonged to the Crown. It was the prerogative of French monarchs until 1763 and of British sovereigns afterwards. On 4 June 1988, the exercise of the royal prerogative in all heraldic matters was transferred to the Governor General of Canada by virtue of a Royal Proclamation of Queen Elizabeth II as Queen of Canada, a title bestowed upon her by the Canadian Parliament in 1953. Though empowered to grant armorial bearings in Canada, the governor general has delegated most of the granting authority to the Chief Herald of Canada, appointed by commission and assisted by a Deputy Chief Herald and several heralds.

The title of Chief Herald of Canada sounds like that of Chief Herald of Ireland, although Ireland is a republic and Canada a constitutional monarchy. Despite this political status, Canada sometimes finds it advantageous to navigate between monarchical and republican attitudes. It is well known that the Fathers of Confederation had opted for Kingdom of Canada as a name for the newly formed country, but the British government urged them to find another title for fear of antagonizing the United States. [20] At that time, just after the Civil War, the Americans could have mustered formidable forces against their northern neighbour. Similarly, while the title of King of Arms of Canada would have delighted some Canadians, it would surely have raised eyebrows in other quarters.

For administrative purposes, the Chief Herald is responsible to the Deputy Herald Chancellor who in turn reports to the Herald Chancellor who is also Secretary to the Governor General. In England, Norroy holds the office of king of arms of the northern province (north of the River Trent) and Clarenceux is king in the south. In Canada, heralds are named after rivers such as the St. Lawrence, Athabaska, Fraser, Saguenay, Assiniboine, Miramichi and Coppermine rivers and have no assigned territorial jurisdiction. Besides the permanent heralds, there are a number of heralds who acted as consultants in various regions and who were later appointed Heralds Extraordinary under the names of Dauphin, Niagara, Cowichan, Albion, Capilano and Rouge. Independent artists, duly accredited by the Canadian Heraldic Authority and supervised by Fraser Herald, do the artwork and calligraphy. Two heralds have received the honorary title of emeritus upon retirement: Outaouais (Auguste Vachon, 2000, formerly Saint-Laurent), Rideau (Robert D. Watt, 2007, formerly Chief Herald of Canada).

Since most municipalities, corporate bodies, institutions, First Nations and individuals in Canada did not possess duly granted arms, the Canadian Heraldic Authority was brought into existence in 1988 to fill this void. The authority was empowered by royal proclamation to grant arms in the name of the Canadian Crown, as an expression of national sovereignty (figs 20-21). Since 1988 the Chief Herald of Canada has granted thousands of arms to municipalities, institutions, corporations and individuals. The governor general grants directly in special circumstances such as augmentations (additions) to the arms of provinces, the arms of his successor and the badges of heralds and special honours such as supporters granted to heralds emeritus. The Chief Herald of Canada grants most arms including those of the Herald Chancellor, Deputy Herald Chancellor and the lieutenant governors. In England grants of armorial bearings are issued under the individual seals of kings of arms. In Canada they are impressed with the seal of the Canadian Heraldic Authority or with the privy seal of the governor general in the special cases just mentioned. Contrary to English practice, none of the officers of arms of the Canadian Heraldic Authority have a seal of office.

The services provided by the Canadian Heraldic Authority can be summarized as follows:

1) diffuse information regarding its creation, mandate and structure;

2) make available a detailed procedure guide outlining the various steps required to petition for a grant of arms, the time required, the costs and the options available; [21]

3) receive petitions for grants of arms and work with the petitioner to arrive at a suitable design for specific arms;

4) prepare the Letters Patent by which the arms are granted;

5) answer any question relating to grants after they are completed;

6) provide information on correct heraldic practices;

7) offer general guidance on a number of heraldic matters, for instance the interpretation of a heraldic description.

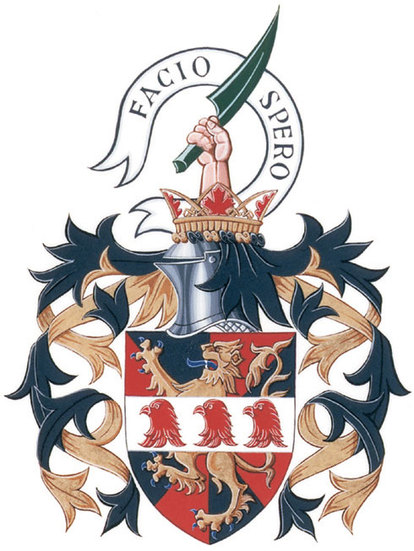

Fig. 20 Grant of arms, a badge, a banner and a standard to John Gerard Dunlap, Q.C., and differenced arms to his children John Timothy Andrew and Joanne Elizabeth, by the Chief Herald of Canada, 15 July 2003. Reproduced by permission of the Canadian Heraldic Authority of Canada © Her Majesty in Right of Canada. See: http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=98&ShowAll=1 and http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=2121&ShowAll=1.

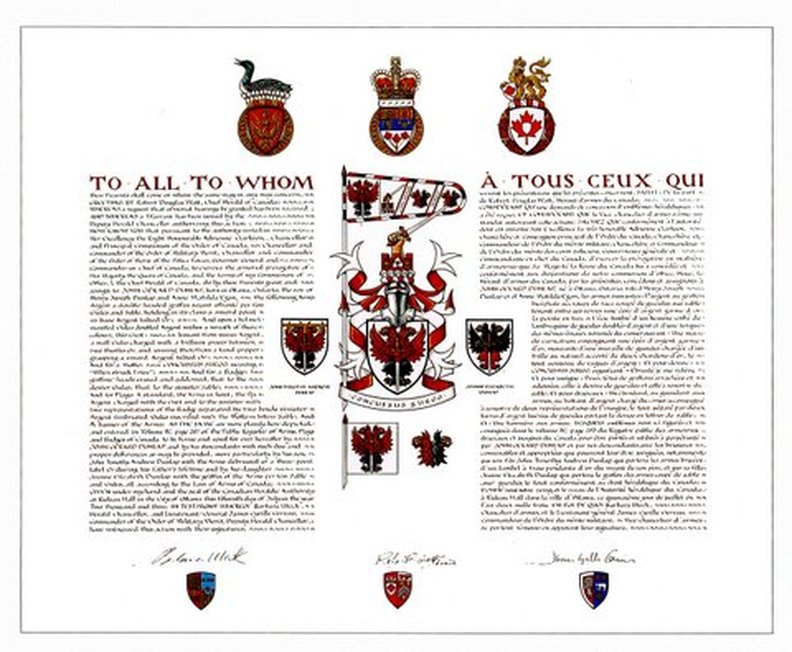

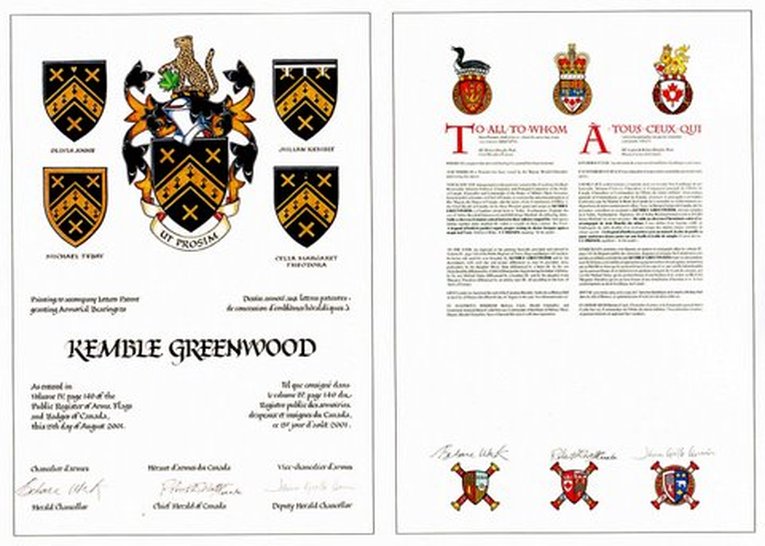

Fig. 21 Grant of arms to Kemble Greenwood and differenced arms to his four children Olivia Anne, Julian Kemble, Michael Tebay and Celia Margaret Theodora, by the Chief Herald of Canada, 15 August 2001. Two part document. Reproduced by permission of the Canadian Heraldic Authority of Canada © Her Majesty in Right of Canada. See: http://reg.gg.ca/heraldry/pub-reg/project.asp?lang=e&ProjectID=240&ShowAll=1.

Because requests for grants are so numerous, heralds do not have time to research the possible existence of ancestral arms for a particular family. Its role is to design arms in cooperation with petitioners and to prepare the required documents for official grants to Canadian citizens and corporate bodies. Sometimes the Canadian Heraldic Authority has sent information on arms found in various works under a family name, but cautioning that one had to prove descent from the original armiger to be entitled to the arms in question. But even doing this basic research takes considerable time. Ideally the Canadian Heraldic Authority should only respond to petitions for a grant of official arms and answer questions that relate specifically to these petitions and to the arms it has granted.

While requests to identify arms on objects such as silver or china or to identify flags are legitimate, they can be time consuming. Answering such inquiries is not the Canadian Heraldic Authority’s primary mandate and spending research time for this purpose is unfair to petitioners who pay some of the costs of having arms granted by the Canadian Crown. The reader can learn how to do this type of research by reading chapter VI and appendix III and putting in the required time.

No one would normally expect library staff to draw up their genealogy and yet, although a similar amount of work is required to successfully prove entitlement to ancestral arms, inquirers call the Canadian Heraldic Authority expecting heralds to produce their arms in the twinkling of an eye. This is explained by the belief that heralds only have to find family arms under a name in a book or by searching a computerized data bank. While the herald may find arms under a family name as vendors do, the chances that they belong to the specific family line of the inquirer are extremely remote. In fact the unlawful usurpation of another person’s arms, should it become known by the rightful owner, could lead to legal prosecution in some countries.

In a nutshell, the Canadian Heraldic Authority should not be expected to:

1) perform extensive genealogical research relating to ancestral arms;

2) proclaim as being authentic arms found under the one’s family name in books or other general sources;

3) allow the use of arms it has granted to a specific person and descendants by someone else who has the same family name but is not descended from the person to whom the arms were granted.